Notes Why Mandatory Vaccination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vaccines and Autism: What You Should Know | Vaccine Education

Q A Vaccines and Autism: What you should know Volume& 1 Summer 2008 Some parents of children with autism are concerned that vaccines are the cause. Their concerns center on three areas: the combination measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine; thimerosal, a mercury-containing preservative previously contained in several vaccines; and the notion that babies receive too many vaccines too soon. Q. What are the symptoms of autism? Q. Does the MMR vaccine cause autism? A. Symptoms of autism, which typically appear during the A. No. In 1998, a British researcher named Andrew Wakefi eld fi rst few years of life, include diffi culties with behavior, social raised the notion that the MMR vaccine might cause autism. skills and communication. Specifi cally, children with autism In the medical journal The Lancet, he reported the stories of may have diffi culty interacting socially with parents, siblings eight children who developed autism and intestinal problems and other people; have diffi culty with transitions and need soon after receiving the MMR vaccine. To determine whether routine; engage in repetitive behaviors such as hand fl apping Wakefi eld’s suspicion was correct, researchers performed or rocking; display a preoccupation with activities or toys; a series of studies comparing hundreds of thousands of and suffer a heightened sensitivity to noise and sounds. children who had received the MMR vaccine with hundreds Autism spectrum disorders vary in the type and severity of of thousands who had never received the vaccine. They found the symptoms they cause, so two children with autism may that the risk of autism was the same in both groups. -

COVID-19 Vaccinations with an Update from 12/16/2020

COVID-19 Vaccinations with an Update from 12/16/2020 Michael A. Kaufmann, MD, FACEP, FAEMS State EMS Medical Director Indiana Department of Homeland Security Hot Off The Press • 12/11/2020 • Vaccine advisers to the US Food and Drug Administration voted Thursday to recommend the agency grant emergency use authorization to Pfizer and BioNTech's coronavirus vaccine. • Seventeen members of the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee voted yes, four voted no and one abstained. • "The question is never when you know everything. It's when you know enough and I think we know enough now to say that this appears to be our way out of this awful, awful mess," Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and a member of the committee, told CNN's Wolf Blitzer after the vote. • "That's why I voted yes." FDA Concerns • Several committee members expressed concern about reports of allergic reactions in two people who were vaccinated in Britain, which authorized Pfizer's vaccine ahead of the US. • FDA staff said that, as with any vaccines, paperwork would accompany the Pfizer vaccine to warn against administering it to anyone with a history of severe allergic reactions to vaccines or allergies to any of the ingredients of the vaccine. • The FDA will now decide whether to accept the recommendation, but has signaled that it will issue the EUA for the vaccine. • ACIP has a meeting scheduled for Friday, and expects to vote during a meeting scheduled for Sunday. • Operation Warp Speed officials say they will start shipping the vaccine within 24 hours of FDA authorization. -

Myocarditis After SARS-Cov-2 Vaccination: True, True, and … Related? Sean T

Myocarditis After SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination: True, True, and … Related? Sean T. O’Leary, MD, MPH,a,b Yvonne A. Maldonado, MDc In this month’s issue of Pediatrics, compiled cases through personal Marshall et al report a case series communication rather than through describing seven 14- to 19-year-old a systematic surveillance system. male individuals who developed Clearly, this approach could symptomatic myocarditis after the introduce reporting bias, and a case second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech series cannot establish causality. coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID- Another critical point to consider is 19) vaccine.1 The authors report that that the reported cases mirror the the symptoms began between 2 and seasonal prevalence, sex, and age 4 days after the second dose and that profile of background cases of aAdult and Child Consortium for Health Outcomes all 7 patients experienced rapid myocarditis, thereby complicating an Research and Delivery Science, Anschutz Medical Campus, resolution of symptoms. This case assessment of a potential association University of Colorado and Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, Colorado, bDepartment of Pediatrics, Anschutz series is published in the context of with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. The Medical Campus, University of Colorado, Aurora, Colorado, other media reports of myocarditis authors themselves note in their cDepartment of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, Stanford in young adults, mostly male, from discussion the high background rate University, Stanford, California 2 the US military and from Israel as of myocarditis in adolescent and Opinions expressed in these commentaries are those of well as a recent increase in reports young adult male individuals,4 the authors and not necessarily those of the American Academy of Pediatrics or its Committees. -

