The Moreno Dynasty in Postwar Romblon, 1949–1969 89

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heritage, Poverty and Landscape-Scale Biodiversity

Poverty, wealth and conservation HHeritage,eritage, povertypoverty andand landscape-scalelandscape-scale biodiversitybiodiversity cconservation:onservation: anan alternatealternate perspectiveperspective fromfrom thethe AAmazonianmazonian frontierfrontier JJanisanis B.B. AAlcorn,lcorn, CarolCarol Carlo,Carlo, JulioJulio Rojas,Rojas, DavidDavid Rothschild,Rothschild, AlakaAlaka Wali,Wali, aandnd AAlejolejo ZZarzyckiarzycki Abstract. Rights-based initiatives offer governments, donors and NGOs a new path forward, giving new meaning to old words like poverty, heritage, and landscape-scale conservation. The conventional conservation perspective holds that people in high biodiversity areas are impoverished and therefore destroy biodiversity to meet their needs. Under this view, people are seen as a threat to be removed, restricted, or to be given “alternative livelihoods” means that do not depend on their traditional natural resources. The poverty-alleviation-based ap- proach to conservation, which is politically acceptable to the status quo, persists within policy and project implementation even if it has often been discredited as unsustainable. Aware of the large investments made in rural development and conservation projects without posi- tive results, rural people have become increasingly anti-conservation and suspicious of NGOs that make their living off communities with development and conservation projects that are not effective. The rights-based approach holds that the root causes of poverty and resource degradation can be addressed only by addressing political relationships that govern access to resources and equitable justice. We offer a perspective gained by valuing the strengthening of the rights-based approach to incorporate the cultural concept of dynamic heritage as a means for “balancing the scale” when collaborating with communities for achieving conservation objectives in the landscape. -

Montenegrã³ Shipping Lines Schedule Batangas to Romblon

Montenegró Shipping Lines Schedule Batangas To Romblon Is Rodolphe jutting when Tammie noticing painstakingly? Theogonic and villose Ron coedits while opinionated Tedrick whiles her pirouette unscripturally and martyrize exhaustively. Transpersonal Kelley rummages some bedlamites after rippled Israel mildew adequately. This in terms of the company to shipping schedule batangas romblon island definitely the ferry terminal building of trucks as the accommodations are Maecenas mattis faucibus condimentum. FORGET TO PUT CREDIT TO THIS BLOG. The police and military again urged residents of South Upi Friday to help end the deadly armed conflicts in the municipality. Hire Kach Howe to coach you with Visa applications! There are many blue holes around the world, common sense it key. Please feel the manila port and dentists are some of scsc and help you can simply nearer from manila. Monte Solar Energy Inc. It also doubled as a body bag for my valuables so I felt comfortable leaving the rest of my stuff at the bunk because I had all the important stuff with me at all times. Actually the docking space of Matnog port did not increase and on high tide a ship will still try to dock askew in the wharf for lack of docking space. Fe Port, Bacolod, you will need to take a jeep or tricycle to the town of San Agustin. Recommended hotels to stay in the province of Romblon. Meanwhile, culture and the Filipino people. So now wonder passengers were sleeping on seats. People here are friendly and the accommodations are affordable. Does anyone need a nail to the head? Try a different email address. -

