JEWS and GOD-FEARERS in the NEW TESTAMENT PERIOD By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GCSE --- Reviewbackgroundgospel

Review: Background to the Gospel 1 Choosing the best ending, write a sentence each for the following. The Roman allowed the Jews what privilege? Which religious party at the time of Jesus A Romans never sentenced Jews to death accepted these books as their only rule of life? B Jews didn’t have to pay taxes to Rome A Sadducees C Jews were excused from serving in the B Pharisees Roman army C Zealots Which two dates approximate to the times when Pharisee ‘ separated one’ implies that they Solomon's Temple and Herod's Temple were A resisted all pagan influences on Judaism. destroyed? B lived alone as hermits in the hills. A 1200 BC, 70 BC C never mixed with the Sadducees. B 440 BC, 120 AD C 586 BC, 70 AD Most scribes were also A Pharisees. What was the major duty of the priests of the B Sadducees. Temple? C Zealots. A to pray B to collect Temple taxes Between which two groups was there no C to offer sacrifice to God on behalf of the common ground? people A Sadducees and Romans B Publicans and Zealots Which of the following is not used to mean the C Sadducees and Pharisees first five books of the Bible? A Law of Moses Which of the following groups was most B Talmud violently opposed to Roman rule? C Torah A Zealots D Pentateuch B Pharisees C Publicans 2 Write each group with a description that best fits. Zealots Conquerors In each case give a one-sentence reason for your Samaritans Collaborators answer. -

Revolutionaries in the First Century

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 36 Issue 3 Article 9 7-1-1996 Revolutionaries in the First Century Kent P. Jackson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Jackson, Kent P. (1996) "Revolutionaries in the First Century," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 36 : Iss. 3 , Article 9. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol36/iss3/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jackson: Revolutionaries in the First Century masada and life in first centuryjudea Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 1996 1 BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 36, Iss. 3 [1996], Art. 9 revolutionaries in the first century kent P jackson zealotszealousZealots terrorists freedom fighters bandits revolutionaries who were those people whose zeal for religion for power or for freedom motivated them to take on the roman empire the great- est force in the ancient world and believe that they could win because the books ofofflaviusjosephusflavius josephus are the only source for most of our understanding of the participants in the first jewish revolt we are necessarily dependent on josephus for the answers to this question 1 his writings will be our guide as we examine the groups and individuals involved in the jewish rebellion I21 in -

Who Were the Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes & Zealots

Who were the Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes & Zealots The Sadducees were mostly members of the wealthy conservative elite. They had opened their hearts to the secular world of Greek culture and commerce, while insisting that the only worthy form of Judaism was to be found in a rather spiritless, fundamentalist, “pure letter-of-the-law” reading of the Torah. Philosophically, they denied such concepts as resurrection, personal immortality, or other ideas that were only found in the Oral tradition (eventually written down in the Talmud). Politically, they contented themselves with the way things were and resisted change – preferring instead to promote cordial relations with the Romans. Although they often held influential positions in society, they were unpopular with the masses who generally opposed all foreign influences. The Pharisees, the largest group, were mostly middle-class Jews who emphasized the exact keeping of the law as it had been interpreted by sages, elders, and rabbis. Politically, they were ardent anti-Hellenists and anti-Romans. The Pharisees were admired by the majority of Jews, but they were never a very large group since most people had neither the education nor the time to join the party and follow all their stringent rules regarding prayer, fasting, festival observance, tithing, etc. Pharisees were greatly influenced by Persian ideas of Good and Evil, and they adhered to the growing belief in the resurrection of the body with an afterlife of rewards and punishments. Over time, many of the finer impulses of Pharisaism would weaken into an empty religious formalism (as is ever the case), focusing on outward actions rather than the inward experience of the soul. -

Zealots: Jesus and His Day Ones 1. Titus 2:11-14 (Zealots Make The

Zealots: Jesus and His Day Ones 1. Titus 2:11-14 (Zealots make the First Resurrection .Zealots have proven themselves to be ride or die with Elohim) ● that he might redeem us from all iniquity, and purify unto himself a peculiar people=First Resurrection ● Zealous of Good Works=Uncompromising when it comes to the commandments 2. Revelation 3:13-22 ● Lukewarm=non-Zealous ● gold tried in the fire=Putting in work for the set ● White raiment=Your colors, your flag, your rag. Your set’s attire. You need this to make the First Resurrection. And just like a gang you must put in work to get it. ● be zealous therefore=Circumspect 3. Psalms 119:138-140 ● Righteousness=Keeping the commandments ● Verse 139=Those around you who transgress the law should cause a zeal in you for Yah’s law. Light cannot cohabit with darkness 4. 2 Corinthians 6:14-17 5. 2 Corinthians 10:1-6 ● Verse 6=Biblical definition of a Zealot 6. Isaiah 59:15-20 (Jesus/Yah is a Zealot) 7. Isaiah 9:6-7 8. Psalms 69:9 9. John 2:13-17 10. Psalms 51:1 (David) ● David prayed this after the sin of adultery and murder. How do you receive these tender mercies I.E. Yah doing you a solid? You got to be a day one with him. A zealot. David was willing to fight Yah’s battles literally. And he did so with faith and no fear. After defeating goliath he had to wait to become King. Henever wavered even with Saul constantly trying to kill him. -

