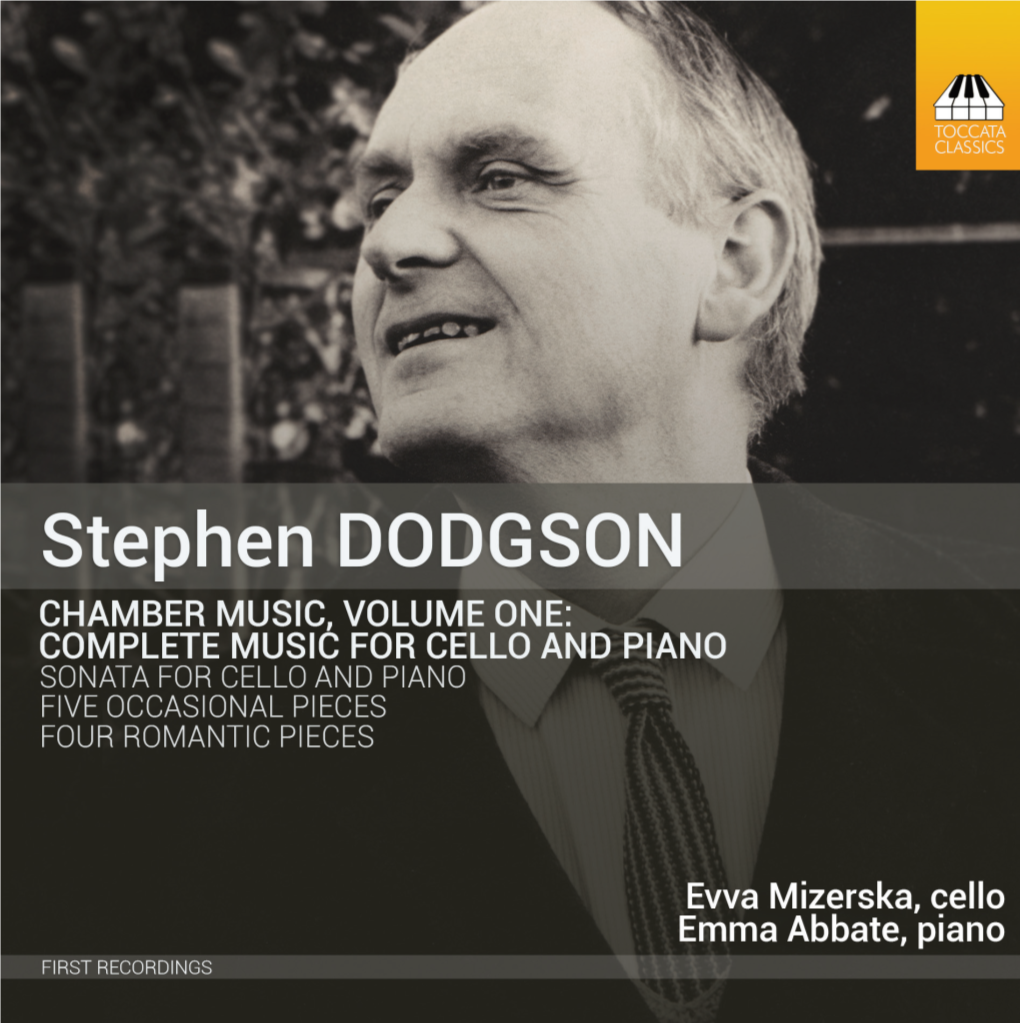

TOC 0353 CD Booklet.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Duality of the Composer-Performer

