Whiskey in Early America Grace Bellino

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unit 3 the FEDERALIST ERA

Unit 3 THE FEDERALIST ERA CHAPTER 1 THE NEW NATION ..........................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER 2 HAMILTON AND JEFFERSON— THE MEN AND THEIR PHILOSOPHIES .....................6 CHAPTER 3 PAYING THE NATIONAL DEBT ................................................................................................12 CHAPTER 4 ..............................................................................................................................................................16 HAMILTON, JEFFERSON, AND THE FIRST NATIONAL BANK OF THE UNITED STATES.............16 CHAPTER 5 THE WHISKEY REBELLION ........................................................................................................20 CHAPTER 6 NEUTRALITY AND THE JAY TREATY .....................................................................................24 CHAPTER 7 THE SEDITION ACT AND THE VIRGINIA AND KENTUCKY RESOLUTIONS ...........28 CHAPTER 8 THE ELECTION OF 1800................................................................................................................34 CHAPTER 9 JEFFERSONIANS IN OFFICE.......................................................................................................38 by Thomas Ladenburg, copyright, 1974, 1998, 2001, 2007 100 Brantwood Road, Arlington, MA 02476 781-646-4577 [email protected] Page 1 Chapter 1 The New Nation A Search for Answers hile the Founding Fathers at the Constitutional Convention debated what powers should be -

The Presidents of Mount Rushmore

The PReSIDeNTS of MoUNT RUShMoRe A One Act Play By Gloria L. Emmerich CAST: MALE: FEMALE: CODY (student or young adult) TAYLOR (student or young adult) BRYAN (student or young adult) JESSIE (student or young adult) GEORGE WASHINGTON MARTHA JEFFERSON (Thomas’ wife) THOMAS JEFFERSON EDITH ROOSEVELT (Teddy’s wife) ABRAHAM LINCOLN THEODORE “TEDDY” ROOSEVELT PLACE: Mount Rushmore National Memorial Park in Keystone, SD TIME: Modern day Copyright © 2015 by Gloria L. Emmerich Published by Emmerich Publications, Inc., Edenton, NC. No portion of this dramatic work may be reproduced by any means without specific permission in writing from the publisher. ACT I Sc 1: High school students BRYAN, CODY, TAYLOR, and JESSIE have been studying the four presidents of Mount Rushmore in their history class. They decided to take a trip to Keystone, SD to visit the national memorial and see up close the faces of the four most influential presidents in American history. Trying their best to follow the map’s directions, they end up lost…somewhere near the face of Mount Rushmore. All four of them are losing their patience. BRYAN: We passed this same rock a half hour ago! TAYLOR: (Groans.) Remind me again whose idea it was to come here…? CODY: Be quiet, Taylor! You know very well that we ALL agreed to come here this summer. We wanted to learn more about the presidents of Mt. Rushmore. BRYAN: Couldn’t we just Google it…? JESSIE: Knock it off, Bryan. Cody’s right. We all wanted to come here. Reading about a place like this isn’t the same as actually going there. -

Lactic Acid Bacteria – the Uninvited but Generally Welcome Participants In

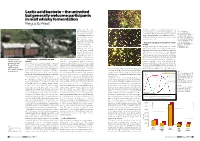

Lactic acid bacteria – the uninvited (a) but generally welcome participants in malt whisky fermentation Fergus G. Priest Coffey still. Like malt diversity resulting in Lactobacillus fermentum and LEFT: (b) whisky, it must be matured Lactobacillus paracasei as commonly dominant species by Fig. 1. Fluorescence photomicrographs of whisky for a minimum of 3 years. about 40 hours. During the final stages when the yeast is fermentation samples; green cells Grain whisky is the base of dying, a homofermentative bacterium related to Lacto- are viable, red cells are dead. (a) the standard blends such as bacillus acidophilus often proliferates and produces large Wort on entering the washback, (b) Famous Grouse, Teachers, amounts of lactic acid. after fermentation for 55 hours and and Johnnie Walker which (c) after fermentation for 95 hours. (a) AND (b) ARE REPRODUCED will contain between 15 Effects of lactobacilli on the flavour of malt WITH PERMISSION FROM VAN BEEK & and 30 % malt whisky. whisky PRIEST (2002, APPL ENVIRON Both products use a The bacteria can affect the flavour of the spirit in two MICROBIOL 68, 297–305); (c) COURTESY F. G. PRIEST similar process, but here ways. First, they will reduce the pH of the fermentation we will focus on malt (c) through the production of acetic and lactic acids. This whisky. Malted barley is will lead to a general increase in esters following milled, infused in water at distillation, a positive feature that has traditionally been about 64 °C for some 30 associated with the late lactic fermentation. This general minutes to 1 hour and the effect is apparent in the data presented in Fig. -

