NUMBER 81 SPRING 2012 – TABLE Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EM Forster's Howards End and Virginia Woolfs Mrs. Dalloway

The Metropolis and the Oceanic Metaphor: E.M. Forster's Howards End and Virginia Woolfs Mrs. Dalloway Melissa Baty UH 450 / Fall 2003 Advisor: Dr. Jon Hegglund Department of English Honors Thesis ************************* PASS WITH DISTINCTION Thesis Advisor Signature Page 1 of 1 TO THE UNIVERSITY HONORS COLLEGE: As thesis advisor for Me~~'Y3 ~3 I have read this paper and find it satisfactory. 1 1-Z2.-03 Date " http://www.wsu.edu/~honors/thesis/AdvisecSignature.htm 9/22/2003 Precis Statement ofResearch Problem: In the novels Howards End by E.M. Forster and Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf, the two authors illwninate their portrayal ofearly twentieth-century London and its rising modernity with oceanic metaphors. My research in history, cultural studies, literary criticism, and psychoanalytic theory aimed to discover why and to what end Forster and Woolf would choose this particular image for the metropolis itselfand for social interactions within it. Context of the Problem: My interpretation of the oceanic metaphor in the novels stems from the views of particular theorists and writers in urban psychology and sociology (Anthony Vidler, Georg Simmel, Jack London) and in psychoanalysis (Sigmund Freud, particularly in his correspondence with writer Romain Rolland). These scholars provide descriptions ofthe oceanic in varying manners, yet reflect the overall trend in the period to characterizing life experience, and particularly experiences in the city, through images and metaphors ofthe sea. Methods and Procedures: The research for this project entailed reading a wide range ofhistorically-specific background regatg ¥9fSter, W661f~ eity of I .Q~e various academic areas listed above in order to frame my conclusions about the novels appropriately. -

Works on Giambattista Vico in English from 1884 Through 2009

Works on Giambattista Vico in English from 1884 through 2009 COMPILED BY MOLLY BLA C K VERENE TABLE OF CON T EN T S PART I. Books A. Monographs . .84 B. Collected Volumes . 98 C. Dissertations and Theses . 111 D. Journals......................................116 PART II. Essays A. Articles, Chapters, et cetera . 120 B. Entries in Reference Works . 177 C. Reviews and Abstracts of Works in Other Languages ..180 PART III. Translations A. English Translations ............................186 B. Reviews of Translations in Other Languages.........192 PART IV. Citations...................................195 APPENDIX. Bibliographies . .302 83 84 NEW VICO STUDIE S 27 (2009) PART I. BOOKS A. Monographs Adams, Henry Packwood. The Life and Writings of Giambattista Vico. London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reprinted New York: Russell and Russell, 1970. REV I EWS : Gianturco, Elio. Italica 13 (1936): 132. Jessop, T. E. Philosophy 11 (1936): 216–18. Albano, Maeve Edith. Vico and Providence. Emory Vico Studies no. 1. Series ed. D. P. Verene. New York: Peter Lang, 1986. REV I EWS : Daniel, Stephen H. The Eighteenth Century: A Current Bibliography, n.s. 12 (1986): 148–49. Munzel, G. F. New Vico Studies 5 (1987): 173–75. Simon, L. Canadian Philosophical Reviews 8 (1988): 335–37. Avis, Paul. The Foundations of Modern Historical Thought: From Machiavelli to Vico. Beckenham (London): Croom Helm, 1986. REV I EWS : Goldie, M. History 72 (1987): 84–85. Haddock, Bruce A. New Vico Studies 5 (1987): 185–86. Bedani, Gino L. C. Vico Revisited: Orthodoxy, Naturalism and Science in the ‘Scienza nuova.’ Oxford: Berg, 1989. REV I EWS : Costa, Gustavo. New Vico Studies 8 (1990): 90–92. -