The Duality of the Composer-Performer by Marek Pasieczny Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Arts Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Supervisors: Prof. Stephen Goss ©Marek Pasieczny 2015 The duality of the composer-performer A portfolio of original compositions, with a supplementary dissertation ‘Interviews Project: Thirteen Composers on Writing for the Guitar’. Abstract The main focus of this submission is the composition portfolio which consists of four pieces, each composed several times over for different combinations of instruments. The purpose of this PhD composition portfolio is threefold. Firstly, it is to contribute to the expansion of the classical guitar repertoire. Secondly, it is to defy the limits imposed by the technical facilities of the physical instrument and bring novelty to its playability. Third and most importantly, it is to overcome the challenges of being a guitarist-composer. Due to a high degree of familiarity with the traditional guitar repertoire, and possessing intimate knowledge of the instrument, it is often difficult for me as a guitarist-composer to depart from habitual tendencies to compose truly innovative works for the instrument. I have thus created a compositional approach whereby I separated my role as a composer from my role as a guitarist in an attempt to overcome this challenge. I called it the ‘dual-role’ approach, comprising four key strategies that I devised which involves (1) borrowing ‘New Music’ practices to defy traditionalist guitar tendencies which are often conservative and insular; (2) adapting compositional materials to different instrumentations; and expanding on (3) the guitar technique as well as; (4) the guitar’s inventory of extended techniques. -

Margaret Catchpole: Two Worlds Apart

Stephen DODGSON Margaret Catchpole: Two Worlds Apart (Chamber opera in four acts) Howden • Wallace • Morris • Ollerenshaw Edgar-Wilson • Brook • Moore • Willcock • Sporsén Perpetuo • Julian Perkins Stephen Act I: By the Banks of the Orwell Act II: The Cobbold Household 1 [Introduction] 2:27 Scene 1: The drawing room at Mrs Cobbold’s house DO(1D924G–20S13O) N ^ 2Scene 1: Harvest time at Priory Farm & You are young (Dr Stebbing) 4:25 3 What an almighty fuss (Luff, Laud) 1:35 Ah! Dr Stebbing and Mr Barry Margaret Catchpole: Two Worlds Apart 4 For so many years (Laud, Luff) 2:09 (Mrs Cobbold, Barry, Margaret) 6:54 Chamber opera in four acts (1979) 5 Oh harvest moon (Margaret, Laud) 5:26 * Under that far and shining sky Interlude to Scene 2 1:28 Libretto by Ronald Fletcher (1921–1992), 6 (Laud, Margaret) 1:35 based on the novel by Richard Cobbold (1797–1877) The harvest is ended Scene 2: Porch – Kitchen/parlour – First performance: 8–10 June 1979 at The Old School, Hadleigh, Suffolk, UK 7 (Denton, Margaret, Laud, Labourers) 2:19 (Drawing room Oh, my goodness gracious – look! I don’t care what you think Margaret Catchpole . Kate Howden, Mezzo-soprano 8 (Mrs Denton, Lucy, Margaret, Denton) 2:23 ) (Alice, Margaret) 2:26 Will Laud . William Wallace, Tenor 9 Margaret? (Barry, Margaret) 3:39 Come in, Margaret John Luff . Nicholas Morris, Bass The ripen’d corn in sheaves is born ¡ (Mrs Cobbold, Margaret) 6:30 (Second Labourer, Denton, First Labourer, John Barry . Alistair Ollerenshaw, Baritone Come then, Alice (Margaret, Alice, Laud) 8:46 0 Mrs Denton, Lucy, Barry) 5:10 ™ Crusoe . -

