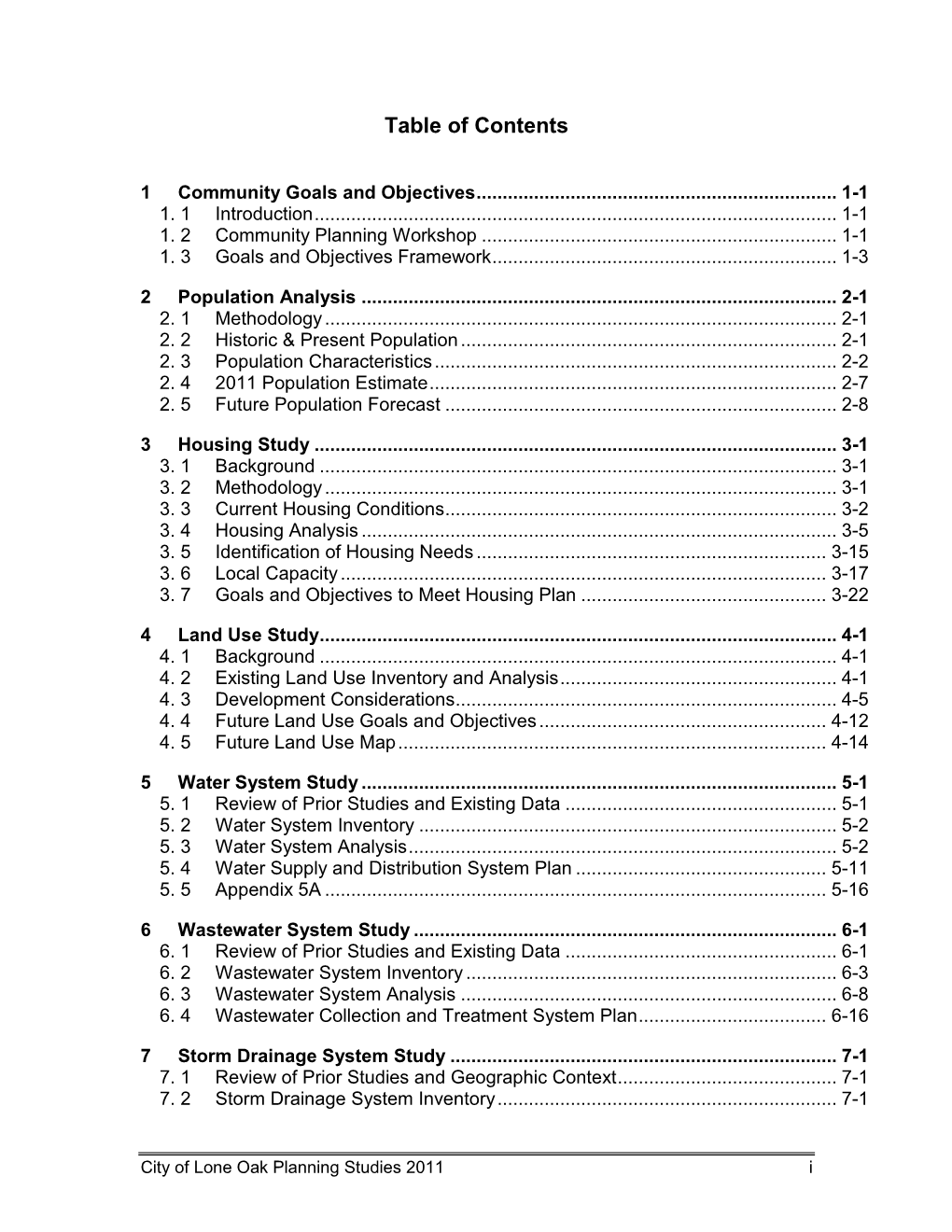

Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part 107 Drone Certificate Study Guide