Off the Pedestal, on the Stage: Animation and De-Animation in Art

Off the Pedestal; On the Stage Animation and De-animation in Art and Theatre Aura Satz Slade School of Fine Art, University College, London PhD in Fine Art 2002 Abstract Whereas most genealogies of the puppet invariably conclude with robots and androids, this dissertation explores an alternative narrative. Here the inanimate object, first perceived either miraculously or idolatrously to come to life, is then observed as something that the live actor can aspire to, not necessarily the end-result of an ever evolving technological accomplishment. This research project examines a fundamental oscillation between the perception of inanimate images as coming alive, and the converse experience of human actors becoming inanimate images, whilst interrogating how this might articulate, substantiate or defy belief. Chapters i and 2 consider the literary documentation of objects miraculously coming to life, informed by the theology of incarnation and resurrection in Early Christianity, Byzantium and the Middle Ages. This includes examinations of icons, relics, incorrupt cadavers, and articulated crucifixes. Their use in ritual gradually leads on to the birth of a Christian theatre, its use of inanimate figures intermingling with live actors, and the practice of tableaux vivants, live human figures emulating the stillness of a statue. The remaining chapters focus on cultural phenomena that internalise the inanimate object’s immobility or strange movement quality. Chapter 3 studies secular tableaux vivants from the late eighteenth century onwards. Chapter 4 explores puppets-automata, with particular emphasis on Kempelen's Chess-player and the physical relation between object-manipulator and manipulated-object. The main emphasis is a choreographic one, on the ways in which live movement can translate into inanimate hardness, and how this form of movement can then be appropriated. -

Anon Is Not Dead: Towards a History of Anonymous Authorship in Early-Twentieth-Century Britain Emily Kopley

Document generated on 09/30/2021 7:56 p.m. Mémoires du livre Studies in Book Culture Anon is Not Dead: Towards a History of Anonymous Authorship in Early-Twentieth-Century Britain Emily Kopley Générations et régénérations du livre Article abstract The Generation and Regeneration of Books In 1940, Virginia Woolf blamed the printing press for killing the oral tradition Volume 7, Number 2, Spring 2016 that had promoted authorial anonymity: “Anon is dead,” she pronounced. Scholarship on the printed word has abundantly recognized that, far from URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1036861ar being dead, Anon remained very much alive in Britain through the end of the DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1036861ar nineteenth century. Even in the twentieth century, Anon lived on, among particular groups and particular genres, yet little scholarship has addressed this endurance. Here, after defining anonymity and sketching its history in the See table of contents late nineteenth and early twentieth century, I offer three findings. First, women had less need for anonymity as they gained civil protections elsewhere, but anonymity still appealed to writers made vulnerable by their marginalized Publisher(s) identities or risky views. Second, in the early twentieth century the genre most likely to go unsigned was autobiography, in all its forms. Third, on rare Groupe de recherches et d’études sur le livre au Québec occasions, which I enumerate, strict anonymity achieves what pseudonymity cannot. I conclude by suggesting that among British modernist authors, the ISSN decline of practiced anonymity stimulated desired anonymity and the prizing 1920-602X (digital) of anonymity as an aesthetic ideal. -

The Chemistry Club a Number of Interesting Movies Were Enjoyed by the Chemistr Y Club This Year

