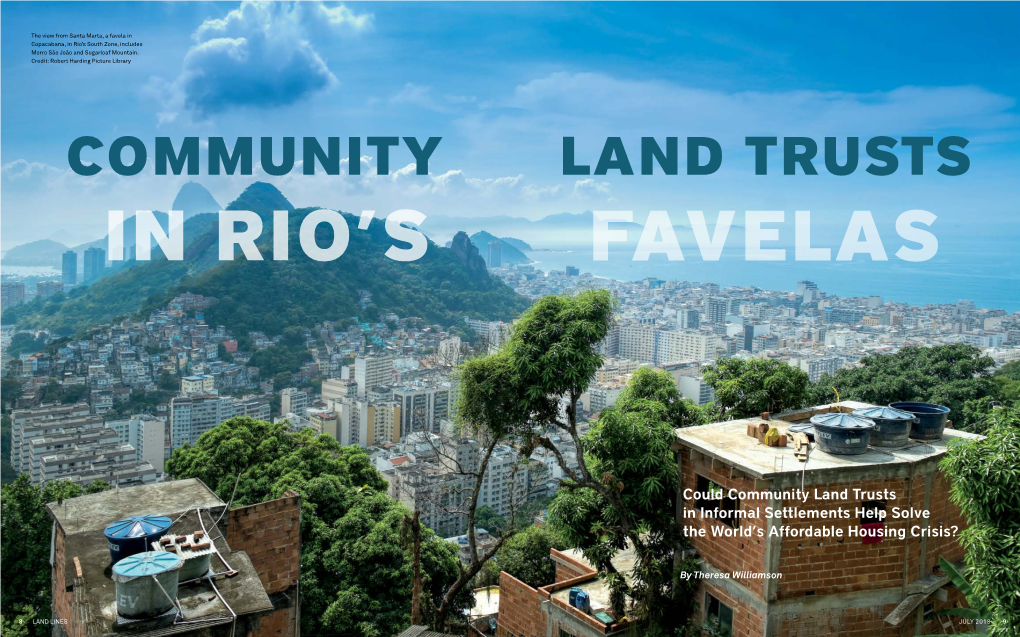

Community Land Trusts in Rio's Favelas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sscott Megacities S Paulo Rio Edv2

Megacities: A Study of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro Grade Level: 9-12 Subject: Geography, World History Key Words: megacities, urban design Time Frame: 1-2 days Designed by: Sharlyn Scott School District: Desert Vista High School Summary: Using São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro as case studies to research and compare/contrast, students will gain a greater understanding of basic urban geography and the history and geography of Brazil. Background Information: Megacities are urban conglomerations with populations exceeding 10 million; sources vary on exactly how many global cities (and their urban sprawl) can be categorized as such. According to the United Nations, there were an estimated 37 cities with more than 10 million people in 2015, compared to just 14 in 1995, and they estimate there will be 41 (maybe as many as 43) megacities by 2030. Two of the three megacities in Latin America are in Brazil: São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. For more information about megacities, São Paulo, and Rio de Janeiro, see: • Blakemore (2016) “Five Things to Know About Megacities” (Smithsonian): https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/five-things-to-know-about- megacities-180958937/ • Catalytic Communities “Favela Facts”: http://catcomm.org/favela-facts/ • "São Paulo: South America’s Megacity”: https://www.youtube.com/watch? v=sNEeY_gXFBc Student Objectives Students will be able to • Consider the needs of human populations within a city (their own as an introduction) and what challenges/successes city planners and leaders, as well as the population of that city, experience. • Research characteristics of the physical geography and human geography of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro in order to create together a clearer picture and understanding of these two megacities in Brazil, and the successes/challenges both have experienced. -

