(OTC) Antibiotics in the European Union and Norway, 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Nanobiosensors in Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

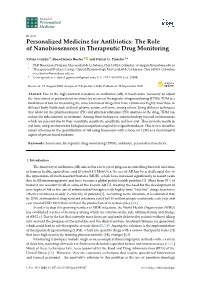

Journal of Personalized Medicine Review Personalized Medicine for Antibiotics: The Role of Nanobiosensors in Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Vivian Garzón 1, Rosa-Helena Bustos 2 and Daniel G. Pinacho 2,* 1 PhD Biosciences Program, Universidad de La Sabana, Chía 140013, Colombia; [email protected] 2 Therapeutical Evidence Group, Clinical Pharmacology, Universidad de La Sabana, Chía 140013, Colombia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +57-1-8615555 (ext. 23309) Received: 21 August 2020; Accepted: 7 September 2020; Published: 25 September 2020 Abstract: Due to the high bacterial resistance to antibiotics (AB), it has become necessary to adjust the dose aimed at personalized medicine by means of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). TDM is a fundamental tool for measuring the concentration of drugs that have a limited or highly toxic dose in different body fluids, such as blood, plasma, serum, and urine, among others. Using different techniques that allow for the pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) analysis of the drug, TDM can reduce the risks inherent in treatment. Among these techniques, nanotechnology focused on biosensors, which are relevant due to their versatility, sensitivity, specificity, and low cost. They provide results in real time, using an element for biological recognition coupled to a signal transducer. This review describes recent advances in the quantification of AB using biosensors with a focus on TDM as a fundamental aspect of personalized medicine. Keywords: biosensors; therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), antibiotic; personalized medicine 1. Introduction The discovery of antibiotics (AB) ushered in a new era of progress in controlling bacterial infections in human health, agriculture, and livestock [1] However, the use of AB has been challenged due to the appearance of multi-resistant bacteria (MDR), which have increased significantly in recent years due to AB mismanagement and have become a global public health problem [2]. -

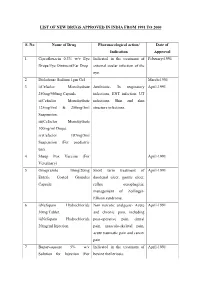

List of New Drugs Approved in India from 1991 to 2000

LIST OF NEW DRUGS APPROVED IN INDIA FROM 1991 TO 2000 S. No Name of Drug Pharmacological action/ Date of Indication Approval 1 Ciprofloxacin 0.3% w/v Eye Indicated in the treatment of February-1991 Drops/Eye Ointment/Ear Drop external ocular infection of the eye. 2 Diclofenac Sodium 1gm Gel March-1991 3 i)Cefaclor Monohydrate Antibiotic- In respiratory April-1991 250mg/500mg Capsule. infections, ENT infection, UT ii)Cefaclor Monohydrate infections, Skin and skin 125mg/5ml & 250mg/5ml structure infections. Suspension. iii)Cefaclor Monohydrate 100mg/ml Drops. iv)Cefaclor 187mg/5ml Suspension (For paediatric use). 4 Sheep Pox Vaccine (For April-1991 Veterinary) 5 Omeprazole 10mg/20mg Short term treatment of April-1991 Enteric Coated Granules duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, Capsule reflux oesophagitis, management of Zollinger- Ellison syndrome. 6 i)Nefopam Hydrochloride Non narcotic analgesic- Acute April-1991 30mg Tablet. and chronic pain, including ii)Nefopam Hydrochloride post-operative pain, dental 20mg/ml Injection. pain, musculo-skeletal pain, acute traumatic pain and cancer pain. 7 Buparvaquone 5% w/v Indicated in the treatment of April-1991 Solution for Injection (For bovine theileriosis. Veterinary) 8 i)Kitotifen Fumerate 1mg Anti asthmatic drug- Indicated May-1991 Tablet in prophylactic treatment of ii)Kitotifen Fumerate Syrup bronchial asthma, symptomatic iii)Ketotifen Fumerate Nasal improvement of allergic Drops conditions including rhinitis and conjunctivitis. 9 i)Pefloxacin Mesylate Antibacterial- In the treatment May-1991 Dihydrate 400mg Film Coated of severe infection in adults Tablet caused by sensitive ii)Pefloxacin Mesylate microorganism (gram -ve Dihydrate 400mg/5ml Injection pathogens and staphylococci). iii)Pefloxacin Mesylate Dihydrate 400mg I.V Bottles of 100ml/200ml 10 Ofloxacin 100mg/50ml & Indicated in RTI, UTI, May-1991 200mg/100ml vial Infusion gynaecological infection, skin/soft lesion infection. -