Hist The Chronicle Coll CHS of 1942 1942 Edited by the Students of Chelmsford High School 2 ~{ Chelmsford High School Foreword The grcalest hope for Lh<' cider comes f rorn l h<' spiril of 1\mcrirnn youth. E xcmplilit>cl hy the cha r aclcristics of engerne%. f rnnk,wss. amhilion. inili,lli\·c'. and faith. il is one of the uplil'ling factor- of 01 1r li\'CS. \ \ 'iLhoul it " ·e could ,, <'II question th<' f1 1Lurc. \ \ 'ith il we rnusl ha\'C Lh e assurallce of their spirit. \ Ve hope you\\ ill nlld in the f oll o,, ing page:- some incli cnlion of your pasl belief in our young people as well as sornP pncouragcmenl for the rnnlinualion of your faiLh. The Chronicle of 1942 ~ 3 CONTENTS Foreword 2 Con lent 3 ·I 5 Ceo. ' . \\' righl 7 Lucian 11. 13urns 9 r undi y 11 13oard of l:cl ilors . Ser I iors U11dcrgrnd1rnlcs 37 .l11 nior Class 39 Sopho111ore Cb ss ,JO F reshma11 C lass 4 1 S port s 43 /\ct i,·ilies I lumor 59 Autographs 66 Chelmsford High School T o find Llw good in llE'. I've learned lo Lum T o LhosE' \\'ilh w hom my da ily lol is rasl. \ \/hose grncious h111n11n kindness ho lds me fast. Throughout the ycnr I w a nl to learn. T ho1 1gh war may rage and nations overlum. Those deep simplirilies Lhat li\'C and lasl. To M. RIT !\ RY J\N vV e dedicate our yearbook in gra te/ul recognition o/ her genial manner. -

The Posthumanistic Theater of the Bloomsbury Group

Maine State Library Digital Maine Academic Research and Dissertations Maine State Library Special Collections 2019 In the Mouth of the Woolf: The Posthumanistic Theater of the Bloomsbury Group Christina A. Barber IDSVA Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/academic Recommended Citation Barber, Christina A., "In the Mouth of the Woolf: The Posthumanistic Theater of the Bloomsbury Group" (2019). Academic Research and Dissertations. 29. https://digitalmaine.com/academic/29 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Maine State Library Special Collections at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Academic Research and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN THE MOUTH OF THE WOOLF: THE POSTHUMANISTIC THEATER OF THE BLOOMSBURY GROUP Christina Anne Barber Submitted to the faculty of The Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy August, 2019 ii Accepted by the faculty at the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in partial fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. COMMITTEE MEMBERS Committee Chair: Simonetta Moro, PhD Director of School & Vice President for Academic Affairs Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts Committee Member: George Smith, PhD Founder & President Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts Committee Member: Conny Bogaard, PhD Executive Director Western Kansas Community Foundation iii © 2019 Christina Anne Barber ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iv Mother of Romans, joy of gods and men, Venus, life-giver, who under planet and star visits the ship-clad sea, the grain-clothed land always, for through you all that’s born and breathes is gotten, created, brought forth to see the sun, Lady, the storms and clouds of heaven shun you, You and your advent; Earth, sweet magic-maker, sends up her flowers for you, broad Ocean smiles, and peace glows in the light that fills the sky. -

The Historical Novel” an Audio Program from This Goodly Land: Alabama’S Literary Landscape

Supplemental Materials for “The Historical Novel” An Audio Program from This Goodly Land: Alabama’s Literary Landscape Program Description Interviewer Maiben Beard and Dr. Bert Hitchcock, Professor emeritus, of the Auburn University Department of English discuss the historical novel. Reading List Overviews and Bibliographies • Butterfield, Herbert. The Historical Novel: An Essay. Cambridge, Eng.: The University Press, 1924. Rpt. Folcroft, Penn.: Folcroft Library Editions, 1971. Rpt. Norwood, Penn.: Norwood Editions, 1975. • Carnes, Mark C., ed. Novel History: Historians and Novelists Confront America’s Past (and Each Other). New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. • Coffey, Rosemary K., and Elizabeth F. Howard. America as Story: Historical Fiction for Middle and Secondary Schools. Chicago: American Library Association, 1997. • Dekker, George. The American Historical Romance. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987. • Dickinson, A. T. American Historical Fiction. New York: Scarecrow Press, 1958. Rpt. New York: Scarecrow Press, 1963. • Henderson, Harry B. Versions of the Past: The Historical Imagination in American Fiction. New York: Oxford University Press, 1974. • Holman, C. Hugh. The Immoderate Past: The Southern Writer and History. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1977. • Leisy, Earnest E. The American Historical Novel. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1950. • Lukács, Georg [György]. The Historical Novel. Trans. Hannah and Stanley Mitchell. London: Merlin Press, 1962. • Matthews, Brander. The Historical Novel and Other Essays. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1901. [An online version of The Historical Novel and Other Essays is available from Google Book Search at http://books.google.com/books?id=wA1bAAAAMAAJ.] • VanMeter, Vandelia L. America in Historical Fiction: A Bibliographic Guide. Englewood, Colo.: Libraries Unlimited, 1997. -

