Bangalore Cluster: Evolution, Growth and Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the Adjudications Rendered by the Council in Its Meeting Held on 17.3.2016

Press Council of India Index of the Adjudications rendered by the Council in its meeting held on 17.3.2016 Complaints Against the Press Section-14 Inquiry Committee-I Meeting held at Guwahati, Assam December 9-10, 2015 1. Complaint of Shri Brijesh Mishra, Advocate, Tinsukia, Assam against the Editor, Dainik Janambhumi, Assam. (14/486/13-14) 2. Complaint of Shri Sourav Basu Roy Choudhury, Agartala, West Tripura against the Editor, Pratibadi Kalam, Agartala. (14/922/13-14-PCI) 3. Complaint of Dr. Binod Kumar Agarwala, Prof. & Head, Department of Philosophy, North Eastern Hill University, Shillong against the Editor, The Shillong Times, Shillong (14/175/14-15-PCI) 4. COMPLAINT OF COL. SANJAY & LIEUTENANT COLONEL SOORAJ S. NAIR, ASSAM RIFLES AGAINST THE EDITOR, TEHELKA, NEW DELHI. (14/672/14-15) 5. COMPLAINT OF SHRI SHYAMAL PAL, GANGTOK(RECEIVED THROUGHSHRI K. GANESHAN, DIRECTOR GENERAL, DAVP) AGAINST HIMALI BELA, GANGTOK (14/117/15-16) 6. Complaint of Shri Randhir Nidhi, Jharkhand against the Editor, Ranchi Express, Ranchi. (14/618/12-13) 7. Complaint of Shri Praveen Chandra Bhanjdeo, MLA, Odisha Legislative Assembly, Bhubaneswar against the Editor, Nirbhay. (14/716/13-14) 8. Complaint of Dr. Nachiketa Banopadhyay, Registrar, Siodho-Konho-Birsa University, Kolkata against the Editor, Sambad Protidin. (14/734/13-14) 9. Shri Nilabh Dhruva, Manager Legal, Bihar Urban Infrastructure, Patna, Bihar against the Editor, Hindustan. (14/1038/13-14) 10. Complaint of Shri Thakur Chandra Bhushan, Honorary Secretary, Outgoing Management, Deep Sahkari Grin Nirman Samiti, Jamshedpur (Jharkhand) against the Editor, Hindustan, Jamshedpur. (14/1/14-15) 11. COMPLAINT OF SHRI SAMEER KUMAR DA, CHIEF ENGINEER, HIND KI KALAM, CO- DIRECTOR, STATE PROGRAMME MANAGEMENT UNIT, DRINKING WATER & SANITATION DEPARTMENT, JHARKHAND, RANCHI AGAINST THE EDITOR, DAINIK BHASKAR, RANCHI, JHARKHAND. -

A Study of Rural Women in Karnataka State

www.ijcrt.org © 2018 IJCRT | Volume 6, Issue 1 February 2018 | ISSN: 2320-2882 Evaluation of newspapers as information supporting agencies: A study of rural women in Karnataka state 1Shobha Patil and 2P. G. Tadasad 1UGC-Post Doctoral Fellow, Department of Library and Information Science, Akkamahadevi Women’s University, Vijayapura, Karnataka 2Professor and Chairman, Department of Library and Information Science, Akkamahadevi Women’s University, Vijayapura, Karnataka Abstract: The present work is an effort to know the evaluation of newspapers as an information supporting agency among rural women in Karnataka state. Data was collected on newspaper readers and Usefulness of newspaper as information supporting agency. A sample size of 1800 rural women was taken for the study, the research identifies the general characteristics of study population, newspaper reading habits of women, preferred places for reading newspapers, categories of newspapers read by rural women, list of daily newspapers read by women, purpose of reading newspapers, newspapers as an information supporting agency and usefulness of newspapers as information supporting agency. Concludes that the onus is on libraries to prove their significance. Keywords: Newspaper, Periodical, Rural Women, Karnataka 1. Introduction: Newspapers, magazines and books are a good means of mass-communication. This is a print medium which travels far and wide. The newspapers have a very wide circulation and every literate person tries to go through them. They bring us the latest news, rates of the commodities, advertisements, employment news, matrimonial and other information [1]. Newspapers tend to reach more educated, elitist audiences in many developing countries. This may not seem the quickest way, compared with radio or TV, to reach a mass audience. -

