Chapter 4: the Fetish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maid to Order: Commercial Fetishism and Gender Power

Maid to Order COMMERCIALFETISHISM AND GENDERPOWER In Sex, Madonna has her wits, if not her clothes, about her. The scandal Anne McClintock of Sex is the scandal of S/M: the provocative confession that the edicts of power are reversible. So the critics bay for her blood: a woman who takes sex and money into her own hands must-sooner or later-bare her breast to the knife. But with the utmost artifice and levity, Madonna refuses to imitate tragedy. Taking sex into the street, and money into the bedroom, she flagrantly violates the sacramental edicts of private and public, and stages sexual commerce as a theater of transformation. Madonna's erotic photo album is filled with the theatrical parapher- nalia of S/M: boots, chains, leather, whips, masks, costumes, and scripts. Andrew Neil, editor of the Sunday Times, warns ominously that it thus runs the risk of unleashing "the dark side" of human nature, "with par- ticular danger for women."1 But the outrage of Sex is its insight into con- sensual S/M as high theater.2 Demonizing S/M confuses the distinction between unbridled sadism and the social subculture of consensual fetishism.3 To argue that in consensual S/M the "dominant" has power, and the slave has not, is to read theater for reality; it is to play the world forward. The economy of S/M is the economy of conversion: slave to master, adult to baby, pain to pleasure, man to woman, and back again. S/M, as Foucault puts it, "is not a name given to a practice as old as Eros; it is a massive cultural fact which appeared precisely at the end of the eighteenth century, and which constitutes one of the greatest conver- sions of Western imagination: unreason transformed into delirium of the heart."4 Consensual S/M "plays the world backwards."5 In Sex, as in S/M, roles are swiftly swapped. -

2020-05-25 Prohibited Words List

Clouthub Prohibited Word List Our prohibited words include derogatory racial terms and graphic sexual terms. Rev. 05/25/2020 Words Code 2g1c 1 4r5e 1 1 Not Allowed a2m 1 a54 1 a55 1 acrotomophilia 1 anal 1 analprobe 1 anilingus 1 ass-fucker 1 ass-hat 1 ass-jabber 1 ass-pirate 1 assbag 1 assbandit 1 assbang 1 assbanged 1 assbanger 1 assbangs 1 assbite 1 asscock 1 asscracker 1 assface 1 assfaces 1 assfuck 1 assfucker 1 assfukka 1 assgoblin 1 asshat 1 asshead 1 asshopper 1 assjacker 1 asslick 1 asslicker 1 assmaster 1 assmonkey 1 assmucus 1 assmunch 1 assmuncher 1 assnigger 1 asspirate 1 assshit 1 asssucker 1 asswad 1 asswipe 1 asswipes 1 autoerotic 1 axwound 1 b17ch 1 b1tch 1 babeland 1 1 Clouthub Prohibited Word List Our prohibited words include derogatory racial terms and graphic sexual terms. Rev. 05/25/2020 ballbag 1 ballsack 1 bampot 1 bangbros 1 bawdy 1 bbw 1 bdsm 1 beaner 1 beaners 1 beardedclam 1 bellend 1 beotch 1 bescumber 1 birdlock 1 blowjob 1 blowjobs 1 blumpkin 1 boiolas 1 bollock 1 bollocks 1 bollok 1 bollox 1 boner 1 boners 1 boong 1 booobs 1 boooobs 1 booooobs 1 booooooobs 1 brotherfucker 1 buceta 1 bugger 1 bukkake 1 bulldyke 1 bumblefuck 1 buncombe 1 butt-pirate 1 buttfuck 1 buttfucka 1 buttfucker 1 butthole 1 buttmuch 1 buttmunch 1 buttplug 1 c-0-c-k 1 c-o-c-k 1 c-u-n-t 1 c.0.c.k 1 c.o.c.k. -