Favelas in the Media Report

Favelas in the Media: How the Global Narrative on Favelas Changed During Rio’s Mega-Event Years 1094 articles - eight global outlets - 2008-2016 Research conducted by Catalytic Communities in Rio de Janeiro December 2016 Lead Researcher: Cerianne Robertson, Catalytic Communities Research Coordinator Contents Research Contributors: Lara Mancinelli Alex Besser Nashwa Al-sharki Sophia Zaia Gabi Weldon Chris Peel Megan Griffin Raven Hayes Amy Rodenberger Natalie Southwick Claudia Sandell Juliana Ritter Aldair Arriola-Gomez Mikayla Ribeiro INTRODUCTION 5 Nicole Pena Ian Waldron Sam Salvesen Emilia Sens EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 9 Benito Aranda-Comer Wendy Muse Sinek Marcela Benavides (CatComm Board of Directors) METHODOLOGY 13 Gabriela Brand Theresa Williamson Clare Huggins (CatComm Executive Director) FINDINGS 19 Jody van Mastrigt Roseli Franco Ciara Long (CatComm Program Director) 01. Centrality ................................................................................................ 20 Rhona Mackay 02. Favela Specificity .................................................................................... 22 Translation: 03. Perspective ............................................................................................. 29 04. Language ................................................................................................ 33 Geovanna Giannini Leonardo Braga Nobre 05. Topics ..................................................................................................... 39 Kris Bruscatto Arianne Reis 06. Portrayal ................................................................................................ -

Slumssymposium Emergingthemes

SYMPOSIUM REFLECTIONS EMERGING THEMES, FUTURE RESEARCH AND NEXT STEPS Janice Perlman1 Mega-Cities Project [email protected] Outline I. Introduction II. Symposium Overview III. Areas of Convergence IV. Areas of Divergence V. Emerging Themes VI. Future Research VII. Next Conference VIII. List of Participants 1 Thanks to Guilherme Formicki for his assistance in the preparation of this report. The full symposium can be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2IJFUnVKxFQ&list=PLpMsNp6Vpvu3D0uXyFvDSrMsZm7Yul wRn. The agenda is available here: https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Harvard_Slums_Symposium_Schedule_rvsd_091 718_0.pdf 2 I. Introduction This reflection is based on a three-day symposium sponsored by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, the Joint Center for Housing Studies, and the Harvard Graduate School of Design from Sept. 20-22, 2018.2 This report is not intended to be a summary of the panels and discussions, but rather to highlight areas of convergence and divergence among participants, and to draw out themes that arose in our discussions. In addition, the report develops an agenda for future research and a follow-up conference. The gathering proceeded from the recognition that slums are an enduring feature of the urban landscape. As stated in the Concept Note, the persistence of slums can be traced to “failures to effectively address poverty and inequality, distorted land markets, and systemic social exclusion. These failures are, in turn, rooted in the very way policymakers, global media, and intellectuals conceptualize and represent how, why and by whom slums are produced, maintained and reproduced.” In recognition of this fact, the goals of the symposium were, “To advance new ideas, policies and tools that improve existing slums and generate alternatives to future ones.” To that end, symposium organizers posed the following questions: 1. -

RESPONDING to COMPLEXITY a Case Study on the Use of “Developmental Evaluation for Managing Adaptively”

RESPONDING TO COMPLEXITY A Case Study on the Use of “Developmental Evaluation for Managing Adaptively” A Master’s Capstone in partial fulfillment of the Master of Education in International Education at the University of Massachusetts Amherst Spring 2017 Kayla Boisvert Candidate to Master of Education in International Education University of Massachusetts Amherst Amherst, Massachusetts May 10, 2017 Abstract Over the past 15 years, the international development field has increasingly emphasized the need to improve aid effectiveness. While there have been many gains as a result of this emphasis, many critique the mechanisms that have emerged to enhance aid effectiveness, particularly claiming that they inappropriately force adherence to predefined plans and hold programs accountable for activities and outputs, not outcomes. However, with growing acceptance of the complexity of development challenges, different ways to design, manage, and evaluate projects are beginning to take hold that better reflect this reality. Many development practitioners explain that Developmental Evaluation (DE) and Adaptive Management (AM) offer alternatives to traditional management and monitoring and evaluation approaches that are better suited to address complex challenges. Both DE and AM are approaches for rapidly and systematically collecting data for the purpose of adapting projects in the face of complexity. There are many advocates for the use of DE and AM in complex development contexts, as well as some case studies on how these approaches are being applied. This study aims to build on existing literature that provides examples of how DE and AM are being customized to address complex development challenges by describing and analyzing how one non-governmental organization, Catalytic Communities (CatComm), working in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, uses DE for Managing Adaptively, a term we have used to name their approach to management and evaluation. -

