Chugach National Forest Alaska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steve Mccutcheon Collection, B1990.014

REFERENCE CODE: AkAMH REPOSITORY NAME: Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center Bob and Evangeline Atwood Alaska Resource Center 625 C Street Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: 907-929-9235 Fax: 907-929-9233 Email: [email protected] Guide prepared by: Sara Piasecki, Archivist TITLE: Steve McCutcheon Collection COLLECTION NUMBER: B1990.014 OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Dates: circa 1890-1990 Extent: approximately 180 linear feet Language and Scripts: The collection is in English. Name of creator(s): Steve McCutcheon, P.S. Hunt, Sydney Laurence, Lomen Brothers, Don C. Knudsen, Dolores Roguszka, Phyllis Mithassel, Alyeska Pipeline Services Co., Frank Flavin, Jim Cacia, Randy Smith, Don Horter Administrative/Biographical History: Stephen Douglas McCutcheon was born in the small town of Cordova, AK, in 1911, just three years after the first city lots were sold at auction. In 1915, the family relocated to Anchorage, which was then just a tent city thrown up to house workers on the Alaska Railroad. McCutcheon began taking photographs as a young boy, but it wasn’t until he found himself in the small town of Curry, AK, working as a night roundhouse foreman for the railroad that he set out to teach himself the art and science of photography. As a Deputy U.S. Marshall in Valdez in 1940-1941, McCutcheon honed his skills as an evidential photographer; as assistant commissioner in the state’s new Dept. of Labor, McCutcheon documented the cannery industry in Unalaska. From 1942 to 1944, he worked as district manager for the federal Office of Price Administration in Fairbanks, taking photographs of trading stations, communities and residents of northern Alaska; he sent an album of these photos to Washington, D.C., “to show them,” he said, “that things that applied in the South 48 didn’t necessarily apply to Alaska.” 1 1 Emanuel, Richard P. -

Chugach National Forest 2016 Visitor Guide

CHUGACH NATIONAL FOREST 2016 VISITOR GUIDE CAMPING WILDILFE VISITOR CENTERS page 10 page 12 page 15 Welcome Get Out and Explore! Hop on a train for a drive-free option into the Chugach National Forest, plan a multiple day trip to access remote to the Chugach National Forest! primitive campsites, attend the famous Cordova Shorebird Festival, or visit the world-class interactive exhibits Table of Contents at Begich, Boggs Visitor Center. There is something for everyone on the Chugach. From the Kenai Peninsula to The Chugach National Forest, one of two national forests in Alaska, serves as Prince William Sound, to the eastern shores of the Copper River Delta, the forest is full of special places. Overview ....................................3 the “backyard” for over half of Alaska’s residents and is a destination for visi- tors. The lands that now make up the Chugach National Forest are home to the People come from all over the world to experience the Chugach National Forest and Alaska’s wilderness. Not Eastern Kenai Peninsula .......5 Alaska Native peoples including the Ahtna, Chugach, Dena’ina, and Eyak. The only do we welcome international visitors, but residents from across the state travel to recreate on Chugach forest’s 5.4 million acres compares in size with the state of New Hampshire and National Forest lands. Whether you have an hour or several days there are options galore for exploring. We have Prince William Sound .............7 comprises a landscape that includes portions of the Kenai Peninsula, Prince Wil- listed just a few here to get you started. liam Sound, and the Copper River Delta. -