In the Habit of Being Kinky: Practice and Resistance

IN THE HABIT OF BEING KINKY: PRACTICE AND RESISTANCE IN A BDSM COMMUNITY, TEXAS, USA By MISTY NICOLE LUMINAIS A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of Anthropology MAY 2012 © Copyright by MISTY NICOLE LUMINAIS, 2012 All Rights Reserved © Copyright by MISTY NICOLE LUMINAIS, 2012 All rights reserved To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of MISTY NICOLE LUMINAIS find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ___________________________________ Nancy P. McKee, Ph.D., Chair ___________________________________ Jeffrey Ehrenreich, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Faith Lutze, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Jeannette Mageo, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I could have not completed this work without the support of the Cactus kinky community, my advisors, steadfast friends, generous employers, and my family. Members of the kinky community welcomed me with all my quirks and were patient with my incessant questions. I will always value their strength and kindness. Members of the kinky community dared me to be fully present as a complete person rather than relying on just being a researcher. They stretched my imagination and did not let my theories go uncontested. Lively debates and embodied practices forced me to consider the many paths to truth. As every anthropologist before me, I have learned about both the universality and particularity of human experience. I am amazed. For the sake of confidentiality, I cannot mention specific people or groups, but I hope they know who they are and how much this has meant to me. -

Sexual Fetishes, San Francisco, CA: Digita Consensual Sex; Desire, Sexual; Domination Publications

1 surrogate), and became a foot fetishist. Freud did Fetish not discuss sexual fetishism in women. SUSAN M. BLOCK In a sense, the sexual fetishist “worships” the The Dr. Susan Block Institute for the Erotic Arts & sexual fetish object much like the traditional Sciences, Los Angeles, California, United States fetishist venerates a totem pole of deities or a superstitious person invests magical powers in a rabbit’s foot or other lucky charm. The main dif- The word fetish derives from the French fétiche, ference is that the erotic fetishist combines sexual which comes from the Portuguese feitiço (“spell”), activity and fantasy with the mystical adoration of which in turn stems from the Latin facticius the fetish object or activity (Love 1994:109–111). (“artificial”) and facere (“to make”). In traditional, spiritual terms, a fetish is an object, such as a bone, a piece of fur, a statue carved in the likeness Childhood and adolescence origins of a deity, or a Christian cross, believed to possess mystical energy. In the classic sense, the sexual fetishist requires the fetish object—or at least, some kind of fantasy of the fetish object—in order to have sex. Some Sexual fetish psychologists call this strong, deep-seated, some- times compulsive need a “paraphilia.” The male The terms “erotic fetish” and “sexual fetish” were fetishist requires the fetish object to get an erec- first introduced by nineteenth-century French tion; he cannot get excited without it, and he may psychologist and inventor of the first usable intel- become obsessed with it. For the human female, ligence test, Alfred Binet (1887), who proposed sexual arousal and fetishism are a little more mys- that fetishes be classified as either “spiritual” or terious and difficult to pinpoint. -

CDR's Kink Interest & Willingness Inventory

Name ___________________________ 1 CDR’s Kink Interest & Willingness Inventory Purpose: This inventory is designed to help facilitate communication between you and your partner about your kink and sexual interests, desires and curiosities as well as to gauge your willingness to try things outside your own interests if it means pleasing your partner. Directions: 1. Decide if you wish to fill this out as someone taking on the role of a dominant/top, submissive/bottom or (if the role you like to take varies) as a switch. 2. Fill out your copy of this inventory privately. Try not to rush. 3. Set a time to sit down with your partner to exchange inventories, read them and discuss. This should be outside the bedroom, like over coffee, where there is no pressure to immediately try any of the activities. Rate your interest or willingness on a scale of 0 to 3, as a hard limit or unknown: • 0 = I have no interest, but it’s not a hard limit • 1 = I have very little interest or willingness • 2 = I have some interest or willingness • 3 = I am very interested or willing • X = This is a hard limit. I am not willing to do this under any circumstances. • ? = I don’t know what this is. Definitions: “Interested In” is about your desires. It means that you would like, or think you would like, to experience this activity. “Willing To” is about experimenting with or pleasing your partner. It indicates your level of willingness to try something for your partner, regardless of your own level of interest in an activity. -