Diseases Subject to the International Health Regulations

Diseases Subject to the International Health Regulations Cholera, yellow fever, and plague cases and deaths reported in the Region of the Americas up to 15 October 1980 Country and Yellow fever administrative Cholera Plague subdivision Cases Cases Deaths Cases BOLIVIA - 46 39 15 Cochabamba - 12 8 - La Paz - 32 30 15 Santa Cruz - 1 1 - Tarija - 1 - BRAZIL - 25 22 69 Ceará - - - 62 Goiás - 20 19 Maranhao - 4 2 - Pernambuco - - - 7 Rondónia - 1 1 - CANADA 3 - - - Quebec 1 - - Saskatchewan 2 - - COLOMBIA - 7 7 - Cesar - 1 1 - Guaviare - 1 1 - Meta - 1 1 - Norte de Santander - 1 1 - Putumayo - 3 3 - ECUADOR - 2 - Napo - 2 PERU - 24 19 - Ayacucho - 8 7 - Junín - 7 4 - San Martín - 7 7 - ...- 2 1 - UNITED STATES 8 - - 13 California 6 - 2 Maryland 1 - Nevada - - - 2 New Mexico - - - 9 Pennsylvania 1 - - VENEZUELA - 1 1 - Mérida - 1 1 -None. ... Data not available. I Accidental Smallpox Vaccination in Venezuela On 31 July 1980 a report was received that the previous vaccine (lot No. 48 produced by the National Institute of day a 10-month old child weighing 10 kg, who had been Health), rehydrated in the diluent of the Merieux Lab- taken for measles vaccination in Barquisimeto, Lara oratory measles vaccine. In a way, the accident provided State, had accidentally received in the left arm a sub- an opportunity for reinforcing the principle that those in cutaneous injection of 25 doses of freeze-dried smallpox charge of programs should supervise the immunizations 5 more closely. It also provided an example of what can The fact that smallpox vaccine was administered at all happen, and the state epidemiologists who were attend- prompts yet another important comment. -

Key Messages and Answers About Vaccine Safety MANUAL for HEALTH WORKERS

Key Messages and Answers about Vaccine Safety MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKERS Key Messages and Answers about Vaccine Safety MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKERS Washington, D.C., 2021 Key Messages and Answers about Vaccine Safety. Manual for Health Care Workers PAHO/FPL/IM/COVID-19/21-0027 © Pan American Health Organization, 2021 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO license (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this license, this work may be copied, redistributed, and adapted for non-commercial purposes, provided the new work is issued using the same or equivalent Creative Commons license and it is appropriately cited. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) endorses any specific organization, product, or service. Use of the PAHO logo is not permitted. All reasonable precautions have been taken by PAHO to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall PAHO be liable for damages arising from its use. ii KEY MESSAGES AND ANSWERS ABOUT VACCINE SAFETY Contents Acknowledgements VI Introduction 1 History of vaccines up to the present 2 Chapter 1. Immunization schedules in the regular program 4 1.1 Key messages 5 1.2 Questions and answers -