2017-Portage-Curve-Report

Seward Highway, MP 75-90 Rehabilitation Project - Portage Curve Project No.: OA3/58105 DESIGN STUDY REPORT STATE OF ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION AND PUBLIC FACILITIES PREPARED BY: Seawolf Engineering, Inc. 2900 Spirit Drive, Room 205 Anchorage, AK 99507 Revised June 2016 STATE OF ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION AND PUBLIC FACILITIES DESIGN AND ENGINEERING SERVICES – CENTRAL REGION DESIGN STUDY REPORT For Seward Highway, MP 75-90 Rehabilitation Project – Portage Curve Project No.: OA3/58105 Written by: Zach Cuddihy, Kelsey Copley, Kyle Powell, Grant Warnke Prepared by: __________________________________ Zach Cuddihy Date Student Project Manager Concur by: __________________________________ Randy D. Vanderwood, P.E. Date Project Manager Concur by: __________________________________ James E. Amundsen, P.E. Date Chief, Highway Design Approved: __________________________________ Wolfgang E. Junge, P.E. Date Preconstruction Engineer NOTICE TO USERS This report reflects the thinking and design decisions at the time of publication. Changes frequently occur during the evolution of the design process, so persons who may rely on information contained in this document should check with the Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities for the most current design. Contact the Design Project Manager, Randy Vanderwood, P.E. at (907) 269-0586 for this information. PLANNING CONSISTENCY This document has been prepared by the Department of Transportation and Public Facilities according to currently acceptable design standards and Federal regulations, and with the input offered by the local government and public. The Department's Planning Section has reviewed and approved this report as being consistent with present community planning. CERTIFICATION We hereby certify that this document was prepared in accordance with Section 520.4.1 of the current edition of the Department's Highway Preconstruction Manual and CFR Title 23, Highway Section 771.111(h). -

Glaciers, Wildlife, and Amazing Scenery

N EN AN A CANTWELL RIV ER DENALI NATIONAL PARK MAP NORTH OF GE SEE PAGEA N106 A R TO FAIRBANKS ANCHORAGE SK LA DENALI PARK SEE PAGE 114 KANTISHNAA DENALI PARK RD ER IV R A TN LI U CH PETERSVILLE K A Y H E I TALKEETNA N L T T N N A A TALKEETNA SPUR RD R I R V I E V R E TALKEETNA MAP R SEE PAGE 98 INS SKWENT TA NA N RI OU VE M R A TN EE LK TA EAST OF ANCHORAGE SEE PAGE 118 MATANUSKA HATCHER PASS RD CHICKALOON GLACIER WILLOW CALM WATERS WILD SIGHTS PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND WASILLA PALMER COACH AND RAIL OPTIONS GETTING THERE IS HALF THE FUN! EKLUTNAKN IK R BELUGA DENALI IV RIVER ER Our cruises easily connect with rail or coach service so you can relax in RIVER EA GL S E IN perfect comfort while viewing glaciers, wildlife, and amazing scenery. R TA I N V U E O M ANCHORAGE R H C A 1 G U H C TU RN COOK INLET AG AI N A RM GIRDWOOD GLACIERS Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center Mile marker 79 WHITTIER PORTAGE KENAI PRINCE 1 SEWARD WILLIAM COOPER SOUND HOMER LANDING DAY CRUISES & COACH Map: Courtesy of alaska.org May 5 – September 30 | Daily DRIVING TO WHITTIER? Allow 1.5 hours from Anchorage. Travel south on the Seward Highway to $219 Adults | $129 Child 2-11 +tax/fees mile 79. Turn left onto the Portage Glacier Road to access Whittier through the Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel. -

Whittier Wildlife Viewing Guide

[email protected]. ildlife W ur O atch W or email the chamber at at chamber the email or All other photos © ADF&G. © photos other All Fish and Game and Fish Armstrong ©Bob w/chick Eagle • Sanger ©Gerry rookery kittiwake & cover eagle Bald • • whittieralaskachamber.org whittieralaskachamber.org Photos of Department Alaska Commerce website at www. at website Commerce Whittier Chamber of of Chamber Whittier www.wildlifeviewing.alaska.gov and tours, visit the Greater Greater the visit tours, and For information on lodging lodging on information For Anchorage residents, tourists, anglers and hunters. hunters. and anglers tourists, residents, Anchorage visit www.wildlifeviewing.alaska.gov. www.wildlifeviewing.alaska.gov. visit earthquake but rebuilt and is today a popular destination for for destination popular a today is and rebuilt but earthquake For more information on wildlife viewing across Alaska, Alaska, across viewing wildlife on information more For Whittier suffered heavy damage in a tsunami after the 1964 1964 the after tsunami a in damage heavy suffered Whittier residents. The Buckner Building is abandoned. abandoned. is Building Buckner The residents. in stores and online. online. and stores in Guide Viewing Wildlife Coastal Towers are now condominiums housing most of Whittier’s Whittier’s of most housing condominiums now are Towers Alaska’s South South Alaska’s for check and trail coastal the along Whittier were built for soldiers after the war. The Begich Begich The war. the after soldiers for built were Whittier and Unalaska. Pick up community brochures brochures community up Pick Unalaska. and during World War II. Two large buildings that dominate dominate that buildings large Two II. -