Milk and Dairy Beef Drug Residue Prevention

Milk and Dairy Beef Drug Residue Prevention Producer Manual of Best Management Practices 2014 Connecting Cows, Cooperatives, Capitol Hill, and Consumers www.nmpf.org email: [email protected] National Milk Producers Federation (“NMPF”) does not endorse any of the veterinary drugs or tests identified on the lists in this manual. The lists of veterinary drugs and tests are provided only to inform producers what products may be available, and the producer is responsible for determining whether to use any of the veterinary drugs or tests. All information regarding the veterinary drugs or tests was obtained from the products’ manufacturers or sponsors, and NMPF has made no further attempt to validate or corroborate any of that information. NMPF urges producers to consult with their veterinarians before using any veterinary drug or test, including any of the products identified on the lists in this manual. In the event that there might be any injury, damage, loss or penalty that results from the use of these products, the manufacturer of the product, or the producer using the product, shall be responsible. NMPF is not responsible for, and shall have no liability for, any injury, damage, loss or penalty. ©2014 National Milk Producers Federation Cover photo courtesy of DMI FOREWORD The goal of our nation’s dairy farmers is to produce the best tasting and most wholesome milk possible. Our consumers demand the best from us and we meet the needs of our consumers every day. Day in and day out, we provide the best in animal husbandry and animal care practices for our animals. -

Tyrothricin Πan Underrated Agent for the Treatment of Bacterial Skin

REVIEW Engelhard Arzneimittel GmbH & Co KG, Niederdorfelden, Germany Tyrothricin – An underrated agent for the treatment of bacterial skin infections and superficial wounds? C. LANG , C. STAIGER Received February 22, 2015, accepted March 23, 2016 Dr. Christopher Lang, Engelhard Arzneimittel GmbH & Co. KG, Herzbergstr. 3, 61138 Niederdorfelden, Germany [email protected] Pharmazie 71:299–305 (2016) doi: 10.1691/ph.2016.6038 The antimicrobial agent tyrothricin is a representative of the group of antimicrobial peptides (AMP). It is produced by Bacillus brevis and consists of tyrocidines and gramicidins. The compound mixture shows activity against bacteria, fungi and some viruses. A very interesting feature of AMPs is the fact, that even in vitro it is almost impossible to induce resistances. Therefore, this class of molecules is discussed as one group that could serve as next generation antibiotics and overcome the increasing problem of bacterial resistances. In daily practice, the application of tyrothricin containing formulations is relatively limited: It is used in sore throat medications and in agents for the healing of infected superficial and small-area wounds. However, due to the broad spectrum anti- microbial activity and the low risk of resistance development it is worth to consider further fields of application. 1. Introduction 2. Structure, production, properties A decade after Alexander Fleming published his findings on Tyrothricin is a mixture of polypeptides, consisting of 50 % - 70 % the antibiotic effect of penicillin in 1929 (Fleming 1929), René tyrocidines and 25 % to 50 % gramicidins (Ph.Eur. 8th edition Dubos discovered tyrothricin, a polypeptide mixture obtained 2014). The group of tyrocidines are basic, cyclic peptides, whereas from Bacillus brevis, which was isolated from soil. -

