Falconer Thirstan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Trajectory of Three Marketing Boards in Canada: Gone, Going… and Curiously Persistent

The Trajectory of Three Marketing Boards in Canada: Gone, Going… and Curiously Persistent BRYAN P. SCHWARTZ INTRODUCTION overnment operated single-desk marketing boards were a feature of the Canadian agricultural economy for much of the 20th and G 21st centuries. However, their future viability and existence is now the subject of increasing criticism and doubt. This essay seeks to explain general trends by comparing and contrasting the past, present, and projected future of three schemes: the Canadian Wheat Board (CWB), the Freshwater Fish Marketing Corporation (FFMC), and the Canadian Dairy Commission (CDC). At one time the CWB was the largest grain marketing board in the world1, but after briefly being reduced to an option for producers as a dual-desk marketing board, the CWB has now been fully privatized. The FFMC has lost exclusive control in many jurisdictions, most recently ceasing to operate as a single-desk entity in Manitoba, and now operating as a single-desk only in the Northwest Territories. At the same time, the CDC continues to persevere despite both international pressure from partners to new free trade agreements that seek to reduce its authority, and domestic criticism that it is inefficient, hurts the disadvantaged, and stifles innovation. Professor and Asper Chair in International Business and Trade Law, Faculty of Law, University of Manitoba, Co-Editor-in-Chief, Manitoba Law Journal. 1 Brian Mayes, “Blame Canada: American Trade Complaints against the Canadian Wheat Board” (2002) 2 Asper Rev of Intl Bus and Trade L 135 at 135 [Mayes]. Three Marketing Boards in Canada 161 This essay reviews the theory of marketing boards and then compares the histories of the three different boards, the current developments in their operation, and the likely future of the boards or their successors. -

A Canadian Concept and Practice

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. IVERSION: CANADIAN CONCEPT AND PRACTICE Report on the First National Conference on Diversion October 23-26, 1977, Quebec City KE 8813 N3 1977r c.2 "Let us acknowledge that we are taking an old practice and that we're breeding new dimensions into it. -

World Bank Document

CONSULTATIVE GROUP ON INTERNATIONAL AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Fulfilling the Susan Whelan Promise: the Role for Public Disclosure Authorized 2003 Sir John Crawford Memorial Lecture Agricultural Research CGIAR Public Disclosure Authorized Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) is a strategic alliance of countries, international and regional organizations, and private foundations supporting 16 international agricultural research Centers that work with national agricultural systems, the private sector and civil society. The alliance mobilizes agricultural science to reduce poverty, foster human well-being, promote agricultural growth, and protect the environment. The CGIAR generates global public goods which are available to all. www.cgiar.org Fulfilling the Promise: the Role for Agricultural Research By Susan Whelan Minister for International Cooperation Canada 2003 Sir John Crawford Memorial Lecture Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research Nairobi, Kenya October 29, 2003 02 Ministers, Excellencies, ladies and gentlemen, good afternoon. Bonjour. Buenos Dias. Hamjambuni. Many distinguished speakers have stood behind this podium since the inaugural Sir John Crawford Memorial Lecture in 1985. It is with a sense of humility that I accept the honor to be numbered among them. As I do so, I would like to thank the Government of Australia for sponsoring this lecture and take a minute to reflect on the life and work of Sir John and on the reasons why funds, prizes and at least two lectures have been named in his honor. 03 I have not had the privilege of a personal acquaintance with Sir John. However, I admire the simple yet noble and profound proposition or objective on which this great gentleman built his sterling contribution to international development. -

Core 1..196 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 144 Ï NUMBER 025 Ï 2nd SESSION Ï 40th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, March 6, 2009 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) Also available on the Parliament of Canada Web Site at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1393 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, March 6, 2009 The House met at 10 a.m. Some hon. members: Yes. The Speaker: The House has heard the terms of the motion. Is it the pleasure of the House to adopt the motion? Prayers Some hon. members: Agreed. (Motion agreed to) GOVERNMENT ORDERS Mr. Mark Warawa (Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of the Environment, CPC) moved that Bill C-17, An Act to Ï (1005) recognize Beechwood Cemetery as the national cemetery of Canada, [English] be read the second time and referred to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development. NATIONAL CEMETERY OF CANADA ACT He said: Mr. Speaker, I would like to begin by seeking unanimous Hon. Jay Hill (Leader of the Government in the House of consent to share my time. Commons, CPC): Mr. Speaker, momentarily, I will be proposing a motion by unanimous consent to expedite passage through the The Speaker: Does the hon. member have unanimous consent to House of an important new bill, An Act to recognize Beechwood share his time? Cemetery as the national cemetery of Canada. However, before I Some hon. members: Agreed. propose my motion, which has been agreed to in advance by all parties, I would like to take a quick moment to thank my colleagues Mr. -

