1Title Pages-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washoku Guidebook(PDF : 3629KB)

和 食 Traditional Dietary Cultures of the Japanese Itadaki-masu WASHOKU - cultures that should be preserved What exactly is WASHOKU? Maybe even Japanese people haven’t thought seriously about it very much. Typical washoku at home is usually comprised of cooked rice, miso soup, some main and side dishes and pickles. A set menu of grilled fish at a downtown diner is also a type of washoku. Recipes using cooked rice as the main ingredient such as curry and rice or sushi should also be considered as a type of washoku. Of course, washoku includes some noodle and mochi dishes. The world of traditional washoku is extensive. In the first place, the term WASHOKU does not refer solely to a dish or a cuisine. For instance, let’s take a look at osechi- ryori, a set of traditional dishes for New Year. The dishes are prepared to celebrate the coming of the new year, and with a wish to be able to spend the coming year soundly and happily. In other words, the religion and the mindset of Japanese people are expressed in osechi-ryori, otoso (rice wine for New Year) and ozohni (soup with mochi), as well as the ambience of the people sitting around the table with these dishes. Food culture has been developed with the background of the natural environment surrounding people and culture that is unique to the country or the region. The Japanese archipelago runs widely north and south, surrounded by sea. 75% of the national land is mountainous areas. Under the monsoonal climate, the four seasons show distinct differences. -

A.R. Reboot Rider World by U/Terravail

A.R. Reboot Rider World By u/terravail The Rider Cinematic Universe Overview/Synopsis 2 Riders In this world 3 Kamen Rider The Origin 3 Shiin Kamen Rider 3 Kamen Rider The First 4 Kamen Rider Icihigo 4 Kamen Rider Nigo 5 Kamen Rider The Next 6 Kamen Rider V3 6 Kamen Rider The Zero 7 Kamen Riderman 7 Kamen Rider The Strongest(?) 8 Kamen Rider Stronger 8 Kamen Rider Tackle 9 Kamen Rider The Sin 10 Kamen Rider Amazon 10 Kamen Rider The Last 11 Kamen Rider ZX 11 Shocker Rider 12 Notes 13 Overview/Synopsis A basic synopsis of this world is that it’s and A.R. version of the reboot rider worlds, allowing the use of the wider cast of Showa Kamen Riders in the Hesei era reboot. This concept document will be used to make a jumpchain once it’s complete as an alternative to the currently being made Reboot Rider Jump. The stories of the wider cast will feature a remix of the overviews of their stories alongside a boring substory to keep in line with the current Reboot Rider Movies. The Rider List below will be split into the movies they would be introduced in. Movies in this universe in order of release: ● Kamen Rider The First ● Kamen Rider The Next ● Kamen Rider The Zero ● Kamen Rider The Origin ● Kamen Rider The Sin ● Kamen Rider The Strongest ● Kamen Rider The Last (Note that “The Sin” would be a miniseries in this universe) The Notes section of this document will contain the “why” of the decisions made in this document and other general information. -

