Framework of the Paper on Higher Education in Tamil Nadu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Society of Indiatm

TM TM Computer Society of India TM 50th Annual Report 2014-15 50th Annual Report 2014-2015 Registered Office Contents COMPUTER SOCIETY OF INDIA 302, Archana Arcade, 10-3-190, St. Johns Road, Secunderabad – 500025 Executive Committee 1 Tel. : 040-27823123 2014-2015 & 2015-2016 Head Office Unit No.3, 4th Floor Samruddhi Venture Park Annual Report 2 MIDC, Andheri (E), Mumbai 400 093 Email : hq@ csi-india.org Chapters 6 Tel. : 022 2926 1700 website : http//www.csi-india.org Region's Activities 7 Education Directorate CPT Campus, Taramani Chennai-600 113 Education Directorate 48 Tel./Fax : 044-2254 2874 Activity Report Email : [email protected] Auditors Division/Chapter/SIG/ 50 M/s. Pruthviraj Shah & Co. ED Activity Report Bankers to Head Office State Bank of India Central Bank of India Education Directorate 58 Standard Chartered Bank Axis Bank List of Student Branches 60 Bankers to Education Directorate State Bank of India CSI Gold Tech Bridge Programme 88 Axis Bank 50th Annual Report 2014-2015 Computer Society of India Executive Committee 2014-2015 2015-2016 Mr. H R Mohan President Prof. Bipin V. Mehta President Prof. Bipin V Mehta Vice-President Dr Anirban Basu Vice-President Mr. Sanjay Mohapatra Hon. Secretary Mr. Sanjay Mohapatra Hon. Secretary Mr. Ranga Rajagopal Hon. Treasurer Mr. R. K. Vyas Hon. Treasurer Prof. S V Raghavan Immd. Past President Mr. H R Mohan Immd. Past President Mr. R K Vyas Regional Vice-President, Mr. Shiv Kumar Regional Vice-President, (Region I) (Region I) Mr Devaprasanna Sinha Regional Vice-President, Mr. Devaprasanna Sinha Regional Vice-President, (Region II) (Region II) Prof. -

Review Workshop for Resource Material in Earthquake Engineering for Faculty Members from Engineering Colleges Across India at IIT Kanpur During 26-30 April 2004

Department of Civil Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Review Workshop for Resource Material in Earthquake Engineering for Faculty Members from Engineering Colleges across India at IIT Kanpur during 26-30 April 2004 A Brief Report A five day Review Workshop for Resource Material in Earthquake Engineering sponsored by the National Programme on Earthquake Engineering Education (NPEEE), under MHRD is being organized at IIT Kanpur during 26-30 April 2004. Forty seven faculty members from different engineering colleges across the country (from 13 different states) participated in this workshop. The workshop was inaugurated by Professor Kripa Shanker, Deputy Director, IIT Kanpur. Professor Kripa Shanker commended the work being done by the earthquake engineering group at IIT Kanpur under the leadership of Professor Sudhir K. Jain, National Coordinator, NPEEE and Coordinator, NICEE. Professor Sudhir K. Jain informed the participants about the various NPEEE activities being conducted by IIT Kanpur and it’s counterparts (other 5 IIT’s) and Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore. Professor Satish C. Koria, Head, Centre for Development of Technical Education, IIT Kanpur briefed the participants about the ongoing activities at IIT Kanpur in the area of continuing education. During the workshop, the participants had discussions with faculty members of IIT Kanpur and one faculty member of IIT Madras, who specialize in earthquake engineering apart from other activities like video shows on past great earthquakes, and visits to state- of-the art Forced Vibration Test Facility, Structural Engineering Laboratory, and National Wind Tunnel Test facility (copy of workshop schedule is enclosed). All the participants took active part in the workshop and about 87,000 pages of information were photocopied by the participants during the workshop. -

PALANI.S CURRICULUM VITAE NSS Programme Officers(Ten Years)