Inventory Acc.3721 Papers of the Scottish Secretariat and of Roland

Inventory Acc.3721 Papers of the Scottish Secretariat and of Roland Eugene Muirhead National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland Summary of Contents of the Collection: BOXES 1-40 General Correspondence Files [Nos.1-1451] 41-77 R E Muirhead Files [Nos.1-767] 78-85 Scottish Home Rule Association Files [Nos.1-29] 86-105 Scottish National Party Files [1-189; Misc 1-38] 106-121 Scottish National Congress Files 122 Union of Democratic Control, Scottish Federation 123-145 Press Cuttings Series 1 [1-353] 146-* Additional Papers: (i) R E Muirhead: Additional Files Series 1 & 2 (ii) Scottish Home Rule Association [Main Series] (iii) National Party of Scotland & Scottish National Party (iv) Scottish National Congress (v) Press Cuttings, Series 2 * Listed to end of SRHA series [Box 189]. GENERAL CORRESPONDENCE FILES BOX 1 1. Personal and legal business of R E Muirhead, 1929-33. 2. Anderson, J W, Treasurer, Home Rule Association, 1929-30. 3. Auld, R C, 1930. 4. Aberdeen Press and Journal, 1928-37. 5. Addressall Machine Company: advertising circular, n.d. 6. Australian Commissioner, 1929. 7. Union of Democratic Control, 1925-55. 8. Post-card: list of NPS meetings, n.d. 9. Ayrshire Education Authority, 1929-30. 10. Blantyre Miners’ Welfare, 1929-30. 11. Bank of Scotland Ltd, 1928-55. 12. Bannerman, J M, 1929, 1955. 13. Barr, Mrs Adam, 1929. 14. Barton, Mrs Helen, 1928. 15. Brown, D D, 1930. -

The Republican Journal: Vol. 84, No. 39

The Republican Joitrnai ' 7rtix>n7b4 BELFAST, MAINE. THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 26, 1912. NUMBER 7i«T~ lournal. Fred vs oif Today’s Rackliff F p'"' supreme Judicial Court. Flagg. Defaulted and E H vs Nellie R Goodwin. continued for Goodwin Libt, Conte"'* judgment. Knowlton; Johnson OBITUARY. [L.ard of Trade Supreme Libby. PERSONAL. Judge George F. Hanson, of Calais, Charles B Eaton vs Fred Curtis. Non personalT Li TheSta , Obituary. .The Sec- suited! Alfred G Bolin Libt, vs Rebecca N Bolin. Cen- Presiding.; Knowlton; Brown. Jennie S., widow of the late G. Tib- J. W. Cavalry..Jackson Libby. Henry Manson, Esq., of Pittsfield was a busi- f J“fl?!,De Personal. C W Waiter Whitehead went to ond «**'", ,,.ft Societies.. The Stephenson vs C H I betts, died Sept. 15th at her home in Rockland ness Boston grand jury reported Wednesday, return- Shuman, appealed Pearl Crockett vs L J Crockett. Sweetser & caller in Belfast Monday Friday. for a week's visit. The Murder of Capt Referred to Eben F Littlefield. after three months' illness. Her decline be- t Points ing eight indictments which were not made Brown; Buzzell Morse; Dunton & Morse. Mrs. Eugenia L. Cobbett of W L vs C E soon after Dover, N. H., is Freeman rr p?" Washington Whisperings.. Gray Mitchell and C B gan very the death of her O. is son |C- public until later in the week. They were a* Cook! J. Baum Safe & Lock Co vs Frank M Fair- husband, relatives in Roberts visiting his in gasno o... fumes. -The Man Who j visiting Belfast and vicinity. -