Protoculture Addicts

PA #88 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #88 (Summer 2006) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 25 BASILISK NEWS Overview Character Profiles 8 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) Story Primer 10 Related Products Releases Shinobi: The live-action movie 12 Manga Releases By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 17 Anime & Manga News 32 URUSEI YATSURA An interview with Robert Woodhead MANGA PREVIEW An Introduction By Zac Bertschy & Therron Martin 53 ES: Eternal Sabbath 35 VIZ MEDIA ANIME WORLD An interview with Alvin Lu By Zac Bertschy 73 Convention Guide 78 Interview ANIME STORIES Hitoshi Ariga 80 Making The Band 55 BEWITCHED AGNES 10 Tips from Full Moon on Becoming a Popstar Okusama Wa Maho Shoujo 82 Fantasia Genre Film Festival By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Sample fileKamikaze Girls 58 BLOOD + The Taste Of Tea By Miyako Matsuda & C. Macdonald 84 The Modern Japanese Music Database Part 35: Home Page 19: Triceratops 60 ELEMENTAL GELADE By Miyako Matsuda REVIEWS 63 GALLERY FAKE 86 Books Howl’s Moving Castle Novel By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Le Guide Phénix Du Manga 65 GUN SWORD Love Hina, Novel Vol. 1 By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 87 Live-Action Lorelei 67 KAMICHU! 88 Manga Kamisama Wa Chugakusei 90 Related Products By Miyako Matsuda CD Soundtracks 69 TIDELINE BLUE Otaku Unite! By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 91 Anime More on: www.protoculture-mag.com & www.animenewsnetwork.com 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S PROTOCULTUREPROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]- ADDICTS Over seven years of writing and editing anime reviews, I’ve put a lot of thought into what a Issue #88 (Summer 2006) review should be and should do, as well as what is shouldn’t be and shouldn’t do. -

The Fukushima Nuclear Accident and Crisis Management

e Fukushima Nuclearand Crisis Accident Management e Fukushima The Fukushima Nuclear Accident and Crisis Management — Lessons for Japan-U.S. Alliance Cooperation — — Lessons for Japan-U.S. Alliance Cooperation — — Lessons for Japan-U.S. September, 2012 e Sasakawa Peace Foundation Foreword This report is the culmination of a research project titled ”Assessment: Japan-US Response to the Fukushima Crisis,” which the Sasakawa Peace Foundation launched in July 2011. The accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant that resulted from the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 11, 2011, involved the dispersion and spread of radioactive materials, and thus from both the political and economic perspectives, the accident became not only an issue for Japan itself but also an issue requiring international crisis management. Because nuclear plants can become the target of nuclear terrorism, problems related to such facilities are directly connected to security issues. However, the policymaking of the Japanese government and Japan-US coordination in response to the Fukushima crisis was not implemented smoothly. This research project was premised upon the belief that it is extremely important for the future of the Japan-US relationship to draw lessons from the recent crisis and use that to deepen bilateral cooperation. The objective of this project was thus to review and analyze the lessons that can be drawn from US and Japanese responses to the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, and on the basis of these assessments, to contribute to enhancing the Japan-US alliance’s nuclear crisis management capabilities, including its ability to respond to nuclear terrorism. -

Piracy Or Productivity: Unlawful Practices in Anime Fansubbing

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aaltodoc Publication Archive Aalto-yliopisto Teknillinen korkeakoulu Informaatio- ja luonnontieteiden tiedekunta Tietotekniikan tutkinto-/koulutusohjelma Teemu Mäntylä Piracy or productivity: unlawful practices in anime fansubbing Diplomityö Espoo 3. kesäkuuta 2010 Valvoja: Professori Tapio Takala Ohjaaja: - 2 Abstract Piracy or productivity: unlawful practices in anime fansubbing Over a short period of time, Japanese animation or anime has grown explosively in popularity worldwide. In the United States this growth has been based on copyright infringement, where fans have subtitled anime series and released them as fansubs. In the absence of official releases fansubs have created the current popularity of anime, which companies can now benefit from. From the beginning the companies have tolerated and even encouraged the fan activity, partly because the fans have followed their own rules, intended to stop the distribution of fansubs after official licensing. The work explores the history and current situation of fansubs, and seeks to explain how these practices adopted by fans have arisen, why both fans and companies accept them and act according to them, and whether the situation is sustainable. Keywords: Japanese animation, anime, fansub, copyright, piracy Tiivistelmä Piratismia vai tuottavuutta: laittomat toimintatavat animen fanikäännöksissä Japanilaisen animaation eli animen suosio maailmalla on lyhyessä ajassa kasvanut räjähdysmäisesti. Tämä kasvu on Yhdysvalloissa perustunut tekijänoikeuksien rikkomiseen, missä fanit ovat tekstittäneet animesarjoja itse ja julkaisseet ne fanikäännöksinä. Virallisten julkaisujen puutteessa fanikäännökset ovat luoneet animen nykyisen suosion, jota yhtiöt voivat nyt hyödyntää. Yhtiöt ovat alusta asti sietäneet ja jopa kannustaneet fanien toimia, osaksi koska fanit ovat noudattaneet omia sääntöjään, joiden on tarkoitus estää fanikäännösten levitys virallisen lisensoinnin jälkeen. -