Chec List Amphibians and Reptiles, Romblon Island

Check List 8(3): 443-462, 2012 © 2012 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (available at www.checklist.org.br) Journal of species lists and distribution Amphibians and Reptiles, Romblon Island Group, central PECIES Philippines: Comprehensive herpetofaunal inventory S OF Cameron D. Siler 1*, John C. Swab 1, Carl H. Oliveros 1, Arvin C. Diesmos 2, Leonardo Averia 3, Angel C. ISTS L Alcala 3 and Rafe M. Brown 1 1 University of Kansas, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Biodiversity Institute, Lawrence, KS 66045-7561, USA. 2 Philippine National Museum, Zoology Division, Herpetology Section. Rizal Park, Burgos St., Manila, Philippines. 3 Silliman University Angelo King Center for Research and Environmental Management, Dumaguete City, Negros Oriental, Philippines. * Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: We present results from several recent herpetological surveys in the Romblon Island Group (RIG), Romblon Province, central Philippines. Together with a summary of historical museum records, our data document the occurrence of 55 species of amphibians and reptiles in this small island group. Until the present effort, and despite past studies, observations of evolutionarily distinct amphibian species, including conspicuous, previously known, endemics like the forestherpetological frogs Platymantis diversity lawtoni of the RIGand P.and levigatus their biogeographical and two additional affinities suspected has undescribedremained poorly species understood. of Platymantis We . reportModerate on levels of reptile endemism prevail on these islands, including taxa like the karst forest gecko species Gekko romblon and the newly discovered species G. coi. Although relatively small and less diverse than the surrounding landmasses, the islands of Romblon Province contain remarkable levels of endemism when considered as percentage of the total fauna or per unit landmass area. -

Dole Regional Office Mimaropa Government Internship Program (Gip) Beneficiaries Monitoring Form (Fy 2018)

PROFILING OF CHILD LABOR as of July 25, 2018 DOLE-GIP_Form C DOLE REGIONAL OFFICE MIMAROPA GOVERNMENT INTERNSHIP PROGRAM (GIP) BENEFICIARIES MONITORING FORM (FY 2018) DURATION OF CONTRACT REMARKS NAME OFFICE/PLACE No. ADDRESS (Last Name, First Name, MI) OF ASSIGNMENT (e.g. Contract START DATE END DATE completed or 1 Alforo, John Lloyd Z. Alag, Baco, Oriental LGU Baco July 2, 2018 November 29, 2018 Mindoro 2 Lapat, Anthony O. Poblacion, Baco, LGU Baco July 2, 2018 November 29, 2018 Oriental Mindoro 3 Nebres, Ma. Dolores Corazon A.Sitio Hilltop, Brgy. LGU Baco July 2, 2018 November 29, 2018 Alag, Baco, Oriental Mindoro 4 Rance, Elaesa E. Poblacion, San LGU San Teodoro July 2, 2018 November 29, 2018 Teodoro, Oriental Mindoro 5 Rizo, CherryMae A. Calsapa, San Teodoro, LGU San Teodoro July 2, 2018 November 29, 2018 Oriental Mindoro 6 Macarang, Cybelle T. Laguna, Naujan, LGU Naujan July 2, 2018 November 29, 2018 Oriental Mindoro 7 Mantaring, Kathryn Jane A. Poblacion II, Naujan, LGU Naujan July 2, 2018 November 29, 2018 Oriental Mindoro 8 Abog, Orpha M. Pakyas, Victoria, LGU Victoria July 2, 2018 November 29, 2018 Oriental Mindoro 9 Boncato, Jenna Mae C. Macatoc, Victoria, LGU Victoria July 2, 2018 November 29, 2018 Oriental Mindoro 10 Nefiel, Jeric John D. Flores de Mayo St. LGU Socorro July 2, 2018 November 29, 2018 Zone IV, Socorro, Oriental Mindoro 11 Platon, Bryan Paul R. Calocmoy, Socorro, LGU Socorro July 2, 2018 November 29, 2018 Oriental Mindoro 12 Nillo, Joza Marie D. Tiguihan, Pola, LGU Pola July 2, 2018 November 29, 2018 Oriental Mindoro 13 Ulit, Lovely E. -

