Revitalizing Education in Afghanistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invest in Afghan Women: a Report on Education in Afghanistan a Checkered History

INVEST IN AFGHAN WOMEN: — A REPORT ON — EDUCATION IN AFGHANISTAN Presented by the George W. Bush Institute’s Women’s Initiative OCTOBER 2O13 “I HOPE AMERICANS WILL JOIN OUR FAMILY IN WORKING TO INVEST IN AFGHAN GIRLS ENSURE THAT DIGNITY AND OPPORTUNITY WILL BE SECURED FOR ALL THE WOMEN AND CHILDREN OF AFGHANISTAN.” In October 2012, a Taliban operative shot 15-year-old Pakistani student Malala Yousafzai in the face and neck while she traveled — MRS. LAURA BUSH home on a school bus. The assassination attempt was punishment for her “crime” of advocating for girls’ education. After surgeons repaired her shattered skull, Malala made a full recovery. And on July 12, 2013, she gave a rousing speech at the United Nations, becoming a global voice for girls’ access to education. Malala’s story is inspiring, but unfortunately the evils she’s combating are all too common in her region of the world. Just next door, in Afghanistan, religious fanaticism and deeply entrenched cultural practices have led to the systematic oppression of women and young girls. The Afghan situation is particularly desperate. While her peers in the United States prepare for their freshman year of high school, a typical 14-year-old Afghan girl has already been forced to leave formal education and is at acute risk of mandated marriage and early motherhood. If she beats the odds and attends school, she has reason to fear an attack on her schoolhouse with grenades or poison. A full 76 percent of her countrywomen have never attended school. And only 12.6 percent can read. -

Kabul University Books Corps of Engineers Provides War-Torn University with Engineering Books

March/April 2011 Contractor awards Corps of Engineers recognizes top construction firms. Lisner’s mission N.D. Air Force man serves Army leadership role in Afghanistan. Commander's blog Magness touts role of civilian engineers to bloggers. Intern graduation U.S. Army Corps of Engineers trains and mentors Afghan soldiers. Playing cards Corps of Engineers, Embassy team up to explain the deal with Afghan artifacts. Kabul University books Corps of Engineers provides war-torn university with engineering books. C h Tajikistan in Uz a bekis tan District Commander Col. Thomas Magness AED-North District Command Sergeant Major hshan dak Chief Master Sgt. Forest Lisner Ba Chief of Public Affairs ar J. D. Hardesty uz kh Kund Ta K Layout & Design ash Joseph A. Marek m jan Balkh wz ir Staff Writer Ja Paul Giblin lan Staff Writer gh LaDonna Davis n Ba n ta angan r ta is am e ris n S jsh u e Pan N ar m ul un The Freedom Builder is the field magazine of the Far P K k yab ri n Kapisa n Afghanistan Engineer District, U.S. Army Corps of r a wa L a S ar aghm Engineers; and is an unofficial publication authorized u Bamyan P Kabul by AR 360-1. It is produced monthly for electronic ul ories - r distribution by the Public Affairs Office, U.S. Army T ab St rha K ga Corps of Engineers, Afghanistan Engineer District. It is an produced in the Afghanistan theater of operations. N Views and opinions expressed in The Freedom ardak r Builder are not necessarily those of the Department of n W a dghis g the Army or the U.S. -

ARTICLE Development of a Gold-Standard Pashto Dataset and a Segmentation App Yan Han and Marek Rychlik

ARTICLE Development of a Gold-standard Pashto Dataset and a Segmentation App Yan Han and Marek Rychlik ABSTRACT The article aims to introduce a gold-standard Pashto dataset and a segmentation app. The Pashto dataset consists of 300 line images and corresponding Pashto text from three selected books. A line image is simply an image consisting of one text line from a scanned page. To our knowledge, this is one of the first open access datasets which directly maps line images to their corresponding text in the Pashto language. We also introduce the development of a segmentation app using textbox expanding algorithms, a different approach to OCR segmentation. The authors discuss the steps to build a Pashto dataset and develop our unique approach to segmentation. The article starts with the nature of the Pashto alphabet and its unique diacritics which require special considerations for segmentation. Needs for datasets and a few available Pashto datasets are reviewed. Criteria of selection of data sources are discussed and three books were selected by our language specialist from the Afghan Digital Repository. The authors review previous segmentation methods and introduce a new approach to segmentation for Pashto content. The segmentation app and results are discussed to show readers how to adjust variables for different books. Our unique segmentation approach uses an expanding textbox method which performs very well given the nature of the Pashto scripts. The app can also be used for Persian and other languages using the Arabic writing system. The dataset can be used for OCR training, OCR testing, and machine learning applications related to content in Pashto. -

