The Private Finance Initiative in English Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exhibition Academy

EXHIBITION Ac ade my MDCCCCX Forty - second The Exhibition o ens the firs t M onda in Ma and cl ose h p y y, s t e first Monda in Au us t y g . Hour s o A mi ss i on from 8 A M ill P M xce t on the fir . t . e s f d 7 . ( p t da wh en the doors do not o n f r I O Ho y, pe be o e ur ofclo in 0 P M s g, 7 . 3 . ’ P r i ce o A omiss i oi z I s f , . P i c o Cata lo ue L ar i mall r e : e w th a er cover I s . S wi h f g g , p p , , t a er cover 1s . Small bound i n cloth with encil 1s 6d p p , , , p , . S as on Ti cket s e , 5 . isitors are n ot re uired to ive u their S ti cks Umbr ellas or V q g p , P ar as ols b efore enteri ng the Gall eri es but they c an leave them if the wish with th e attendant s at th e loak oom y , C R in the E tranc ll The oth r att ndants are stric l n e Ha . e e t y forbidden take h r ofan thin to c a ge y g . Tli e Refr eslzmefz t Room i s r eached by a s taircase leading out ofthe Water Colour oom R . -

Annex E2 Visit Reports.Pdf

Annex E2 Final Report Working Group 1 – Engineers WG1: Report on visit to the Ledbury Estate, Peckham, Southwark November 30th 2018. The Ledbury Estate is in Peckham and includes four 14-storey Large Panel System (LPS) tower blocks. The estate belongs to Southwark Council. The buildings were built for the GLC between 1968 and 1970. The dates of construction as listed as Bromyard (1968), Sarnsfield (1969), Skenfrith (1969) and Peterchurch House (1970). The WG1 group visited Peterchurch House on November 30th 2018. The WG1 group was met by Tony Hunter, Head of Engineering, and, Stuart Davis, Director of Asset Management and Mike Tyrrell, Director of the Ledbury Estate. The Ledbury website https://www.southwark.gov.uk/housing/safety-in-the-home/fire-safety-on-the- ledbury-estate?chapter=2 includes the latest Fire Risk Assessments, the Arup Structural Reports and various Residents Voice documents. This allowed us a good understanding of the site situation before the visit. In addition, Tony Hunter sent us copies of various standard regulatory reports. Southwark use Rowanwood Apex Asset Management System to manage their regulatory and ppm work. Following the Structural Surveys carried out by Arup in November 2017 which advised that the tower construction was not adequate to withstand a gas explosion, all piped gas was removed from the Ledbury Estate and a distributed heat system installed with Heat Interface Units (HIU) in each flat. Currently fed by an external boiler system. A tour of Peterchurch House was made including a visit to an empty flat where the Arup investigation points could be seen. -

NGA4 Harold Isherwood Kay Papers 1914-1946

NGA4 Harold Isherwood Kay Papers 1914-1946 GB 345 National Gallery Archive NGA4 NGA4 Harold Isherwood Kay Papers 1914-1946 5 boxes Harold Isherwood Kay Administrative history Harold Isherwood Kay was born on 19 November 1893, the son of Alfred Kay and Margaret Isherwood. He married Barbara Cox, daughter of Oswald Cox in 1927, there were no children. Kay fought in the First World War 1914-1919 and was a prisoner of war in Germany in 1918. He was employed by the National Gallery from 1919 until his death in 1938, holding the posts of Photographic Assistant from 1919-1921; Assistant from 1921-1934; and Keeper and Secretary from 1934-1938. Kay spent much of his time travelling around Britain and Europe looking at works of art held by museums, galleries, art dealers, and private individuals. Kay contributed to a variety of art magazines including The Burlington Magazine and The Connoisseur. Two of his most noted articles are 'John Sell Cotman's Letters from Normandy' in the Walpole Society Annual, 1926 and 1927, and 'A Survey of Spanish Painting' (Monograph) in The Burlington Magazine, 1927. From the late 1920s until his death in 1938 Kay was working on a book about the history of Spanish Painting which was to be published by The Medici Society. He completed a draft but the book was never published. HIK was a member of the Union and Burlington Fine Arts Clubs. He died on 10 August 1938 following an appendicitis operation, aged 44. Provenance and immediate source of acquisition The Harold Isherwood Kay papers were acquired by the National Gallery in 1991. -

