Method 9060A: Total Organic Carbon, Part of Test Methods for Evaluating

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Total Organic Carbon (TOC) Guidance Manual

September 2002 RG-379 (Revised) Total Organic Carbon (TOC) Guidance Manual Water Supply Division printed on recycled paper TEXAS COMMISSION ON ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY Total Organic Carbon (TOC) Guidance Manual Prepared by Water Supply Division RG-379 (Revised) September 2002 Robert J. Huston, Chairman R. B. “Ralph” Marquez, Commissioner Kathleen Hartnett White, Commissioner Jeffrey A. Saitas, Executive Director Authorization to use or reproduce any original material contained in this publication—that is, not obtained from other sources—is freely granted. The commission would appreciate acknowledgment. Copies of this publication are available for public use through the Texas State Library, other state depository libraries, and the TCEQ Library, in compli- ance with state depository law. For more information on TCEQ publications call 512/239-0028 or visit our Web site at: www.tceq.state.tx.us/publications Published and distributed by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality PO Box 13087 Austin TX 78711-3087 The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality was formerly called the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission. The TCEQ is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer. The agency does not allow discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, disability, age, sexual orientation or veteran status. In compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, this document may be requested in alternate formats by contacting the TCEQ at 512/239-0028, Fax 239-4488, or 1-800-RELAY-TX (TDD), or by writing -

Estimation of Atmospheric Total Organic Carbon (TOC) – Paving The

Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-2018-1055 Manuscript under review for journal Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discussion started: 12 October 2018 c Author(s) 2018. CC BY 4.0 License. Estimation of atmospheric total organic carbon (TOC) – paving the path towards carbon budget closure Mingxi Yang1*, Zoë L. Fleming2& 5 1 Plymouth Marine Laboratory, Plymouth, United Kingdom 2 National Centre for Atmospheric Science (NCAS), Department of Chemistry, University of Leicester, UK, United Kingdom * Correspondence to M. Yang ([email protected]) & Now at Center for Climate and Resilience Research (CR2), Departamento de Geofísica, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile 10 Abstract. The atmosphere contains a rich variety of reactive organic compounds, including gaseous volatile organic carbon (VOCs), carbonaceous aerosols, and other organic compounds at varying volatility. Here we present measurements of atmospheric non-methane total organic carbon plus carbon monoxide (TOC+CO) during August-September 2016 from a coastal 15 city in the southwest United Kingdom. TOC+CO was substantially elevated during the day on weekdays (occasionally over 2 ppm C) as a result of local anthropogenic activity. On weekends and holidays, with a mean (standard error) of 102 (8) ppb C, TOC+CO was lower and showed much less diurnal variability. Excluding weekday daytime, TOC+CO was significantly lower when winds were coming off the Atlantic Ocean than when winds were coming off land. By subtracting the estimated CO from TOC+CO, we constrain the mean (uncertainty) TOC in marine air to be around 19 (±≥8) ppb C during this period. A proton- 20 transfer-reaction mass spectrometer (PTR-MS) was deployed at the same time, detecting a large range of organic compounds (oxygenated VOCs, biogenic VOCs, aromatics, dimethyl sulfide). -

E.’S Responses ~(Continued)

: I’able K-3. ,Scnping stat~nts and EIS sectimns or .~E.’s responses ~(continued) COnunent scoping nuinber :Stateilmnt topic EIS section or DOE comnt h at this tti want to reiter&e that the Enviro~ntal l~act Statement should not represent. a legalistic charade ..but a sin. cere commitment to seek and evaluate pertinent in for~t ion. Obviously, any Envirocnnental. Assemnt- which led to the Find- ing of No Significant .l~act needs to be reviewed, evaluated and expanded upon, with full regard to the in~t of a broad range of interests, incl”di”g state agenciea,. the: academic comunit y, public interest groups, and private c iti-zens. We muld like to offer some co-”ts: on the in format io” euppl=ied by 00E relative to the probable contents. of the EIS. In the category of production alternatives: : It wuld seem L Need .Section 1.1 ., important tO. re-evaluate the ,need for i~reased protict ion,~nd %e Commnt D1 make every attempt to ::scale dom those need8. It is ine8ca~ able that the quest ion. af the.,need .to prodca plutoniun ia part of the greater ongoing natic,”al.?security debate. If it is indeed. essential that plutoniun: probct ion be stepped up, the Alternatives Saction 2.1 viable? alternatives should be thoroughly explored in the EIS. In the category of socioeconamics: A broad consideration of %cioeconomic .%ction 5.2.1 the state needs to be incorporated, beyond the immdiate jobs effects :-at SiU during construction and as .an ongoing operation. South Carolina has trenmndous potential for no-nuclear economic. -