Fifty Shades of Grey: Implications for Counseling BDSM Clients

Article 13 Fifty Shades of Grey: Implications for Counseling BDSM Clients Melissa N. Freeburg and Melanie J. McNaughton Freeburg, Melissa N., Department of Counselor Education, Bridgewater State University. McNaughton, Melanie J., Department of Communication Studies, Bridgewater State University. Abstract Four primary themes regarding counseling BDSM clients are addressed: popular culture, mental health contexts and the DSM, parallels with now-defunct homosexual paraphilias, and resources for counselors. The authors present an introduction of commonly used BDSM terms based on field research and supported by a case study. Attention is given to challenges BDSM clients face, paraphilic disorder codes used to clinically define BDSM activities, and how diagnostic codes pathologize nontraditional sexuality, which can create a disjunction between counselor education and clients’ lived experiences. This disjunction is emphasized by popularizations of BDSM, such as E. L. James’ Fifty Shades trilogy, which expand social acceptance while also solidifying misrepresentations of the kink lifestyle. Keywords: BDSM, Fifty Shades, paraphilia, nontraditional sexuality, counselor education “Jason” entered into our counseling relationship with a presenting concern of adjusting to his recent separation from his wife of 15 years. He purposefully sought me out as a counselor based on a referral that identified my practice as kink-friendly. Jason admitted that during his marriage he had numerous sexual relationships with women without his wife’s knowledge. He stated that his emotional and physical connection with his wife was strong but that sex was infrequent and too “vanilla” for his liking. He perceived that she would not be open to any kinky activities. To satisfy his interest in exploring the BDSM (an overlapping abbreviation of Bondage and Discipline [BD], Dominance and Submission [DS], Sadism and Masochism [SM]) lifestyle, Jason joined several fetish-based Web sites, which is where he made contact with other women. -

Fifty Shades of Fetishes an Exploration Into Kinks, Fetishes and Where They Come From

(/) (/) Fifty Shades of Fetishes An exploration into kinks, fetishes and where they come from 02/11/15 12:00am | By RACHEL KRAMER (http://www.ubspectrum.com/staff/rachel-kramer) , RACHEL KRAMER (http://www.ubspectrum.com/staff/rachel-kramer) ! (mailto:?subject=Fifty Shades of Fetishes&body=Check out this article http://www.ubspectrum.com/article/2015/02/fifty-shades-of-fetishes) " (http://twitter.com/share?text=Fifty Shades of Fetishes) # (http://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http://www.ubspectrum.com/article/2015/02/fifty- shades-of-fetishes) Brittney is turned on by the sound of urine falling into a toilet. It’s one of her kinks. Lorna Loster has been tying men up since she was 14 years old. It’s her fetish. A fetish is something one needs in order to have a (http://media.bts.s3.amazonaws.com/11452_image54e4bfbf32824f.jpg)fulfilling sexual experience while a kink is just The Spectrum something sexual one enjoys. BDSM, a kinky form of rough sex involving a Although sometimes thought of as taboo or dominant and a submissive, is growing in popularity uncommon, 23.5 percent of UB students admitted and gaining acceptance in main-stream media with to having some sort of kink or fetish including the release of Fifty Shades of Grey. Some students, spanking, public sex, feet and bondage in The however, still struggle to accept their own kinks or Spectrum’s sex survey. fetishes. Yusong Shi, The Spectrum Brittney, whose name has been changed for her privacy, is aroused by urine-related activities. This kink is also defined as urolangi, or “watersports,” including watching people urinate, getting urinated on – a “golden shower” – or watching people wet themselves. -

