Teething Complications, a Persisting Misconception IAN L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

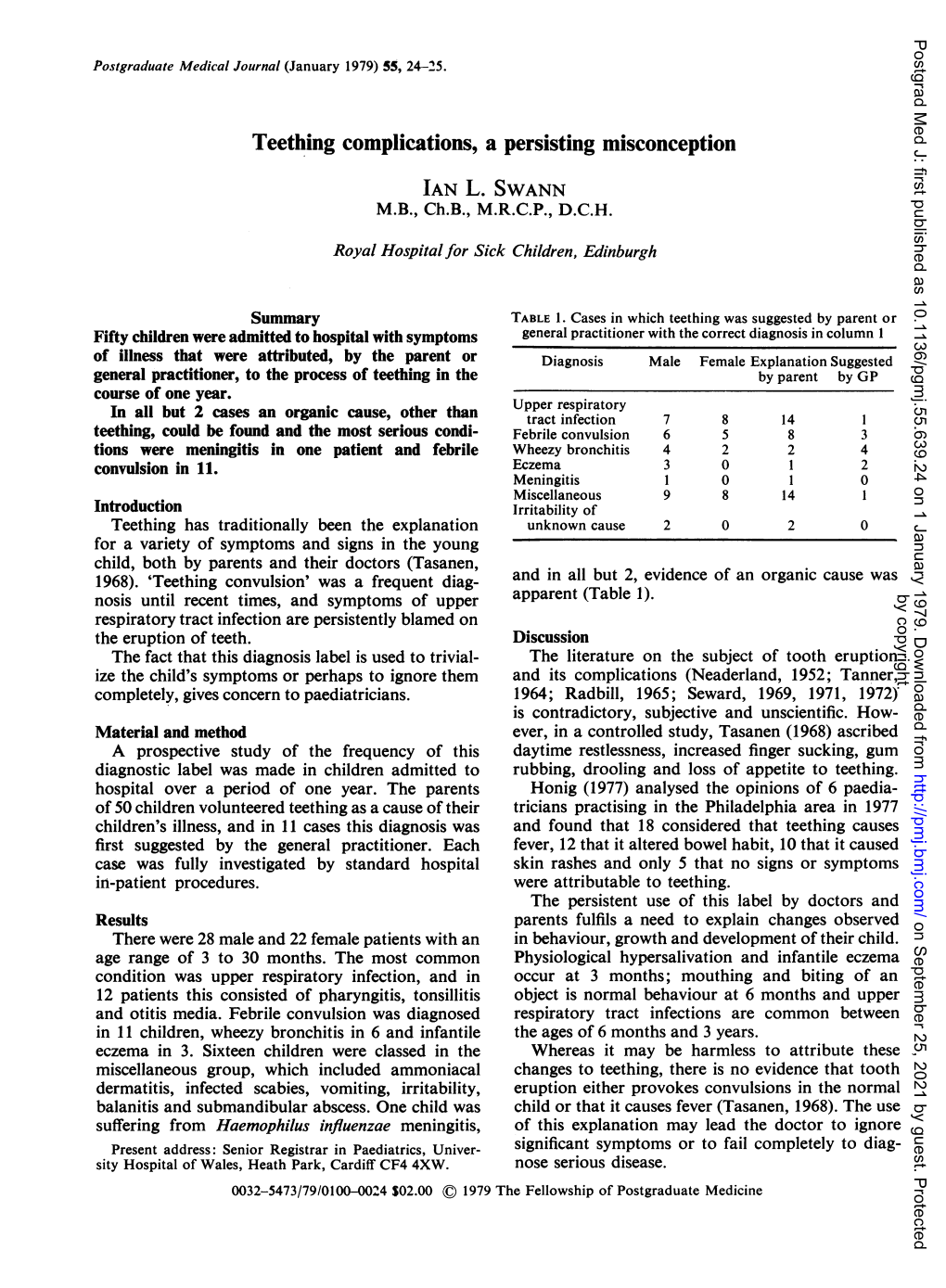

-

Homologies of the Anterior Teeth in Lndriidae and a Functional Basis for Dental Reduction in Primates