JNANA - Pure Knowledge

JNANA - Pure Knowledge To know that you don't know is the real knowledge PART I (Collection of blog articles from 2005 - 2007) Krishna Raj P M Apr 2011 Page 1 of 366 This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 2.5 India Licence You are free ➔ to Share: to copy, distribute and transmit the work ➔ to Remix: to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work) Noncommercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes With the understanding that: Waiver: Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder Other Rights: In no way are any of the following rights affected by the license • Your fair dealing or fair use rights; • The author’s moral rights; • Rights other persons may have either in the work itself or in how the work is used, such as publicity or privacy rights. Notice: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. Page 2 of 366 GATS and its implication on higher education in India After opening up various sectors like banking, insurance and communication to Multi National Companies, the Indian Government has decided to open up the education sector for them. Finally, globalisation and commercialisation of education is becoming a reality. General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), which came into force in 1996, provides legal rights to trade in all services except those taken care of entirely by the government. -

Tabloidization of the Media: the Page Three Syndrome* Justice G.N

Tabloidization of the Media: The Page Three Syndrome* Justice G.N. Ray C.P. Scott, the founder editor of the Manchester Guardian, once said: "News is sacred, opinion is free". In India, news in a written format had always been considered the truth and has been more powerful than the spoken word. But such position is not anymore. Media is an integral and imperative component of democratic polity and is rightly called fourth limb of democracy. It is not merely what the media does in a democracy, but what it is, that defines the latter. Its practice, its maturity, and the level of ethics it professes and practices in its working are as definitive of the quality of a democracy as are the functions of the other limbs. With tremendous growth and expansion, prospects of mass media are today viewed as more powerful than ever before. However some feel that the media has gone too far ahead of itself, and today media has become more show rather than the medium. Media has created its own world of glamour, gossip, sex and sensation, that has played a major role in distracting attention from the real issues of our times. Former Chief Vigilance Commissioner N. Vittal in his article in Bhavan's journal June 30, "Journalism is losing……" has indicated that special problem faced by journalists these days relates to journalism itself. The page 3 culture can make people live in a make-believe world and as a result, instead of journalism connecting people, it may result in the people losing touch with reality being connected through the media. -

Clampdowns and Courage South Asia Press Freedom Report 2017-2018

CLAMPDOWNS AND COURAGE SOUTH ASIA PRESS FREEDOM REPORT 2017-2018 SIXTEENTH ANNUAL SOUTH ASIA PRESS FREEDOM REPORT (2017-2018) 2 IFJ PRESS FREEDOM REPORT 2017–2018 3 CONTENTS This document has been produced Cover Photo: Students and activists 1. FOREWORD 4 by the International Federation of holding ‘I am Gauri’ placards take part Journalists (IFJ) on behalf of the in a rally held in memory of journalist 2. OVERVIEW 6 South Asia Media Solidarity Network Gauri Lankesh in Bangalore, India, (SAMSN). on September 12, 2017. The murder Afghan Independent Journalists’ of Gauri Lankesh, a newspaper editor Association and outspoken critic of the ruling SPECIAL SECTIONS Hindu nationalist party sparked an Bangladesh Manobadhikar outpouring of anger and demands Sangbadik Forum for a thorough investigation. CREDIT: 3. IMPUNITY 10 Federation of Nepali Journalists MANJUNATH KIRAN / AFP Free Media Movement, Sri Lanka 4. RURAL JOURNALISTS 18 Indian Journalists’ Union This spread: Indian journalists take part in a protest on May 23, 2017 Journalists Association of Bhutan after media personnel were injured 5. GENDER - #METOO AND 26 Media Development Forum Maldives covering clashes in Kolkata between National Union of Journalists, India police and demonstrators who were THE MEDIA National Union of Journalists, Nepal calling for pricing reforms in the Nepal Press Union agriculture sector. CREDIT: DIBYANGSHU 6. INTERNET SHUTDOWNS 32 Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists SARKAR/AFP Sri Lanka Working Journalists’ Association This document has been produced with support from the United Nations COUNTRY CHAPTERS South Asia Media Solidarity Educational, Scientific and Cultural Network (SAMSN) – Defending Organisation (UNESCO) and the rights of journalists and freedom of 7. -