'Colloquy' CD Booklet.Indd

Colloquy WORKS FOR GUITAR DUO BY PURCELL · PHILIPS · JOHNSON · VAUGHAN WILLIAMS DODGSON · PHIBBS · DOWLAND · MAXWELL DAVIES DUO GUITARTES RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS (1872–1958) COLLOQUY 10. Fantasia on Greensleeves [5.54] JOSEPH PHIBBS (b.1974) Serenade HENRY PURCELL (1659–1695) 11. I. Dialogue [3.54] Suite, Z.661 (arr. Duo Guitartes) 12. II. Corrente [1.03] 1. I. Prelude [1.18] 13. III. Liberamente [2.48] 2. II. Almand [4.14] WORLD PREMIÈRE RECORDING 3. III. Corant [1.30] 4. IV. Saraband [2.47] PETER MAXWELL DAVIES (1934–2016) Three Sanday Places (2009) PETER PHILIPS (c.1561–1628) 14. I. Knowes o’ Yarrow [3.03] 5. Pauana dolorosa Tregian (arr. Duo Guitartes) [6.04] 15. II. Waters of Woo [1.49] JOHN DOWLAND (1563–1626) 16. III. Kettletoft Pier [2.23] 6. Lachrimae antiquae (arr. Duo Guitartes) [1.56] STEPHEN DODGSON (1924–2013) 7. Lachrimae antiquae novae (arr. Duo Guitartes) [1.50] 17. Promenade I [10.04] JOHN JOHNSON (c.1540–1594) TOTAL TIME: [57.15] 8. The Flatt Pavin (arr. Duo Guitartes) [2.08] 9. Variations on Greensleeves (arr. Duo Guitartes) [4.22] DUO GUITARTES STEPHEN DODGSON (1924–2013) Dodgson studied horn and, more importantly to him, composition at the Royal College of Music under Patrick Hadley, R.O. Morris and Anthony Hopkins. He then began teaching music in schools and colleges until 1956 when he returned to the Royal College to teach theory and composition. He was rewarded by the institution in 1981 when he was made a fellow of the College. In the 1950s his music was performed by, amongst others, Evelyn Barbirolli, Neville Marriner, the Philip Jones Brass Ensemble and the composer Gerald Finzi. -

Radiotimes-July1967.Pdf

msmm THE POST Up-to-the-Minute Comment IT is good to know that Twenty. Four Hours is to have regular viewing time. We shall know when to brew the coffee and to settle down, as with Panorama, to up-to- the-minute comment on current affairs. Both programmes do a magnifi- cent job of work, whisking us to all parts of the world and bringing to the studio, at what often seems like a moment's notice, speakers of all shades of opinion to be inter- viewed without fear or favour. A Memorable Occasion One admires the grasp which MANYthanks for the excellent and members of the team have of their timely relay of Die Frau ohne subjects, sombre or gay, and the Schatten from Covent Garden, and impartial, objective, and determined how strange it seems that this examination of controversial, and opera, which surely contains often delicate, matters: with always Strauss's s most glorious music. a glint of humour in the right should be performed there for the place, as with Cliff Michelmore's first time. urbane and pithy postscripts. Also, the clear synopsis by Alan A word of appreciation, too, for Jefferson helped to illuminate the the reporters who do uncomfort- beauty of the story and therefore able things in uncomfortable places the great beauty of the music. in the best tradition of news ser- An occasion to remember for a Whitstabl*. � vice.-J. Wesley Clark, long time. Clive Anderson, Aughton Park. Another Pet Hate Indian Music REFERRING to correspondence on THE Third Programme recital by the irritating bits of business in TV Subbulakshmi prompts me to write, plays, my pet hate is those typists with thanks, and congratulate the in offices and at home who never BBC on its superb broadcasts of use a backing sheet or take a car- Indian music, which I have been bon copy. -

Blanche Mcintyre Director / Writer

Blanche McIntyre Director / Writer * Winner - Best Director: TMA 2013 UK Theatre Awards * Winner of the 2011 Critcs' Circle Most Promising Newcomer Award for ACCOLADE and FOXFINDER (both at the Finborough Theatre) * FOXFINDER: Listed in Independent's top 5 picks for 2011 * ACCOLADE: Best Director and Best Production at Off West End Theatre Awards 2011; Listed in the Spectator's Top Ten Plays for 2011; Time Out's Best Fringe Show 2011 National Theatre Studio Director's Course (2010) Winner - Leverhulme Bursary (2009) Agents Giles Smart Assistant Ellie Byrne [email protected] +44 (020 3214 0812 Credits In Development Production Company Notes THE LITTLE FOXES Gate Theatre, Dublin By Lillian Hellman 2020 Theatre Production Company Notes HYMN Almeida / Sky Arts By Lolita Chakrabarti 2021 United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes BOTTICELLI IN THE FIRE Hampstead By Jordan Tannahill 2019 BARTHOLOMEW FAIR Shakespeare's Globe - By Ben Jonson 2019 Sam Wanamaker Playhouse TARTUFFE National Theatre By Molière 2019 Adapted by John Donnelly & Director Blanche McIntyre WOMEN IN POWER Nuffield Based on Aristophanes' 2018 ASSEMBLY WOMEN THE WINTER'S TALE Shakespeare's Globe By William Shakespeare 2018 THE WRITER Almeida By Ella Hickson 2018 TITUS ANDRONICUS RSC By William Shakespeare 2017 THE NORMAN CONQUESTS Chichester Festival By Alan Ayckbourn 2017 Theatre THE TWO NOBLE KINSMEN RSC: The Swan By William Shakespeare 2016 NOISES -