Homologies of the Anterior Teeth in lndriidae and a Functional Basis for Dental Reduction in Primates PHILIP D. GINGERICH Museum of Paleontology, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 KEY WORDS Dental reduction a Lemuriform primates . Indriidae . Dental homologies - Dental scraper . Deciduous dentition - Avahi ABSTRACT In a recent paper Schwartz ('74) proposes revised homologies of the deciduous and permanent teeth in living lemuriform primates of the family Indriidae. However, new evidence provided by the deciduous dentition of Avahi suggests that the traditional interpretations are correct, specifically: (1) the lat- eral teeth in the dental scraper of Indriidae are homologous with the incisors of Lemuridae and Lorisidae, not the canines; (2) the dental formula for the lower deciduous teeth of indriids is 2.1.3; (3) the dental formula for the lower perma- nent teeth of indriids is 2.0.2.3;and (4)decrease in number of incisors during pri- mate evolution was usually in the sequence 13, then 12, then 11. It appears that dental reduction during primate evolution occurred at the ends of integrated in- cisor and cheek tooth units to minimize disruption of their functional integrity. Anterior dental reduction in the primate Schwartz ('74) recently reviewed the prob- family Indriidae illustrates a more general lem of tooth homologies in the dental scraper problem of direction of tooth loss in primate of Indriidae and concluded that no real evi- evolution. All living lemuroid and lorisoid pri- dence has ever been presented to support the mates (except the highly specialized Dauben- interpretation that indriids possess four lower tonid share a distinctive procumbent, comb- incisors and no canines. -

Pediatric Oral Pathology. Soft Tissue and Periodontal Conditions

PEDIATRIC ORAL HEALTH 0031-3955100 $15.00 + .OO PEDIATRIC ORAL PATHOLOGY Soft Tissue and Periodontal Conditions Jayne E. Delaney, DDS, MSD, and Martha Ann Keels, DDS, PhD Parents often are concerned with “lumps and bumps” that appear in the mouths of children. Pediatricians should be able to distinguish the normal clinical appearance of the intraoral tissues in children from gingivitis, periodontal abnormalities, and oral lesions. Recognizing early primary tooth mobility or early primary tooth loss is critical because these dental findings may be indicative of a severe underlying medical illness. Diagnostic criteria and .treatment recommendations are reviewed for many commonly encountered oral conditions. INTRAORAL SOFT-TISSUE ABNORMALITIES Congenital Lesions Ankyloglossia Ankyloglossia, or “tongue-tied,” is a common congenital condition characterized by an abnormally short lingual frenum and the inability to extend the tongue. The frenum may lengthen with growth to produce normal function. If the extent of the ankyloglossia is severe, speech may be affected, mandating speech therapy or surgical correction. If a child is able to extend his or her tongue sufficiently far to moisten the lower lip, then a frenectomy usually is not indicated (Fig. 1). From Private Practice, Waldorf, Maryland (JED); and Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Dentistry, Duke Children’s Hospital, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina (MAK) ~~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ PEDIATRIC CLINICS OF NORTH AMERICA VOLUME 47 * NUMBER 5 OCTOBER 2000 1125 1126 DELANEY & KEELS Figure 1. A, Short lingual frenum in a 4-year-old child. B, Child demonstrating the ability to lick his lower lip. Developmental Lesions Geographic Tongue Benign migratory glossitis, or geographic tongue, is a common finding during routine clinical examination of children. -