CURRICULUM VITAE Career Objective To work on ambitious assignments in a stimulating environment that nurtures creative professional growth while being resourceful, innovative and flexible. Educational Qualification Ph.D: Madurai Kamaraj University (2015) Topic:"INEQUALITIES IN HEALTH CARE ACCESS AND PATTERN OF HEALTH CARE EXPENDITURE IN TAMIL NADU WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO MADURAI DISTRICT" PALANI.S M.phil:Madurai Kamaraj University (1991) Address: Associate Professor& Head Topic:CANARA BANK LOAN FOR DAIRY DEVELOPMENT WITH Dept. of Economics, SPECIAL REFERENCE TO USILAMPATTI BLOCK IN MADURAI DISTRICT. MTN College, Pasumalai M.A: History Madurai Kamaraj University (1995) Madurai-04. B.Ed. : Economics Madurai Kamaraj University (1993) M.A :EconomicsArul AnandarCollege, Madurai (1990) Mobile: 9894458382 B.A:PasumponMuthuramalingaThevar College, Usilampatti, Email: [email protected] Madurai, Tamilnadu. (1988) Teaching Experience( 25 Years) Personal Details: Assistant Professor (1995 -2000) DOB : 03/12/1965 MuthuramalingaThevar College, Usilampatti,Madurai, Tamilnadu Sex :Male Nationality :Indian At present working as an Associate Professor of Economics, MTN College, Religion : Hindu Madurai -04.(Since 2000) Marital Status :Married NSS programme officers(Ten Years) Personal Skills: 10 year (2000 – 2009). Interpersonal skills. Chief Superintendent: Compatible nature. Quick Learner 2013-2016 (Madurai Kamaraj University Semester Examinations And UPSC, SLET, Go-getter. RAILWAY,BANKING, TNPSC EXAMS were conducted. Hobbies: Foreign visit: 1. Thailand , 30/09/2016 Listening music. 2. Sharjah ,Dubai 9/11/2019 to 13/11/2019 Surfing Internet. Languages Known: Number of Awards Received English. Tamil. 1. Best presentor award :( Thailand) International Conference Areas of Interest: 2. Best Economist Award :( Goa) International Conference Development 3. Senior Economist Award :(Trichy) Association of Economist Tamil Nadu (2019) Economics Health Economics 4. -

Tamil Nadu State Research Report on Working Conditions of Elementary and Secondary School Teachers

NUEPA Research Reports Publications Series Teachers in the Indian Education System Tamil Nadu State Research Report on Working Conditions of Elementary and Secondary School Teachers Guide Dr. S. Kannappan Director, SCERT, Chennai Principal Researcher J. Inbaraj, M.A., M.Ed., M.Phil Reader, SCERT, Chennai Research Assistant S.Manivel, M.Sc. M.Ed., M.Phil Reader, SCERT, Chennai National University of Educational Planning and Administration New Delhi NRRPS/001(4/9)/2016 NRRPS/001/(4/9)/2016 NUEPA Research Reports Publications Series Teachers in the Indian Education System Tamil Nadu State Research Report on Working Conditions of Elementary and Secondary School Teachers (A NUEPA - SCERT Joint Project) Guide Dr. S. Kannappan Director, SCERT, Chennai Principal Researcher J. Inbaraj, M.A., M.Ed., M.Phil Reader, SCERT, Chennai Research Assistant S. Manivel, M.Sc., M.Ed., M.Phil Reader, SCERT, Chennai National University of Educational Planning and Administration New Delhi i © National University of Educational Planning and Administration, 2016 (Declared by Government of India under Section 3 of the UGC Act, 1956) June 2016 (PDF) Disclaimer: The research report has not been evaluated by any external expert, and also not edited by the PMU, NUEPA. The views and opinions expressed in the research report are those of the author(s)/editor(s) and should not be attributed to NUEPA. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronics, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without permission in writing from NUEPA. ii Acknowledgments First and foremost, the research team would like to convey their gratitude to the Ms. -

ET CAMPUS STARS Following Candidates Have Been Shortlisted for Phase 3 of ET Campus Stars

ET CAMPUS STARS Following candidates have been shortlisted for Phase 3 of ET Campus Stars. Please feel free to reach out to us at [email protected] in case of any query. NAME BRANCH COLLEGE AADI MANIKANTA PADAMATA ELECTRONICS AND COMMUNICATION ENGINEERING DHANEKULA INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERINGAND TECHNOLOGY, VIJAYAWADA AASHAY GURAV MECHATRONICS ENGINEERING TERNA ENGINEERING COLLEGE, MUMBAI ABHIGYAN SRIVASTAV TEXTILE TECHNOLOGY IIT DELHI ABHIK SARKAR ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING ACADEMY OF TECHNOLOGY, HOOGHLY ABHINANDAN SHAH INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY VADODARA INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING, VADODARA ABHINAV KINGER INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY MAHARAJA AGRASEN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, DELHI ABHINAV SREESAN ELECTRONICS AND TELECOMMUNICATIONS ENGINEERING S.I.E.S. GRADUATE SCHOOL OF TECHNOLOGY, MUMBAI ABHIPSA MISHRA COMPUTER SCIENCE ENGINEERING COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY, BHUBANESHWAR ABHISHEK BHATTACHARYA MECHANICAL ENGINEERING RUNGTA COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY, BHILAI ABHISHEK DHOBE CHEMICAL ENGINEERING NIT NAGPUR ABHISHEK GAUTAM COMPUTER SCIENCE ENGINEERING G L BAJAJ GROUP OF INSTITUTIONS, NOIDA ABHISHEK GUPTA MECHANICAL ENGINEERING NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY BRAHMAPUR, BRAHMAPUR ABHISHEK MURARAKA CHEMICAL ENGINEERING IIT GUWAHATI ABHISHEK NEGI COMPUTER SCIENCE ENGINEERING DEHRADUN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, DEHRADUN ABHISHEK RAWAT ELECTRICAL AND ELECTRONICS ENGINEERING MAHARAJA AGRASEN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, DELHI ABHISHEK VASUDEV INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY NORTHERN INDIA ENGINEERING COLLEGE, DELHI ADARSH SAVANT MECHANICAL -