Tenth Anniversary Issue Celebrating the Founding of the BHS

ISSUE No. 7. Published by The British Harpsichord Society SUMMER 2013 Tenth Anniversary Issue celebrating the founding of the BHS INTRODUCTIONS Our Guest Editor JANE CHAPMAN and our Founder WILLIAM VINE p1 NEWS ICHKM The 2nd International Conference in Edinburgh, Dartington p6 International Summer School, The BHS Composition Competition Prize Winners Concert, & ‘Roots of Revival’ Horniman Museum Conference. FEATURES The 10th Anniversary Composition Competition‐ PAMELA NASH p9 The Harpsichord music of Sister Caecile‐ ANDREW WOOLLEY p15 Painting Music‐ CATHERINE PECK p17 An Introduction to the ‘Oriental Miscellany’‐ JANE CHAPMAN p25 Lateral thinking for Harpsichordists- JANE CLARK p32 The Museum of Instruments at the RCM- JENNY NEX p37 Learning the harpsichord in France, part 2- HÉLÈNE DIOT p50 Michael Thomas & the Bate Collection- DAVID MILLARD p55 REPORT A BHS visit to Cambridge- NICHOLAS NEWTON p13 REVIEWS Sound and Visionary- Louis Bertrand Castel.- DEREK CONNON p34 Celebrating the 85th birthday of Zuzana Růžičková- PAMELA NASH p47 YOUR LETTERS Anthony Fox, Colin Booth p63 OBITUARIES MARY MOBBS, STEPHEN DODGSON and RAFAEL PUYANA p65 Please send your comments & your contributions to [email protected] 1 INTRODUCTION Greetings! This issue marks the 10th anniversary of the British Harpsichord Society, so has something of a celebratory feel. Regular readers already know the score – but for those new to us, the magazine has for each issue a different Guest Editor who selects, searches out and often writes the main features. This time around it has been a pleasure to have harpsichordist Jane Chapman, who has done more to raise the profile of the contemporary instrument than anyone else in the UK; indeed The Independent dubs her ‘the hippest harpsichordist in the UK’. -

TOCC0444DIGIBKLT.Pdf

STEPHEN DODGSON Chamber Music, Volume Three: Music for Oboe Sonata for Oboe and Piano (1987) 15:01 1 I Intrada 1:36 2 II Recitativo e Valse 2:26 3 III Capriccioso 1:58 4 V Grave 2:51 TT 73:43 5 V Moto perpetuo 2:17 6 VI Aria e Ciacona 3:53 Countdown: Suite for Oboe and Harp (1990) 13:49 7 I Salute for a Royal Birthday (Counting candles) 3:38 8 II Nocturne (Counting sheep) 3:11 9 III Burlesque (Counting money) 3:26 10 IV Envoi (Counting your blessings) 3:34 Sonata for Cor Anglais and Piano (1967) 14:45 11 I Andante con moto 4:33 12 II Vivace 2:44 13 III Poco adagio 4:00 14 IV Allegro non tanto 3:28 Three Winter Songs for Soprano with Oboe and Piano (1972) 15:27 15 No. 1 Birds in Winter 5:00 16 No. 2 Winter the Huntsman 5:52 17 No. 3 February 4:35 2 Suite in C minor for oboe and piano (1957) 14:41 18 I Prelude 2:28 19 II Arabesque 2:33 20 III Scherzino 2:27 21 IV Romance 4:06 22 V Finale 3:07 James Turnbull, oboe TT 73:43 Libby Burgess, piano 1 – 6 11 –22 FIRST RecoRdInGS Eleanor Turner, harp 7 – 10 Robyn Allegra Parton, soprano 15 – 17 3 STEPHEN DODGSON – CHAMBER MUSIC, VOLUME THREE: MUSIC FOR OBOE by Lewis Foreman Stephen Dodgson came from an artistic family: the son of the painter and art-teacher John Dodgson (1890–1969), he was born in Chelsea on 17 March 1924. -