Oral Structure, Dental Anatomy, Eruption, Periodontium and Oral

Oral Structures and Types of teeth By: Ms. Zain Malkawi, MSDH Introduction • Oral structures are essential in reflecting local and systemic health • Oral anatomy: a fundamental of dental sciences on which the oral health care provider is based. • Oral anatomy used to assess the relationship of teeth, both within and between the arches The color and morphology of the structures may vary with genetic patterns and age. One Quadrant at the Dental Arches Parts of a Tooth • Crown • Root Parts of a Tooth • Crown: part of the tooth covered by enamel, portion of the tooth visible in the oral cavity. • Root: part of the tooth which covered by cementum. • Posterior teeth • Anterior teeth Root • Apex: rounded end of the root • Periapex (periapical): area around the apex of a tooth • Foramen: opening at the apex through which blood vessels and nerves enters • Furcation: area of a two or three rooted tooth where the root divides Tooth Layers • Enamel: the hardest calcified tissue covering the dentine in the crown of the tooth (96%) mineralized. • Dentine: hard calcified tissue surrounding the pulp and underlying the enamel and cementum. Makes up the bulk of the tooth, (70%) mineralized. Tooth Layers • Pulp: the innermost noncalsified tissues containing blood vessels, lymphatics and nerves • Cementum: bone like calcified tissue covering the dentin in the root of the tooth, 50% mineralized. Tooth Layers Tooth Surfaces • Facial: Labial , Buccal • Lingual: called palatal for upper arch. • Proximal: mesial , distal • Contact area: area where that touches the adjacent tooth in the same arch. Tooth Surfaces • Incisal: surface of an incisor which toward the opposite arch, the biting surface, the newly erupted “permanent incisors have mamelons”: projections of enamel on this surface. -

Effect of Posters and Mobile-Health Education Strategies on Teething Beliefs and Oral Health Knowledge Among Mothers in Nairobi

EFFECT OF POSTERS AND MOBILE-HEALTH EDUCATION STRATEGIES ON TEETHING BELIEFS AND ORAL HEALTH KNOWLEDGE AMONG MOTHERS IN NAIROBI. DR. REGINA MUTAVE JAMES REGISTRATION NUMBER: V91/96427/2014 Department of Periodontology/Community and Preventive Dentistry THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEGREE (PhD) IN COMMUNITY AND PREVENTIVE DENTISTRY, UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI DECLARATION: I, Regina Mutave James hereby declare that this is my original work and that it has not been submitted by any other person for research purpose, degree or otherwise in any other university or institution. Signed ………………………………………. Date ………………………………. Regina Mutave James R.M.J PhD Thesis - 2015 Page i SUPERVISORS’ DECLARATION This research thesis has been submitted for the fulfillment of the requirement for the award of PhD in Community and Preventive Dentistry with our approval as supervisors. Supervisors: Signed ………………………………..Date……………………………. Prof. Loice W. Gathece BDS., MPH., PhD( Nbi). Department of Periodontology/ Community and Preventive Dentistry, University of Nairobi. Signed ………………………………..Date……………………………. Prof. Arthur M. Kemoli BDS (Nbi)., MSc (UvA)., PhD (UvA). Department of Pediatric Dentistry and Orthodontics, University of Nairobi. R.M.J PhD Thesis - 2015 Page ii DEDICATION To the Almighty, for His unending Grace! R.M.J PhD Thesis - 2015 Page iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My PhD studies including this thesis were made possible by the financial support that I received from the University of Nairobi, and I am grateful for the opportunity. I wish to thank my supervisors Prof. Loice Gathece and Prof Arthur Kemoli who were always there to offer guidance and encouragement throughout the process. My sincere appreciation for my family and friends who stood by me even when I had no time for them and especially my children Erick, Aileen, Mbithe and Jynette. -