Fires at Valley Forge by Barrett H. Clark

Name Date American History Plays Chapter 7 Fires at Valley Forge by Barrett H. Clark During the winter of 1777–1778, Revolutionary War general George Washington and his army camped at Valley Forge, twenty miles from Philadelphia. In the spring they would resume fighting the British army to win independence for the United States. This play dramatizes a scene that could have happened during that long, difficult winter. CHARACTERS will act out the episode. Imagine on this stage. The Speaker. (Indicating area about him.) . deep snow which O’Malley, a corporal. has drifted here and there. Imagine tall maples Ephraim Coates, a farmer’s son. and firs and beeches here. (Indicates space Joseph Jones, a farmer’s son. behind him.) Over there . (Points Upstage, Left.) William Evans, a bootmaker’s son. just in front of one of those maple trees, a Ben Holden, apprenticed to Benjamin Franklin, man crouches, trying to start a fire under a small the printer. pile of branches. Major Monroe, Aide to Washington. (On cue “maple trees,” the Corporal enters. His coat George Washington, Commander-in-Chief of collar is turned up and he blows on his hands. He the Continental Army. carries an old-fashioned musket, which he lays against a chair.) SCENE. AN OUTPOST IN THE WOODS NEAR VALLEY FORGE. Speaker (smiling pleasantly): That chair suggests a TIME. EARLY EVENING. WINTER, 1777—78. small embankment of snow . (The Corporal blows on his hands.) . a poor attempt to break the force No scenery is used, no costumes and only a few of a biting north wind. -

Massachusetts Historical Society, Adams Papers Editorial Project

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative of a previously funded grant application, which conforms to a past set of grant guidelines. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the application guidelines for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Research Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Adams Papers Editorial Project Institution: Massachusetts Historical Society Project Director: Sara Martin Grant Program: Scholarly Editions and Translations Program Statement of Significance and Impact The Adams Papers Editorial Project is sponsored by and located at the Massachusetts Historical Society (MHS). The Society’s 300,000-page Adams Family Papers manuscript collection, which spans more than a century of American history from the Revolutionary era to the last quarter of the nineteenth century, is consulted during the entire editing process, making the project unique among large-scale documentary editions. The Adams Papers has published 52 volumes to date and will continue to produce one volume per year. Free online access is provided by the MHS and the National Archives. -

Alcohol Units a Brief Guide

Alcohol Units A brief guide 1 2 Alcohol Units – A brief guide Units of alcohol explained As typical glass sizes have grown and For example, most whisky has an ABV of 40%. popular drinks have increased in A 1 litre (1,000ml) bottle of this whisky therefore strength over the years, the old rule contains 400ml of pure alcohol. This is 40 units (as 10ml of pure alcohol = one unit). So, in of thumb that a glass of wine was 100ml of the whisky, there would be 4 units. about 1 unit has become out of date. And hence, a 25ml single measure of whisky Nowadays, a large glass of wine might would contain 1 unit. well contain 3 units or more – about the The maths is straightforward. To calculate units, same amount as a treble vodka. take the quantity in millilitres, multiply it by the ABV (expressed as a percentage) and divide So how do you know how much is in by 1,000. your drink? In the example of a glass of whisky (above) the A UK unit is 10 millilitres (8 grams) of pure calculation would be: alcohol. It’s actually the amount of alcohol that 25ml x 40% = 1 unit. an average healthy adult body can break down 1,000 in about an hour. So, if you drink 10ml of pure alcohol, 60 minutes later there should be virtually Or, for a 250ml glass of wine with ABV 12%, none left in your bloodstream. You could still be the number of units is: suffering some of the effects the alcohol has had 250ml x 12% = 3 units. -