MINERAL INVESTIGATIONS in the CHUGACH NATIONAL FOREST, ALASKA (PENINSULA STUDY AREA) by Robert B

MINERAL INVESTIGATIONS IN THE CHUGACH NATIONAL FOREST, ALASKA (PENINSULA STUDY AREA) by Robert B. Hoekzema and Gary E. Sherman Alaska Field Operations Center, Anchorage, Alaska *************************************************** In-House Report UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Donald P. Hodel, Secretary BUREAU OF MINES Robert C. Horton, Director CONTENTS Page Abstract......................................................... Introduction..................................................... Size, location, and access.................................... Physiographic setting.......................................... Previous work.................................................... Acknowledgments.................................................. Land status...................................................... Mining history................................................... General geologic setting......................................... Chugach terrane. ...................................... Intrusives.............. ...................................... Structure...................................................... Faults....................................................... Folds........................................................ Present investigations. .................................... Literature research. ...................................... Field programs ...................................... Sample collecting and processing procedure..................... Criteria used for qualitative resource assessment............. -

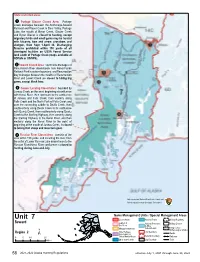

2021-2022 Alaska Hunting Regulations Effective July 1, 2021 Through June 30, 2022 Unit 7 Seward See Map on Page 58 for State Restricted Areas in Unit 7

State restricted areas: 1 Portage Glacier Closed Area: Portage Creek drainages between the Anchorage-Seward Railroad and Placer Creek in Bear Valley, Portage Lake, the mouth of Byron Creek, Glacier Creek and Byron Glacier is closed to hunting, except migratory birds and small game may be hunted with falconry, bow and arrow, crossbow, and shotgun, from Sept 1-April 30. Discharging firearms prohibited within 150 yards of all developed facilities on USDA Forest Service land south of Portage Creek (maps available at ADF&G or USFWS). 2 Seward Closed Area: south side drainages of Resurrection River downstream from Kenai Fjords National Park’s eastern boundary, and Resurrection Bay drainages between the mouths of Resurrection River and Lowell Creek are closed to taking big game, except black bear. 3 Cooper Landing Closed Area: bounded by Juneau Creek, on the west, beginning at confluence with Kenai River, then upstream to the confluence of Juneau and Falls Creek, then easterly along Falls Creek and the North Fork of Falls Creek and over the connecting saddle to Devils Creek, then southeasterly along Devils Creek to its confluence with Quartz Creek, then southeasterly along Quartz Creek to the Sterling Highway, then westerly along the Sterling Highway to the Kenai River, and then westerly along the Kenai River to the point of beginning at the mouth of Juneau Creek, is closed to taking Dall sheep and mountain goat. 4 Russian River Closed Area: consists of the area within 150 yards, and including the river, from t h e o u t l e t o f L o w e r R u s s i a n L a k e d o w n s t r e a m t o t h e Russian River/Kenai River confluence is closed to hunting during June and July. -