The Favela Housing Rights Movement of Rio De Janeiro

‘Não são tijolos; são histórias’: The Favela Housing Rights Movement of Rio de Janeiro Jennifer Ashley Chisholm Department of Sociology University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy King’s College February 2019 To my family and to those who struggle for justice [ii] Declaration This thesis is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my thesis has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the relevant Degree Committee. Jennifer Chisholm February 2019 [iii] Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my parents who have been a constant source of support and understanding. I also thank Jeff as well as all my advisors and teachers that have helped me along the way. I am grateful to the people who lent me their stories and appreciate the kindness of friends, acquaintances, and strangers who helped me through the challenges of fieldwork. -

Summary of an Experiment in Global Engagement

CATALYSTS FOR CHANGE Paths out of Poverty Summary of an Experiment in Global Engagement INSTITUTE FOR THE FUTURE 124 University Avenue, 2nd Floor, Palo Alto, CA 94301 | 650.854.6322 www.iftf.org ABOUT ... INSTITUTE FOR THE FUTURE The Institute for the Future is an independent, nonprofit strategic research group celebrating more than 40 years of forecasting experience. The core of our work is identifying emerging trends and discontinuities that will transform global society and the global marketplace. We provide our members with insights into business strategy, design process, innovation, and social dilemmas. Our research spans a broad territory of deeply transformative trends, from health and health care to technology, the workplace, and human identity. The Institute for the Future is located in Palo Alto, California. THE ROCKEFELLER FOUNDATION The Rockefeller Foundation supports work that expands opportunity and strengthens resilience to social, economic, health and environmental challenges—affirming its pioneering philanthropic mission since 1913 to promote the well-being of humanity. The Foundation operates both within the United States and around the world. The Foundation's efforts are overseen by an independent Board of Trustees and managed by its president through a leadership team drawn from scholarly, scientific, and professional disciplines. © 2012 Institute for the Future. All rights reserved. Reproduction prohibited without written permission. SR-1535 Contents 1 | Introduction 1 2 | Game Objectives and Game Design 3 3 | Pre-Game -

Ecosystem Services for Poverty Alleviation in Amazonia

Ecosystem Services for Poverty Alleviation in Amazonia A report of a capacity-building project to design a research agenda on the links between the natural capital of Amazonian forests and water, food, health, livelihood, climate and energy securities. – Global Canopy Programme – Grupo de Trabalho Amazônico – Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais – London School of Economics – Met Office Hadley Centre – Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro – Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina – Universidad Nacional de Colombia – University of Edinburgh – University of Oxford – University of1 Vermont This Report presents the activities and results of an ESPA capacity-building project (grant NE/G008531/1) entitled: Valuing rainforests as global eco-utilities: a novel mechanism to pay communities for ecosystem services provided by the Amazon. The project was led by the University of Edinburgh and the Global Canopy Programme in the UK; Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (INPE) in Brazil; Universidad Nacional de Colombia (UNAL) and Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina (UNALM) in Peru in collaboration with a number of academic and NGO partners. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the organisations involved in this project, or those of its funders. Acknowledgements The project leaders would like to warmly thank all those who gave up their valuable time to engage in this capacity-building project. In particular, the members of the project team who committed their energies at workshops and meetings and through the writing of reports and project proposals. We especially thank the stakeholders in local communities and government who provided their insights into the process. -