A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993

Canadian Military History Volume 24 Issue 2 Article 8 2015 A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993 Greg Donaghy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Greg Donaghy "A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993." Canadian Military History 24, 2 (2015) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993 A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993 GREG DONAGHY Abstract: Fifty years ago, Canadian peacekeepers landed on the small Mediterranean island of Cyprus, where they stayed for thirty long years. This paper uses declassified cabinet papers and diplomatic records to tackle three key questions about this mission: why did Canadians ever go to distant Cyprus? Why did they stay for so long? And why did they leave when they did? The answers situate Canada’s commitment to Cypress against the country’s broader postwar project to preserve world order in an era marked by the collapse of the European empires and the brutal wars in Algeria and Vietnam. It argues that Canada stayed— through fifty-nine troop rotations, 29,000 troops, and twenty-eight dead— because peacekeeping worked. Admittedly there were critics, including Prime Ministers Pearson, Trudeau, and Mulroney, who complained about the failure of peacemaking in Cyprus itself. -

The Long Reach of War: Canadian Records Management and the Public Archives

The Long Reach of War: Canadian Records Management and the Public Archives by Kathryn Rose A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2012 © Kathryn Rose 2012 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This thesis explores why the Public Archives of Canada, which was established in 1872, did not have the full authority or capability to collect the government records of Canada until 1966. The Archives started as an institution focused on collecting historical records, and for decades was largely indifferent to protecting government records. Royal Commissions, particularly those that reported in 1914 and 1962 played a central role in identifying the problems of records management within the growing Canadian civil service. Changing notions of archival theory were also important, as was the influence of professional academics, particularly those historians mandated to write official wartime histories of various federal departments. This thesis argues that the Second World War and the Cold War finally motivated politicians and bureaucrats to address records concerns that senior government officials had first identified during the time of Sir Wilfrid Laurier. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Geoffrey Hayes, for his enthusiasm, honesty and dedication to this process. I am grateful for all that he has done. -

Canada's Resource Curse: Too Much of a Good Thing Daniel Drache

______________________________________________________________________________ Canada’s Resource Curse: Too Much of a Good Thing Daniel Drache Professor, Department of Political Science and Associate Director of the Robarts Centre for Canadian Studies, York University, [email protected] Canada’s Resource Curse: Too Much of a Good Thing Daniel Drache1 Professor, Department of Political Science and Associate Director of the Robarts Centre for Canadian Studies, York University, [email protected] Abstract Canada has been both blessed and cursed by its vast resource wealth. Immense resource riches sends the wrong message to the political class that thinking and planning for tomorrow is unnecessary when record high global prices drive economic development at a frenetic pace. Short-termism, the loss of manufacturing competitiveness (‘the dutch disease’) and long term rent seeking behaviour from the corporate sector become, by default, the low policy standard. The paper contends that Canada is not a simple offshoot of Anglo-American, hyper-commercial capitalism but is subject to the recurring dynamics of social Canada and for this reason the Northern market model of capitalism needs its own theoretical articulation. Its distinguishing characteristic is that there is a large and growing role for mixed goods and non-negotiable goods in comparison to the United States even when the proactive role of the Canadian state had its wings clipped to a degree that stunned many observers. The paper also examines the uncoupling of Canadian and American economies driven in part by the global resource boom. The downside of the new staples export strategy is that hundreds of thousands of jobs have disappeared from Ontario and Quebec. -