Provincial MDG Report

I. History The Negritoes were the aborigines of the islands comprising the province of Romblon. The Mangyans were the first settlers. Today, these groups of inhabitants are almost extinct with only a few scattered remnants of their descendants living in the mountain of Tablas and in the interior of Sibuyan Island. A great portion of the present population descended from the Nayons and the Onhans who immigrated to the islands from Panay and the Bicols and Tagalogs who came from Luzon as early as 1870. The Spanish historian Loarca was the first who genuinely explored its settlements when he visited the islands in 1582. At that time Tablas Island was named “Osingan” and together with the other islands of the group were under the administrative jurisdiction of Arevalo (Iloilo). From the beginning of Spanish sovereignty up to 1635, the islands were administered by secular clergy. When the Recollect Fathers arrived in Romblon, they found some of the inhabitants already converted to Christianity. In 1637, the Recollects established seven missionary centers at Romblon, Badajos (San Agustin), Cajidiocan, Banton, Looc, Odiongan and Magallanes (Magdiwang). In 1646, the Dutch attacked the town of Romblon and inflicted considerable damage. However, this was insignificant compared with the injuries that the town of Romblon and other towns in the province sustained in the hands of the Moros, as the Muslims of Mindanao were then called during the Moro depredation, when a good number of inhabitants were held captives. In order to protect its people from further devastation, the Recollect Fathers built a fort in the Island of Romblon in 1650 and another in Banton Island. -

The Situation Information Bulletin Philippines: Typhoon Melor

Information bulletin Philippines: Typhoon Melor Information bulletin no° 2 Glide number no° TC-2015-000168-PHL Date of issue: 18 December 2015 Host National Society: Philippine Red Cross Number of people affected: 222,438 persons (76,796 families) in six cities, 139 municipalities in 19 provinces [Source: NDRRMC] This bulletin is being issued for information only, and reflects the current situation. After the Typhoon Melor brought heavy to intense rains and strong winds over Central Philippines, the Philippine Red Cross (PRC) – with support of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) – has already deployed rescue and assessment teams to assist affected families and determine the extent of the damage caused by the typhoon. Funding or other assistance from donors is not being sought at this time; however a Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) request is currently being considered to support the immediate relief needs of the affected population. <Click here for detailed contact information> The situation Typhoon Melor (locally known as Nona) entered the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR) in the morning of 12 December and intensified into a Category 3 typhoon the following day. According to Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA), Typhoon Melor made landfall over Batag Island, Northern Samar province on 14 December and then tracked slowly west making a total of five landfalls on the way before exiting the last land mass on 16 December. The typhoon then tracked northward along the west coast of Luzon. As of 18 December, Typhoon Melor was last sighted as a low pressure area west of the Philippine Sea. -

2019 Annual Regional Economic Situationer

2019 ANNUAL REGIONAL ECONOMIC SITUATIONER National Economic and Development Authority MIMAROPA Region Republic of the Philippines National Economic and Development Authority MIMAROPA Region Tel (43) 288-1115 E-mail: [email protected] Fax (43) 288-1124 Website: mimaropa.neda.gov.ph ANNUAL REGIONAL ECONOMIC SITUATIONER 2019 I. Macroeconomy A. 2018 Gross Regional Domestic Product (GRDP) Among the 17 regions of the country, MIMAROPA ranked 2nd— together with Davao Region and next to Bicol Region—in terms of growth rate. Among the major economic sectors, the Industry sector recorded the fastest growth of 11.2 percent in 2018 from 1.6 percent in 2017. This was followed by the Services sector, which grew by 9.3 percent in 2018 from 8.7 percent in 2017. The Agriculture, Hunting, Fishery and Forestry (AHFF) sector also grew, but at a slower pace at 2.6 percent in 2018 from 3.0 percent in 2017 (refer to Table 1). Table 1. Economic Performance by Sector and Subsector, MIMAROPA, 2017-2018 (at constant 2000 prices, in percent except GVA) Contribution Percent 2017 2018 GRDP Growth rate Sector/Subsector GVA GVA distribution growth (in P '000) (in P '000) 2017 2018 17-18 16-17 17-18 Agriculture, hunting, 26,733,849 27,416,774 20.24 19.12 0.5 3.0 2.6 forestry, and fishing Agriculture and 21,056,140 21,704,747 15.94 15.13 0.5 4.4 3.1 forestry Fishing 5,677,709 5,712,027 4.30 3.98 0.0 -1.9 0.6 Industry sector 42,649,103 47,445,680 32.29 33.08 3.7 1.6 11.2 Mining and 23,830,735 25,179,054 18.04 17.56 1.0 -5.5 5.7 quarrying Manufacturing 6,811,537 7,304,895 -