Vila Autódromo in Rio De Janeiro: an Unending Struggle for Recognition

The Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric, is the international gateway for the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB). Eight departments, associated research institutions and the Norwegian College of Veterinary Medicine in Oslo. Established in 1986, Noragric’s contribution to international development lies in the interface between research, education (Bachelor, Master and PhD programmes) and assignments. The Noragric Master theses are the final theses submitted by students in order to fulfill the requirements under the Noragric Master programme “International Environmental Studies”, “Development Studies” and other Master programmes. The findings in this thesis do not necessarily reflect the views of Noragric. Extracts from this publication may only be reproduced after prior consultation with the author and on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation contact Noragric. ©Aimê Lima Olaussen, September 2012 [email protected] Noragric Department of International Environment and Development Studies P.O. Box 5003 N-1432 Ås Norway Tel.: +47 64 96 52 00 Fax: +47 64 96 52 01 Internet: http://www.umb.no/noragric ii Declaration I, Aimê Lima Olaussen, declare that this thesis is a result of my research investigations and findings. Sources of information other than my own have been acknowledged and a reference list has been appended. This work has not been previously submitted to any other university for award of any type of academic degree. Ås, September 15th 2011 ……………………………….. iii iv Acknowledgement There are several people who have contributed to make this thesis possible, both in Norway and in Brazil. My deepest gratitude goes, first and foremost, to the people in Vila Autódromo, especially to Mr. -

Social Sustainability: the Role of Ecotourism in Regenerating Cultural and Environmental Histories in Rio De Janeiro Nia Mcallister Pomona College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Senior Theses Pomona Student Scholarship 2017 Social Sustainability: The Role of Ecotourism in Regenerating Cultural and Environmental Histories in Rio de Janeiro Nia McAllister Pomona College Recommended Citation McAllister, Nia, "Social Sustainability: The Role of Ecotourism in Regenerating Cultural and Environmental Histories in Rio de Janeiro" (2017). Pomona Senior Theses. 173. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses/173 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pomona Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pomona Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Social Sustainability: The Role of Ecotourism in Regenerating Cultural and Environmental Histories in Rio de Janeiro Nia McAllister In Partial Fulfillment of a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Environmental Analysis 2016-2017 academic year, Pomona College, Claremont, California Readers: Professor Francisco Dóñez Professor Zayn Kassam Acknowledgments First I would like to thank my thesis readers Professor Zayn Kassam and Professor Francisco Dóñez for their continual encouragement, guiding wisdom, and critical feedback throughout the thesis writing process. I would also like to thank Professor Char Miller, my unofficial reader who always provided detailed feedback and constant enthusiasm throughout the entire thesis journey. I am extremely grateful to Pomona College for awarding me the Oldenborg International Research and Travel Grant which provided me the funding and opportunity to return to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil to conduct the interviews for my thesis research. In addition, I would like to thank Nayana Corrêa Bonamichi for assisting with transcribing my research interviews and the Academic Dean’s Office at Pomona College for providing funds to underwrite the transcription. -

Preventing a Favela Whitewashing: How a Tax Code Revision Can Mitigate the Danger of Bare Title Rights to Rio De Janeiro’S Slum Residents

PREVENTING A FAVELA WHITEWASHING: HOW A TAX CODE REVISION CAN MITIGATE THE DANGER OF BARE TITLE RIGHTS TO RIO DE JANEIRO’S SLUM RESIDENTS KRISTA EVENSEN* For decades, government officials in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil have fought to remove favelas from the public view and displace their residents to new or existing favelas at the periphery of the city. The displacement of Rio de Janeiro’s urban poor poses a human rights dilemma where people who have lived on a plot of land for generations are forced to uproot their lives and start anew in areas where city resources to which they previously had access are no longer available. This Note discredits one posited solu- tion to this pervasive issue: vesting favela residents with real title in the land upon which they are living. Although the idea is that vestment would result in the empowerment of slum residents by increasing their rights and providing a weapon against displacement efforts, this Note argues that a vestment solution fails when it is blindly applied without considering the city’s social, political, and economic histories and current climate of the city. Adopting this theory in Rio de Janeiro would increase gentrification and thus result in the same end result of human displacement. This Note posits that for title vestment to be successful, Rio de Janeiro city officials must accompany vestment with a revamping of its current property taxation code, zoning law, and title registration process. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 774 II. BACKGROUND ......................................................................................... 777 A. Historical Perspectives ................................................................... 777 B. Favelas as “Other” ......................................................................... 779 C. -