Part 107 Drone Certificate Study Guide Paul Aitken with Rob Burdick & Tim Ray COPYRIGHT © 2017 Drone U All rights reserved worldwide. Part 107 Drone Certificate Study Guide ISBN: 978-1543057645 INTERIOR DESIGN BY Tim Ray 2 Disclaimer While Drone U has put forth its best efforts in preparing and arranging this study guide, they make no representations or guarantees with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this study guide, and specifically disclaim any implied guarantees that the reader would pass any tests associated with the Part 107 Drone Certificate or any others. Hold Harmless This study guide for the Part 107 Certification was carefully researched, compiled and produced by Drone U utilizing the documents (and links) listed immediately below. With the 107 test outline released by the FAA as our guide, we poured through the over 2,500 pages of content in an effort to break it down for you into this summarized study guide. Therefore, we believe this guide contains the most important, relevant items you need to know as you study for your 107 test. It helps you understand more clearly what you must know, what you should know and even what you don’t need to know. However, by obtaining this guide, you agree to hold harmless Drone U and its subsidiaries from any items missing or unintentionally left out that may be ultimately included on the FAA Part 107 Drone Certificate Test from the below FAA provided resources. FAA - H - 8083 -25B Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge: AC 107 -2 Part 107 Part 107 Summary FAA - H - 8083- 2 (Risk Management Handbook) SIDA 1198 14 CFR 107 150/5200-32B SAFO 09013 SAFO 10017 SAFO 10015 SAFO 15010 FAA AIM AC 006B 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. -

50Th Anniversary of Amelia Earhart's Solo Atlantic Flight

Volume 9 Number 4 May 1982 50th anniversary of Amelia Earhart’s solo Atlantic flight 50th Anniversary of Amelia Earhart’s Schedule of Activities Solo Flight across the Atlantic. Thursday, May 20 Fly-in: Transportation available from Atchison May 20 - 21 - 22 Airport or from Kansas City International (If transportation is needed, let us know YOU CANT MISS ATCHISON THIS YEAR! It is surrounded by arrows flight arrival time at KC Int’l. when making from the North, East, South and West, all pointing to the A.E. Airport. This is reservations). the first airmarking project that encompasses a town from all points of the Sundown: Welcome Party compass. And to put the frosting (there is plenty of it in winter Kansas) on the airport, the beautiful 99 compass rose has been painted on the apron. Friday, May 21 After extensive flying and consultations, the sites were picked by Joan and Morning: Unveiling of AE Plaque at City Hall Joe Reindl. Marie Christensen coordinated the details for the big paint job, Throughout the day: April 3-4. Loyal 99 rollers and brushers from surrounding states participated, Tours of Museum and were rewarded with a barbecue in theMidwest Solvents’ hangar. It was all Visit AE Statue on Mall designed in honor of Blanche Noyes who was always such a part of the 99s’ Visit AE birthplace (time to be announced) activities in Atchison since our first Flyaway in 1963 celebrating the issuance 6:30 p.m. Banquet of the Amelia Earhart 84 Commemorative Airmail stamp. Blanche won’t be with us this year, but looking down from her Cloud Nine, she will know we Saturday, May 22 have been thinking about her. -

People Mover

DEPARTMENT OF AVIATION Gulfstream Aerospace Corporation New Ground Lease Proposal at Love Field Briefing to the Economic Development and Housing Committee June 4, 2007 1 Gulfstream Gulfstream Aerospace Corporation Wholly owned subsidiary of General Dynamics General Dynamics revenues rose to $24 billion in 2006, a 14.7 percent increase over 2005* Gulfstream revenues rose 20 percent to $4.1 billion in 2006* Gulfstream designs, develops, manufactures, markets, services and supports advanced business-jet aircraft Delivered 113 “green” aircraft (w/o interior and paint) in 2006, a 27% increase* *General Dynamics 2006 Annual Shareholders Report 2 Gulfstream Gulfstream Aerospace Corporation Types of aircraft: G150, G200, G350, G450, G500, and G550 With seating capacities of 6-19 passengers Employment 7,900 employees at 7 major locations Dallas Love Field Facility Final Phase Manufacturing (interior and painting) 55 new aircraft projected for 2007, which is a 206% increase since 2003 (G150** and G200**) Provide customer services to over 2,000 aircraft annually that are currently in operation 757 employees currently at Dallas location $26 per hour - average employee wages **See pictures next two pages 3 Gulfstream G150 – Completed at Dallas Love Field Staff recommends approval of the Gulfstream proposal With approval of this lease Gulfstream’s capital commitment at Love Field will be $15 - $35 million Approval of this lease will convert a non-aviation use property into an aviation use property with airside access Approval of this lease will add approximately $85,300 annual revenue to the City NEXT STEPS June 4, 2007 - Economic Development and Housing Committee June 11, 2007 - Transportation and Environment Committee June 27, 2007 - Council Agenda 4 Gulfstream G200 – Completed at Dallas Love Field 5 History of Negotiations July 2006 - Local Gulfstream management and Aviation Dept staff exchanged proposals for new ground lease and hangar development. -