Region 10 Student Branches

Student Branches in R10 with Counselor & Chair contact August 2015 Par SPO SPO Name SPO ID Officers Full Name Officers Email Address Name Position Start Date Desc Australian Australian Natl Univ STB08001 Chair Miranda Zhang 01/01/2015 [email protected] Capital Terr Counselor LIAM E WALDRON 02/19/2013 [email protected] Section Univ Of New South Wales STB09141 Chair Meng Xu 01/01/2015 [email protected] SB Counselor Craig R Benson 08/19/2011 [email protected] Bangalore Acharya Institute of STB12671 Chair Lachhmi Prasad Sah 02/19/2013 [email protected] Section Technology SB Counselor MAHESHAPPA HARAVE 02/19/2013 [email protected] DEVANNA Adichunchanagiri Institute STB98331 Counselor Anil Kumar 05/06/2011 [email protected] of Technology SB Amrita School of STB63931 Chair Siddharth Gupta 05/03/2005 [email protected] Engineering Bangalore Counselor chaitanya kumar 05/03/2005 [email protected] SB Amrutha Institute of Eng STB08291 Chair Darshan Virupaksha 06/13/2011 [email protected] and Mgmt Sciences SB Counselor Rajagopal Ramdas Coorg 06/13/2011 [email protected] B V B College of Eng & STB62711 Chair SUHAIL N 01/01/2013 [email protected] Tech, Vidyanagar Counselor Rajeshwari M Banakar 03/09/2011 [email protected] B. M. Sreenivasalah STB04431 Chair Yashunandan Sureka 04/11/2015 [email protected] College of Engineering Counselor Meena Parathodiyil Menon 03/01/2014 [email protected] SB BMS Institute of STB14611 Chair Aranya Khinvasara 11/11/2013 [email protected] -

Annual Report

THE INSTITUTE OF MATHEMATICAL SCIENCES C. I. T. Campus, Taramani, Chennai - 600 113. ANNUAL REPORT Apr 2015 - Mar 2016 Telegram: MATSCIENCE Telephone: +91-44-22543100,22541856 Fax:+91-44-22541586 Website: http://www.imsc.res.in/ e-mail: offi[email protected] Foreword The Institute of Mathematical Sciences, Chennai has completed 53 years and I am pleased to present the annual report for 2015-2016 and note the strength of the institute and the distinctive achievements of its members. Our PhD students strength is around 170, and our post-doctoral student strength is presently 59. We are very pleased to note that an increasing number of students in the country are ben- efiting from our outreach programmes (for instance, Enriching Mathematics Education, FACETS 2015, Physics Training and Talent Search Workshop) and we are proud of the efforts of our faculty, both at an individual and at institutional level in this regard. IMSc has started a monograph series last year, with a plan to publish at least one book every year. A book entitled “Problems in the Theory of Modular Forms” as ‘IMSc Lecture Notes - 1’ has been published this year Academic productivity of the members of the Institute has remained high. There were several significant publications reported in national and international journals and our faculty have authored a few books as well. Five students were awarded Ph.D., and three students have submitted their Ph.D. theses. Four students were awarded M.Sc. by Research, and two students have submitted their master’s theses under the supervision of our faculty. -