Tesi Di Laurea

Corso di Laurea magistrale in LINGUE E ISTITUZIONI ECONOMICHE E GIURIDICHE DELL’ASIA E DELL’AFRICA MEDITERRANEA [LM4-12] Tesi di Laurea L’arte del silenzio Il simbolismo nel cinema di Shinkai Makoto Relatore Ch. Prof.ssa Roberta Maria Novielli Correlatore Ch. Prof. Davide Giurlando Laureando Carlotta Noè Matricola 838622 Anno Accademico 2016 / 2017 要旨要旨要旨 この論文の目的は新海誠というアニメーターの映画的手法を検討する ことである。近年日本のアニメーション業界に出現した新海誠は、写実的な スタイルで風景肖像を描くことと流麗なアニメーションを創作することと憂 鬱な物語で有名である。特に、この検討は彼の作品の中にある自分自身の人 生、愛情、人間関係の見方を伝えるための記号型言語に集中するつもりであ る。 第一章には新海誠の伝記、フィルモグラフィとその背景にある経験に 焦点を当たっている。 第二章は監督の映画のテーマに着目する。なかでも人は互いに感情を 言い表せないこと、離れていること、そして愛のことが一番大切である。確 かに、彼の映画の物語は愛情を中心に回るにもかかわらず、結局ハッピーエ ンドの映画ではない。換言すれば、新海誠の見方によると、愛は勝つはずで はない。新海誠は別の日本のアニメーターや作家から着想を得ている。その ため、次はそれに関係があるテクニックとスタイルを検討するつもりである。 第三章には新海誠の作品の分析を通して視覚言語と記号型言語が発表 される。一般的な象徴以外に、伝統、神話というふうに、日本文化につなが る具体的なシンボルがある。一方、西洋文化に触れる言及もある。例えば、 音楽や学術研究に言及する。 こうして、新海誠は異なる文化を背景を問わず観客の皆に同じような感情を 感じさせることができる。 最後に、後付けが二つある。第一に、新海誠が演出したテレビコマー シャルとプロモーションビデオが分析する。第二に、新海誠と宮崎駿という アニメーターを比較する。新海誠の芸術様式は日本のアニメーションを革新 したから、“新宮崎”とよく呼ばれている。にもかかわらず、この呼び名を 離れる芸術様式の分野にも、筋の分野にも様々な差がある。特に、宮崎駿の アニメーションに似ている新海誠の「星を追うこども」という映画を検討す る。 1 L’ARTE DEL SILENZIO Il simbolismo nel cinema di Shinkai Makoto 要旨要旨要旨 …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….Pg.1 INTRODUZIONE …………………………………………………………………………………………..Pg.4 CAPITOLO PRIMO: Shinkai Makoto……………………………………………………………………………………………Pg.6 1.1 Shinkai Makoto, animatore per caso 1.2 Filmografia, sinossi e riconoscimenti CAPITOLO SECONDO : L’arte di Shinkai Makoto……………………………………………………………………………..Pg.18 -