Promoting Female Enrollment in Public Universities of Afghanistan

Promoting Female Enrollment in Public Universities of Afghanistan Higher Education Development Program Ministry of Higher Education Contents 1. Theme 1.1 Increasing Access to priority Degree Programs (Promoting Female Enrollment) .......... 3 2- Kankor Seat Reservation (Special Seats for Female in Priority Desciplines) ..................................... 3 3- Trasnprtaion Services for Female Students ...................................................................................... 4 4- Day Care Services for Female in Public Universities ........................................................................ 5 - KMU………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 - Bamyan…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 - Takhar…………………………………………………………………………………..………………………………………………….5 - Al-Bironi……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………6 - Parwan……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…….6 5- Counselling Services in Public Univeristies ...................................................................................... 6 - Kabul University - Kabul Education University - Jawzjan University - Bamyan University - Balkh University - Herat University 6- Scholarship (Stipened) for Disadvantaged Female Students ............................................................ 8 7- Female Dorms .................................................................................................................................. 9 2 Theme 1.1: Increasing Access to Priority Degree Programs for Economic Development The objective -

Afghanistan Country Fact Sheet 2018

Country Fact Sheet Afghanistan 2018 Credit: IOM/Matthew Graydon 2014 Disclaimer IOM has carried out the gathering of information with great care. IOM provides information at its best knowledge and in all conscience. Nevertheless, IOM cannot assume to be held accountable for the correctness of the information provided. Furthermore, IOM shall not be liable for any conclusions made or any results, which are drawn from the information provided by IOM. I. CHECKLIST FOR VOLUNTARY RETURN 1. Before the return 2. After the return II. HEALTH CARE 1. General information 2. Medical treatment and medication III. LABOUR MARKET AND EMPLOYMENT 1. General information 2. Ways/assistance to find employment 3. Unemployment assistance 4. Further education and trainings IV. HOUSING 1. General Information 2. Ways/assistance to find accommodation 3. Social grants for housing V. SOCIAL WELFARE 1. General Information 2. Pension system 3. Vulnerable groups VI. EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM 1. General Information 2. Cost, loans and stipends 3. Approval and verification of foreign diplomas VII. CONCRETE SUPPORT FOR RETURNEES 1. Reintegration assistance programs 2. Financial and administrative support 3. Support to start income generating activities VIII. CONTACT INFORMATION AND USEFUL LINKS 1. International, Non-Governmental, Humanitarian Organizations 2. Relevant local authorities 3. Services assisting with the search for jobs, housing, etc. 4. Medical Facilities 5. Other Contacts For further information please visit the information portal on voluntary return and reintegration ReturningfromGermany: 2 https://www.returningfromgermany.de/en/countries/afghanistan I. Checklist for Voluntary Return Insert Photo here Credit: IOM/ 2003 Before the Return After the Return The returnee should The returnee should ✔request documents: e.g. -

INSPIRE the Monthly Employee Newsletter

19th Issue INSPIRE The Monthly Employee Newsletter November 2020 Employee of The Month Ms. Sajida Mohammad Tayyeb Economics Department Lecturer Staff Birthdays New Employees Introduction Reflections Birthday Wishes Kardan University wishes a happy birthday to all of our employees who celebrate their birthdays in November. Wahidullah Ibrahimkhail Ahmad Zaki Ludin November 2 November 4 Sarbajeet Mukherjee Faisal Hashimi November 6 November 6 Alauddin Qurishi Jahanzeb Ahmadzai November 8 November 11 Ahmad Khetab Roohullah Hassanyar November 22 November 13 Employee of the Month Ms. Sajida Mohammad Tayyeb Economics Department Lecturer We are pleased to announce Ms. Sajida Mohammad Tayyeb as our Employee for November 2020. Ms. Tayyeb is an inspiring, committed, and dedicated employee of Kardan University. Ms. Sajida has been immensely cooperative with her students, who are on the verge of graduation to complete their final project. She is handling the online sessions of the department with diligence. Additionally, she has been deeply involved in developing the Departments and the Faculty of Economics' Strategic Plan for the past month. She is also working with the DRD to conduct the upcoming National Conference on SDGs. She is a very dedicated employee, kind teacher, and energetic colleague. The whole department is happy to work by her side We congratulate her on this achievement and wish her the best of luck in her future endeavors. New Employees Introduction Mr. Abdullah Salihy Graphic Designer Mr. Abdullah Salihy joined Kardan University as a Graphic Designer in the Office of Communications. Mr. Salihy holds a bachelor's degree in Fine Arts with a specialization in Graphic Design from Kabul University. -