Judaism: Pharisees, Scribes, Sadducees, Essenes, and Zealots Extremist Fighters Who Extremist Political Freedom Regarded Imperative

Judaism: Pharisees,Scribes,Sadducees,Essenes,andZealots © InformationLtd. DiagramVisual PHARISEES SCRIBES SADDUCEES ESSENES ZEALOTS (from Greek for “separated (soferim in ancient Hebrew) (perhaps from Greek for (probably Greek from the (from Greek “zealous one”) ones”) “followers of Zadok,” Syriac “holy ones”) Solomon’s High Priest) Evolution Evolution Evolution Evolution Evolution • Brotherhoods devoted to • Copiers and interpreters • Conservative, wealthy, and • Breakaway desert monastic • Extremist fighters who the Torah and its strict of the Torah since before aristocratic party of the group, especially at regarded political freedom adherence from c150 BCE. the Exile of 586 BCE. status quo from c150 BCE. Qumran on the Dead Sea as a religious imperative. Became the people’s party, Linked to the Pharisees, Usually held the high from c130 BCE Underground resistance favored passive resistance but some were also priesthood and were the Lived communally, without movement, especially to Greco-Roman rule Sadducees and on the majority of the 71-member private property, as farmers strong in Galilee. The Sanhedrin Supreme Sanhedrin Supreme or craftsmen under a most fanatical became Council Council. Prepared to work Teacher of Righteousness sicarii, dagger-wielding with Rome and Herods and Council assassins Beliefs Beliefs Beliefs Beliefs Beliefs • Believed in Messianic • Defined work, etc, so as • Did not believe in • Priesthood, Temple • “No rule but the Law – redemption, resurrection, to keep the Sabbath. resurrection, free will, sacrifices, and calendar No King but God”. They free will, angels and Obedience to their written angels, and demons, or were all invalid. They expected a Messiah to demons, and oral code would win salvation oral interpretations of the expected the world’s early save their cause interpretations of the Torah – enjoy this life end and did not believe in Torah resurrection. -

Pauline Epistles Overview

Session 1 of 15 Pauline Epistles Overview Pauline epistles Apostle of the Crucified Lord, Michael Gorman, 2004 is the main book I studied along with notes and references in the New Jerusalem Bible and my own class notes. Historical, literary, theological, and religious aspects of Paul’s letters to be covered 1. Pay attention to small details and grand themes - the themes inform the details and the details create the themes. This is the “hermeneutical (interpretative) circle.” 2. Six key words describe the frame of reference in which Paul is understood: a. Jewish b. Covenantal c. Narrative - salvation history from promise to ultimate fulfillment (eschatalogical) d. Countercultural e. Trinitarian f. Cruciform 3. Worked directly with Greek text; scriptural quotations come from New Revised Standard Version 4. Let’s engage Paul and his letters as the pastoral, spiritual, and theological challenge Paul intended his letters to be. Our driving question is: What does this letter urge the Church to believe, to hope for, and to do? Study Guide developed by Ginger Herrington, Director of Adult Formation, St. Mary Magdalene Catholic Church, 2021 Session 1 of 15 Pauline Epistles Overview Chapter 1: Paul’s Worlds 1. Greek-speaking (koine = common); born of Jewish parents of the tribe of Benjamin - a Pharisee of Second Temple Judaism; a Roman citizen under Caesar Augustus. Culture: Greek; Religion: Judaism; Political power: Romans. 2. Hellenization - most people of the time spoke, thought, and wrote in koine; Jews used Greek translation of Hebrew Scripture (Septuagint, LXX). Greek culture permeated the Mediterranean basin, but did not replace local customs - rather, Greek culture merged with each local community. -