City of Denton Meeting Notice and Agenda Airport Advisory Board

CITY OF DENTON MEETING NOTICE AND AGENDA AIRPORT ADVISORY BOARD Wednesday, April 11, 2018, 5:30 p.m. Denton Enterprise Airport Terminal Meeting Room 5000 Airport Road, Denton, Texas AIRPORT ADVISORY BOARD Robert Tickner, Chairman Sandra Chandler Robert Ismert, Vice Chairman Micah Hope Martin Mainja Ed Ahrens Pete Lane After determining that a quorum is present, the Airport Advisory Board of the City of Denton, Texas will convene in a Regular Meeting during which the following items will be considered: PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE A. U.S. Flag B. Texas Flag “Honor the Texas Flag – I pledge allegiance to thee, Texas, one state under God, one and indivisible.” Presentations from Members of the Public Citizens may complete one Request to Speak “Public Comment” card per night for the “Presentation from Member of the Public” part of the meeting and submit it to the Airport Staff. Presentation from Members of the Public time is reserved for citizen comment regarding non-agendized items. No official action can be taken on these items. Presentation from Members of the Public is limited to five speakers per meeting with each speaker allowed a maximum of three (3) minutes. Airport Manager’s Report The public body may not propose, discuss, deliberate or take legal action on any matter in the summary unless the specific matter is properly noticed for legal action. Under Section 551.042 of the Texas open meetings act, response to citizen comments during the Public Comment time is limited to response to inquiries from the Airport Advisory Board or the public -

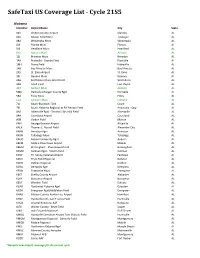

Safetaxi US Coverage List - Cycle 21S5

SafeTaxi US Coverage List - Cycle 21S5 Alabama Identifier Airport Name City State 02A Chilton County Airport Clanton AL 06A Moton Field Muni Tuskegee AL 08A Wetumpka Muni Wetumpka AL 0J4 Florala Muni Florala AL 0J6 Headland Muni Headland AL 0R1 Atmore Muni Atmore AL 12J Brewton Muni Brewton AL 1A9 Prattville - Grouby Field Prattville AL 1M4 Posey Field Haleyville AL 1R8 Bay Minette Muni Bay Minette AL 2R5 St. Elmo Airport St. Elmo AL 33J Geneva Muni Geneva AL 4A6 Scottsboro Muni-Word Field Scottsboro AL 4A9 Isbell Field Fort Payne AL 4R3 Jackson Muni Jackson AL 5M0 Hartselle-Morgan County Rgnl Hartselle AL 5R4 Foley Muni Foley AL 61A Camden Muni Camden AL 71J Ozark-Blackwell Field Ozark AL 79J South Alabama Regional at Bill Benton Field Andalusia - Opp AL 8A0 Albertville Rgnl - Thomas J Brumlik Field Albertville AL 9A4 Courtland Airport Courtland AL A08 Vaiden Field Marion AL KAIV George Downer Airport Aliceville AL KALX Thomas C. Russell Field Alexander City AL KANB Anniston Rgnl Anniston AL KASN Talladega Muni Talladega AL KAUO Auburn University Rgnl Auburn AL KBFM Mobile Downtown Airport Mobile AL KBHM Birmingham - Shuttlesworth Intl Birmingham AL KCMD Cullman Rgnl - Folsom Field Cullman AL KCQF H L Sonny Callahan Airport Fairhope AL KDCU Pryor Field Regional Decatur AL KDHN Dothan Regional Dothan AL KDYA Dempolis Rgnl Dempolis AL KEDN Enterprise Muni Enterprise AL KEET Shelby County Airport Alabaster AL KEKY Bessemer Airport Bessemer AL KEUF Weedon Field Eufaula AL KGAD Northeast Alabama Rgnl Gadsden AL KGZH Evergreen Rgnl/Middleton -