Tetracycline and Sulfonamide Antibiotics in Soils: Presence, Fate and Environmental Risks

processes Review Tetracycline and Sulfonamide Antibiotics in Soils: Presence, Fate and Environmental Risks Manuel Conde-Cid 1, Avelino Núñez-Delgado 2 , María José Fernández-Sanjurjo 2 , Esperanza Álvarez-Rodríguez 2, David Fernández-Calviño 1,* and Manuel Arias-Estévez 1 1 Soil Science and Agricultural Chemistry, Faculty Sciences, University Vigo, 32004 Ourense, Spain; [email protected] (M.C.-C.); [email protected] (M.A.-E.) 2 Department Soil Science and Agricultural Chemistry, Engineering Polytechnic School, University Santiago de Compostela, 27002 Lugo, Spain; [email protected] (A.N.-D.); [email protected] (M.J.F.-S.); [email protected] (E.Á.-R.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 October 2020; Accepted: 13 November 2020; Published: 17 November 2020 Abstract: Veterinary antibiotics are widely used worldwide to treat and prevent infectious diseases, as well as (in countries where allowed) to promote growth and improve feeding efficiency of food-producing animals in livestock activities. Among the different antibiotic classes, tetracyclines and sulfonamides are two of the most used for veterinary proposals. Due to the fact that these compounds are poorly absorbed in the gut of animals, a significant proportion (up to ~90%) of them are excreted unchanged, thus reaching the environment mainly through the application of manures and slurries as fertilizers in agricultural fields. Once in the soil, antibiotics are subjected to a series of physicochemical and biological processes, which depend both on the antibiotic nature and soil characteristics. Adsorption/desorption to soil particles and degradation are the main processes that will affect the persistence, bioavailability, and environmental fate of these pollutants, thus determining their potential impacts and risks on human and ecological health. -

List of Union Reference Dates A

Active substance name (INN) EU DLP BfArM / BAH DLP yearly PSUR 6-month-PSUR yearly PSUR bis DLP (List of Union PSUR Submission Reference Dates and Frequency (List of Union Frequency of Reference Dates and submission of Periodic Frequency of submission of Safety Update Reports, Periodic Safety Update 30 Nov. 2012) Reports, 30 Nov. -

)&F1y3x PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX to THE

)&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE )&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 3 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. Product CAS No. Product CAS No. ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACTODIGIN 36983-69-4 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ADAFENOXATE 82168-26-1 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ADAMEXINE 54785-02-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ADAPALENE 106685-40-9 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ADAPROLOL 101479-70-3 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ADATANSERIN 127266-56-2 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ADEFOVIR 106941-25-7 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ADELMIDROL 1675-66-7 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 ADEMETIONINE 17176-17-9 ACAPRAZINE 55485-20-6 ADENOSINE PHOSPHATE 61-19-8 ACARBOSE 56180-94-0 ADIBENDAN 100510-33-6 ACEBROCHOL 514-50-1 ADICILLIN 525-94-0 ACEBURIC ACID 26976-72-7 ADIMOLOL 78459-19-5 ACEBUTOLOL 37517-30-9 ADINAZOLAM 37115-32-5 ACECAINIDE 32795-44-1 ADIPHENINE 64-95-9 ACECARBROMAL 77-66-7 ADIPIODONE 606-17-7 ACECLIDINE 827-61-2 ADITEREN 56066-19-4 ACECLOFENAC 89796-99-6 ADITOPRIM 56066-63-8 ACEDAPSONE 77-46-3 ADOSOPINE 88124-26-9 ACEDIASULFONE SODIUM 127-60-6 ADOZELESIN 110314-48-2 ACEDOBEN 556-08-1 ADRAFINIL 63547-13-7 ACEFLURANOL 80595-73-9 ADRENALONE -

Oxytetracycline for Recurrent Blepharitis and Br J Ophthalmol: First Published As 10.1136/Bjo.79.1.42 on 1 January 1995