The Invisible Cyclists Photo by Allison Mannos

No. 184 ISSN 1559-9736 Summer 2010 The Magazine of Planners Network The Invisible Cyclists Mannos Allison by Photo Also In This Issue: 2010 Just Metropolis Conference Reports from Rio, Mexico City, New York and Youngstown, Ohio www.plannersnetwork.org “In our every deliberation, we must consider the impact of our decisions Summer 2010 Issue Contents: The Seventh on the next seven generations.” -From the Great Law of the The Seventh Generation Progressive Planning Leader Pat Rosenthal and Common Iroquois Confederacy Wealth Inc. of Youngstown, Ohio G e n e r a t i o n by Pierre ClAvel...........................................................................Page 20 Beyond Networking, Left Alternatives by Tom Angotti................................................................................Page 2 Did You Miss the 2010 PN Conference? by NORMA rAnTISI........................................................................Page 24 Feature Articles The Long Struggle for Community-Based Planning in New Beyond Networking, Left Alternatives The Invisible Cyclists of Los Angeles York City by omAri Fuller And edgAr BelTrAn....................................Page 4 by eve BAron......................................................................................Page 30 by Tom Angotti The 2016 Olympics in Rio: A Community Plays Against the Researching the “Just City”: A Study of Urban Revitalization in Real Estate Game Toronto, Canada by TheresA WilliAmson...............................................................Page 9 by Jed KilBourn.....................................................................................Page -

Bp1 / Llv Impacts + Beyond

BP1 / LLV IMPACTS + BEYOND Games Monitor [ Briefing paper on London 2012 Olympic Games ] Games Monitor, December 2015 (fifth edition) – replacing previous background papers and extensively revised Other papers in the series: BP 2 / Finance, profit + infrastructure BP 3 / Apparatus (state + media) http://www.gamesmonitor.org.uk/contact_media_centre Games Monitor was founded in 2005 to raise awareness on issues around the London 2012 development process. We can be contacted at [email protected]. Questions on the background papers specifically should be addressed to Carolyn Smith [email protected]. CONTENTS 1. Loss of habitat and Common Land 7 1.1 Wildlife casualties and habitat destruction 7 1.2 Loss of Common Land, historic landscape and open space 8 Lammas Lands Exchange land (Hackney Marshes) Greenwich Park Wanstead Flats Leyton Marsh Drapers Field 2. Clearance of settlements, firms and local sport 13 2.1 Population displacements 13 Homelessness Gypsies and Travellers Clays Lane estate Students living on the Park Village estate Carpenters Estate, Stratford Manor Garden allotments River Lea bargees 2.2 International context of residential displacement 19 Erasure of Roma settlements, Athens 2004 Forced removal, Beijing 2008 Gentrification and resistance, Vancouver 2010 Clashes and inadequate infrastructure, Sochi 2014 Repression in the favelas, Rio 2016 2.3 Local economy: displacement of small businesses 23 2.4 Sporting losses and targets 25 Grassroots sport Cycling Football (soccer) Swimming Cuts to sports finance Sports participation 3. Contamination fears and impact of construction 27 3.1 Radioactive contamination and hazardous waste 27 3.2 Air pollution associated with construction 28 3.3 Impacts of construction on local residents 29 3.4 Sewage contamination 29 4.