State of Alaska OFFICIAL ELECTION PAMPHLET November 8, 2016

State of Alaska OFFICIAL ELECTION PAMPHLET November 8, 2016 Decide Alaska’s FutureVote REGION II • Municipality of Anchorage • Matanuska-Susitna Borough PAGE 1 2016 REGION II Table of Contents General Election Day is Tuesday, November 8, 2016 Alaska’s Ballot Counting System .............................................................................. 3 Voting Information..................................................................................................... 4 Voter Assistance and Concerns................................................................................ 5 Language Assistance ............................................................................................... 6 Absentee Voting ....................................................................................................... 8 Absentee Ballot Application ...................................................................................... 9 Absentee Ballot Application Instructions................................................................. 10 Absentee Voting Locations .....................................................................................11 Polling Places ......................................................................................................... 12 Candidates for Elected Office ................................................................................. 13 Candidates for President, Vice President, US Senate, US Representative ............16 Candidates for House District 8 ......................................................................... -

Lu Liston Collection, B1989.016

REFERENCE CODE: AkAMH REPOSITORY NAME: Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center Bob and Evangeline Atwood Alaska Resource Center 625 C Street Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: 907-929-9235 Fax: 907-929-9233 Email: [email protected] Guide prepared by: Sara Piasecki, Archivist; Tim Remick, contractor; and Haley Jones, Museum volunteer TITLE: Lu Liston Collection COLLECTION NUMBER: B1989.016 OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Dates: circa 1899-1967 Extent: 21 linear feet Language and Scripts: The collection is in English. Name of creator(s): The following list includes photographers identified on negatives or prints in the collection, but is probably not a complete list of all photographers whose work is included in the collection: Alaska Shop Bornholdt Robert Bragaw Nellie Brown E. Call Guy F. Cameron Basil Clemons Lee Considine Morris Cramer Don Cutter Joseph S. Dixon William R. Dahms Julius Fritschen George Dale Roy Gilley Glass H. W. Griffin Ted Hershey Denny C. Hewitt Eve Hamilton Sidney Hamilton E. A. Hegg George L. Johnson Johnson & Tyler R. C. L. Larss & Duclos Sydney Laurence George Lingo Lucien Liston William E. Logemann Lomen Bros. Steve McCutcheon George Nelson Rossman F. S. Andrew Simons H. W. Steward Thomas Kodagraph Shop Marcus V. Tyler H. A. W. Bradford Washburn Ward Wells Frank Wright Jr. Administrative/Biographical History: Lucien Liston was a longtime Alaskan businessman and artist, and has been described as the last of a long line of drug store photographers who provided images for sale to the traveling public. He was born in 1910 in Eugene, Oregon, and came to Alaska in 1929, living first in Juneau, where he met and married Edna Reindeau. -

Matthew P. Mullaney Slides, B2014.019

REFERENCE CODE: AkAMH REPOSITORY NAME: Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center Bob and Evangeline Atwood Alaska Resource Center 625 C Street Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: 907-929-9235 Fax: 907-929-9233 Email: [email protected] Guide prepared by: Sara Piasecki, Photo Archivist TITLE: Matthew P. Mullaney Slides COLLECTION NUMBER: B2014.019 OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Dates: circa 1939-1953 Extent: 3 boxes, 0.625 linear feet Language and Scripts: The collection is in English. Name of creator(s): Matthew P. Mullaney, Nell Mullaney, LeRoy Flora, Alaska Color Slides, Katherine Boswell, Trevor Davis, 4th Avenue Fotoshop, Gairvette, Reuel Griffin, Robert A. Hall, J & H Sales Co., Steve McCutcheon, Ordway Photo Shop, Howard C. Robinson, Schallerer’s Photo Shop, Stewart’s Photo Shop, Everett J. Wilde, E. Wolf, Wyman’s Photo Service Administrative/Biographical History: Matthew P. “Bud” Mullaney (1890-1953) served as Commissioner of Taxation for the Territory of Alaska from circa 1942 until his death in 1953. He and his wife Nell had no children. Dr. Flora is likely LeRoy Flora, who practiced in Anchorage for a time in the 1940s-early 1950s with his wife Gunda (1909-1996), a nurse at the Alaska Psychiatric Institute. Scope and Content Description: The collection consists of 500 color 35mm slides, both personal and commercially-produced, of Alaskan scenes from locations throughout the state. The majority of the personal photos were taken by Matthew and Nell Mullaney, with a small portion bearing the name “Dr. Flora” and different handwriting. Several disasters are documented, including the sinking of the Princess Kathleen (1952) and fires at Wright’s Drug Store in Palmer and the Maynard hospital in Nome (1948). -