Carbon Dynamics of Subtropical Wetland Communities in South Florida DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Require

Carbon Dynamics of Subtropical Wetland Communities in South Florida DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jorge Andres Villa Betancur Graduate Program in Environmental Science The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: William J. Mitsch, Co-advisor Gil Bohrer, Co-advisor James Bauer Jay Martin Copyrighted by Jorge Andres Villa Betancur 2014 Abstract Emission and uptake of greenhouse gases and the production and transport of dissolved organic matter in different wetland plant communities are key wetland functions determining two important ecosystem services, climate regulation and nutrient cycling. The objective of this dissertation was to study the variation of methane emissions, carbon sequestration and exports of dissolved organic carbon in wetland plant communities of a subtropical climate in south Florida. The plant communities selected for the study of methane emissions and carbon sequestration were located in a natural wetland landscape and corresponded to a gradient of inundation duration. Going from the wettest to the driest conditions, the communities were designated as: deep slough, bald cypress, wet prairie, pond cypress and hydric pine flatwood. In the first methane emissions study, non-steady-state rigid chambers were deployed at each community sequentially at three different times of the day during a 24- month period. Methane fluxes from the different communities did not show a discernible daily pattern, in contrast to a marked increase in seasonal emissions during inundation. All communities acted at times as temporary sinks for methane, but overall were net -2 -1 sources. Median and mean + standard error fluxes in g CH4-C.m .d were higher in the deep slough (11 and 56.2 + 22.1), followed by the wet prairie (9.01 and 53.3 + 26.6), bald cypress (3.31 and 5.54 + 2.51) and pond cypress (1.49, 4.55 + 3.35) communities. -

CO2-Fixing One-Carbon Metabolism in a Cellulose-Degrading Bacterium

CO2-fixing one-carbon metabolism in a cellulose- degrading bacterium Clostridium thermocellum Wei Xionga, Paul P. Linb, Lauren Magnussona, Lisa Warnerc, James C. Liaob,d, Pin-Ching Manessa,1, and Katherine J. Choua,1 aBiosciences Center, National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Golden, CO 80401; bDepartment of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095; cNational Bioenergy Center, National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Golden, CO 80401; and dAcademia Sinica, Taipei City, Taiwan 115 Edited by Lonnie O. Ingram, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, and approved September 23, 2016 (received for review April 6, 2016) Clostridium thermocellum can ferment cellulosic biomass to for- proposed pathway involving CO2 utilization in C. thermocellum is mate and other end products, including CO2. This organism lacks the malate shunt and its variant pathway (7, 14), in which CO2 is formate dehydrogenase (Fdh), which catalyzes the reduction of first incorporated by phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) 13 CO2 to formate. However, feeding the bacterium C-bicarbonate to form oxaloacetate and then is released either by malic enzyme or and cellobiose followed by NMR analysis showed the production via oxaloacetate decarboxylase complex, yielding pyruvate. How- of 13C-formate in C. thermocellum culture, indicating the presence ever, other pathways capable of carbon fixation may also exist but of an uncharacterized pathway capable of converting CO2 to for- remain uncharacterized. mate. Combining genomic and experimental data, we demon- In recent years, isotopic tracer experiments followed by mass strated that the conversion of CO2 to formate serves as a CO2 spectrometry (MS) (15, 16) or NMR measurements (17) have entry point into the reductive one-carbon (C1) metabolism, and emerged as powerful tools for metabolic analysis. -