Creative Industries, the Way Forwad

CREATIVE INDUSTRIES, THE WAY FORWARD S.V.Srinivas, P.Radhika, and Ashish Rajadhyaksha with inputs from K.Sravanthi CIDASIA, Centre for the Study of Culture and Society December 2009 INTRODUCTION The project proposes to study indigenous non-traditional cultural production or what has come to be referred to as ‘creative industries’ (e.g. media, audio-visual industry, film, television) in recent times.1 By creative industries we refer to the vast sector that has emerged with the arrival of modern technologies and forms of mass reproduction since the colonial period. This sector has now become an important site of intervention for both governments such as in UK, Australia and India and international agencies such as the United Nations. This study is a part of a larger CIDASIA initiative to research the area of what we call ‘culture industries’ that includes both ‘creative industries’ and ‘cultural industries’ (including crafts and legacy industries), focussing on the increasing areas of overlap between the two. The initiative attempts to assess the viability of international and government policies for cultural and creative industries and thus lay the groundwork for a hitherto unprecedented intervention of philanthropic organizations in the domain. We specifically focus on culture industries through the node of ‘livelihoods’ that we see as inextricably tied to this sector. In attempting to do so we will critically examine influential paradigms and frameworks that have in the recent past determined the response of the state as well as philanthropists in the broad area of arts and culture. The present study restricts itself to the creative industries sector, using the cases of film, print and music industries. -

An Evaluation of Kannada News Paper Websites Using Alexa Internet Tool: a Webometric Study

International Journal of Library and Information Studies Vol.8(1) Jan-Mar, 2018 ISSN: 2231-4911 An Evaluation of Kannada News Paper Websites Using Alexa Internet Tool: A Webometric Study S. Muthuraja Research Scholar Dept. of LIS Bangalore University JB Campus, Bangalore -56 Senior Scale Librarian Govt. First Grade College, Bukkapatna- 572 115 E-mail: [email protected] Prof. M. Veerabasavaiah Professor Department of Library and Information Science Bangalore University JB Campus, Bangalore -56. Emil:[email protected] Abstract - The present study has been done by using webometric methods. This paper intends to evaluate the Kannada language newspaper web sites using the most well known tool for evaluating websites “Alexa Internet” a company of Amazon.com. The 10 leading Kannada language newspaper websites from the state of Karnataka were taken for evaluation. Each newspaper web site was searched in Alexa databank and relevant data including traffic rank, pages viewed, speed, links, and bounce percentage, time on site, search percentage, and percentage of Indian/foreign users were collected and these data were tabulated and analyzed. The result of this study shows that Vijayakarnataka has 2,255 the highest traffic rank in India Udayavani has 27,903 the highest traffic rank in global. Vijayakarnataka has 7.32 having highest number of average pages viewed per day and 12:40 estimated daily time spent on site by the visitors. Keywords: Webometrics, Newspaper, Newspaper website Evaluation, Kannada Newspaper website, Alexa internet, Alexa databank, Website Analysis. INTRODUCTION News Papers: Information is an important element in every sector of life, be it social, economic, political, educational, industrial and technical development. -

Literature and Culture 739

Literature and Culture 739 CHAPTER XIV LITERATURE AND CULTURE Mandya district is known in the Puranas to have been a part of Dandakaranya forest. It is said there that sages such as Mandavya, Mytreya, Kadamba, Koundliya, Kanva, Agasthya, Gautama and others did penance in this area. Likewise, literature and cultural heritage also come down here since times immemorial. The district of Mandya is dotted with scenic spots like Kunthibetta, Karighatta, Narayanadurga, Gajarajagiri, Adicunchanagiri and other hills; rivers such as Kaveri, Hemavathi, Lokapavani, Shimsha and Viravaishnavi; waterfalls like Gaganachukki, Bharachukki and Shimha; and bird sanctuaries like Ranganathittu, Kokkare Bellur and Gendehosalli, which are sure to have influenced the development of literature and culture of this area. Places like Srirangapattana, Nagamangala, Malavalli, Melukote, Tonnur, Kambadahalli, Bhindiganavile, Govindanahalli, Bellur, Belakavadi, Maddur, Arethippur, Vydyanathapura, Agrahara Bachahalli, Varahnatha Kallahalli, Aghalaya, Hosaholalu, Kikkeri, Basaralu, Dhanaguru, Haravu, Hosabudanuru, Marehalli and others were centers of rich cultural activities in the past. In some places dissemination of knowledge and development of education, arts and spiritual pursuits were carried out by using temples as workshops. Religious places such as Tonnur and Melukote from where Ramanujacharya, who propounded Srivaishanva philosophy; Arethippur, 740 Mandya District Gazetteer Kambadahalli and Basthikote, the centers of Jainism; the temples of Sriranganatha and Gangadharanatha -