2021 VG Offline Rate Card.Indd

VISIT ANCHORAGE ADVERTISING OPPORTUNITIES CALL TO ADVERTISE: OFFICIAL GUIDE TO GLACIERSGiant glaciers line the land around Anchorage, and visitors are treated to SPIFF CHAMBERS 907.257.2321 an up-close view. CAMBRIA PATZ 907.265.2377 ALASKA KATIE REEVES 907.257.2374 AND SURROUNDING AREAS MAIN OFFICE 907.276.4118 Portage Glacier A long, low rumble. A sharp crack of ice. A walk from Begich, Boggs Visitor Center to ROADSIDE WONDER jagged block of ice crumbling into the water nearby Byron Glacier, for a close-up view Getting a look at these icy wonders below. Glaciers are one of Alaska’s most of these magical ice formations – all just 15 doesn’t take a lot of effort. In this part awe-inspiring sights, and with dozens of miles south of Girdwood, or an hour from of Alaska, even a scenic drive along them located within just 50 miles of the city, downtown Anchorage. the Seward Highway has glacier views. Anchorage makes it easy to see these crystal The posh Seven Glaciers Restaurant in blue ice formations firsthand, whether you Girdwood pairs fine dining with alpine approach by foot, boat, or private plane. views of seven hanging glaciers. The aerial tram ride to the restaurant is just an ICY MARVELS appetizer of the panoramic vistas in store. Glaciers are among Anchorage’s most Checking out a glacier can be as easy as Twentymile Glacier popular stops. From day cruises to pulling off the road at a scenic overlook. flightseeing and easy hikes to extreme North of Anchorage, stop along the Glenn treks, start your glacial exploration in BY AIR AND SEA Highway for a view of Matanuska Glacier. -

Bell's Travel Guides

Bell’s Travel Guides Seward Highway Road Log Mile by Mile Description of the Seward Highway so you always know what lies ahead. Anchorage, Alaska to Seward, Alaska This 127 mile/204 km highway has been designated a National Forest Scenic Byway. It connects the cities of Anchorage and Seward traveling past salt water bays, ice-blue glaciers, and alpine valleys. The first 50 miles of the highway twists and turns along the base of the Chugach Mountains, and the shore of Turnagain Arm. The 37-foot tides here are exceeded only by those in Nova Scotia's Bay of Fundy. The waters racing out of the inlet expose miles of mud flats and when they return, frequently create 6-foot bore tides. Thirty-eight miles from Seward, the route joins the Sterling Highway which continues down the peninsula to Soldotna, Kenai, Ninilchik, Anchor Point, and Homer. The Alaska Railroad parallels the Seward Highway to Portage, where it has a branch line to Whittier Alaska -port for the Alaska Marine Ferry System. Alaska Marine Ferry System has service to Valdez and Cordova on the and the rest of Southeast Alaska. The railroad also serves Seward, which was the original starting point of the Alaska Railroad. Just past the turn-off for Portage Glacier, you will enter the Kenai Peninsula Borough - over 25,000 square miles of scenic park lands, forests, volcanoes, glaciers, coastline, rivers, and unique communities. Here it is easy to try your luck at hooking a world record king salmon or a giant halibut, photograph a Russian church or see sea lions, whales, and a kaleidoscope of seabirds all on the same day! Warning: The mudflats along the coast from Anchorage to Portage (Turnagain Arm) exhibit quicksand-like conditions.