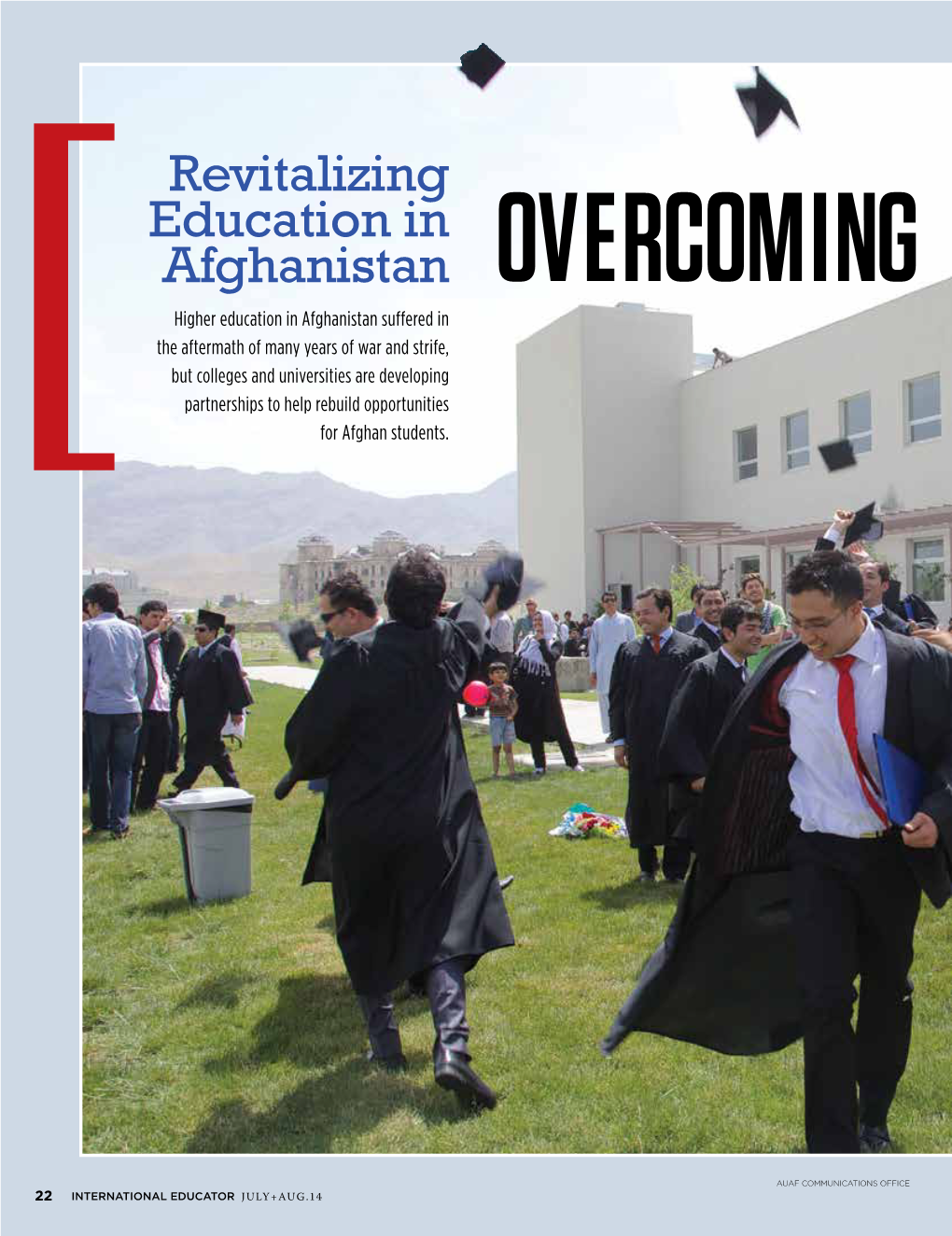

Can Afghan Universities Recover from War

NEWSFOCUS Afghan elite. Graduates at Ameri- can University of Afghanistan in Kabul celebrate, but their career plans are uncertain. satisfy the country’s desperate need for technical talent. “After 3 decades of war, Afghanistan has lost one-and-a-half gener- ations of experts in all fi elds,” says Timor Saffary, the head of AUAF’s department of sci- ence and mathematics. “The intellectual elites either left the country or have passed away, leaving a huge vacuum.” Saffary earned Ph.D.s in both mathematics and physics and worked as a postdoctoral researcher in Germany before joining AUAF in 2009, and the 39-year-old native of Kabul hopes to be a part of the gen- eration who fi lls that vacuum. With the help of the United on August 13, 2012 States and other countries, Afghan academics are begin- ning to pick up the pieces. But a deadline looms: Inter- national military forces are preparing to leave the country HIGHER EDUCATION by the end of 2014, and it’s anybody’s guess what will happen after they are gone. “Many of the highest qualifi ed and talented academ- www.sciencemag.org Can Afghan Universities Recover ics are looking nervously at the 2014 with- drawal,” says Michael Petterson, a geologist From War, Taliban, and Neglect? at the University of Leicester in the United Kingdom who leads fi eld research and train- The demand for technical talent and outside funding is helping colleges get back on ing workshops in the region. “And who can their feet. But higher education is still not a priority blame them?” Downloaded from KABUL—Except for the armed guards in ating from high school in Kabul, Fazel left Afghan ivy body armor at the entrance, on the roof, and Afghanistan and eventually earned a Ph.D. -

Afghanistan: an Overview

Afghanistan: An Overview by Iraj Bashiri copyright 2002 General information Location and Terrain Afghanistan is a mountainous country centered primarily around the Hindu Kush range of mountains. Nearly three quarters of the country is covered by mountains that range in height anywhere between 3,000 to 4,000 feet. Afghanistan is bound to the north by the three republics of Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan; to the east by Tajikistan and China; to the south by Pakistan; and to the west by Iran. The inhabitants of the kingdom live in the river valleys created by the Kabul, Harirud, Andarab, and Hirmand rivers. The economy of Afghanistan is based on wet and dry farming as well as on herding. Afghanistan Overview Topography and Climate The weather in Afghanistan is varied depending on climatic zones. Generally, the winters are cold to mild (32 to 45 F.) and the summers (75 to 90 F.) are hot with no precipitation. No doubt