KODY LOTNISK ICAO Niniejsze Zestawienie Zawiera 8372 Kody Lotnisk

KODY LOTNISK ICAO Niniejsze zestawienie zawiera 8372 kody lotnisk. Zestawienie uszeregowano: Kod ICAO = Nazwa portu lotniczego = Lokalizacja portu lotniczego AGAF=Afutara Airport=Afutara AGAR=Ulawa Airport=Arona, Ulawa Island AGAT=Uru Harbour=Atoifi, Malaita AGBA=Barakoma Airport=Barakoma AGBT=Batuna Airport=Batuna AGEV=Geva Airport=Geva AGGA=Auki Airport=Auki AGGB=Bellona/Anua Airport=Bellona/Anua AGGC=Choiseul Bay Airport=Choiseul Bay, Taro Island AGGD=Mbambanakira Airport=Mbambanakira AGGE=Balalae Airport=Shortland Island AGGF=Fera/Maringe Airport=Fera Island, Santa Isabel Island AGGG=Honiara FIR=Honiara, Guadalcanal AGGH=Honiara International Airport=Honiara, Guadalcanal AGGI=Babanakira Airport=Babanakira AGGJ=Avu Avu Airport=Avu Avu AGGK=Kirakira Airport=Kirakira AGGL=Santa Cruz/Graciosa Bay/Luova Airport=Santa Cruz/Graciosa Bay/Luova, Santa Cruz Island AGGM=Munda Airport=Munda, New Georgia Island AGGN=Nusatupe Airport=Gizo Island AGGO=Mono Airport=Mono Island AGGP=Marau Sound Airport=Marau Sound AGGQ=Ontong Java Airport=Ontong Java AGGR=Rennell/Tingoa Airport=Rennell/Tingoa, Rennell Island AGGS=Seghe Airport=Seghe AGGT=Santa Anna Airport=Santa Anna AGGU=Marau Airport=Marau AGGV=Suavanao Airport=Suavanao AGGY=Yandina Airport=Yandina AGIN=Isuna Heliport=Isuna AGKG=Kaghau Airport=Kaghau AGKU=Kukudu Airport=Kukudu AGOK=Gatokae Aerodrome=Gatokae AGRC=Ringi Cove Airport=Ringi Cove AGRM=Ramata Airport=Ramata ANYN=Nauru International Airport=Yaren (ICAO code formerly ANAU) AYBK=Buka Airport=Buka AYCH=Chimbu Airport=Kundiawa AYDU=Daru Airport=Daru -

Private Pilot Study Guide Important Information for Seminar Preparation Please Read This Carefully!

AVIATION SEMINARS PRIVATE PILOT STUDY GUIDE IMPORTANT INFORMATION FOR SEMINAR PREPARATION PLEASE READ THIS CAREFULLY! People attending our courses come to class with wide variations of both knowledge and experience – from those who are still waiting to take their first flight lesson, through those who have been ready for their flight tests for years (private or commercial), but haven’t yet completed their FAA knowledge exam. However, our recommendations below are applicable for everyone. The first thing you will discover is that our course manual is intentionally small. Many test preparation guides have 4 or 5 times as many pages, trying to cover much more information than necessary for the FAA Knowledge Exam. We believe that it is important to obtain all of the knowledge about flying that you can. We do not produce this book with the belief that it will contain all the information you need to know as a pilot, but instead wish to provide you with a study guide that is concise and specific to your FAA Exam. We have written the summaries to be as brief as possible while still providing the necessary background to explain the topic and questions. You’ll find that we cover a lot more information and detail in the classroom! Here’s the most effective way to preview this material: First, you will notice that we have bolded and italicized the correct answer to each of the FAA test questions in the book. We’ve learned that it is counterproductive to test yourself by reading a question and its selection of answers without first knowing the correct answer. -