Nazi Uniform Fetish and Role Playing: a Subculture of Erotic Evil

Nazi Uniform Fetish and Role Playing: A Subculture of Erotic Evil The word "Nazi" typically evokes thoughts of Anti-Semitism, war crimes, and the Holocaust. To be sure, war crimes and genocide were committed by some Nazis and this research is not meant as a defense of, or being in support of, those activities. Nor is this work an endorsement of the ideologies and activities of supremacist groups. Rather, this study is an empirical work on Nazi fetish and role playing as an active and ongoing component within the bondage, discipline/dominance, and sadomasochism (BDSM) subculture. An analysis of BDSM subculture is consistent with the discipline of popular culture's examination of "subcultures" and "emergent cultures" (King, 2012, p. 687). In detailing the history of popular culture as a discipline, Calweti (1976, p. 166) writes "popular culture as a phrase symbolizes an attitude ranging between neutrality and enthusiasm for the same kind of cultural products which would have been condemned as garbage by many earlier intellectuals and artists." Scholars (Weinberg, Colin, & Moser, 1984; Weinberg, Williams, & Moser, 1984; Moser & Levitt, 1987; Sandnabba, et al, 2002; Richters, et al, 2008; Stiles & Clark, 2011) have examined this "cultural product" of BDSM and informed us of a vibrant and growing subculture. Such work expands our knowledge of popular culture and the present study accomplishes the same. We do so from a sociological perspective, one of the disciplines used in the analysis of popular culture, a "growth industry in the American academy" (Traube, 1996, p. 127). In their comprehensive account of the analytic tools that have legitimized popular culture as a scholarly interest, Mukeiji and Schudson (1986) note the contribution of Erving Goffinan's work on performances in understanding it as a "key form of cultural behavior." They write, "performance is a kind of activity that is formally staged or an aspect of everyday life in which a person is oriented to and intends to have some effect on an audience" (Mukeiji & Schudson, 1986, p. -

A Dominant's Handbook

A Dominant's Handbook Toy Slaves Brothel Training TSB 11/26/2011 The Joy of Fantasy No matter how pleasant and fulfilling your daily life is, sometimes you need to escape from your role as responsible adult, dutiful worker or dedicated family member. The more stressful that role is, the further it is from your own deepest impulses, the more you need an escape from the limitations of everyday life. Some people use alcohol, drugs, or gambling to transcend their ordinary lives, but these activities generally prove to be both destructive and unsatisfying. But the escape provided by a rich fantasy life can be constructive and extraordinarily fulfilling. Instead of destroying true intimacy, shared fantasy increases it. Instead of harming the body, sexual release helps it. Instead of stifling the needs of your true self, fantasy allows you to express and realize your deepest needs and in the process, fantasy brings forth a new, stronger reality. …… Mistress Lorelei (from The Mistress Manual, the good girl’s guide to female dominance) Page | 2 Table of Contents What is a Dominant ... 5 Rules for Dominants... 6 Your Service at Toys... 7 D/s Interactions... 8 Madame, Masters, Mistresses, Dommes… 9 Your Training at Toys... 11 Promotion... 12 Training the Girls... 13 Punishment... 15 Check rides… 17 D/s Relationships... 21 Just Who's in Charge Here... 22 The Scene… 23 Is It BDSM or Abuse… 30 Linden Age Policy… 34 Roles… 35 Taking Customers/Your Rate… 38 Dominant Boards… 38 Lady Venom's Dictum... 39 Resources... 41 Page | 3 BDSM Etiquette... 43 A Domme's Primer.. -