Determining the Fraction of Organic Carbon RISC Nondefault Option

Indiana Department of Environmental Management Office of Land Quality 100 N. Senate Indianapolis, IN 46204-2251 GUIDANCE OLQ PH: (317) 232-8941 Indiana Department of Environmental Management Office of Land Quality Determining the Fraction of Organic Carbon RISC Nondefault Option Background Soil can be a complex mixture of mineral-derived compounds and organic matter. The ratios of each component can vary widely depending on the type of soil being investigated. Soil organic matter is a term used by agronomists for the total organic portion of the soil and is derived from decomposed plant matter, microorganisms, and animal residues. The decomposition process can create complex high molecular weight biopolymers (e.g., humic acid) as well as simpler organic compounds (decomposed lignin or cellulose). Only the simpler organic compounds contribute to the fraction of organic carbon. There is not a rigorous definition of the fraction of organic carbon (Foc). However, it can be thought of as the portion of the organic matter that is available to adsorb the organic contaminants of concern. The higher the organic carbon content, the more organic chemicals may be adsorbed to the soil and the less of those chemicals will be available to leach to the ground water. A nondefault option in the Risk Integrated System of Closure (RISC) is to use Foc in the Soil to Ground Water Partitioning Model to calculate a site specific migration to ground water closure level. In the Soil to Ground Water Partition Model, the coefficient, Kd, for organic compounds is the Foc multiplied by the chemical-specific soil organic carbon water partition coefficient, Koc. -

B.-Gioli -Co2-Fluxes-In-Florance.Pdf

Environmental Pollution 164 (2012) 125e131 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Environmental Pollution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/envpol Methane and carbon dioxide fluxes and source partitioning in urban areas: The case study of Florence, Italy B. Gioli a,*, P. Toscano a, E. Lugato a, A. Matese a, F. Miglietta a,b, A. Zaldei a, F.P. Vaccari a a Institute of Biometeorology (IBIMET e CNR), Via G.Caproni 8, 50145 Firenze, Italy b FoxLab, Edmund Mach Foundation, Via E. Mach 1, San Michele all’Adige, Trento, Italy article info abstract Article history: Long-term fluxes of CO2, and combined short-term fluxes of CH4 and CO2 were measured with the eddy Received 15 September 2011 covariance technique in the city centre of Florence. CO2 long-term weekly fluxes exhibit a high Received in revised form seasonality, ranging from 39 to 172% of the mean annual value in summer and winter respectively, while 12 January 2012 CH fluxes are relevant and don’t exhibit temporal variability. Contribution of road traffic and domestic Accepted 14 January 2012 4 heating has been estimated through multi-regression models combined with inventorial traffic and CH4 consumption data, revealing that heating accounts for more than 80% of observed CO2 fluxes. Those two Keywords: components are instead responsible for only 14% of observed CH4 fluxes, while the major residual part is Eddy covariance fl Methane fluxes likely dominated by gas network leakages. CH4 uxes expressed as CO2 equivalent represent about 8% of Gas network leakages CO2 emissions, ranging from 16% in summer to 4% in winter, and cannot therefore be neglected when assessing greenhouse impact of cities. -