Know Your Liquor VODKA WHISKY

Know Your Liquor VODKA Good to know: Vodka is least likely to give you a hangover Vodka is made by fermenting grains or crops such as potatoes with yeast. It's then purified and repeatedly filtered, often through charcoal, strange as it sounds, until it's as clear as possible. CALORIES: Because vodka contains no carbohydrates or sugars, it contains only calories from ethanol (around 7 calories per gram), making it the least-fattening alcoholic beverage. So a 35ml shot of vodka would contain about 72 calories. PROS: Vodka is the 'cleanest' alcoholic beverage because it contains hardly any 'congeners' - impurities normally formed during fermentation.These play a big part in how bad your hangover is. Despite its high alcohol content - around 40 per cent - vodka is the least likely alcoholic drink to leave you with a hangover, said a study by the British Medical Association CONS: Vodka is often a factor in binge drinking deaths because it is relatively tasteless when mixed with fruit juices or other drinks. HANGOVER SEVERITY: 3/10 WHISKY Good to know: Whisky or Scotch is distilled from fermented grains, such as barley or wheat, then aged in wooded casks. Whisky 'madness': It triggers erratic and unpredictable behaviour because most people drink whisky neat CALORIES: About 80 calories per 35ml shot. PROS: Single malt whiskies have been found to contain high levels of ellagic acid, according to Dr Jim Swan of the Royal Society of Chemists. This powerful acid inhibits the growth of tumours caused by certain carcinogens and kills cancer cells without damaging healthy cells. -

Alcohol and Getting Older: Ageing Well

Reviewing your drinking Ask your pharmacist or doctor whether it’s safe to www.alcoholireland.ie mix your medicine with alcohol. If you are worried about your alcohol use, talk to your GP. S/he will be able to offer you information For general information and advice, and refer you to the support or service on alcohol go to best suited to your needs. Alcohol and Talk to family and friends who you think could be www.alcoholireland.ie of help. Getting Older: It’s never too late to make the changes that will make your life even better. Ageing Well For general information on alcohol go to www.alcoholireland.ie If you are worried about your alcohol use, talk to your GP www.alcoholireland.ie There are many Your health and alcohol How much is too much? benefits Many of us enjoy a drink particularly in a social The guidelines for low-risk drinking are up occasion with friends or family: associated to 14 units a week for a woman (11 standard drinks) and 21 units for a man (17 standard • As we age, however, our ability to break down with reducing drinks), spread out over the week with at alcohol is reduced and we are more susceptible your drinking least 2/3 days alcohol free. These guidelines to the effects of alcohol. As a result, a person apply to healthy adults - if you are ill or on can develop problems with alcohol as they medication, these low-risk guidelines may be grow older, even when drinking habits remain too high. -

THE CORRESPONDENCE of ISAAC CRAIG DURING the WHISKEY REBELLION Edited by Kenneth A

"SUCH DISORDERS CAN ONLY BE CURED BY COPIOUS BLEEDINGS": THE CORRESPONDENCE OF ISAAC CRAIG DURING THE WHISKEY REBELLION Edited by Kenneth A. White of the surprisingly underutilized sources on the early history Oneof Pittsburgh is the Craig Papers. Acase inpoint is Isaac Craig's correspondence during the Whiskey Rebellion. Although some of his letters from that period have been published, 1 most have not. This omission is particularly curious, because only a few eyewitness ac- counts of the insurrection exist and most ofthose were written from an Antifederalist viewpoint. These letters have a value beyond the narration of events, how- ever. One of the questions debated by historians is why the federal government resorted to force to put down the insurrection. Many have blamed Alexander Hamilton for the action, attributing it to his per- sonal approach to problems or to his desire to strengthen the central government. 2 These critics tend to overlook one fact : government officials make decisions based not only on their personal philosophy but also on the facts available to them. As a federal officer on the scene, Craig provided Washington and his cabinet with their informa- Kenneth White received his B.A. and M.A.degrees from Duquesne Uni- versity. While working on his master's degree he completed internships with the Adams Papers and the Institute of Early American History and Culture. Mr. White is presently working as a fieldarchivist for the Pennsylvania His- torical and Museum Commission's County Records Survey and Planning Study.— Editor 1 Portions of this correspondence have been published. For example, all or parts of six of these letters appeared in Harold C. -