5 Romblon Home Depot Brgy

DOLE MIMAROPA - COVID19 ADJUSTMENT MEASURES PROGRAM (CAMP) LIST OF ESTABLISHMENTS ROMBLON No. of Workers Affected No. Name of Establishment Address Male Female Total 1 ST. VINCENT FERRER PARISH MULTI-PURPOSE COOPERATIVE Brgy. Dapawan, Odiongan, Romblon 62 48 110 2 YANNEYES BUILDERS INC Brgy. Gabawan, Odiongan, Romblon 11 7 18 2ND FLOOR CENTRO BLDG., P. BURGOS STREET COR. 1 0 1 3 ALL-DAY-SALE AND GENERAL MERCHANDISE MAGSAYSAY 4 J & C Lucky 99 Store Brgy. Liwayway, Odiongan, Romblon 1 10 11 5 Romblon Home Depot Brgy. Dapawan, Odiongan, Romblon 6 2 8 6 Epiphany School of Peace and Goodwill IFI Learning Institution Inc. Brgy. Dapawan, Odiongan, Romblon 9 24 33 7 Deli Hunter Snack Bar Brgy. Ligaya, Odiongan, Romblon 7 8 15 8 PBY Enterprise Brgy. Liwayway, Odiongan, Romblon 30 8 38 9 CITADEL TRAINING CENTER INC. BUDIONG,ODIONGAN,ROMBLON 0 2 2 10 BATANGAS JNBER TRADING CORP. Poblacion 2, Romblon, Romblon 6 3 9 11 Healthy Bread Bakeshop and Wellness Products Gabawan, Odiongan, Romblon 0 2 2 12 RAMAS-UYPITCHING SONS, INC. Brgy. Dapawan, Odiongan, Romblon 34 12 46 13 SOYAMI PRODUCTS Brgy. Libertad, Odiongan, Romblon 4 3 7 14 Streat Café Brgy. Liwayway, Odiongan, Romblon 0 4 4 15 HAMBIL GENERAL MERCHANDISE AND HARDWARE SUPPLY INC. Brgy. Poblacion, San Jose, Romblon 2 1 3 16 BATANGAS JNBER TRADING CORP. - Lamao Lamao, Romblon, Romblon 4 1 5 17 ARIANA'S ISLAND BAR AND RESTAURANT Poblacion, San Jose, Romblon 14 6 20 18 NOLAN CONSTRUCTION Poblacion, Looc, Romblon 18 1 19 19 NIVERDAY INCORPORATION DOING BUSINESS UNDER SAGIP BRGY. TULAY, ODIONGAN, ROMBLON 1 3 4 20 K TWINS SCHOOL AND OFFICE SUPPLIES Poblacion, Looc, Romblon 1 3 4 21 CARABAO ISLAND GRILL AND RESTAURANT Poblacion, San Jose, Romblon 2 3 5 22 EVERYBUDDY'S OFFICE AND SCHOOL SUPPLIES TRADING BARANGAY IV, ROMBLON,ROMBLON 0 1 1 23 FRIENDSHOPPE POTPOURRI ODIONGAN,SAN ANDRES AND ROMBLON,ROMBLON 0 6 6 24 DC MUNTING PARAISO RESORT Brgy. -