A Diurnal Carbon Engine Explains 13C-Enriched Carbonates

A diurnal carbon engine explains 13C-enriched carbonates without increasing the global production of oxygen Emily C. Geymana,1 and Adam C. Maloofa aDepartment of Geosciences, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544 Edited by Donald E. Canfield, Institute of Biology and Nordic Center for Earth Evolution, University of Southern Denmark, Odense M., Denmark, and approved October 8, 2019 (received for review May 21, 2019) In the past 3 billion years, significant volumes of carbonate processes can be constrained by visualizing the carbon evolution with high carbon-isotopic (δ13C) values accumulated on shallow of banktop seawater in a Deffeyes diagram (9) (Fig. 2B), since continental shelves. These deposits frequently are interpreted each mechanism induces a characteristic change in DIC and total as records of elevated global organic carbon burial. However, alkalinity (TA) (Table 1). Observations of TOC (5) and DIC vs. through the stoichiometry of primary production, organic carbon TA (7) from the GBB constrain the relative sizes of the net car- burial releases a proportional amount of O2, predicting unrealis- bonate, gas-exchange, and organic fluxes to be 62, 37, and <1%, tic rises in atmospheric pO2 during the 1 to 100 million year-long respectively (Fig. 2). Although the net burial of organic matter positive δ13C excursions that punctuate the geological record. is close to zero, the flux of carbon between organic matter and This carbon–oxygen paradox assumes that the δ13C of shallow the DIC pool over the course of a single diurnal (24-h) cycle water carbonates reflects the δ13C of global seawater-dissolved can exceed the gross atmospheric and carbonate fluxes by over inorganic carbon (DIC). -

Guide to Best Practices for Ocean CO2 Measurements

Guide to Best Practices for Ocean C0 for to Best Practices Guide 2 probe Measurments to digital thermometer thermometer probe to e.m.f. measuring HCl/NaCl system titrant burette out to thermostat bath combination electrode In from thermostat bath mL Metrohm Dosimat STIR Guide to Best Practices for 2007 This Guide contains the most up-to-date information available on the Ocean CO2 Measurements chemistry of CO2 in sea water and the methodology of determining carbon system parameters, and is an attempt to serve as a clear and PICES SPECIAL PUBLICATION 3 unambiguous set of instructions to investigators who are setting up to SPECIAL PUBLICATION PICES IOCCP REPORT No. 8 analyze these parameters in sea water. North Pacific Marine Science Organization 3 PICES SP3_Cover.indd 1 12/13/07 4:16:07 PM Publisher Citation Instructions North Pacific Marine Science Organization Dickson, A.G., Sabine, C.L. and Christian, J.R. (Eds.) 2007. P.O. Box 6000 Guide to Best Practices for Ocean CO2 Measurements. Sidney, BC V8L 4B2 PICES Special Publication 3, 191 pp. Canada www.pices.int Graphic Design Cover and Tabs Caveat alkemi creative This report was developed under the guidance of the Victoria, BC, Canada PICES Science Board and its Section on Carbon and climate. The views expressed in this report are those of participating scientists under their responsibilities. ISSN: 1813-8519 ISBN: 1-897176-07-4 This book is printed on FSC certified paper. The cover contains 10% post-consumer recycled content. PICES SP3_Cover.indd 2 12/13/07 4:16:11 PM Guide to Best Practices for Ocean CO2 Measurements PICES SPECIAL PUBLICATION 3 IOCCP REPORT No. -

Understanding the Ocean's Biological Carbon Pump in the Past: Do We Have the Right Tools?

Manuscript prepared for Earth-Science Reviews Date: 3 March 2017 Understanding the ocean’s biological carbon pump in the past: Do we have the right tools? Dominik Hülse1, Sandra Arndt1, Jamie D. Wilson1, Guy Munhoven2, and Andy Ridgwell1, 3 1School of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol, Clifton, Bristol BS8 1SS, UK 2Institute of Astrophysics and Geophysics, University of Liège, B-4000 Liège, Belgium 3Department of Earth Sciences, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521, USA Correspondence to: D. Hülse ([email protected]) Keywords: Biological carbon pump; Earth system models; Ocean biogeochemistry; Marine sedi- ments; Paleoceanography Abstract. The ocean is the biggest carbon reservoir in the surficial carbon cycle and, thus, plays a crucial role in regulating atmospheric CO2 concentrations. Arguably, the most important single com- 5 ponent of the oceanic carbon cycle is the biologically driven sequestration of carbon in both organic and inorganic form- the so-called biological carbon pump. Over the geological past, the intensity of the biological carbon pump has experienced important variability linked to extreme climate events and perturbations of the global carbon cycle. Over the past decades, significant progress has been made in understanding the complex process interplay that controls the intensity of the biological 10 carbon pump. In addition, a number of different paleoclimate modelling tools have been developed and applied to quantitatively explore the biological carbon pump during past climate perturbations and its possible feedbacks on the evolution of the global climate over geological timescales. Here we provide the first, comprehensive overview of the description of the biological carbon pumpin these paleoclimate models with the aim of critically evaluating their ability to represent past marine 15 carbon cycle dynamics. -