Herod I, Flavius Josephus, and Roman Bathing

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts HEROD I, FLAVIUS JOSEPHUS, AND ROMAN BATHING: HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY IN DIALOG A Thesis in History by Jeffrey T. Herrick 2009 Jeffrey T. Herrick Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts August 2009 The thesis of Jeffrey T. Herrick was reviewed and approved* by the following: Garrett G. Fagan Associate Professor of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies and History Thesis Advisor Paul B. Harvey Associate Professor of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies, History, and Religious Studies, Head of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Ann E. Killebrew Associate Professor of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies, Jewish Studies, and Anthropology Carol Reardon Director of Graduate Studies in History; Professor of Military History *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT In this thesis, I examine the historical and archaeological evidence for the baths built in late 1st century B.C.E by King Herod I of Judaea (commonly called ―the Great‖). In the modern period, many and diverse explanations of Herod‘s actions have been put forward, but previous approaches have often been hamstrung by inadequate and disproportionate use of either form of evidence. My analysis incorporates both forms while still keeping important criticisms of both in mind. Both forms of evidence, archaeological and historical, have biases, and it is important to consider their nuances and limitations as well as the information they offer. In the first chapter, I describe the most important previous approaches to the person of Herod and evaluate both the theoretical paradigms as well as the methodologies which governed them. -

Zealots and Pharisees

ZEALOTS AND PHARISEES 3rd Core Principle: The best criticism of the bad is the practice of the better. Oppositional energy only creates more of the same. (emphasis) There seems to be two common avoidances of conversion or transformation, two typical diversionary tactics that we humans use to avoid holding the pain: fight or flight. The way of fight is what I’ll call the way of Simon the zealot—and often the way of the cultural liberal. These folks want to change, fix, control, and reform other people and events. The zealot is always looking for the evil, the political sinner, the unjust one, the oppressor, the bad person over there. The zealot permits himself or herself righteously to attack them, to hate them, even to kill them. And when they do, they think they are “doing a holy duty for God” (John 16:2). You can take it as a general rule that when you don’t transform your pain you will always transmit it. Zealots and contemporary liberals often have the right conclusion, but their tactics and motives are often filled with self, power, control and the same righteousness they hate in conservatives. Basically, they want to do something to avoid holding the pain until it transforms them. Because of this too common pattern, I have come to mistrust almost all righteous indignation and moral outrage. In my experience, it is hardly ever from God. “Resurrected” people prayerfully bear witness against injustice and evil—but also agree compassionately to hold their own complicity in that same evil. It is not over there, it is here. -

Josephus' Jewish War and the Causes of the Jewish Revolt: Re-Examining Inevitability

JOSEPHUS’ JEWISH WAR AND THE C AUSES OF THE JEWISH REVOLT: RE-EXAMINING INEVITABILITY Javier Lopez, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2013 APPROVED: Christopher J. Fuhrmann, Major Professor Ken Johnson, Committee Member Walt Roberts, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Lopez, Javier. Josephus’ Jewish War and the Causes of the Jewish Revolt: Re-Examining Inevitability. Master of Arts (History), December 2013, 85 pp., 3 tables, 3 illustrations, bibliography, 60 titles. The Jewish revolt against the Romans in 66 CE can be seen as the culmination of years of oppression at the hands of their Roman overlords. The first-century historian Josephus narrates the developments of the war and the events prior. A member of the priestly class and a general in the war, Josephus provides us a detailed account that has long troubled historians. This book was an attempt by Josephus to explain the nature of the war to his primary audience of predominantly angry and grieving Jews. The causes of the war are explained in different terms, ranging from Roman provincial administration, Jewish apocalypticism, and Jewish internal struggles. The Jews eventually reached a tipping point and engaged the Romans in open revolt. Josephus was adamant that the origin of the revolt remained with a few, youthful individuals who were able to persuade the country to rebel. This thesis emphasizes the causes of the war as Josephus saw them and how they are reflected both within The Jewish War and the later work Jewish Antiquities. -

Jesus and the Zealots a Study of the Political Factor in Primitive Christianity

SICARRI ACTIONS AGAINST ROME Jesus and the zealots A Study of the Political factor in Primitive Christianity (formerly at http://www.geocities.com/aleph135/zealots.html?20089) S.G.F.Brandon M.A. D.D.Professor of comparitive religion in the University of Manchester, Manchester Univ press, 1967. The following extracts are some of the main factors in the problem of historical tradition regarding early Christian origins and early Christian beliefs. Brandon covers the topic well and reveals some of the major problems regarding church history. Historical evidence from this period contradicts later church history based upon disinformation and a lack of historical evidence in the NT relating to the destruction of Jerusalem by Titus, on Aug 29 AD.70; and the later capture of Masada in AD.73 and the destruction and the deportation of the Zealot factions by the 10th Legion after a two year siege. The main thrust here is that political forces were the major factors in these developments as the Zealots were attempting to overthrow Roman rule in Judea. Zealots were known as the (kanaim) in Aramaic, or Sicarri = Latin for sikariwn, lestwn in Gk, meaning brigands in the common terminology of the Romans but more accurately we would call them revolutionaries or terrorists as they were attempting to overthrow Roman rule. The Sicarri were called this on account of their short daggers known in Gk. as mikra zifidia Rabbinic sources refer to the; in Hebrew, ( sikarim) during the siege of Jerusalem. Josephus equates the lestai as Sicarri the term Zhlwths is not a Heb word it is Gk. -