42 British rournal of Ophthalmology 1995; 79: 42-45 Placebo controlled trial of fusidic acid gel and oxytetracycline for recurrent blepharitis and Br J Ophthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.79.1.42 on 1 January 1995. Downloaded from rosacea D V Seal, P Wright, L Ficker, K Hagan, M Troski, P Menday Abstract topical and systemic anti-staphylococcal A prospective, randomised, double blind, antibiotics in addition to anti-inflammatory partial crossover, placebo controlled trial therapy. has been conducted to compare the Fusidic acid has been in clinical use since performance of topical fusidic acid gel 1962 and is particularly effective against (Fucithalmic) and oral oxytetracycline as staphylococci. It has a steroid structure but no treatment for symptomatic chronic glucocorticoid activity. A new gel preparation blepharitis. Treatment success was containing 1% microcrystalline fusidic acid judged both by a reduction in symptoms (Fucithalmic) has recently been shown to be and clinical examination before and after effective for treating acute bacterial conjunc- therapy. Seventy five per cent of patients tivitis and for reducing the staphylococcal lid with blepharitis and associated rosacea flora before surgery.5-8 were symptomatically improved by Oxytetracycline has been selected for the fusidic acid gel and 500/0 by oxytetra- treatment of patients with chronic blepharitis cycline, but fewer (35%/o) appeared to as it has both anti-inflammatory and anti- benefit from the combination. Patients staphylococcal properties.9 10 It has been with chronic blepharitis of other aetiolo- demonstrated to be effective in a controlled gies did not respond to fusidic acid gel but trial in ocular rosacea for comeal infiltrates and 25% did benefit from oxytetracycline and conjunctival hyperaemiaII and in non-ocular 300/0 from the combination. -

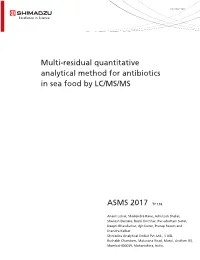

Multi-Residual Quantitative Analytical Method for Antibiotics in Sea Food by LC/MS/MS

PO-CON1742E Multi-residual quantitative analytical method for antibiotics in sea food by LC/MS/MS ASMS 2017 TP 198 Anant Lohar, Shailendra Rane, Ashutosh Shelar, Shailesh Damale, Rashi Kochhar, Purushottam Sutar, Deepti Bhandarkar, Ajit Datar, Pratap Rasam and Jitendra Kelkar Shimadzu Analytical (India) Pvt. Ltd., 1 A/B, Rushabh Chambers, Makwana Road, Marol, Andheri (E), Mumbai-400059, Maharashtra, India. Multi-residual quantitative analytical method for antibiotics in sea food by LC/MS/MS Introduction Antibiotics are widely used in agriculture as growth LC/MS/MS method has been developed for quantitation of enhancers, disease treatment and control in animal feeding multi-residual antibiotics (Table 1) from sea food sample operations. Concerns for increased antibiotic resistance of using LCMS-8040, a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer microorganisms have prompted research into the from Shimadzu Corporation, Japan. Simultaneous analysis environmental occurrence of these compounds. of multi-residual antibiotics often exhibit peak shape Assessment of the environmental occurrence of antibiotics distortion owing to their different chemical nature. To depends on development of sensitive and selective overcome this, autosampler pre-treatment feature was analytical methods based on new instrumental used [1]. technologies. Table 1. List of antibiotics Sr.No. Name of group Name of compound Number of compounds Flumequine, Oxolinic Acid, Ciprofloxacin, Danofloxacin, Difloxacin.HCl, 1 Fluoroquinolones 8 Enrofloxacin, Sarafloxacin HCl Trihydrate, -

The Systemic Activity and Phytotoxic Effects of Fungicides Effective Against Certain Cotton Pathogens

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1970 The ysS temic Activity and Phytotoxic Effects of Fungicides Effective Against Certain Cotton Pathogens. Robert Gene Davis Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Davis, Robert Gene, "The ysS temic Activity and Phytotoxic Effects of Fungicides Effective Against Certain Cotton Pathogens." (1970). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1776. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1776 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 71-3408 DAVIS, Robert Gene, 1932- THE SYSTEMIC ACTIVITY AND PHYTOTOXIC EFFECTS' OF FUNGICIDES EFFECTIVE AGAINST CERTAIN COTTON PATHOGENS. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1970 Agriculture, plant pathology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE SYSTEMIC ACTIVITY AND FHYTOTOXIC EFFECTS OF FUNGICIDES EFFECTIVE AGAINST CERTAIN COTTON PATHOGENS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Botany and Plant Pathology by Robert Gene Davis B.S., Mississippi State University, 1953 M.S., Mississippi State University, 1968 May, 1970 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The contributions to this study by others is recognized and appre ciated. Dr. J. A. -