November 1981 Eus 4 Jo Th O N 5

HieSSnBiusOFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL WOMEN PILOTS ASSOCIATION Volume 8 Number 8 ? November 1981 eus 4 jo th o n 5. friend, Marilyn Copeland, Pat was one of the prime motivating factors in collecting all the Beloved Fast International data needed to apply for our organization’s President 501(c)(3) tax exemption. She was also Dies in Utah instrumental in the construction of our Headquarters Building in Oklahoma City Pat McEwen, beloved past international and in the planning and execution of the president of the Ninety-Nines, was building dedication in 1975 that was such a attending the Southwest Section M eeting in smashing success. As Marilyn Copeland Blanche Noyes Utah when she was stricken by a heart says, “With Pat gone, we will all have to attack on September 18, 1981. She was work harder.” Blanche Wilcox Noyes taken to a Salt Lake City hospital where she Pat was active in all phases of aviation. suffered another heart attack and died on She flew the Powder Puff Derby 12 times, Charter Member Blanche Noyes died in September 24, 1981. the Angel Derby 4 times, and participated in her sleep on October 6, 1981. A native of Pat, the mother of seven children, had many other smaller races. She was a part- Cleveland, Ohio, Blanche lived in logged over 5000 hours since learning to fly time flight instructor and an Accident Washington, D .C. where for 35(4 years she in 1960. An extremely active mem ber of the Prevention Counselor. had been head of the FAA’s airmarking Ninety-Nines since joining in 1961, Pat Pat was a role model for many young program on the country’s 80 coast to coast served as chapter chairman and people and an inspiration to everyone who skyways. -

Work Session Agenda 5:00 P.M

City Council Meeting September 22, 2020 Fletcher Warren Civic Center 5501 Business Highway 69 South City Council David L. Dreiling, Mayor Place 1 Jerry Ransom, Mayor Pro Tem Place 2 Al Atkins Place 3 John Turner Place 4 Holly Gotcher Place 5 Brent Money Place 6 Cedric Dean Work Session Agenda 5:00 p.m. 1. Call to Order 2. Items to be Discussed 3. Items on the Regular Agenda of September 22, 2020 4. EXECUTIVE SESSION AS NEEDED FOR AGENDA ITEMS OR EXECUTIVE SESSION ITEMS AS LISTED ON THE REGULAR AGENDA - SECTIONS 551.071, 551.087, 551.072, 551.074,551.089, OR 551.073 5. Adjourn City of Greenville Texas Printed on 9/17/2020 Page 1 of 4 1 City Council Meeting September 22, 2020 Regular Session Agenda 6:00 p.m. 1. Call to Order 2. Invocation Pastor Jesse Pawley, Ridgecrest Baptist Church 3. Pledge of Allegiance 4. Presentations Gold Star Mother’s and Families Day (John Turner, Councilmember Place 3) 5. Citizens to be Heard - Citizens to be Heard are invited to address the Council on topics not already scheduled for a Public Hearing or listed on the agenda. Present your completed “Citizen’s Comment Card” to the City Secretary prior to the meeting. Speakers are limited to 3 minutes and should conduct themselves in a civil manner. The City Council cannot act on items not listed on the agenda in accordance with the Texas Open Meetings Act. Concerns will be addressed by City Staff; they may be placed on a future agenda or addressed by some other course of response. -

Archie 2018 FINAL.Pdf

Welcome 4 Selection Panel 5 Alaskan Region 6 Central Region 8 Eastern Region 10 Great Lakes Region 12 New England Region 14 Northwest Mountain Region 16 Southern Region 20 Southwest Region 22 Western Pacific Region 24 Region X 28 Honorable Mention 30 Welcome As we celebrate the 14th annual Archie League Medal of Safety Awards and the Region X Commitment to Safety Award, we are reminded that our members’ work ensuring that our National Airspace System is safe and efficient is nothing short of heroic. Named after the first air traffic controller, Archie League, this award represents the core function of our membership and profession: using our unique skills, mindset, training, and experience to positively influence the events under our control. Our program honors dedicated men and women who demonstrated the very best examples of skill and professionalism this year. Each of our award winners faced a unique situation in which their ability to think quickly and remain calm under pressure was tested. These 12 events represent our members’ relentless commitment to safety. To our award winners and all our nominees, congratulations on a job well done! And to all of our NATCA members who nominated these deserving individuals, thank you for your commitment to this program and to our profession. Enjoy the banquet! Paul Rinaldi Patricia Gilbert President Executive Vice President 4 WELCOME NATCA members nominate their colleagues to receive the Archie League Medal of Safety. A selection panel chooses award recipients from the nominees in each region. The 2018 Archie League Medal of Safety Awards selection panel included (from left to right) Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA) Chief Executive Officer & Chairman of the Board Jack Pelton, NATCA Director of Safety and Technology Jim Ullmann, and Air Line Pilots Association, Int’l (ALPA) Aviation Safety Chairman Capt. -