And Mention of American Indians

Updated: December 2020 CHAPTER 7 - THE AMERICAN BAHÁ'Í MAGAZINE January 1970: 1) NABOHR: Past, Present, and Future. The North American Bahá'í Office for Human Rights was established in January 1986. It is reported here that this office sponsored conferences for action on Human Rights in 20 leading cities and on a Canadian Reserve. There is a Photo here of presenter giving the address at the "American Indian and Human Rights" conference in Gallup, New Mexico. p. 3. 2) A program illustration entitled; "A World View" and it includes an Indian image. p. 7. February 1970: checked March 1970: 1) Bahá'í Education Conference Draws Overflow Attendance. More than 500 Bahá'ís from all over the U.S. come to this event. The only non Bahá'í speaker at the conference, Mrs. De Lee has a long record of civil rights activity in South Carolina. Her current project was to help 300 Indian school children in Dorchester County get into the public school. They were considered to be white until they tried to get their children in the public schools there. They were told they couldn't go to the public schools. A Freedom school was set up in an Indian community to teach Indian children and Mrs. Lee is still working towards getting them into the public school. pp. 1, 5. 2) News Briefs: The Minorities Teaching Committee of Albuquerque, NM held a unity Feast recently concurrent with the feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe, which is significant to the Mexican and American Indian populations of the area. -

Roots and Routes Poetics at New College of California

Roots and Routes Poetics at New College of California Edited by Patrick James Dunagan Marina Lazzara Nicholas James Whittington Series in Creative Writing Studies Copyright © 2020 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Creative Writing Studies Library of Congress Control Number: 2020935054 ISBN: 978-1-62273-800-7 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image by Max Kirkeberg, diva.sfsu.edu/collections/kirkeberg/bundles/231645 All individual works herein are used with permission, copyright owned by their authors. Selections from "Basic Elements of Poetry: Lecture Notes from Robert Duncan Class at New College of California," Robert Duncan are © the Jess Collins Trust. -

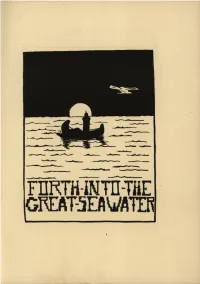

1923 03 the Classes.Pdf

I Legends of the tribe, Forth-into-the-Great-Sea-Water LEGEND ONE T was autumn 1919 and the leaves of the maples were red and yellow along the streams. A tribe destined to be called Forth- into-the-Great-Sea-Water came to the camping ground of the Delawares. One of the three tribes greeting them looked upon them with scorn. The new tribe must prove itself worthy to dwell on the camping ground. The scornful ones inflicted many tortures to test their bravery. One dark night they painted black the faces of the helpless maidens. They gave them many unkinId words. They made them wear ivory rattles about their necks. But before many suns had set the strangers acquired merit in the eyes of the scornful. * And the friendly ones were proud of the progress of the young tribe. One time before the sun rose to drive away the mists of the night, the maidens of Forth-into-the-Great-Sea-Water stole forth from their wigwams. They raised their banner bearing the mystic figures, '23, to the top of a tall pole. The scornful ones became more displeased. They tried many times to lower the hated banner of their enemy. When they could not succeed their anger increased. At last they called friendly braves down the trail to help them. One night the maidens who wore the rattles dressed as braves. They bade the other tribes to the Great Lodge for a night of dancing. Although this new tribe had now acquired much wisdom, it needed counsel.