University of Southampton Research Repository

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Department of Music Volume 1 of 1 The Harpsichord in Twentieth-Century Britain by Christopher David Lewis Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2017 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Music Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy THE HARPSICHORD IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY BRITAIN by CHRISTOPHER DAVID LEWIS This dissertation provides an overview of the history of the harpsichord in twentieth- century Britain. It takes as its starting point the history of the revival harpsichord in the early part of the century, how the instrument affected both performance of historic music and the composition of modern music and the factors that contributed to its decline. -

The Guitarist and the Non-Guitarist Composer

The Guitarist and the Non-Guitarist Composer: an analysis of contrasting collaborative models and their impact on new works for solo classical guitar Benjamin Peter Ellerby BMus (Honours Class I) A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2020 School of Music Abstract Composer-performer collaboration in the creation of new works for solo classical guitar is shaped by several distinctive challenges, specifically related to notation and technical guitar idioms that often do not make up a part of a composer’s training or experience. In practice, these challenges have typically been overcome through the collaboration of guitarists and non-guitarist composers—leading to the creation of some of the instrument’s most beloved repertoire. While the benefits of compositional collaboration between performers and composers generally are widely documented, questions have been raised regarding the potential for guitarists to inhibit the creative process of non-guitarist composers in collaborative situations involving new works for solo classical guitar. This exegesis explores the issue via two intrinsic case studies, documenting the potential advantages and disadvantages of contrasting collaborative models with a focus on two key components: the composer’s understanding of how to write for the guitar, and the performer’s influence on the composition. Each case study explores the collaboration between a non-guitarist composer and myself as the performer from the earliest stages of a new composition through to its premiere. Aligning with a practice-led research paradigm, my role as both researcher and participant in the project shapes the narrative of the analysis. -

TOCC0453DIGIBKLT.Pdf

STEPHEN DODGSON: CHAMBER MUSIC, VOLUME FOUR MUSIC FOR WINDS I by Lewis Foreman Stephen Dodgson was born in Chelsea on 17 March 1924, into a middle-class artistic family: his father was the painter and art-teacher John Dodgson (1890–1969). Stephen received a public-school education at Berkhampsted School and Stowe. He left school in the middle of the Second World War, and found himself conscripted. Soon he was in the Royal Navy, serving as a sub-lieutenant on the frigate HMS Bentley on Atlantic patrols. Once demobbed, he studied composition with Bernard Stevens, while earning a living with temporary teaching posts. In April 1947 he became a student at the Royal College of Music. The horn was Dodgson’s first study, with the well-known orchestral player Frank Probyn. But Dodgson’s main interest was composition, which he studied with R. O. Morris and Patrick Hadley. He won a Cobbett prize for a Fantasy String Quartet while still a student and, thanks to an Octavia Travelling Fellowship, was able to go to Italy after he left the RCM in July 1949. In Venice he shared a flat with Luigi Nono, then at the start of a very different composing career. Dodgson composed music in most of the traditional forms, and although his huge output for guitar has tended to pigeon-hole him in that specialism, he wrote extensively for many other instruments, not least his own, the French horn. He had a typical portfolio musical career: very much a Royal College of Music man, he taught at the RCM, beginning in the Junior Department before becoming professor of composition and theory in 1965, a position he held for seventeen years; he was made a Fellow of the RCM in 1981. -