Protoculture Addicts #68

Sample file CONTENTS 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ PROTOCULTURE ✾ PRESENTATION ........................................................................................................... 4 STAFF NEWS ANIME & MANGA NEWS: Japan / North America ............................................................... 5, 10 Claude J. Pelletier [CJP] — Publisher / Manager ANIME & MANGA RELEASES ................................................................................................. 6 Martin Ouellette [MO] — Editor-in-Chief PRODUCTS RELEASES ............................................................................................................ 8 Miyako Matsuda [MM] — Editor / Translator NEW RELEASES ..................................................................................................................... 11 Contributing Editors Aaron K. Dawe, Asaka Dawe, Keith Dawe REVIEWS Kevin Lillard, James S. Taylor MODELS: ....................................................................................................................... 33, 39 MANGA: ............................................................................................................................. 40 Layout FESTIVAL: Fantasia 2001 (Anime, Part 2) The Safe House Metropolis ...................................................................................................................... 42 Cover Millenium Actress ........................................................................................................... -

Penggambaran Stereotip Gender Shoujo Manga Pada Tokoh Anime

IR - PERPUSTAKAAN UNIVERSITAS AIRLANGGA BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Manga adalah komik Jepang, di mana salah satu genre-nya adalah shoujo manga, yaitu manga yang dipasarkan kepada sebagian besar perempuan. Mizuki Takahashi (dalam Macwilliams, 2008) berpendapat bahwa shoujo manga adalah hal yang melekat kepada subkultur Jepang yang disebut shoujo bunka, yaitu dunia tertutup dari, oleh, untuk dan tentang perempuan. Shoujo manga sendiri memiliki berberapa pola didalamnya, salah satunya menyangkut mengenai gender. Ninomiya (dalam Choo, 2008: 281) berpendapat bahwa shoujo manga modern lebih cenderung kepada percintaan dengan narasi ‘perempuan pecundang yang mendapatkan pangeran tampan’. Mengimplikasikan bahwa tidak ada pandangan setara perempuan dengan laki-laki. Pada tahun 1970 dan 1980, ada beberapa shoujo manga yang sangat populer dan juga dianggap sebagai sesuatu yang revolusioner, seperti Candy Candy karya Kyoko Mizuki dan The Rose of Versailles karya Riyoko Ikeda. Kedua komik tersebut fokus kepada percintaan, namun hal itu tidak menghapuskan ambisi dari karakter utama, dimana karakter utama dikomik shoujo manga ini memprioritaskan karir mereka (Choo, 2008). Narasi ini 1 SKRIPSI PENGGAMBARAN STEREOTIP GENDER... TARRA TIARANI IR - PERPUSTAKAAN UNIVERSITAS AIRLANGGA 2 merupakan salah satu narasi yang populer pada era 1970, namun narasi ini perlahan menjadi sedikit dan memiliki pergeseran dalam fokusnya. Ada pergeseran dalam dinamika gender di dalam shoujo manga, seperti yang tercermin dari dua judul shoujo manga terkenal yaitu Fruits Basket dan Hana yori Dango. Berbeda dengan The Rose of Versailles, kedua judul ini memiliki penggambaran karakter perempuan yang cukup berbeda. Dalam Fruits Basket dan Hana yori Dango, karakter utama perempuannya adalah seorang yang kuat namun digambarkan sebagai orang yang menyedihkan dan laki-laki yang sangat agresif (Choo, 2008). -