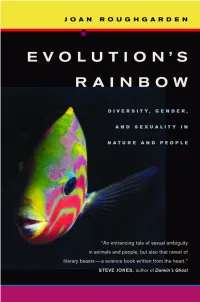

Joan Roughgarden

EVOLUTION’S RAINBOW Evolution’s Rainbow Diversity, Gender, and Sexuality in Nature and People Joan Roughgarden UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles London University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2004 by Joan Roughgarden Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roughgarden, Joan. Evolution’s rainbow : diversity, gender, and sexuality in nature and people / Joan Roughgarden. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-24073-1 1. Biological diversity. 2. Sexual behavior in animals. 3. Gender identity. 4. Sexual orientation. I. Title. qh541.15.b56.r68 2004 305.3—dc22 2003024512 Manufactured in the United States of America 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 10987654 321 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ansi/niso z39.48-1992(R 1997) (Per- manence of Paper). To my sisters on the street To my sisters everywhere To people everywhere Contents Introduction: Diversity Denied / 1 PART ONE ANIMAL RAINBOWS 1 Sex and Diversity / 13 2 Sex versus Gender / 22 3 Sex within Bodies / 30 4 Sex Roles / 43 5 Two-Gender Families / 49 6 Multiple-Gender Families / 75 7 Female Choice / 106 8 Same-Sex Sexuality / 127 9 The Theory of Evolution / 159 PART TWO HUMAN RAINBOWS 10 An Embryonic Narrative / 185 11 Sex Determination / 196 12 Sex Differences / 207 13 Gender Identity / 238 14 Sexual Orientation / 245 15 Psychological Perspectives / 262 16 Disease versus Diversity / 280 17 Genetic Engineering versus Diversity / 306 PART THREE CULTURAL RAINBOWS 18 Two-Spirits, Mahu, and Hijras / 329 19 Transgender in Historical Europe and the Middle East / 352 20 Sexual Relations in Antiquity / 367 21 Tomboi, Vestidas, and Guevedoche / 377 22 Trans Politics in the United States / 387 Appendix: Policy Recommendations / 401 Notes / 409 Index / 461 INTRODUCTION Diversity Denied On a hot, sunny day in June of 1997, I attended my first gay pride pa- rade, in San Francisco. -

From Sadomasochism to BDSM : Rethinking Object Relations Theorizing Through Queer Theory and Sex-Positive Feminism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Smith College: Smith ScholarWorks Smith ScholarWorks Theses, Dissertations, and Projects 2014 From sadomasochism to BDSM : rethinking object relations theorizing through queer theory and sex-positive feminism Simon Z. Weismantel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Weismantel, Simon Z., "From sadomasochism to BDSM : rethinking object relations theorizing through queer theory and sex-positive feminism" (2014). Masters Thesis, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses/825 This Masters Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Projects by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Simon Z. Weismantel From Sadomasochism to BDSM: Rethinking Object Relations Theorizing Through Queer Theory and Sex-Positive Feminism ABSTRACT This theoretical thesis explores the phenomenon of BDSM. BDSM is a type of consensual erotic experience that covers a wide range of interactions between or among people. Referencing the compound acronym BDSM, these interactions encompass: bondage and discipline; dominance and submission; and sadism and masochism. This project investigates psychoanalytic conceptualizations of BDSM, often called sadomasochism in analytic literature. In particular, object relations theory conceptualizations of BDSM are explored. -

Comparing and Contrasting Lifestyle and Professional

COMPARING AND CONTRASTING LIFESTYLE AND PROFESSIONAL DOMINATRICES: A DIVISION BY TRIBUTE Elizabeth Marie Farrington Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Arts in the Department of Sociology, Indiana University September 2017 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Master’s Thesis Committee ______________________________ Robert Aponte Ph.D., Chair ______________________________ Lynn Pike Ph.D. ______________________________ Brian Steensland Ph.D. ii DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this work to my mom. One of the people who has always been there and has always been proud of me. You have helped make me into the woman I am today. You have shown me no matter what my interest is I should not be ashamed I should try to pursue it, unless it is illegal. I love you and thank you for always letting me be me. I would also like to dedicate this work to Dr. Colin Williams. It may come as a surprise, but I aspire to be similar to you someday. I would like to write amazing academic articles about fetishes and deviance. I wish you well and I hope someday you get to read and have only a few edits to make to it. iii ACKNOWLEGMENTS I have many people to acknowledge that helped me during the writing of this thesis. First I would like to acknowledge the women who introduced me to the topic and exposed me to the conflict online. For their protection I will not say their names, but if you ever talked to me when I worked at Lovers’ Lane about BDSM you are included in this.