Beer & Cider Wine C Ockt Ails Gin Goblet S Jugs

COCKTAILS GIN GOBLETS JUGS JUGS GIN GOBLETS COCKTAILS BEER & CIDER POT PINT WINE 125ml Bott ON TAP COCKTAILS 285ML 570ML CHAMPAGNE & SPARKLING — — CLASSICS AVAILABLE PLEASE ASK ROTHBURY ESTATE SPARKLING NV HUNTER VALLEY NSW 10 45 FURPHY REFRESHING ALE 6.5 12 STRAWBERRY SWING 21 AZAHARA MOSCATO NV RED CLIFFS VIC 10 45 FURPHY CRISP LAGER 6.5 12 BOMBAY SAPPHIRE, PAMA LIQUEUR, LEMON, STRAWBERRIES, SUGAR T’GALLANT PROSECCO NV YARRA VALLEY VIC 12 58 CARLTON DRAUGHT 7 13 CHANDON BRUT NV YARRA VALLEY VIC 14 82 WATERMELON SUGAR 20 BALTER XPA 7.5 14 EL JIMADOR, WATERMELON, LIME, SUGAR & SALT RIM CHANDON BRUT ROSÉ NV YARRA VALLEY VIC 14 82 JANSZ BRUT ROSÉ MAGNUM NV TASMANIA 140 LITTLE CREATURES PALE ALE 7.5 14 AMALFI SOUR 21 42 BELOW, BASS & FLINDERS LIMONCELLO, VEUVE CLICQUOT BRUT NV CHAMPAGNE FRANCE 135 PANHEAD SUPERCHARGER IPA 7.5 14 LEMON, SUGAR, EGG WHITE ASAHI SUPER DRY 400ML 13 NANA’S NIGHTCAP 21 ROSÉ & DESSERT 150ml 250ml Bott APPLE PIE MOONSHINE, BACARDI SPICED, APPLE PUREE, WHITE RABBIT DARK ALE 7.5 14 2020 SQUEALING PIG ROSÉ MARLBOROUGH NZ 11 17 52 LEMON, EGG WHITE PIPSQUEAK APPLE CIDER 7 13 2019 DOMAINE DE TRIENNES ROSÉ PROVENCE FRANCE 12 20 60 SPLICE UP YOUR LIFE 20 BREWMANITY TANGO & SPLASH JUICY LAGER 6.5 12 42 BELOW, MIDORI, PEACH SYRUP, PINEAPPLE, LIME 2019 LA LA LAND ROSÉ VIC 43 BIG FREEZE FIGHT MND BEER COFFEE NEGRONI 22 2017 CAPE MENTELLE ROSÉ MARGARET RIVER WA 62 FOUR PILLARS RARE DRY, CAMPARI, SWEET VERMOUTH, 2019 ROGERS & RUFUS ROSÉ MAGNUM 110 COLD BREW COFFEE ASK ABOUT OUR RANGE OF BOTTLES/CANS BAROSSA VALLEY SA MOCKTAIL -

2019 Scotch Whisky

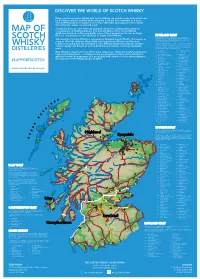

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

Neurochemical Mechanisms Underlying Alcohol Withdrawal

Neurochemical Mechanisms Underlying Alcohol Withdrawal John Littleton, MD, Ph.D. More than 50 years ago, C.K. Himmelsbach first suggested that physiological mechanisms responsible for maintaining a stable state of equilibrium (i.e., homeostasis) in the patient’s body and brain are responsible for drug tolerance and the drug withdrawal syndrome. In the latter case, he suggested that the absence of the drug leaves these same homeostatic mechanisms exposed, leading to the withdrawal syndrome. This theory provides the framework for a majority of neurochemical investigations of the adaptations that occur in alcohol dependence and how these adaptations may precipitate withdrawal. This article examines the Himmelsbach theory and its application to alcohol withdrawal; reviews the animal models being used to study withdrawal; and looks at the postulated neuroadaptations in three systems—the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmitter system, the glutamate neurotransmitter system, and the calcium channel system that regulates various processes inside neurons. The role of these neuroadaptations in withdrawal and the clinical implications of this research also are considered. KEY WORDS: AOD withdrawal syndrome; neurochemistry; biochemical mechanism; AOD tolerance; brain; homeostasis; biological AOD dependence; biological AOD use; disorder theory; biological adaptation; animal model; GABA receptors; glutamate receptors; calcium channel; proteins; detoxification; brain damage; disease severity; AODD (alcohol and other drug dependence) relapse; literature review uring the past 25 years research- science models used to study with- of the reasons why advances in basic ers have made rapid progress drawal neurochemistry as well as a research have not yet been translated Din understanding the chemi- reluctance on the part of clinicians to into therapeutic gains and suggests cal activities that occur in the nervous consider new treatments.