Human Rights Violations Against Sexuality Minorities in India

Human rights violations against sexuality minorities in India A PUCL-K fact-finding report about Bangalore - 2 - A Report of PUCL-Karnataka (February 2001) No. of copies: English –– 1000 Kannada –– 500 Available at: • PUCL-K, Bangalore 233 6th Main Road, 4th Block, Jayanagar Bangalore - 560 056 • Sangama, Bangalore Flat 13, III Floor, 'Royal Park' Apartments, (Adjacent to back entrance of Hotel Harsha, Shivajinagar) 34 Park Road, Tasker Town, Bangalore- 560 051 e-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] • Centre for Education and Documentation, Mumbai 3 Suleman Chambers, 4 Battery Street, Mumbai - 400 001 Email: [email protected] • People Tree, Delhi 8 Regal Building, Parliament Street, New Delhi - 110 001 • India Centre for Human Rights and Law, Mumbai 4th Floor, CVOD Jain High School, Hazrat Abbas Street, (84, Samuel Street) Dongri, Mumbai – 400 009 • Counsel Club, Calcutta C/o Ranjan, Post Bag 794, Calcutta - 700 017 Price: INR –– Rs. 25 USD –– $5 GBP –– £3 Human Rights Violations against Sexual Minorities in India PUCL-K, 2001 - 3 - Table of contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... 5 List of terms ................................................................................................................... 6 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Human Rights and Sexuality Minorities ............................................ 7 1.2 Status -

Migrant Labourers, Covid-19 and Working-Class Struggle in the Time of Pandemic: a Report from Karnataka, India Mallige Sirimane and Nisha Thapliyal (11Th June 2020)

Interface: A journal for and about social movements Movement report Volume 12 (1): 164 - 181 (July 2020) Sirimane & Thapliyal, Migrants, Covid-19, Struggle Migrant labourers, Covid-19 and working-class struggle in the time of pandemic: a report from Karnataka, India Mallige Sirimane and Nisha Thapliyal (11th June 2020) Abstract Since the imposition of the unplanned lockdown in India, Karnataka Jan Shakti has worked with stranded migrant labourers to respond to a range of issues including starvation, transportation to return home, sexual violence, Islamophobia and labour rights. Karnataka Jan Shakti (KJS, Karnataka People’s Power) is a coalition of Left-leaning activist groups and individuals. For the last decade, it has mobilised historically oppressed groups on issues of economic and cultural justice including Dalit sanitation workers, Dalit university students, slumdwellers, peasants, nomadic tribes, and survivors of sexual violence. Our approach to collective struggle is shaped by the social analysis tools of Karl Marx, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar and Shankar Guha Niyogi. In this article, we document and analyse our struggle against situated forms of precarity in migrant lives shaped by class, caste, gender, age, and rural/urban geography which have been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic. We also reflect on lessons for movement-building in a political milieu dominated by a hyper surveillant fascist state, communal media apparatus and accelerated, unregulated privatisation under the latest national slogan of Self-Reliant India (AtmaNirbhar Bharat). Keywords: Migrant labourers, Covid-19 pandemic, India, learning in the struggle Introduction On March 24 2020, Prime Minister Narendra Modi (BJP, Bharatiya Janata Party) announced a three-week national lockdown to stop the spread of the coronavirus. -