Veterinary Dentistry Basics

Veterinary Dentistry Basics Introduction This program will guide you, step by step, through the most important features of veterinary dentistry in current best practice. This chapter covers the basics of veterinary dentistry and should enable you to: ü Describe the anatomical components of a tooth and relate it to location and function ü Know the main landmarks important in assessment of dental disease ü Understand tooth numbering and formulae in different species. ã 2002 eMedia Unit RVC 1 of 10 Dental Anatomy Crown The crown is normally covered by enamel and meets the root at an important landmark called the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ). The CEJ is anatomically the neck of the tooth and is not normally visible. Root Teeth may have one or more roots. In those teeth with two or more roots the point where they diverge is called the furcation angle. This can be a bifurcation or a trifurcation. At the end of the root is the apex, which can have a single foramen (humans), a multiple canal delta arrangement (cats and dogs) or remain open as in herbivores. In some herbivores the apex closes eventually (horse) whereas whereas in others it remains open throughout life. The apical area is where nerves, blood vessels and lymphatics travel into the pulp. Alveolar Bone The roots are encased in the alveolar processes of the jaws. The process comprises alveolar bone, trabecular bone and compact bone. The densest bone lines the alveolus and is called the cribriform plate. It may be seen radiographically as a white line called the lamina dura. -

The Development of the Permanent Teeth(

ro o 1Ppr4( SVsT' r&cr( -too c The Development of the Permanent Teeth( CARMEN M. NOLLA, B.S., D.D.S., M.S.* T. is important to every dentist treat- in the mouth of different children, the I ing children to have a good under - majority of the children exhibit some standing of the development of the den- pattern in the sequence of eruption tition. In order to widen one's think- (Klein and Cody) 9 (Lo and Moyers). 1-3 ing about the impingement of develop- However, a consideration of eruption ment on dental problems and perhaps alone makes one cognizant of only one improve one's clinical judgment, a com- phase of the development of the denti- prehensive study of the development of tion. A measure of calcification (matura- the teeth should be most helpful. tion) at different age-levels will provide In the study of child growth and de- a more precise index for determining velopment, it has been pointed out by dental age and will contribute to the various investigators that the develop- concept of the organism as a whole. ment of the dentition has a close cor- In 1939, Pinney2' completed a study relation to some other measures of of the development of the mandibular growth. In the Laboratory School of the teeth, in which he utilized a technic for University of Michigan, the nature of a serial study of radiographs of the same growth and development has been in- individual. It became apparent that a vestigated by serial examination of the similar study should be conducted in same children at yearly intervals, utiliz- order to obtain information about all of ing a set of objective measurements the teeth. -

Morphological Integration in the Hominin Dentition: Evolutionary, Developmental, and Functional Factors

ORIGINAL ARTICLE doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01508.x MORPHOLOGICAL INTEGRATION IN THE HOMININ DENTITION: EVOLUTIONARY, DEVELOPMENTAL, AND FUNCTIONAL FACTORS Aida Gomez-Robles´ 1,2 and P. David Polly3 1Konrad Lorenz Institute for Evolution and Cognition Research, Adolf Lorenz Gasse 2, A-3422 Altenberg, Austria 2E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] 3Department of Geological Sciences, Indiana University, 1001 East 10th Street, Bloomington, Indiana 47405 Received June 29, 2011 Accepted October 19, 2011 As the most common and best preserved remains in the fossil record, teeth are central to our understanding of evolution. However, many evolutionary analyses based on dental traits overlook the constraints that limit dental evolution. These constraints are di- verse, ranging from developmental interactions between the individual elements of a homologous series (the whole dentition) to functional constraints related to occlusion. This study evaluates morphological integration in the hominin dentition and its effect on dental evolution in an extensive sample of Plio- and Pleistocene hominin teeth using geometric morphometrics and phyloge- netic comparative methods. Results reveal that premolars and molars display significant levels of covariation; that integration is stronger in the mandibular dentition than in the maxillary dentition; and that antagonist teeth, especially first molars, are strongly integrated. Results also show an association of morphological integration and evolution. Stasis is observed in elements with strong functional and/or developmental interactions, namely in first molars. Alternatively, directional evolution (and weaker integration) occurs in the elements with marginal roles in occlusion and mastication, probably in response to other direct or indirect selective pressures. -