HMM Cover 19/02/2019 16:26 Page 1

HMM0203_2019 Cover_HMM Cover 19/02/2019 16:26 Page 1 Commission demands 3.1 million new HOUSING homes Another UC MANAGEMENT u-turn Grenfell Inquiry on pause & MAINTENANCE £1 billion TA bill Homeless deaths FEB/MAR 2019 – shocking rise Pro-active roof asset management Dean Wincott of Langley Waterproong Systems explains the benets of implementing a full roof asset management plan. See page 43 HMM0203_2019 Cover_HMM Cover 19/02/2019 16:26 Page 2 A w w w w w 51 HMM02_2019 03-18_Layout 1 25/02/2019 13:28 Page 3 Feb/ Mar Contents19 31 In this issue of Features HOUSING MANAGEMENT 31 Insulation & Energy Efficiency & MAINTENANCE Roofs renewed Industry news...........................................04 Kingspan Insulation’s Adrian Pargeter explains why tapered insulation systems Events ..........................................................06 should be considered when refurbishing flat roofs in order to avoid water ponding Appointments & News ..........................27 Futurebuild Show Preview...................29 Bathroom Refurbishment 35 Directory.....................................................51 Comfort height – a big deal Lecico’s Adam Lay discusses what comfort height means and why it’s something to consider when pla nning a bathroom refurbishment 39 Doors, Windows & Glazing The no compromise composite door 29 John Whalley of Nationwide Windows & Doors discusses the advantages of composite doors for social housing Products 43 Roofing Efficiency Pro-active roof asset management Air Quality & Ventilation (HVAC Control) .........................................30 -

Elsworthy Road Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Strategy

Elsworthy Road Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Strategy Adopted 14 July 2009 CONTENTS PART 1: CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL 1.0 INTRODUCTION Purpose of the Appraisal Designation 2.0 STATUTORY AND PLANNING POLICY CONTEXT 3.0 SPECIAL INTEREST OF THE CONSERVATION AREA Context and Evolution Spatial Character and Views Building Typology and Form Prevalent and Traditional Building Materials Characteristic Details Landscape and Public Realm 4.0 LOCATION AND SETTING Location and Context Topography General Character and Plan Form Prevailing and Former Uses 5.0 HISTORIC DEVELOPMENT Pre 1750 1750-1800 1800-1850 1850-1900 1900 onwards 6.0 CHARACTER ANALYSIS Land use, activity and the influence of former uses Building Character and Qualities Townscape Character 7.0 HERITAGE AUDIT Introduction PART 2: MANAGEMENT STRATEGY 8.0 INTRODUCTION Background Policy and Legislation 9.0 MONITORING AND REVIEW Monitoring Review 10.0 MAINTAINING CHARACTER General Approach 11.0 BOUNDARY CHANGES Additions and deletions considered 12.0 CURRENT ISSUES 13.0 MANAGEMENT OF CHANGE Investment and Maintenance Listed Buildings Unlisted Buildings Control over New Development Basements Demolition Control of Advertisements Development Briefs and Design Guidance Public Realm Strategy Enforcement Article 4 Directions 14.0 OTHER ISSUES Promoting Design Quality Potential Enhancement Schemes/Programmes Resources BIBLIOGRAPHY LIST OF MAPS APPENDICES: PART 2 Appendix 1: Conservation Area Boundary Appendix 2: Designation Area Boundaries & Dates Appendix 3: Urban Grain Appendix 4: Topography Appendix 5: Historic Plans i) OS Map 1871 ii) OS Map 1894 iii) OS Map 1914 iv) OS Map 1935 Appendix 6: Sub-Areas within the Conservation Area Appendix 7: Built Heritage Audit Appendix 8: Built Heritage Audit Plan PART 1: CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Elsworthy Conservation Area covers an approximately 16.4 hectare area extending from Primrose Hill Road in the east to Avenue Road in the west, marking the boundary between the London Borough of Camden and the City of Westminster. -

A New Deal for Social Housing

Evidence from Pembroke Park Residents Association Below are a few brief paragraphs provided for this consultation by Suzy Killip, Chair of Pembroke Park Residents Association, on the lack of both proper housing regulations and where regulations do exist, how they are flouted. BACKGROUND: Pembroke Park is a mixed tenure estate of approximately 400 units in Ruislip, North London. ALL tenures have experienced a lack of proper implementation of legal regulations from the builder, Taylor Wimpey and the HA/Management Company, A2 Dominion. This includes poor insulation in the flats and houses, fire regulations in the blocks of flats not adhered to, disrepairs leading to safety issues and a general disregard for the enforcement of legal regulations across the Estate. INSULATION Because Taylor Wimpey are self inspecting and A2 Dominion were appointed by them as the HA and Management Company there is already a conflict of interest. The insulation of all properties across the tenures is substandard and the social housing properties are affected the worst. The buildings were not inspected properly either by TW or by A2D when they took the properties over. Only one of the properties has been rectified after much pressure by us, the PPRA, the Council, Hillingdon, our Councillors and Nick Hurd MP. This was after the very disabled child in the house nearly died 3 times from sleeping in a bedroom that went down to 13 degrees C in the winter and up to 28 degrees C in the summer during heat waves. Heating these properties in the winter from the DH System means that our residents are heating the street and that the cost is exorbitant. -