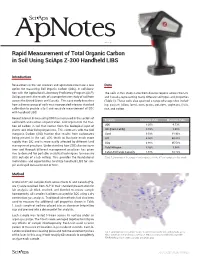

Rapid Measurement of Total Organic Carbon in Soil Using Sciaps Z-300 Handheld LIBS

rev 12/18 Rapid Measurement of Total Organic Carbon in Soil Using SciAps Z-300 Handheld LIBS Introduction Researchers in the soil sciences and agriculture now have a new Data option for measuring Soil Organic Carbon (SOC). In collabora- tion with the Agricultural Laboratory Proficiency Program (ALP), The soils in this study came from diverse regions across the U.S. SciAps presents the results of a comprehensive study of soil from and Canada, representing many different soil types and properties across the United States and Canada. This case study describes (Table 1). These soils also spanned a range of usage sites includ- how a diverse group of soils was incorporated into one standard ing: pasture, fallow, forest, corn, grains, potatoes, soybeans, fruits, calibration to provide a fast and accurate measurement of SOC rice, and cotton. with handheld LIBS. Recent interest in measuring SOC has increased in the sectors of Property Minimum Value Maximum Value soil health and carbon sequestration. SOC represents the frac- SOC 0.25% 6.73% tion of carbon in soil that comes from the biological input of plants and other living organisms. This contrasts with the Soil SIC (From CaCO3) 0.01% 1.49% Inorganic Carbon (SIC) fraction that results from carbonates Sand 9.58% 91.93% being present in the soil. SOC tends to fluctuate much more Silt 4.00% 66.00% rapidly than SIC and is more easily affected by different land Clay 3.90% 45.50% management practices. Understanding how SOC changes over Total Nitrogen 0.02% 1.98% time and through different management practices has given Cation-Exchange Capacity 1.87% 32.72% rise to demand for portable analytical techniques to measure SOC outside of a lab setting. -

Estimation of Atmospheric Total Organic Carbon (TOC) – Paving the Path Towards Carbon Budget Closure

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 459–471, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-459-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Estimation of atmospheric total organic carbon (TOC) – paving the path towards carbon budget closure Mingxi Yang1 and Zoë L. Fleming2,a 1Plymouth Marine Laboratory, Plymouth, UK 2National Centre for Atmospheric Science (NCAS), Department of Chemistry, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK anow at: Center for Climate and Resilience Research (CR2), Departamento de Geofísica, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile Correspondence: Mingxi Yang ([email protected]) Received: 8 October 2018 – Discussion started: 12 October 2018 Revised: 15 December 2018 – Accepted: 18 December 2018 – Published: 14 January 2019 Abstract. The atmosphere contains a rich variety of reactive butions from a number of known organic compounds present organic compounds, including gaseous volatile organic car- in marine air that were not detected by the PTR-MS are as- bon (VOCs), carbonaceous aerosols, and other organic com- sessed within the context of the TOC budget. Finally, we note pounds at varying volatility. Here we present a novel and that the use of a short, heated sample tube can improve the simple approach to measure atmospheric non-methane total transmission of organics to the analyzer, while operating our organic carbon (TOC) based on catalytic oxidation of organ- system alternately with and without a particle filter should ics in bulk air to carbon dioxide. This method shows little enable a better separation of semi-volatile and particulate or- sensitivity towards humidity and near 100 % oxidation effi- ganics from the VOCs within the TOC budget.