Press Council of India

PRESS COUNCIL OF INDIA Annual Report (April 1, 2013- March 31, 2014) New Delhi Printed at : Chandu Press, D-97, Shakarpur, Delhi-110092 Press Council of India Soochna Bhawan, 8, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi - 110 003 Chairman: Mr. Justice Markandey Katju Editors of Indian Languages Newspapers (Clause (a) of Sub-Section (3) of Section 5) NAME ORGANISATION NOMINATED BY NEWSPAPERS Shri K. S. Sachidananda Editor’s Guild of India, Malayala Manorama, Murthy All India Newspaper Editors’ Conference and Malayalam Daily, Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Kottayam, Kerala Shri Shravan Kumar Editor’s Guild of India, Nai Duniya, Indore Garg All India Newspaper Editors’ Conference and Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Shri Jagjit Singh Dardi Editor’s Guild of India, Charhdikala, All India Newspaper Editors’ Conference and Punjabi Daily, Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Patiala, Punjab Shri Sheetla Singh Editor’s Guild of India, Janmorcha, All India Newspaper Editors’ Conference and Hindi Daily, Faizabad, Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Uttar Pradesh Shri Anil Jugalkishor Editor’s Guild of India, Daily Amravati Mandal, Agrawal All India Newspaper Editors’ Conference and Amravati, Maharashtra Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Shri Bishambhar Newar All India Newspaper Editors’ Conference and Chhapte-Chhapte, Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Hindi Daily, West Bengal Working Journalists other than Editors (Clause (a) of Sub-Section (3) of Section 5) Shri Rajeev Ranjan National Union of Journalists, Press Association, India News Weekly, Nag Working News Cameramen’s Association and New Delhi Indian Journalists Union Shri Uppala Lakshman National Union of Journalists, Press Association Samayam, and Working News Cameramen’ s Association Telugu Daily, Hyderabad Shri Arvind S. -

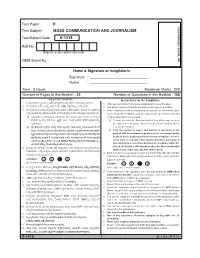

K-1418 (Mass Communication and Journalism) (Paper II).Pdf

Test Paper : II TE Test Subject : MASS COMMUNICATION AND JOURNALISM ST BOO Test Subject Code : K-1418 K L E T Roll No. S E R I (Figures as per admission card) AL N O OMR Sheet No. : ____________________ . Name & Signature of Invigilator/s Signature : _________________________________ Name : _________________________________ Time : 2 Hours Maximum Marks : 200 Number of Pages in this Booklet : 32 Number of Questions in this Booklet : 100 A»Ü¦ìWÜÚWæ ÓÜãaÜ®æWÜÙÜá Instructions for the Candidates 1. D ±Üâo¨Ü ÊæáàÆᤩ¿áÈÉ J¨ÜXst ÓܧÙܨÜÈÉ ¯ÊÜá¾ ÃæãàÇ… ®ÜíŸÃÜ®Üá° ŸÃæÀáÄ. 1. Write your roll number in the space provided on the top of this page. 2. D ±Ü£ÅPæ¿áá ŸÖÜá BÁáR Ë«Ü¨Ü ®ÜãÃÜá (100) ±ÜÅÍæ°WÜÙÜ®Üá° JÙÜWæãíw¨æ. 2. This paper consists of Hundred multiple-choice type of questions. 3. ±ÜÄàPæÒ¿á ±ÝÅÃÜí»Ü¨ÜÈÉ, ±ÜÅÍæ° ±ÜâÔ¤Pæ¿á®Üá° ¯ÊÜáWæ ¯àvÜÇÝWÜáÊÜâ¨Üá. Êæã¨ÜÆ 5 ¯ËáÐÜWÜÙÜÈÉ 3. At the commencement of examination, the question booklet will be given ¯àÊÜâ ±ÜâÔ¤Pæ¿á®Üá° ñæÃæ¿áÆá ÊÜáñÜᤠPæÙÜX®Üíñæ PÜvÝx¿áÊÝX ±ÜÄàQÒÓÜÆá PæãàÃÜÇÝX¨æ. to you. In the first 5 minutes, you are requested to open the booklet and (i) ±ÜÍæ°±ÜâÔ¤PæWæ ±ÜÅÊæàÍÝÊÜPÝÍÜ ±Üvæ¿áÆá, D Öæã©Pæ ±Üâo¨Ü Aíb®Ü ÊæáàÈÃÜáÊÜ compulsorily examine it as below : ±æà±ÜÃ… ÔàÆ®Üá° ÖÜÄÀáÄ. ÔrPÜRÃ… ÔàÇ… CÆÉ¨Ü A¥ÜÊÝ ñæÃæ¨Ü ±ÜâÔ¤Pæ¿á®Üá° (i) To have access to the Question Booklet, tear off the paper seal on ÔÌàPÜÄÓܸæàw. the edge of the cover page. Do not accept a booklet without sticker (ii) ±ÜâÔ¤Pæ¿áÈÉ®Ü ±ÜÅÍæ°WÜÙÜ ÓÜíTæ ÊÜáñÜᤠ±ÜâoWÜÙÜ ÓÜíTæ¿á®Üá° ÊÜááS±Üâo¨Ü ÊæáàÇæ seal or open booklet.