PHASE 2, MODULE 1: OPENING SUBMISSIONS on BEHALF of the Bsrs

GRENFELL TOWER INQUIRY ______________________________________________________________________ PHASE 2, MODULE 1: OPENING SUBMISSIONS ON BEHALF OF THE BSRs REPRESENTED BY TEAM 2 ______________________________________________________________________ Introduction 1. The Team 2 BSRs are grateful to the Chairman and his team for the Phase 1 report. It is clear that a huge amount of hard work has gone into the report. 2. However, much remains to be done in Phase 2. The work is urgent: two and a half years have now passed since the tragic events of June 2017. Many residents of tower blocks up and down the country, including bereaved family members, are concerned about the cladding and materials used in their own buildings and struggling to get information from their landlords. These concerns are increased when it is discovered, for example, that Rydon are still working on large public housing projects and were, until very recently, still being allowed to bid for, or work on, high-rise buildings.1 There have also been a number of well-publicised fires where the cladding has been a substantial contributing factor.2 3. Our clients seek two main things from Phase 2 of the Inquiry: the truth; and justice, in the form of accountability and change. 4. So far as accountability is concerned, the Inquiry will need to demolish the wall of obfuscation set up by the corporate CPs and hold to account the many individuals, firms, companies and organisations who have contributed to this tragedy. The Inquiry will, no doubt, be assisted in this task by the extremely robust, indeed devastating, expert reports. For example, in relation to Exova, Barbara Lane refers to very serious evidence of professional negligence.3 This is extremely strong, but fully justified, language from a very experienced expert. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Monday Volume 688 1 February 2021 No. 169 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 1 February 2021 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 663 1 FEBRUARY 2021 664 across the country, so will the Secretary of State update House of Commons this House as to how his Department aims to ensure that the British taxpayer is not left paying huge rents on Monday 1 February 2021 a great number of empty properties, as has already happened, when these sites are closed? How many of these defence estate sites will be affected by the Crichel The House met at half-past Two o’clock Down rule? PRAYERS Mr Wallace: The hon. Gentleman makes an important point. The defence estate optimisation programme was [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] and is planned to unlock £1.4 billion, to be reinvested Virtual participation in proceedings commenced (Orders, in an overall plan of a £5.1 billion investment in the 4 June and 30 December 2020). defence estate across the board, helping soldiers, sailors and air force personnel with better quality accommodation [NB: [V] denotes a Member participating virtually.] and a better training estate. He is right to point out the challenges relating to historical problems with both private finance initiatives and the Annington home deal Oral Answers to Questions at the end of 1997. Some of the PFI schemes introduced under his Government lay a heavy burden on the defence budget. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Environment and Communities

Environment and Communities Scrutiny Committee Wednesday 7 March 2018 at 10.00 am Cabinet Suite - Shire Hall, Gloucester AGENDA 1 APOLOGIES Laura Powick To note any apologies for absence. 2 MINUTES (Pages 1 - 8) Laura Powick To confirm and sign the minutes of the meeting held on 17 January 2018. 3 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST Laura Powick Members of the Committee are invited to declare any pecuniary or personal interests relating to specific matters on the agenda. Please see note (a) at the end of the agenda. 4 MOTION 787: PAVEMENTS (Pages 9 - 12) Cllr Vernon Smith To receive a report on measures to improve the inspection and fixing of pavements. 5 A417 'MISSING LINK' CONSULTATION (Pages 13 - 22) Amanda Lawson-Smith To consider a report on the A417 ‘Missing Link’ consultation. 6 A429 TASK GROUP (Pages 23 - 36) Cllr Nigel Moor To receive an update report on the A429 Task Group Date Published:27 February 2018 recommendations. 7 CHIEF FIRE OFFICER REPORT (Pages 37 - 204) Stewart Edgar The Committee to note a report from the Chief Fire Officer, detailing information on the portfolio of services provided by the Gloucestershire Fire and Rescue Service on behalf of Gloucestershire County Council. 8 COMMISSIONING DIRECTORS REPORT (Pages 205 - 228) Nigel Riglar Nigel Riglar, Commissioning Director: Communities and Infrastructure to update the Committee on current issues. 9 WORK PLAN (Pages 229 - 230) Cllr Robert Bird To review the committee work plan and suggest items for consideration at future meetings. (Work plan attached). 10 FUTURE MEETINGS Laura -