Apatoons.Pdf

San Diego Sampler #3 Summer 2003 APATOONS logo Mark Evanier Cover Michel Gagné 1 Zyzzybalubah! Contents page Fearless Leader 1 Welcome to APATOONS! Bob Miller 1 The Legacy of APATOONS Jim Korkis 4 Who’s Who in APATOONS APATOONers 16 Suspended Animation Special Edition Jim Korkis 8 Duffell's Got a Brand New Bag: San Diego Comicon Version Greg Duffell 3 “C/FO's 26th Anniversary” Fred Patten 1 “The Gummi Bears Sound Off” Bob Miller 4 Assorted Animated Assessments (The Comic-Con Edition) Andrew Leal 10 A Rabbit! Up Here? Mark Mayerson 11 For All the Little People David Brain 1 The View from the Mousehole Special David Gerstein 2 “Sometimes You Don’t Always Progress in the Right Direction” Dewey McGuire 4 Now Here’s a Special Edition We Hope You’ll REALLY Like! Harry McCracken 21 Postcards from Wackyland: Special San Diego Edition Emru Townsend 2 Ehhh .... Confidentially, Doc - I AM A WABBIT!!!!!!! Keith Scott 5 “Slices of History” Eric O. Costello 3 “Disney Does Something Right for Once” Amid Amidi 1 “A Thought on the Powerpuff Girls Movie” Amid Amidi 1 Kelsey Mann Kelsey Mann 6 “Be Careful What You Wish For” Jim Hill 8 “’We All Make Mistakes’” Jim Hill 2 “Getting Just the Right Voices for Hunchback's Gargoyles …” Jim Hill 7 “Animation vs. Industry Politics” Milton Gray 3 “Our Disappearing Cartoon Heritage” Milton Gray 3 “Bob Clampett Remembered” Milton Gray 7 “Coal Black and De Sebben Dwarfs: An Appreciation” Milton Gray 4 “Women in Animation” Milton Gray 3 “Men in Animation” Milton Gray 2 “A New Book About Carl Barks” Milton Gray 1 “Finding KO-KO” Ray Pointer 7 “Ten Tips for Surviving in the Animation Biz” Rob Davies 5 Rob Davies’ Credits List Rob Davies 2 “Pitching and Networking at the Big Shows” Rob Davies 9 Originally published in Animation World Magazine, AWN.com, January 2003, pp. -

ACADEMIC ENCOUNTER the American University in Japan and Korea R

ACADEMIC ENCOUNTER The American University in Japan and Korea r ACADEMIC ENCOUNTER The American University in Japan and Korea By Martin Bronfenbrennet THE FREE PRESS OF GLENCOE, INC. A division of the Crowell-Collier Publishing Co. New York t BUREAU OF SOCIAL AND POLITICAL RESEARCH Michigan State University f East Lansing, Michigan I Copyright@ 1961 BY THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY East Lansing, Michigan Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 61-63703 i t , PREFACE • This study of some 18 American university affiliations with Japanese and Korean institutions is a small part of a larger study of the American university overseas. The larger study l is undertaken by the Institute for Research on Overseas Pro grams at Michigan State University. What is said here about programs in Japan and Korea can be compared with what other staff members of the Institute have saidabout programs in other countries, particularly other Asian countries such as India and !t Indonesia. , Many believe with ex-President Eisenhower that the American university should expand its foreign affiliations as a contribution t to economic and cultural reconstruction and development over seas, and to better international understanding between America and other countries. In this view, university affiliations are an j important type of "people to people" contacts across national boundaries. Others believe that the American university should f concentrate its limited manpower and resources on the domestic job it does best, and reduce the scale of its commitments abroad. Part of the decision (or compromise) between these viewpoints should be based on a knowledge of what the existing international programs are in fact attempting or accomplishing. -