Vaccine Lessons from the Early 1800S: the Boon of Jenner and Covid-19

Vaccine lessons from the early 1800s: The Boon of Jenner and Covid-19 Item Type Blog Authors Takemoto, Hanna Publication Date 2021-05-10 Abstract COVID-19 vaccines allowed the world to open back up after months of quarantine, social distancing, and masking. This post traces the history of vaccines and the hesitancy to vaccinate from Edward Jenner's discovery of the smallpox vaccine. The post... Keywords Dissertation; Boon of Jenner; Vaccines; Jenner, Edward, 1749-1823; Smallpox; COVID-19 (Disease); University of Maryland, Baltimore. School of Medicine; Smallpox; COVID-19; Vaccines Download date 01/10/2021 16:54:33 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10713/16241 Vaccine lessons from the early 1800s: The Boon of Jenner and Covid-19 Posted May 10, 2021 Written by Hanna Takemoto, Spring 2021 HSHSL Intern Hanna Takemoto is a new graduate of the MLIS program at the University of Maryland, College Park. She recently completed an internship at the HSHSL where she worked on a collection of 19th century School of Medicine dissertations. As the world continues to grapple with the relentless coronavirus, vaccines remain the most promising tool in our arsenal. In fact, we are in the midst of what can be described as the most ambitious vaccination effort in human history. The unprecedented speed of the Covid-19 vaccine development has been a source of pride and hope, but also anxiety. According to the latest estimates by the U.S. Census Bureau, 15% of Americans do not plan on getting vaccinated against Covid-19. When we consider the successful vaccination campaigns of the 20th century that eradicated polio, tuberculosis, and measles, vaccine hesitancy may seem like a modern phenomenon fuelled by the online spread of misinformation. -

Smallpox Vaccine and Vaccination in the Intensified Smallpox Eradication Programme

CHAPTER 11 SMALLPOX VACCINE AND VACCINATION IN THE INTENSIFIED SMALLPOX ERADICATION PROGRAMME Contents Page Introduction 540 Vaccine requirements for the Intensified Smallpox Eradica- tion Programme 541 Providing the finance 541 Shortfalls in vaccines-quality and quantity 542 WHO survey of vaccine producers 543 Methods of vaccine production 543 Strains of vaccinia virus 545 Number of doses per container 545 Initial potency 546 Heat stability 546 Bacterial count 547 Establishment of the WHO reference centres for smallpox vaccine 547 Development of improved vaccines 548 Meeting of experts (March 1968) 549 Production of freeze-dried vaccine 551 Continuing quality control of smallpox vaccine 554 Testing samples of vaccine 554 Visits by consultants 555 Reference vaccine 555 Seed lots of vaccine 556 Evaluation of testing methods 557 Improvements in vaccine quality 559 Vaccine production in endemic countries 563 Donations of vaccine and their distribution 564 New vaccination techniques 567 The bifurcated needle 567 Jet injectors 573 Modification to vaccination procedures 580 Preparation of skin 580 Neonatal vaccination 580 539 5 40 SMALLPOX AND ITS ERADICATION Page The search for new vaccines 580 Selection of vaccinia virus strains of low patho- genicity 581 Attenuated strains 583 Inactivated vaccines 587 Production of vaccine in eggs and tissue culture 588 Silicone ointment vaccine 590 Efficacy of vaccination 590 INTRODUCTION In May 1980 the Thirty-third World Health Assembly, after it had declared that Vaccination against smallpox had been smallpox had been eradicated throughout the practised in virtually every country of the world, recommended that smallpox vacci- world, and in many on a large scale, when the nation should be discontinued, except for in- Intensified Smallpox Eradication Programme vestigators at special risk . -

Vaccine Policy Statement

VACCINE POLICY STATEMENT We firmly believe in the effectiveness of vaccines to prevent serious illness and to save lives. We firmly believe in the safety of our vaccines. We firmly believe that all children and young adults should receive all of the recommended vaccines according to the schedule published by the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention and the American Academy of Pediatrics. We firmly believe, based on all available literature, evidence and current studies, that vaccines do not cause autism or other developmental disabilities. We firmly believe that thimerosal, a preservative that has been in vaccines for decades, does not cause autism or other developmental disabilities. None of our current vaccines contain thimerosal except for the injectable influenza (flu) vaccine for children over three years of age. We firmly believe that vaccinating children and young adults may be the single most important health-promoting intervention we perform as healthcare providers, and that you can perform as parents/caregivers. The recommended vaccines and their schedule given are the results of years and years of scientific study and data gathering on millions of children by thousands of our brightest scientists and physicians. These things being said, we recognize that there has always been and will likely always be controversy surrounding vaccination. Indeed, Benjamin Franklin, persuaded by his brother, was opposed to smallpox vaccine until scientific data convinced him otherwise. Tragically, he had delayed inoculating his favorite son, Franky, who contracted smallpox and died at the age of 4, leaving Ben with a lifetime of guilt and remorse. Quoting Mr. Franklin’s autobiography: “In 1736, I lost one of my sons, a fine boy of four years old, by the smallpox…I long regretted bitterly, and still regret that I had not given it to him by inoculation. -