Tamilnadu Engineering Admissions 2017

TAMILNADU ENGINEERING ADMISSIONS 2017 jkpo;ehL nghwpapay; Nrh;f;if 2017 INFORMATION ABOUT THE COLLEGES fy;Y}hpfs; gw;wpa jfty; NOTE TO THE CANDIDATES 1. The details given in this booklet are as received from the colleges concerned. 2. The tuition fee will be collected as per Government norms. 3. The hostel charges and transportation charges are given in this booklet. The candidates are advised to note these charges before making a choice. 4. Request for change from one college to another or change of branch will not be entertained. 5. Some of the colleges have not furnished complete information. Those colleges may be contacted directly, if the candidates so desire. 6. The courses / branches indicated in this booklet are based on the supporting documents such as AICTE approval and University affiliation. Any change in the existing branches / intake or if approval is obtained from the competent authority for additional intake in the existing branches or for any new branches in colleges before the commencement of counselling, such of those details will be hosted in Anna University website and included in the display during counselling. It is the responsibility of the candidates to note carefully such additional information before exercising their option for the college and branch. 7. Mere inclusion in the booklet does not entitle the college to be included in the single window counselling for TNEA 2017. LIST OF COLLEGES Sl. TNEA Page Name of the College No. Code No. No. UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENTS 1 0001 University Departments of Anna University, -

Annexure Government of India Ministry of Science & Technology, Department of Science & Technology List of Selected Stude

Annexure 12011/32/2010 INSPIRE (Tamil Nadu) Dated: 25 Oct 2018 Government of India Ministry of Science & Technology, Department of Science & Technology List of Selected Students under the INSPIRE Award Scheme for the Year 2018-19 Name of the State :Tamil Nadu No. of Sanctioned :3275 Sr. Name of Name of Name of Sub Name of the School Name of the selected Class Sex Category Name of Father UID No Ref Code No. Revenue Education District Student or Mother District District (Block/Tehsil/Zone etc.) 1 Ariyalur ARIYALUR Ariyalur PANCHAYAT UNION DURGADEVI S 7 F OBC SIVAKUMAR 18TN1467706 MIDDLE SCHOOL 2 Ariyalur ARIYALUR Ariyalur PANCHAYAT UNION DHANUSH G 8 M OBC GANACHANDRAN 18TN1467707 MIDDLE SCHOOL 3 Ariyalur Ariyalur Ariyalur GOVERNMENT HIGH S. REETA 10 F OBC SELVAKUMAR 18TN1467708 SCHOOL KANDARATHITHAM 4 Ariyalur Ariyalur Ariyalur GOVERNMENT HIGH S RETHINAM 9 M OBC SURIYARAJAN 18TN1467709 SCHOOL KANDARATHITHAM 5 Ariyalur Ariyalur Ariyalur GOVERNMENT HIGH G NARMATHA 8 F OBC GUNASEKAR 18TN1467710 SCHOOL KANDARATHITHAM 6 Ariyalur Ariyalur Ariyalur GOVERNMENT HIGH P. MANON 7 F OBC PALANISAMY 18TN1467711 SCHOOL KANDARATHITHAM 7 Ariyalur Ariyalur Ariyalur GOVERNMENT HIGH K PARIMALA 6 F OBC KANNAN 18TN1467712 SCHOOL KANDARATHITHAM Page 1 of 243 Sr. Name of Name of Name of Sub Name of the School Name of the selected Class Sex Category Name of Father UID No Ref Code No. Revenue Education District Student or Mother District District (Block/Tehsil/Zone etc.) 8 Ariyalur ARIYALUR Ariyalur GOVERNMENT Velmurugan E 8 M OBC Eruthayaraj 18TN1467713 HIGHER SECONDARY -

Policy Note of School Education Department

POLICY NOTE 2015-2016 CONTENTS I Policy 1 II Financial Outlay 10 III Polices and Schemes 1. Welfare Schemes 12 2. Elementary Education and 24 Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan 3. Secondary and Higher 121 Secondary Education and Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan 4. Matriculation Schools 184 5. Government Examinations 195 6. Non-formal and Adult 212 Education 7. Public Libraries 221 8. State Council of Educational 255 Research and Training 9. Teachers’ Recruitment Board 284 10. Tamilnadu Textbook and 296 Educational Services Corporation (i) LIST OF GRAPHS AND PICTURES SI. Details Page No. No. GRAPHS 1. Dropout Rate (Primary, Upper Primary & 2 Secondary) 2. Net Enrolment Rate (NER) 42 3. Dropout Rate (Primary & Upper Primary) 43 4. Completion Rate (CR) 44 5. Gender Perspective in enrolment - 45 Primary 6. Gender Perspective in enrolment - Upper 46 primary 7. Teacher Pupil Ratio (TPR) 47 8. Retention Rate 48 9. Out of School Children identified and 50 enrolled 10. Simplified Activity Based Learning 71 (SABL) 11. Active Learning Methodology (ALM) 73 12. Comparison of attendance of students 74 above 80% (2013-2014 & 2014-2015) 13. Comparison of Co-scholastic 75 performance of Class V (2013-2014 & 2014-2015) 14. Comparison of CCE Scholastic 75 performance Class VII (2013-2014 & 2014-2015) 15. Assessment - Primary - Comparison of 77 basic skills 16. Assessment - Upper Primary - 78 Comparison of basic skills 17. SLAS- Comparison of % of children 80 secured above 50 % - Class III 18. SLAS- Comparison of % of children 81 secured above 50 % - Class V 19. SLAS- Comparison of % of children 81 secured above 50 % - Class VIII 20. -