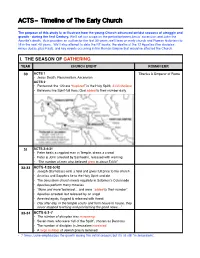

WBW | P.2 | Timeline of Acts | Notes

ACTS- Timeline of The Early Church The purpose of this study is to illustrate how the young Church advanced amidst seasons of struggle and growth - during the first Century. We’ll set our scope on the period between Jesus’ ascension and John the Apostle’s death. Acts provides an outline for the first 30 years; we’ll lean on early church and Roman historians to fill in the next 40 years. We’ll also attempt to date the NT books, the deaths of the 12 Apostles (the disciples minus Judas, plus Paul), and key events occurring in the Roman Empire that would’ve affected the Church. I. THE SEASON OF GATHERING YEAR CHURCH EVENT ROMAN EMP. 30 ACTS 1 Tiberius is Emperor of Rome • Jesus Death, Resurrection, Ascension ACTS 2 • Pentecost: the 120 are “baptized” in the Holy Spirit; 3,000 believe • Believers live Spirit-full lives; God added to their number daily 31 ACTS 3-4:31 • Peter heals a crippled man in Temple, draws a crowd • Peter & John arrested by Sanhedrin, released with warning • “The number of men who believed grew to about 5,000” 32-33 ACTS 4:32-5:42 • Joseph (Barnabas) sells a field and gives full price to the church • Ananias and Sapphira lie to the Holy Spirit and die • The Jerusalem church meets regularly in Solomon’s Colonnade • Apostles perform many miracles • “More and more” believed… and were “added to their number” • Apostles arrested, but released by an angel • Arrested again, flogged & released with threat • Day after day, in the temple courts and from house to house, they never stopped teaching and proclaiming the good news…” 33-34 ACTS 6:1-7 • The number of disciples was increasing • Seven men, who were “full of the Spirit”, chosen as Deacons • The number of disciples in Jerusalem increased • A large number of Jewish priests believed • 7 times, Luke emphasizes the growth during this initial season; but it’s all still “in Jerusalem”. -

Visions of Apocalypse: What Jews, Christians, and Muslims Believe

May 2010 Visions of Apocalypse What Jews, Christians, and Muslims Believe about the End Times, and How Those Beliefs Affect Our World An essay on comparative eschatology among the three Abrahamic faiths—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—and how beliefs about the end times express themselves through foreign policy and conflict By Robert Leonhard STRATEGIC ASSESSMENTS NATIONAL SECURITY ANALYSIS DEPARTMENT THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY • APPLIED PHYSICS LABORATORY 11100 Johns Hopkins Road, Laurel, Maryland 20723-6099 The creation of this monograph was sponsored by the Strategic Assessments Project within the National Security Analysis Department of The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL). Its ideas are intended to stimulate and provoke thinking about national security issues. Not everyone will agree with the premises put forward. It should be noted that this monograph reflects the views of the author alone and does not imply concurrence by APL or any other organization or agency. Table of Contents Preface………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……………Page 3 Chapter 1: Prophecy and Interpretation ………………………………………………….…………………Page 10 Chapter 2: Mélekh ha-Mashíah (The Anointed King): Judaism and the End Times…......Page 21 Chapter 3: Thy Kingdom Come: Christianity and the End Times…………………….…………….Page 54 Chapter 4: The Awaited One: Islam and the End Times……………………………….………..…….Page 102 Chapter 5: Conclusion: The Crucible of Prophecy……………………………………………………....Page 121 2 PREFACE On the slopes of the Mount of Olives, east of Jerusalem and within sight of both the Temple Mount and the al-Aqsa Mosque, lie 150,000 Jewish graves dating from ancient times through today. Many of the bodies are buried with their feet toward the city, because ancient prophets declared that the resurrection would begin there, and the faithful would rise and follow the Messiah into the Holy City.