New Smallpox Vaccine Found Safer Than Existing Vaccines

APRIL 2009 • WWW.SKINANDALLERGYNEWS.COM INFECTIOUS DISEASES 37 Gardasil Prevents Warts, HPV Misunderstood, Feared HPV Infection in Males In One Border Community BY PATRICE WENDLING diagnosis of HPV as a diagnosis of BY MIRIAM E. TUCKER ACIP from the American Academy of Fam- cancer. They expressed their fears of ily Physicians. ispanic men and women liv- cancer and their belief that, once di- ATLANTA — The human papillomavirus In the randomized, double-blind, placebo- Hing on the United States–Mex- agnosed, it is “essentially a death vaccine was efficacious in preventing persis- controlled trial, three doses of Gardasil or ico border have little understanding sentence.” The women said they tent infections and genital warts caused by placebo were given at 0, 2, and 6 months. about the human papillomavirus would be reluctant to disclose their HPV strains 6, 11, 16, and 18 in a Merck-spon- Mean follow-up for this analysis was 30 and its role in the etiology of cer- HPV status to their partners be- sored study of 4,065 males aged 16-26 years. months of a planned total of 36. The study vical cancer, according to a small cause they believed they would be The findings were presented by Dr. Richard population, which came from 18 different prospective study. accused of infidelity. Men initially M. Haupt at a meeting of the Centers for Dis- countries, included 3,463 heterosexual males Not only were there very low lev- expressed anger at the possibility of ease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Com- aged 16-23 years and 602 males aged 16-26 who els of knowledge among these res- an HPV diagnosis, attributing it to mittee on Immunization Practices. -

Mandatory Vaccinations: Precedent and Current Laws

Mandatory Vaccinations: Precedent and Current Laws Kathleen S. Swendiman Legislative Attorney March 10, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RS21414 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Mandatory Vaccinations: Precedent and Current Laws Summary Historically, the preservation of the public health has been the primary responsibility of state and local governments, and the authority to enact laws relevant to the protection of the public health derives from the state’s general police powers. With regard to communicable disease outbreaks, these powers may include the enactment of mandatory vaccination laws. This report provides an overview of the legal precedent for mandatory vaccination laws, and of state laws that require certain individuals or populations, including school-aged children and health care workers, to be vaccinated against various communicable diseases. Also discussed are state laws providing for mandatory vaccinations during a public health emergency or outbreak of a communicable disease. Federal jurisdiction over public health matters derives from the Commerce Clause of the United States Constitution, which states that Congress shall have the power “[t]o regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States ... ” Congress has enacted requirements regarding vaccination of immigrants seeking entry into the United States, and military regulations require American troops to be immunized against a number of diseases. The Secretary of Health and Human Services has authority under the Public Health Service Act to issue regulations necessary to prevent the introduction, transmission, or spread of communicable diseases from foreign countries into the states or from state to state. Current federal regulations do not include any mandatory vaccination programs; rather, when compulsory measures are needed, measures such as quarantine and isolation are generally utilized to halt the spread of communicable diseases. -