A Global Compendium of Oral Health

A Global Compendium of Oral Health A Global Compendium of Oral Health: Tooth Eruption and Hard Dental Tissue Anomalies Edited by Morenike Oluwatoyin Folayan A Global Compendium of Oral Health: Tooth Eruption and Hard Dental Tissue Anomalies Edited by Morenike Oluwatoyin Folayan This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Morenike Oluwatoyin Folayan and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-3691-2 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-3691-3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword .................................................................................................. viii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Dental Development: Anthropological Perspectives ................................. 31 Temitope A. Esan and Lynne A. Schepartz Belarus ....................................................................................................... 48 Natallia Shakavets, Alexander Yatzuk, Klavdia Gorbacheva and Nadezhda Chernyavskaya Bangladesh ............................................................................................... -

Allometric Scaling in the Dentition of Primates and Prediction of Body Weight from Tooth Size in Fossils

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 58%-100 (1982) Allometric Scaling in the Dentition of Primates and Prediction of Body Weight From Tooth Size in Fossils PHILIP D. GINGERICH, B. HOLLY SMITH, AND KAREN ROSENBERG Museum of Paleontology (P.D.G.)and Department of Anthropology (B.H.S. and K.R.), The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 KEY WORDS Primate dentition, Allometry, Body size, Adapidae, Hominoidea ABSTRACT Tooth size varies exponentially with body weight in primates. Logarithmic transformation of tooth crown area and body weight yields a linear model of slope 0.67 as an isometric (geometric) baseline for study of dental allometry. This model is compared with that predicted by metabolic scaling (slope = 0.75). Tarsius and other insectivores have larger teeth for their body size than generalized primates do, and they are not included in this analysis. Among generalized primates, tooth size is highly correlated with body size. Correlations of upper and lower cheek teeth with body size range from 0.90-0.97, depending on tooth position. Central cheek teeth (P: and M:) have allometric coefficients ranging from 0.57-0.65, falling well below geometric scaling. Anterior and posterior cheek teeth scale at or above metabolic scaling. Considered individually or as a group, upper cheek teeth scale allometrically with lower coefficients than corresponding lower cheek teeth; the reverse is true for incisors. The sum of crown areas for all upper cheek teeth scales significantly below geometric scaling, while the sum of crown areas for all lower cheek teeth approximates geometric scaling. Tooth size can be used to predict the body weight of generalized fossil primates. -

Initiation to Eruption

Head and Neck embryology Tooth Development Review head and neckblk embryology Initiation to eruption Skip Review Initiation Initiation stomodeum Epithelial cells (dental lamina) During 6th week, ectoderm in stomodeum forms horseshoe shaped mass of oral epithelium mesenchyme Basement membrane mesenchyme Initiation of anterior primary teeth Epithelial cells in horseshoe Dental lamina begins begins the sixth to seventh week form dental lamina growing into mesenchyme of development, initiation of additional At site where tooth will be teeth follows and continues for years Dental Lamina – Initiation Supernumerary tooth PREDICT what would happen if an extra tooth was initiated. Mesiodens 1 Bud Stage – eighth week Bud Stage Epithelium (dental Lamina) Dental lamina grows down into mesenchyme at site of tooth. Mesenchyme starts to change composition in response mesenchyme PREDICT what would happen if two tooth buds fused together or one tooth bud split in half. Fusion/Gemination Cap stage – week 9 By week 9, all germ layers of future tooth have formed ElEnamel organ (ename ll)l only) Dental papilla (dentin and pulp) Fusion Gemination Dental sac (cementum, PDL, Alveolar bone) PREDICT how you would know if it was mesenchyme fusion or gemination Cap Stage Successional Dental Lamina Each primary tooth germ has epithelium a successional lamina that becomes a permanent tooth Succedaneous teeth replace a deciduous tooth, nonsuccedaneous do not IDENTIFY nonsuccedaneous teeth mesenchyme PREDICT What occurs if no successional lamina forms? 2 Congenitally -