Tories Keep Lead, but Liberal-NDP Merger Could Change Status

For Immediate Release Canadian Public Opinion Poll Page 1 of 8 CANADIAN POLITICAL PULSE Tories Keep Lead, But Liberal-NDP Merger Could Change Status Quo A single centre-left party would provide a real challenge to the Conservatives, but only if it is led by Jack Layton or Bob Rae. [TORONTO – May 31, 2010] – The Conservative Party is holding on to a comfortable lead in KEY FINDINGS Canada's political scene, a new Angus Reid Public Opinion poll has found. ¾ Voting Intention: Con. 35%, Lib. 27%, NDP 19%, BQ 9%, Grn. 8%. The online survey of a representative national sample of 2,022 Canadians also looked at the ¾ Scenarios with a merged Liberal / NDP: way the electorate would behave in the event of a Six-point lead over the Tories under merger between the Liberal Party and the New Layton, Tie under Rae, Second place Democratic Party (NDP) under three different under Ignatieff prospective leaders. ¾ Approval Rating: Layton 30%, Harper Voting Intention 29%, Ignatieff 13%. Across the country, 35 per cent of decided voters ¾ Momentum: Layton -3, Harper -24, (unchanged since late April) would cast a ballot Ignatieff -28. for the Conservative candidate in their riding if a new federal election took place today. Full topline results are at the end of this release. The Liberal Party is second with 27 per cent (-1), From May 25 to May 27, 2010, Angus Reid Public Opinion conducted an online survey among 2,022 randomly selected just one point ahead of the proportion of the vote Canadian adults who are Angus Reid Forum panelists. -

A Perennial Problem”: Canadian Relations with Hungary, 1945-65

Hungarian Studies Review, Vol. XLIII, Nos. 1-2 (Spring-Fall, 2016) “A Perennial Problem”: Canadian Relations with Hungary, 1945-65 Greg Donaghy1 2014-15 marks the 50th anniversary of the establishment of Canadian- Hungarian diplomatic relations. On January 14, 1965, under cold blue skies and a bright sun, János Bartha, a 37-year-old expert on North Ameri- can affairs, arrived in the cozy, wood paneled offices of the Secretary of State for External Affairs, Paul Martin Sr. As deputy foreign minister Marcel Cadieux and a handful of diplomats looked on, Bartha presented his credentials as Budapest’s first full-time representative in Canada. Four months later, on May 18, Canada’s ambassador to Czechoslovakia, Mal- colm Bow, arrived in Budapest to present his credentials as Canada’s first non-resident representative to Hungary. As he alighted from his embassy car, battered and dented from an accident en route, with its fender flag already frayed, grey skies poured rain. The contrasting settings in Ottawa and Budapest are an apt meta- phor for this uneven and often distant relationship. For Hungary, Bartha’s arrival was a victory to savor, the culmination of fifteen years of diplo- matic campaigning and another step out from beneath the shadows of the postwar communist take-over and the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. For Canada, the benefits were much less clear-cut. In the context of the bitter East-West Cold War confrontation, closer ties with communist Hungary demanded a steep domestic political price in exchange for a bundle of un- certain economic, consular, and political gains. -

The 2006 Federal Liberal and Alberta Conservative Leadership Campaigns

Choice or Consensus?: The 2006 Federal Liberal and Alberta Conservative Leadership Campaigns Jared J. Wesley PhD Candidate Department of Political Science University of Calgary Paper for Presentation at: The Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan May 30, 2007 Comments welcome. Please do not cite without permission. CHOICE OR CONSENSUS?: THE 2006 FEDERAL LIBERAL AND ALBERTA CONSERVATIVE LEADERSHIP CAMPAIGNS INTRODUCTION Two of Canada’s most prominent political dynasties experienced power-shifts on the same weekend in December 2006. The Liberal Party of Canada and the Progressive Conservative Party of Alberta undertook leadership campaigns, which, while different in context, process and substance, produced remarkably similar outcomes. In both instances, so-called ‘dark-horse’ candidates emerged victorious, with Stéphane Dion and Ed Stelmach defeating frontrunners like Michael Ignatieff, Bob Rae, Jim Dinning, and Ted Morton. During the campaigns and since, Dion and Stelmach have been labeled as less charismatic than either their predecessors or their opponents, and both of the new leaders have drawn skepticism for their ability to win the next general election.1 This pair of surprising results raises interesting questions about the nature of leadership selection in Canada. Considering that each race was run in an entirely different context, and under an entirely different set of rules, which common factors may have contributed to the similar outcomes? The following study offers a partial answer. In analyzing the platforms of the major contenders in each campaign, the analysis suggests that candidates’ strategies played a significant role in determining the results. Whereas leading contenders opted to pursue direct confrontation over specific policy issues, Dion and Stelmach appeared to benefit by avoiding such conflict. -