![Example of Private Pilot Test Question Bank [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7201/example-of-private-pilot-test-question-bank-pdf-8627201.webp)

Example of Private Pilot Test Question Bank [Pdf]

05/23/2007 Bank: (Private Pilot) Airman Knowledge Test Question Bank The FAA computer-assisted testing system is supported by a series of supplement publications. These publications, available through several aviation publishers, include the graphics, legends, and maps that are needed to successfully respond to certain test items. Use the following URL to download a complete list of associated supplement books: http://av-info.faa.gov/data/computertesting/supplements. pdf 1. H921 PVT The amount of excess load that can be imposed on the wing of an airplane depends upon the A) position of the CG. B) speed of the airplane. C) abruptness at which the load is applied. 2. H921 PVT Which basic flight maneuver increases the load factor on an airplane as compared to straight-and- level flight? A) Climbs. B) Turns. C) Stalls. 3. H921 PVT During an approach to a stall, an increased load factor will cause the airplane to A) stall at a higher airspeed. B) have a tendency to spin. C) be more difficult to control. 4. H921 PVT (Refer to figure 2.) If an airplane weighs 2,300 pounds, what approximate weight would the airplane structure be required to support during a 60° banked turn while maintaining altitude? A) 2,300 pounds. B) 3,400 pounds. C) 4,600 pounds. 5. H911 PVT The term 'angle of attack' is defined as the angle A) between the wing chord line and the relative wind. B) between the airplane's climb angle and the horizon. C) formed by the longitudinal axis of the airplane and the chord line of the wing. -

2004 Comprehensive Plan

COMPREHENSIVE PLAN 2025 ADOPTED April 27th, 2004 Prepared By: Dunkin, Sefko & Associates, Inc. In Cooperation With: The Comprehensive Plan Advisory Committee & City of Greenville Staff CCOOMMPPRREEHHEENNSSIIVVEE PPLLAANN 22002255 AAcckknnoowwlleeddggeemmeennttss The City of Greenville gratefully acknowledges the time and effort of the following individuals for thei r contribution to the successful planning process that has resulted in the completion of this Comprehensive Plan. City Council S teering Committee Members Mayor - Jim Morris Douglas Felps Place 1 - Dan Perkins Kelly Garrett Place 2 - John C. Nelson Jo Ann Hall Place 3 - Wayne Gilmore Gayla Hardaway {Place 4 - Vacant} Gordon Jones Place 5 - Chris Blakemore Dee Kweller Place 6 - Wendy Bigony Diedre Mead John Nelson Planning & Zoning Commission Dan Perkins John E. Scott Place 1 - Roel Martinez Mitzi Thomas Place 2 - George Kroncke, Jr. A.D. “Cleo” Williams Place 3 - A.D. “Cleo” Williams Clay Woods Place 4 - James Owsley Place 5 - Joe Parker, Vice-Chairman Place 6 - Ronnie Houston – Place 6 Place 7 - Fred Thomas – Place 7 Place 8 - Douglas Felps, Chairman Place 9 - Daniel Keeling City Staff Members Philip Sanders, Director of Community Development John Cobb, Director of Parks and Recreation Massoud Ebrahim, P.E., Director of Public Works Dianne Kolb, Executive Secretary for Community Development TTaabbllee ooff CCoonntteennttss CHAPTER 1: BASELINE ANALYSIS A Foundation for Planning 1--1 Background Information 1--3 PLATE 1-1: Greenville’s Relationship to the Region 1-4 SURROUNDING