QUICK ORAL HEALTH FACTS ABOUT the YOUNG Dr Ng Jing Jing, Dr Wong Mun Loke

ORAL health IN PRIMARY CARE UNIT NO. 2 QUICK ORAL HEALTH FACTS ABOUT THE YOUNG Dr Ng Jing Jing, Dr Wong Mun Loke ABSTRACT Table 1. Eruption sequence of Primary Dentition This article sheds light on the sequence of teeth eruption Primary Upper Teeth Primary Lower Teeth in the young and teething problems; highlights the importance and functions of the primary dentition and Central Incisors: 8-13 months Central Incisors: 6-10 months provides a quick overview of common developmental Lateral Incisors: 8-13 months Lateral Incisors: 10-16 months dental anomalies and other dental conditions in Canines: 16-23 months Canines: 16-23 months children. First Molars: 16-23 months First Molars: 13-19 months Second Molars: 25-33 months Second Molars: 23-31 months SFP2011; 37(1) Supplement : 10-13 Table 2. Eruption sequence of Adult Dentition Adult Upper Teeth Adult Lower Teeth INTRODUCTION Central Incisors: 7-8 years Central Incisors: 6-7 years The early years are always full of exciting moments as we observe Lateral Incisors: 8-9 years Lateral Incisors: 7-8 years our children grow and develop. One of the most noticeable Canines: 11-12 years Canines: 9-10 years aspects of their growth and development is the eruption of First Premolars: 10-11 years First Premolars: 10-11 years teeth. The first sign of a tooth in the mouth never fails to Second Premolars: 11-12 years Second Premolars: 11-12 years attract the attention of the parent and child. For the parent, it First Molars: 6-7 years First Molars: 6-7 years marks an important developmental milestone of the child but Second Molars: 12-13 years Second Molars: 11-13 years for the child, it can be a source of irritation brought on by the Third Molars: 18-25 years Third Molars: 18-25 years whole process of teething. -

Development of Human Dentition … with Dental and Orthodontic Considerations

Development of Human Dentition … with dental and orthodontic considerations Prenatal Infancy Early Childhood Childhood Late Childhood Adolescence & Adulthood (First twelve permanent teeth erupt) (Next twelve permanent teeth erupt) (Four twelve year molars erupt) 4 months Birth 18-30 6-7 9-10 12-15 in utero months years years years 6 months 4-8 2-3 7-8 10-11 21 in utero months years years years years 1. Anomalies in primary tooth 8-12 3-4 8-9 11-12 1. Trauma to the permanent dentition may cause A. Number C. Proportion months years years complications such as: B. Size D. Shape years A. Ankylosis C. Altered occlusion 2. Amelogenesis Impfecta of primary dentition B. Necrosis D. Reinforce sports mouthguard 3. Enamel Hypoplasia 2. Piercings 4. Cleft palate/lip development A. Source of infections B. Tooth fractures 5. Tetracycline Staining of primary teeth 3. TIME FOR COMPREHENSIVE, PHASE 2, AND LIMITED ORTHODONTICS 4. INVISALIGN 1. Untreated decay of primary dentition may cause 1. After age 8yrs, tetracycline antibiotics is not 9-15 4-5 5. Third Molars (Wisdom Teeth) typically evaluated months years complications to the permanent dentition contraindicated A. Enamel hypoplasia B. Space loss 2. Trauma to the permanent dentition may cause 2. TIME FOR INTERCEPTIVE AND PHASE 1 complications such as: ORTHODONTICS A. Ankylosis C. Altered occlusion B. Necrosis D. Reinforce sports mouthguard 3. IN BETWEEN PHASE 1 AND PHASE 2 ORTHODONTICS 4. TIME FOR COMPREHENSIVE ORTHODONTICS 15-21 5-6 months years “Get A Great Smile For Life.” DANIEL J. GROB, D.D.S., M.S.