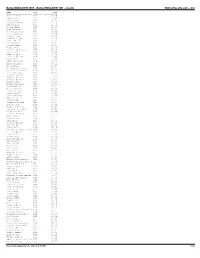

Bolderboulder 2005 - Bolderboulder 10K - Results Onlineraceresults.Com

BolderBOULDER 2005 - BolderBOULDER 10K - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Michael Aish M28 30:29 Jesus Solis M21 30:45 Nelson Laux M26 30:58 Kristian Agnew M32 31:10 Art Seimers M32 31:51 Joshua Glaab M22 31:56 Paul DiGrappa M24 32:14 Aaron Carrizales M27 32:23 Greg Augspurger M27 32:26 Colby Wissel M20 32:36 Luke Garringer M22 32:39 John McGuire M18 32:42 Kris Gemmell M27 32:44 Jason Robbie M28 32:47 Jordan Jones M23 32:51 Carl David Kinney M23 32:51 Scott Goff M28 32:55 Adam Bergquist M26 32:59 trent r morrell M35 33:02 Peter Vail M30 33:06 JOHN HONERKAMP M29 33:10 Bucky Schafer M23 33:12 Jason Hill M26 33:15 Avi Bershof Kramer M23 33:17 Seth James DeMoor M19 33:20 Tate Behning M23 33:22 Brandon Jessop M26 33:23 Gregory Winter M26 33:25 Chester G Kurtz M30 33:27 Aaron Clark M18 33:28 Kevin Gallagher M25 33:30 Dan Ferguson M23 33:34 James Johnson M36 33:38 Drew Tonniges M21 33:41 Peter Remien M25 33:45 Lance Denning M43 33:48 Matt Hill M24 33:51 Jason Holt M18 33:54 David Liebowitz M28 33:57 John Peeters M26 34:01 Humberto Zelaya M30 34:05 Craig A. Greenslit M35 34:08 Galen Burrell M25 34:09 Darren De Reuck M40 34:11 Grant Scott M22 34:12 Mike Callor M26 34:14 Ryan Price M27 34:15 Cameron Widoff M35 34:16 John Tribbia M23 34:18 Rob Gilbert M39 34:19 Matthew Douglas Kascak M24 34:21 J.D. -

The Roots of French Canadian Nationalism and the Quebec Separatist Movement

Copyright 2013, The Concord Review, Inc., all rights reserved THE ROOTS OF FRENCH CANADIAN NATIONALISM AND THE QUEBEC SEPARATIST MOVEMENT Iris Robbins-Larrivee Abstract Since Canada’s colonial era, relations between its Fran- cophones and its Anglophones have often been fraught with high tension. This tension has for the most part arisen from French discontent with what some deem a history of religious, social, and economic subjugation by the English Canadian majority. At the time of Confederation (1867), the French and the English were of almost-equal population; however, due to English dominance within the political and economic spheres, many settlers were as- similated into the English culture. Over time, the Francophones became isolated in the province of Quebec, creating a densely French mass in the midst of a burgeoning English society—this led to a Francophone passion for a distinct identity and unrelent- ing resistance to English assimilation. The path to separatism was a direct and intuitive one; it allowed French Canadians to assert their cultural identities and divergences from the ways of the Eng- lish majority. A deeper split between French and English values was visible before the country’s industrialization: agriculture, Ca- Iris Robbins-Larrivee is a Senior at the King George Secondary School in Vancouver, British Columbia, where she wrote this as an independent study for Mr. Bruce Russell in the 2012/2013 academic year. 2 Iris Robbins-Larrivee tholicism, and larger families were marked differences in French communities, which emphasized tradition and antimaterialism. These values were at odds with the more individualist, capitalist leanings of English Canada.