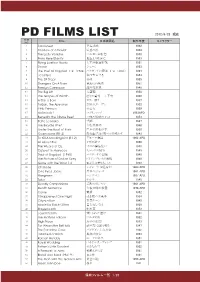

Pd Films List 0824

PD FILMS LIST 2012/8/23 現在 FILM Title 日本映画名 制作年度 キャラクター NO 1 Sabouteur 逃走迷路 1942 2 Shadow of a Doubt 疑惑の影 1943 3 The Lady Vanishe バルカン超特急 1938 4 From Here Etanity 地上より永遠に 1953 5 Flying Leather Necks 太平洋航空作戦 1951 6 Shane シェーン 1953 7 The Thief Of Bagdad 1・2 (1924) バクダッドの盗賊 1・2 (1924) 1924 8 I Confess 私は告白する 1953 9 The 39 Steps 39夜 1935 10 Strangers On A Train 見知らぬ乗客 1951 11 Foreign Correspon 海外特派員 1940 12 The Big Lift 大空輸 1950 13 The Grapes of Wirath 怒りの葡萄 上下有 1940 14 A Star Is Born スター誕生 1937 15 Tarzan, the Ape Man 類猿人ターザン 1932 16 Little Princess 小公女 1939 17 Mclintock! マクリントック 1963APD 18 Beneath the 12Mile Reef 12哩の暗礁の下に 1953 19 PePe Le Moko 望郷 1937 20 The Bicycle Thief 自転車泥棒 1948 21 Under The Roof of Paris 巴里の屋根の根 下 1930 22 Ossenssione (R1.2) 郵便配達は2度ベルを鳴らす 1943 23 To Kill A Mockingbird (R1.2) アラバマ物語 1962 APD 24 All About Eve イヴの総て 1950 25 The Wizard of Oz オズの魔法使い 1939 26 Outpost in Morocco モロッコの城塞 1949 27 Thief of Bagdad (1940) バクダッドの盗賊 1940 28 The Picture of Dorian Grey ドリアングレイの肖像 1949 29 Gone with the Wind 1.2 風と共に去りぬ 1.2 1939 30 Charade シャレード(2種有り) 1963 APD 31 One Eyed Jacks 片目のジャック 1961 APD 32 Hangmen ハングマン 1987 APD 33 Tulsa タルサ 1949 34 Deadly Companions 荒野のガンマン 1961 APD 35 Death Sentence 午後10時の殺意 1974 APD 36 Carrie 黄昏 1952 37 It Happened One Night 或る夜の出来事 1934 38 Cityzen Ken 市民ケーン 1945 39 Made for Each Other 貴方なしでは 1939 40 Stagecoach 駅馬車 1952 41 Jeux Interdits 禁じられた遊び 1941 42 The Maltese Falcon マルタの鷹 1952 43 High Noon 真昼の決闘 1943 44 For Whom the Bell tolls 誰が為に鐘は鳴る 1947 45 The Paradine Case パラダイン夫人の恋 1942 46 I Married a Witch 奥様は魔女 -

Continuing Education Catalog

l. TurnOver aNew Leaf University of Colorado at Boulder Continuing Education Falll989 Schedule of Courses, Seminars and Workshops t\'11\~ou can earn'""I"'"'' academic credit at e'IC<'J \e""\, high school mrough graduate school. Credit programs include: sou\det E"ening Credit Classes . For un\'ers\t'i course' atcon'en,ent even'nll hour> Independentindependent StudY studY ptogtaD's by corresJ>Ondence and ind\,;dua\ized .msu,,cuon . \e \S -youcente' \earn {or at home.M•anced Ttaininll in Eng;neer\ng and con>P" t er S c,en«· {Ct\'fECS).Earn a )>lasi<TS degree or graduate credit w\lh courses"'\ •"'"'· d r'"" tJo )'our worksite. '"""'''""'' f.\\\\l\\&l\\\1\\\: t1\'\\\\&atl'\'o po\tsh your si<i\\s '""I"'"'' or acquire neW one.' enhance your current career or e><p\ore another [,eld, eont\nu\nil Educauon offers a full spectrUm of pro grams. )>lost classes offer continu\nll f,ducatio~ Un'ts (CEUs),_lhenabonal standard for recording universil)'-\ev<\ noncred'' course parh<'pauon Or earn an t\chievement Certificate in: commercialeonwuter .<pp\\cat\oOS Design and Computer Graphics ~anagement Development \llf\\\\\1 fll' \1'""'"1' s St\1: 'fhe broad ranll• of noncredit course.' offered at con••~'C"' evening and . tto\\&"''"'weekend bouTS mean t""""' no tests, no grades, and no prerequ>S'tes- ~et noncred'' courses. enco,;,passinll bolh personal and prof~sional interests. are taught bY highlY qual\f\ed inStrUc\oTS- Eni<>Y non-comP•"""' \earnmll w,\h o\heTS who share -your interests. t\\l\\11p\eaSC \et us """ know.