Multi-Residue Determination of Sulfonamide and Quinolone Residues in Fish Tissues by High Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

674 Journal of Food and Drug Analysis, Vol. 20, No. 3, 2012, Pages 674-680 doi:10.6227/jfda.2012200315 Multi-Residue Determination of Sulfonamide and Quinolone Residues in Fish Tissues by High Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) CHUNG-WEI TSAI1, CHAN-SHING LIN1 AND WEI-HSIEN WANG1,2* 1. Division of Marine Biotechnology, Asia-Pacific Ocean Research Center, National Sun Yat-Sen University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, R.O.C. 2. National Museum of Marine Biology and Aquarium, Pingtung, Taiwan, R.O.C. (Received: August 30, 2010; Accepted: April 26, 2012) ABSTRACT A LC-MS/MS method was validated for the simultaneous quantification of 4 quinolones (oxolinic acid, enrofloxacine, ciprofloxacine, norfloxacine) and 4 sulfonamides (sulfamethoxypyridazine, sulfadoxine, sulfadimidine, sulfamerazine) on fish muscle following the Euro- pean Union’s (EU) criteria for the analysis of veterinary drug residues in foods. One gram of sample was extracted by acidic acetonitrile (0.5 mL of 0.1% formic acid in 7 mL of ACN), followed by LC-MS/MS analysis using an electrospray ionization interface. Typical recoveries of the 4 quinolones in the fish tissues ranged from 85 to 104%. While those of the sulfonamides ranged from 75 to 94% at the fortification level of 5.0 μg/kg. The decision limits (CCα) and detection capabilities (CCβ) of the quinolones were 1.35 to 2.10 μg/kg and 1.67 to 2.75 μg/kg, respectively. Meanwhile, the CCα and CCβ of the sulfonamides ranged from 1.62 μg/kg to 2.53μg/kg and 2.01μg/kg to 3.13 μg/kg, respectively. -

Tyrothricin Zur Behandlung Von Erkrankungen Im Mund- Und Rachenraum Antrag Auf Unterstellung Unter Die Verschreibungspflicht

Tyrothricin zur Behandlung von Erkrankungen im Mund- und Rachenraum Antrag auf Unterstellung unter die Verschreibungspflicht 0 Sicherheitsaspekte • 80% aller Halsschmerzerkrankungen sind viral bedingt. • In mehr als in 80% der Erkrankungen - ist eine therapeutische Wirksamkeit von Tyrothricin nicht gegeben. - erfolgt die Anwendung eines Wirkstoffs bei fehlender Indikation. - erfolgt eine Fehlanwendung des Arzneimittels, daher sind maximal Nebenwirkungen für den Patienten möglich. • Eine Risikominimierung einer Tyrothricin-Anwendung für das Individuum und die Gesellschaft ist nur durch eine gezielte Therapieempfehlung durch den Arzt möglich - Beratungspflicht des Apothekers besteht, allerdings keine Diagnosemöglichkeit. - Differenzierung für Patienten hinsichtlich einer viralen oder bakteriellen Infektion ist nicht möglich. - Test zur Differenzierung dürfen nicht in der Apotheke durchgeführt oder an Laien abgegeben werden. • Eine Reihe von EU-Länder hat bereits die Zulassung für Lokalantibiotika bei Halsschmerzen aufgrund eines negativen Nutzen-Risiko-Verhältnisses zurückgezogen. Einige pharmazeutische Unternehmer haben freiwillig die Produkte angepasst oder vom Markt genommen. 1 Sicherheitsaspekte Land neubewertetes Produkt (Wirkstoff) Jahr Begründung aus regulatorischer Sicht Alle topischen Antibiotika Topische Antibiotika (Fusafungin, Bacitracin, Gramicidin, FR (Fusafungine, Bacitracine, 2005 Tyrothricin) wurden wegen ihrer zu AMR führenden Dosierung Gramicidine, Tyrothricine) vom Markt genommen GSK Consumer Healthcare Schweiz AG ersetzte