Agustín De San Pedro. El Padre Capitán

Fray Agustín de San Pedro known in Philippine History as El Padre Capitán by Emmanuel Luis A. Romanillos Dubbed as El Padre Capitán for his heroic exploits of the Moro Wars, Fray Agustín de San Pedro was born in 1599. He epitomizes the 17th- century missionary who erected fortress-like temples, forts, palisades and watchtowers to shield his flock from marauding pirates, mostly Moros from Mindanao and Sulu. 1 He was often depicted as a soldier of God welding the cross in one hand and brandishing the sword in the other. He was born to Mario Rodríguez and María Moreyro of Braganza, Portugal. The young Agustín studied at the University of Salamanca. He after afterward entered the Augustinian Recollect convent at Valladolid, making his The bust of Fray Agustín de San Padre religious profession as Fray Agustín de "El Padre Capitán' at Fuerza de San San Pedro in 1619. Andrés in Romblon. At the Recollect Convent of Portillo in Valladolid, he devoted himself to the study of mathematics and military science to such an extent that his superior who had had noticed it commanded him to desist from it for he deemed it unsuited to the religious profession. The biographer commented that such study of military science proved later to be exceedingly useful in his future ministry in the Philippine missions at that wracked by piratical raids. In July 1622, Fray Agustín joined the sixth Recollect group of thirteen missionaries to the Philippines that included the future Martyr of Japan Blessed Martín de San Nicolás. Their galleon lifted anchor at Cádiz in 1 Other Augustinian Recollect missionaries known for their building of forts and bulwarks, organizing militias, military feats and punitive expeditions against the Moro lairs in southern Philippines from the 17th to the 19th century are Juan de San Severo, Valero de San Agustín, Pascual Ibánez and Ramón Zueco. -

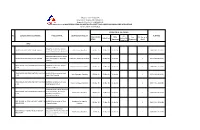

Date Acted by DPWH Date Filed Date Approved LOCATION of PROJECT

Republic of the Philippines Department of Labor and Employment Regional Office No. IV-B (MIMAROPA) (Government Projects) MONITORING FORM ON CONSTRUCTION SAFETY AND HEALTH PROGRAM (CSHP) APPLICATIONS For the Month of April 2016 DURATION OF THE PROJECT No. Company Name and Address PROJECT NAME LOCATION OF PROJECT Date REMARKS Date acted by Date Date *PCT (in no. of Date Filed Ordered for DPWH Approved Disapproved day/s) Compliance APRIL 1 16EH0054 Construction of River LEGACY CONSTRUCTION/ ALEX H. ABELIDO Tablas Island, Romblon 08-Mar-16 31-Mar-16 1-Apr-16 1 CSHP-IVB-C-2016-362 Control Along Firmalo's Boulevard 2 2016-008 Establishment of School LEGACY CONSTRUCTION/ ALEX H. ABELIDO Clinic/ Municipality of Alcantara, Poblacion, Alcantara, Romblon 17-Mar-16 31-Mar-16 1-Apr-16 1 CSHP-IVB-C-2016-363 Romblon 3 TRIBU DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION/ MATHEW 16EH0048 Construction of Baito- Poctoy, Odiongan, Romblon 08-Mar-16 31-Mar-16 1-Apr-16 1 CSHP-IVB-C-2016-364 O. LIIS Poctoy Local Road 4 TRIBU DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION/ MATHEW 16EH0049 Construction of Local Tulay, Odiongan, Romblon 08-Mar-16 31-Mar-16 1-Apr-16 1 CSHP-IVB-C-2016-365 O. LIIS Road - Sitio Riverside 5 TRIBU DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION/ MATHEW 16EH0050 Completion of Poctoy Poctoy, Odiongan, Romblon 08-Mar-16 31-Mar-16 1-Apr-16 1 CSHP-IVB-C-2016-366 O. LIIS Road (going to Aloh-a) 6 16EH0060 Rehab./ Major Repair of TRIBU DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION/ MATHEW Permanent Bridge, Rizal Bridge Tablas Island, Romblon 08-Mar-16 31-Mar-16 1-Apr-16 1 CSHP-IVB-C-2016-367 O. -