Afghan topography and climate greatly impact transportation and social mobility and hampers the country's progress towards independence and nationhood. Ethnic Mix In 1893, when the Duran line was drawn and modern Afghanistan was created, the region of present-day Islamic Republic of Afghanistan was populated by two main ethnic groups: Indo-European and Turkish. Some pockets of Arab nomads, Hindus, and Jews also lived in the region mostly close to the Panj River valley. The Indo-European population was a continuation of the dominant Indo-Iranian branch in the north and west centered in the cities of Bukhara and Tehran, respectively. The Hindu Kush mountain divided this Indo-Iranian population into four ethnic zones: Pushtuns to the south and southeast; Tajiks to the northeast of the Hindu Kush range; Parsiwans to the west; and Baluch to the southwest The Pushtuns, who later (1950's) made an unsuccessful attempt at creating a Pushtunistan, numbered about 13,000,000. -

IT in Afghanistan

ICT in Afghanistan (two-way communication only) Siri Birgitte Uldal Muhammad Aimal Marjan 4. February 2004 Title NST report ICT in Afghanistan (Two way communication only) ISBN Number of pages Date Authors Siri Birgitte Uldal, NST Muhammad Aimal Marjan, Ministry of Communcation / Afghan Computer Science Association Summary Two years after Taliban left Kabul, there is about 172 000 telephones in Afghanistan in a country of assumed 25 mill inhabitants. The MoC has set up a three tier model for phone coverage, where the finishing of tier one and the start of tier two are under implementation. Today Kabul, Herat, Mazar-i-Sharif, Kandahar, Jalalabad, Kunduz has some access to phones, but not enough to supply the demand. Today there are concrete plans for extension to Khost, Pulekhomri, Sheberghan, Ghazni, Faizabad, Lashkergha, Taloqan, Parwan and Baglas. Beside the MoCs terrestrial network, two GSM vendors (AWCC and Roshan) have license to operate. The GoA has a radio network that reaches out to all provinces. 10 ISPs are registered. The .af domain was revitalized about a year ago, now 138 domains are registered under .af. Public Internet cafes exists in Kabul (est. 50), Mazar-i-Sharif (est. 10), Kandahar (est. 10) and Herat (est. 10), but NGOs has set up VSATs also in other cities. The MoC has plans for a fiber ring, but while the fiber ring may take some time, VSAT technology are utilized. Kabul University is likely offering the best higher education in the country. Here bachelor degrees in Computer Science are offered. Cisco has established a training centre in the same building offering a two year education in networking. -

Afghanistan-Pakistan Activities Quarterly Report XII (July-August-September 2005) Sustainable Development of Drylands Project IALC-UIUC