School Educational Status of Tamilnadu- a Case Study

Vol. 1 No.2 March 2013 ISSN : 2320 –2653 SCHOOL EDUCATIONAL STATUS OF TAMILNADU- A CASE STUDY Dr (Mrs) M. CHITRA Department Of Econometrics, Madurai Kamaraj University, Madurai Dr. S. NAGARAJAMURUGAN Chief Educational Officer, Tamil Nadu Abstract Education is an engine of social and economic development. Investment in education as time and money will give the fruitful to the society then and there. The positive externality will be created if the output of education system is good. The supply side the government intervene in educational sector to create a positive externality in all aspects, in that sense in VirudhuNagar district (which is well known in internationally for its fireworks) is tested for its school educational status. The output of school education shown that the government sector played a vital role more than the private sector in VirudhuNagar District. Key words: School Education, S.S.L.C and Perception. Introduction Education is a critical invasive instrument for bringing about social, economic and political inclusion and a durable integration of people, particularly those excluded from the mainstream of any society. Indian education system was thrown open too all rich, poor and middle income classes, men and women, rural and urban population, and backward and non-backward segments of the population at all levels. As a consequence, there has been a veritable explosion in numbers – student numbers, institutions, and teachers. The returns to education may vary across individuals, regions, level and nature of education; in general, they are significantly higher for poor developing areas than for rich. Education is therefore his best social investment, given the synergies and the positive externalities that it generates for people in their well-being. -

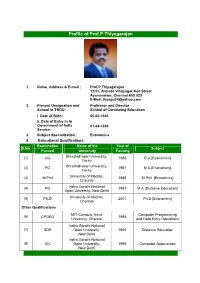

Profile of Prof.P.Thiyagarajan

Profile of Prof.P.Thiyagarajan 1. Name, Address & E-mail : Prof.P.Thiyagarajan 12/31, Ananda Vinayagar Koil Street Ayanavaram, Chennai-600 023 E-Mail: [email protected] 2. Present Designation and Professor and Director School in TNOU: School of Continuing Education i. Date of Birth: 05-03-1963 ii. Date of Entry in to Government of India 01-04-1989 Service: 3. Subject Specialization : Economics 4. Educational Qualifications: Examination Name of the Year of S.No. Subject Passed University Passing (1) UG Bhrathidhasan University, 1985 B.A.[Economics] Trichy (2) PG Bhrathidhasan University, 1987 M.A.[Economics] Trichy (3) M.Phil University of Madras, 1988 M.Phil. [Economics] Chennai (4) PG Indira Gandhi National 1997 M.A.[Distance Education] Open University, New Delhi (5) Ph.D University of Madras, 2001 Ph.D [Economics] Chennai Other Qualifications MIT-Campus, Anna Computer Programming (6) CPDEO 1988 University, Chennai and Data Entry Operations Indira Gandhi National (7) DDE Open University, 1993 Distance Education New Delhi Indira Gandhi National (8) CIC Open University, 1999 Computer Applications New Delhi 1 5. Employment History Appointed as Statistician by Directorate of Economic Research, Khadi and Village Industries Commission (KVIC), Irla Road, Vile Parle(West), Bombay-400056 vide Lr.No. EST/ECR/DSSC-I/88-89 dated 14/03/1989 and Joined in KVIC, State Office, Trivandrum -695001 on 01/04/1989. (Scale of Pay:Rs.1350-Rs.2200) Appointed as Investigator by Staff Selection Commission (SSC), Government of India, Ministry of Planning, Department of Statistics, National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO), New Delhi vide Lr.No. A.11010/1/Admn/TNN/89 dated 06/09/1989 and Joined in NSSO, Shastri Bhavan , Madras-600006 on 18/09/1989.