Complete Index,1973-2019 Harpsichord & Fortepiano

Harpsichord & fortepiano Complete Index,1973-2019 Harpsichord & fortepiano Harpsichord COMPLETE INDEX, 1973-2019 & fortepiano Harpsichord & fortepiano was Compiled by Francis Knights founded in 1973 by Edgar Hunt as The English Harpsichord Magazine , adopting the current title in 1987. It is published 1 Main Index, 1973-2019 twice a year, in the Spring and Autumn, and is available 26 Subject Index worldwide 26 Instruments Editor Francis Knights, 29 Keyboards and Makers Fitzwilliam College, 32 Stringing, Tuning and Maintenance Cambridge, email 35 Repertoire [email protected] 38 Performance and Teaching Publisher, 41 Collections and Organizations Advertising and Subscriptions 42 Interviews and Profiles Peacock Press Ltd, 45 Obituaries Scout Bottom Farm, Mytholmroyd, 46 Miscellaneous Hebden Bridge, Yorkshire HX7 5JX, United Kingdom, tel 01422 882751 48 Author Index Website www.hfmagazine.info See the website to view the archive, style guide, ad rates and to renew subscriptions Design and Artwork D&P Design and Print Cover photo: Spinet by Edward Blunt (1704), by kind permission of David Hackett ISSN: 1463-0036 (photo: David Hackett) MAIN INDEX, 1973-2019 This chronological Index covers every issue of the English Harpsichord Magazine and Harpsichord & fortepiano , vols.i-xxiii, and includes all of the content apart from names of works reviewed and advertisements. For a Subject Index, including Interviews and Obituaries, see p.26, and for an Author Index of articles, see p.48. The Harpsichord Magazine , i/1 (October 1973) ‘Editorial’, Edgar Hunt, p.1 ‘George Malcolm, C.B.E.: An Interview’, Edgar Hunt, pp.2-5 ‘A Visit to Robert Goble’, [Edgar Hunt], p.6 ‘Early English Harpsichord Building: A Reassessment’, Thomas McGeary, pp.7-19, 30 ‘The Broadwood Books: I’, Charles Mould, pp.19-23 ‘Harpsichord Building: I. -

Burton at the BBC: Classic Excerpts from the BBC Archive Free Ebook

FREEBURTON AT THE BBC: CLASSIC EXCERPTS FROM THE BBC ARCHIVE EBOOK Richard Burton | 1 pages | 19 Nov 2015 | BBC Audio, A Division Of Random House | 9781785292040 | English | London, United Kingdom Julian Bream BBC Radio 3 - - As Radio 4 's Desert Island Discs enters its 70th year, our Scraperwiki spreadsheet reveals a number of themes running through castaways' choices over the past seven decades. With the entire Desert Island Discs archive now available on the BBC Radio 4 websiteguests' selections of books and luxuries are comprehensively revealed in all their profound, surprising - and occasionally downright odd - glory. Since the programme began ina total of 43 guests, including Terry Wogan and George Clooney, elected to while away the hours with Tolstoy's War and Peace, according to the BBC archive. Camila Batmanghelidjh and Raymond Tallis chose the existentialist writings of Sartre and Heidegger to aid the solitude, but Proust was the philosopher of choice, featuring in at least 50 episodes. Unsurprisingly, booze featured heavily on the imaginary island, with politicians particularly Burton at the BBC: Classic Excerpts from the BBC Archive on a tipple. David Cameron was one of dozens of guests who wanted whisky, while David Davis requested "a magic wine cellar which never runs out". Lord Brian Rix's choice of a "proper orthopaedic cushion" epitomised the trend towards home comforts: Christabel Bielenberg chose a Burton at the BBC: Classic Excerpts from the BBC Archive chair"; Daniel Baremboin a piano with a mattress. The musical instrument was a winner, with guests, including Sir Ian McKellen, opting for a piano - perhaps unsurprisingly given of the show's guests have been from stage, screen and radio, and from music backgrounds.