Afghanistan-Pakistan Activities Quarterly Report XII (July-August-September 2005) Sustainable Development of Drylands Project IALC-UIUC Introduction: Although specific accomplishments will be detailed below, a principal output this quarter was the Scope of Work (SoW) for fiscal year 2006 (FY 06), i.e. October 1, 2005 to September 30, 2006. The narrative portion of the SoW is attached to this report. Readers will note that this submission, which went to IALC headquarters on September 2, presents the progress made by our component thus far and the work ahead of us during year three of the current Cooperative Agreement and year four of the component we have titled “Human Capacity Development for the Agriculture Sector in Afghanistan”. The “Organized Short Courses” section of our FY 06 SoW states our intention to use core funds allocated through the Cooperative Agreement to support four one-month technical courses at an all-inclusive cost of $50,000 per course. As has been done in past years, we were planning to combine core funds with supplemental funds from other sources, allowing us to offer the usual six to eight short courses per year. We were informed by the Project Director that there would be a redistribution of core funds and a reduction in our allocation, from $375,000 in FY 05 to $300,000 this year. If these funds are not restored in full or in part, either from the core or additional Mission buy-in, this budget reduction will add significantly to the challenges we face in FY06 because we will need to generate this short course support from other sources. -

Education and Development in Afghanistan Challenges and Prospects

From: Uwe H. Bittlingmayer, Anne-Marie Grundmeier, Reinhart Kößler, Diana Sahrai, Fereschta Sahrai (eds.) Education and Development in Afghanistan Challenges and Prospects March 2019, 314 p., pb., numerous ill. 39,99 € (DE), 978-3-8376-3637-6 E-Book: PDF: 39,99 € (DE), ISBN 978-3-8394-3637-0 After years of military interventions, the current situation in Afghanistan is highly am- bivalent and partially contradictory – especially regarding the interplay of development, peace, security, education, and economy. Despite numerous initiatives, Afghanistan is still confronted with a poor security and economic condition. At the same time, enroll- ment numbers in schools and universities as well as the rate of academics reached a historical peak. This volume investigates the tension between these ambivalent developments. Sociol- ogists, political and cultural scientists along with development workers, educators, and artists from Germany and Afghanistan discuss the idea that education is primary for rebuilding a stable Afghan state and government. Uwe H. Bittlingmayer (Prof. Dr. phil.) teaches Sociology at the Institute of Sociology, University of Education Freiburg (Germany). Anne-Marie Grundmeier (Prof. Dr. rer. pol.) teaches and researches in the field of cultural sciences at the Institute of Everyday Life Culture, Sports and Health at the University of Education Freiburg. Reinhart Kößler (Prof. Dr. phil.) was director of the Arnold Bergstraesser Institute in Freiburg and is Visiting Professor and Research Associate at the Institute of Reconcilia- tion and Social Justice at the University of the Free State, South Africa. Diana Sahrai (Prof. Dr.) teaches inclusive education at the Institute for Special Needs Education, University of Applied Sciences and Arts Northwestern Switzerland, School of Education, Basel. -

BETWEEN PATRONAGE and REBELLION 1. the 1960S and 1970S

AFGHANISTAN RESEARCH AND EVALUATION UNIT Briefing Paper Series Dr Antonio Giustozzi February 2010 BETWEEN PATRONAGE AND REBELLION Student Politics in Afghanistan Contents Introduction 1. The 1960s and Student politics is an important aspect of politics in most countries 1970s ...................1 and its study is important to understanding the origins, development and future of political parties. Student politics is also relevant to elite 2. Post-2001: A different formation, because elites often take their first steps in the political arena environment .......... 4 through student organisations. In Afghanistan today, student politics 3. Post-2001: moves between two poles—patronage and rebellion—and through its Patronage and study we can catch a glimpse of the future of Afghan politics. Careerism ............. 6 Student politics in Afghanistan has not been the object of much 4. Post-2001: Rebellion scholarly attention, but we know that student politics in the 1960-70s Surging................12 had an important influence on the development of political parties, which in turn shaped Afghanistan’s entry into mass politics in the late 5. Conclusion and 1970-80s. The purpose of this study is therefore multiple: to fill a gap Implications ..........15 in the horizon of knowledge, to investigate the significance of changes Annex: Summary of in the student politics of today compared to several decades ago, and Cited Organisations ...16 finally to detect trends that might give us a hint of the Afghan politics of tomorrow. The research is based on approximately 100 interviews About the Author with students and political activists in Kabul, Herat, Mazar-i-Sharif and Jalalabad, as well as approximately 12 interviews with former Dr Antonio Giustozzi is student activists of the 1960-70s.