Over 100 Years of Developing Vaccines*

Over 100 years of developing vaccines* 1963 1971 1981 1990 2005 Merck licenses its Measles, mumps, First plasma- PedavaxHIB® ProQuad® (Measles, first measles vaccine and rubella derived hepatitis B [Haemophilus b Mumps, Rubella and in the US trivalent vaccine vaccine licensed Conjugate Varicella Virus introduced Vaccine Vaccine Live) licensed 1895 Merck’s Dr. Hilleman 1983 (Meningococcal Protein H.K. Mulford Co. isolates the mumps 1977 PNEUMOVAX® 23 Conjugate)] licensed 2006 Merck licenses a (pneumococcal introduces first virus used to create RotaTeq® (Rotavirus vaccine against vaccine polyvalent) 2014 diphtheria antitoxin the first mumps 1995 Vaccine, Live, Oral, pneumococcal licensed GARDASIL®9 vaccine VARIVAX® Pentavalent) licensed disease (Varicella Virus (Human Papillomavirus 1898 9-valent Vaccine, 1967 1986 Vaccine Live) licensed ZOSTAVAX® (Zoster H.K. Mulford Co. Merck introduces the 1978 RECOMBIVAX HB® Recombinant) licensed introduces its Vaccine Live) licensed first vaccine against M-M-R® II Hepatitis B Vaccine smallpox vaccine 1996 mumps (Measles, Mumps, (Recombinant) VAQTA® (Hepatitis A GARDASIL® [Human and Rubella, licensed Vaccine, Inactivated) Papillomavirus 1969 Vaccine Live), the licensed Quadrivalent (Types 6, Merck introduces updated 11, 16,and 18) the first vaccine combination HiB and Hepatitis B Vaccine, against rubella vaccine, combination vaccine Recombinant] licensed introduced licensed 1890s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000s 2010s *Merck and its predecessor companies have a history with vaccines that dates back more than 100 years. In 1898, the H. K. Mulford Company produced its first batch of smallpox vaccine. In 1929, the H. K. Mulford Company was purchased by the Sharp & Dohme (S&D) Company of Baltimore. In April 1953, Sharp & Dohme merged with Merck & Company, Inc., becoming Merck Sharp & Dohme. -

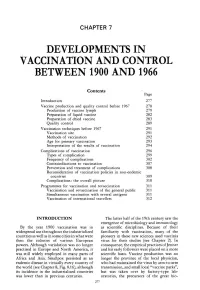

Chapter 7. Developments in Vaccination and Control Between

CHAPTER 7 DEVELOPMENTS IN VACCINATION AND CONTROL BETWEEN 1900 AND 1966 Contents Page Introduction 277 Vaccine production and quality control before 1967 278 Production of vaccine lymph 279 Preparation of liquid vaccine 282 Preparation of dried vaccine 283 Quality control 289 Vaccination techniques before 1967 291 Vaccination site 291 Methods of vaccination 292 Age for primary vaccination 293 Interpretation of the results of vaccination 294 Complications of vaccination 296 Types of complication 299 Frequency of complications 302 Contraindications to vaccination 307 Prevention and treatment of complications 308 Reconsideration of vaccination policies in non-endemic countries 309 Complications : the overall picture 310 Programmes for vaccination and revaccination 311 Vaccination and revaccination of the general public 311 Simultaneous vaccination with several antigens 311 Vaccination of international travellers 312 INTRODUCTION The latter half of the 19th century saw the emergence of microbiology and immunology By the year 1900 vaccination was in as scientific disciplines . Because of their widespread use throughout the industrialized familiarity with vaccination, many of the countries as well as in some cities in what were pioneers in these new sciences used vaccinia then the colonies of various European virus for their studies (see Chapter 2) . In powers . Although variolation was no longer consequence, the empirical practices of Jenner practised in Europe and North America, it and his early followers were placed on a more was still widely employed in many parts of scientific basis . Vaccine production was no Africa and Asia . Smallpox persisted as an longer the province of the local physician, endemic disease in virtually every country of who had maintained the virus by arm-to-arm the world (see Chapter 8, Fig.