Fuel Poverty Action Annual Report AGM 13 September 2018

Fuel Poverty Action Annual Report AGM 13 September 2018 Year overview This has been a very exciting year for FPA. We’ve been active on all fronts, and in many different ways. We have widened and deepened our connections with other active and effective organisations, have made contact with some that we had not known before, and have helped to establish some new networks. It’s been a year in two halves. The period up to January 2018 was more focused on poverty and energy prices, with a lot of effort put into research, clarifying demands around bringing bills down, organising an open letter to Ofgem, and submitting reports and consultation responses to the GLA and others. Since January, with the launch of our campaign for Safe Cladding and Insulation Now, we have been intensively involved in the fight for warm, safe, non-combustible, well insulated housing. We have been working with tenants and residents associations and many others in the housing movement, and have expanded our connections with MPs, trade unionists, and grassroots organisations. Core work has continued throughout. We work with individuals in fuel poverty wanting advice and support in dealing with suppliers and landlords, and with organisations of people in fuel poverty or at risk of it, particularly pensioners and people with disabilities. We have increased our media presence, with over 30 media appearances in the course of the year, and helped people struggling with energy bills get a chance to speak out in the press, on the radio and on TV. We also re-launched the second edition of our popular Mini-guide on energy rights. -

Introduction: Grenfell and the Return of 'Social Murder'

Introduction: Grenfell and the return of ‘social murder’ At around 12.54 a.m. on 14 June 2017, an exploding fridge freezer set fire to a flat on the fourth floor of Grenfell Tower, a 24-storey public housing block of flats in the west London borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Ten minutes later, firefighters were on the scene, handling what appeared to be a routine job – post-war high-rises like Grenfell had been designed to contain fires within separate flats and the residents had been told to ‘stay put’ rather than evacuate. But the fire did not behave as expected. Within 15 minutes, a column of flames had rapidly climbed up the outside of the tower block to the uppermost storey, and shortly after the whole building was ablaze. Survivors and emergency service workers would later recount the sheer horror of human carnage that took place, which they were helpless to prevent. As people leapt from the tower, others trapped inside climbed to the upper floors and roof, some trying to make ropes from sheets, others making phone calls and video messages to their loved ones, begging for help or saying goodbye. Those who survived did so in large part by ignoring the official fire safety advice to ‘stay put’ in their flats. It would take 250 firefighters, 70 fire engines and 60 hours to extinguish the fire that eventually claimed the lives of 72 people in one of Britain’s most deadly infernos since the Great Fire of London of 1666.1 While the architectural and construction quality of tower blocks has attracted long-standing critique, Grenfell Tower was a beacon of the high building standards brought in after the 1968 Ronan Point disaster in east London that killed four people when a new tower block partially collapsed following a gas explosion. -

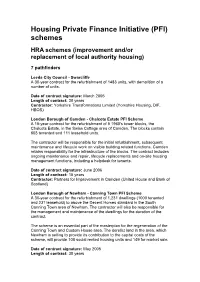

PFI) Schemes HRA Schemes (Improvement And/Or Replacement of Local Authority Housing)

Housing Private Finance Initiative (PFI) schemes HRA schemes (improvement and/or replacement of local authority housing) 7 pathfinders Leeds City Council - Swarcliffe A 30-year contract for the refurbishment of 1483 units, with demolition of a number of units. Date of contract signature: March 2005 Length of contract: 30 years Contractor: Yorkshire Transformations Limited (Yorkshire Housing, DIF, HBOS) London Borough of Camden - Chalcots Estate PFI Scheme A 15-year contract for the refurbishment of 5 1960's tower blocks, the Chalcots Estate, in the Swiss Cottage area of Camden. The blocks contain 603 tenanted and 111 leasehold units. The contractor will be responsible for the initial refurbishment, subsequent maintenance and lifecycle work on visible building related functions. Camden retains responsibility for the infrastructure of the blocks. The contract includes ongoing maintenance and repair, lifecycle replacements and on-site housing management functions, including a helpdesk for tenants. Date of contract signature: June 2006 Length of contract: 15 years Contractor: Partners for Improvement in Camden (United House and Bank of Scotland) London Borough of Newham - Canning Town PFI Scheme A 30-year contract for the refurbishment of 1,231 dwellings (1000 tenanted and 231 leasehold) to above the Decent Homes standard in the South Canning Town area of Newham. The contractor will also be responsible for the management and maintenance of the dwellings for the duration of the contract. The scheme is an essential part of the masterplan for the regeneration of the Canning Town and Custom House area. The derelict land in the area, which Newham is selling to provide its contribution to the capital costs of the scheme, will provide 108 social rented housing units and 149 for market sale.