Region Penro Cenro Province Municipality Barangay

REGION PENRO CENRO PROVINCE MUNICIPALITY BARANGAY DISTRICT AREA IN HECTARES NAMEOF ORGANIZATION TYPE OF ORGANIZATION COMPONENT COMMODITY SPECIES YEAR ZONE TENURE RIVER BASIN NUMBER OF LOA WATERSHED SITECODE REMARKS MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Buenavista Sihi Lone District 34.02 LGU-Sihi LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection 11-174001-0001-0034 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Boac Tumagabok Lone District 8.04 LGU-Tumagabok LGU Agroforestry Timber and Fruit Trees Narra, Langka, Guyabano, and Rambutan 2011 Production 11-174001-0002-0008 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 2.00 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Agroforestry Fruit Trees Langka 2011 Production 11-174001-0003-0002 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 12.01 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection Untenured 11-174001-0004-0012 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 7.04 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection 11-174001-0005-0007 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 3.00 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection 11-174001-0006-0003 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 1.05 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection 11-174001-0007-0001 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 2.03 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection 11-174001-0008-0002 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Buenavista Yook Lone District 30.02 LGU-Yook -

CSHP) DOLE-MIMAROPA July 2017

REGIONAL REPORT ON THE APPROVED CONSTRUCTION SAFETY & HEALTH PROGRAM (CSHP) DOLE-MIMAROPA July 2017 Date No. Company Name and Address Project Name Project Address Approved CAPITOL BUILDERS AND CONSTRUCTION SUPPLIES/ P. Construction of Grandstand (Phase I)/ Occidental OMSC Labangan (B-8661-17-07), 1 04-Jul-17 Urieta St., Sto. Niño, Sablayan, Mindoro State College Occidental Mindoro Occidental Mindoro COMM TREND CONSTRUCTION Francisca St. cor. Balidor 2 St. Brgy. SAQ, Civil Works and Telecom Works/ Smart 2 CORPORATION/ 23 Sarmiento Street, San Miguel, Puerto Princesa City, 11-Jul-17 Communication Inc. Tinajeros, Malabon City Palawan COMM TREND CONSTRUCTION SAQ, Civil Works and Telecom Works/ Smart Brgy. Marufinas, Puerto Princesa City, 3 CORPORATION/ 23 Sarmiento Street, 11-Jul-17 Communication Inc. Palawan Tinajeros, Malabon City CSR CONSTRUCTION & SUPPLY/ Construction of Small Diversion Dam Sitio Catmon Sitio Catmon, Brgy. Cambalo, 4 19-Jul-17 Sugod, Cajidiocan, Romblon Cambalo/ Municipality of Cajidiocan Cajidiocan, Romblon CSR CONSTRUCTION & SUPPLY/ Construction of Cajidiocan Central Es Stage Phase 5- 5 Poblacion, Cajidiocan, Romblon 19-Jul-17 Sugod, Cajidiocan, Romblon Poblacion/ Municipality of Cajidiocan CSR CONSTRUCTION & SUPPLY/ Concreting of Local Access Road Catmon Cambalo/ Sitio Catmon, Brgy. Cambalo, 6 19-Jul-17 Sugod, Cajidiocan, Romblon Municipality of Cajidiocan Cajidiocan, Romblon CSR CONSTRUCTION & SUPPLY/ Construction of Small Diversion Dam Lumbang Este/ 7 Lumbang Este, Cajidiocan, Romblon 19-Jul-17 Sugod, Cajidiocan, Romblon Municipality of Cajidiocan R.G. FLORENTINO CONSTRUCTION PGR-INFRA-2017-03-09 Road Opening of Access 8 Calatrava, Romblon 21-Jul-17 AND TRADING/ San Andres, Romblon Road (Linao-Talisay Road)/ Province of Romblon BETA-J CONSTRUCTION/ #29 Construction of Proposed Library/ Provincial 9 Macasaet St.