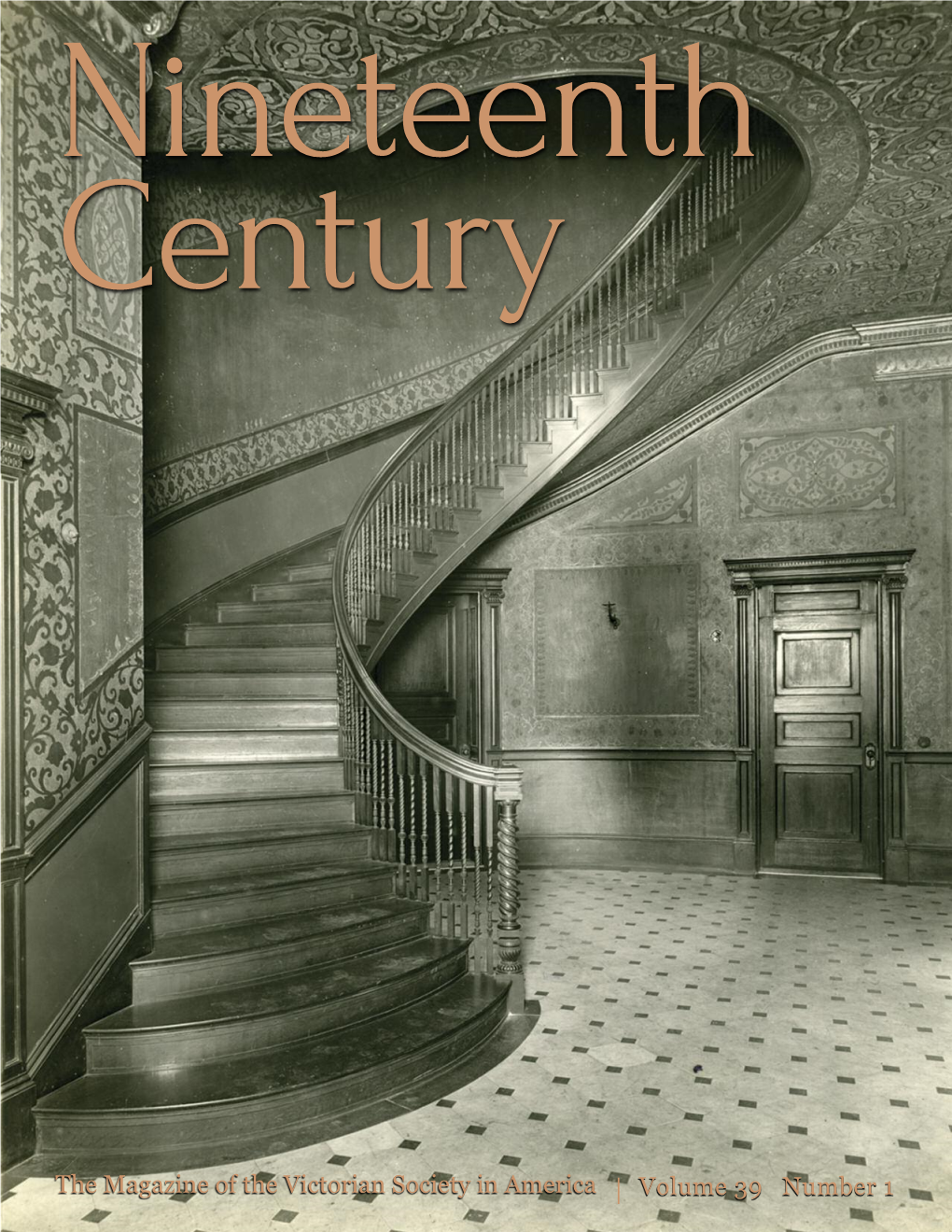

The Magazine of the Victorian Society in America Volume 39 Number 1 Editorial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egacy Exploring the History of the Garrett-Jacobs Mansion 2021

he egacy Exploring the history of the Garrett-Jacobs Mansion 2021 GARRETT-JACOBS MANSION ENDOWMENT FUND, INC. Becoming Mary Frick Garrett Jacobs Bernadette Flynn Low, PhD The Frick Family and Victorian Era Values Mary Sloan Frick was born in 1851 and grew up in a privileged position as one of the prominent Frick family of Baltimore. Mary’s father, William Frederick Frick, descended from John Frick, an immigrant from Holland who helped establish Germantown, Pennsylvania. John’s son, Peter Frick, settled in Baltimore, where his own son, William Frick, became an esteemed judge and community leader. William had several children, including William Frederick, Mary’s father. Like his father, William Frederick studied law and graduated from Harvard Law School. Returning to Baltimore, he became one of the first four members of the Baltimore Bar. Mary, appreciative of her heritage, also traced the ancestry of her mother, Ann Elizabeth Swan, to Sir George Yeardley, the first governor of Virginia, and General John Swan, a Scottish immigrant who served in the Revolutionary War and was promoted by General George Washington. After the war, Swan was honored with a Mary Frick Garrett Jacobs. parcel of land by a grateful nation. There he built an estate near Catonsville, Maryland, that would later be named Uplands. (William Frederick and Ann would gift Uplands to Mary The Garretts never traveled and her first husband, Robert Garrett, upon overseas without their Saint their marriage.) Bernard dogs. However, at least once, they neglected The Frick family rooted themselves in to bring their dogs back the values of the Victorian era. -

(APN019-090-026) Santa Barbara, California

PHASE 1-2 HISTORIC SITES/STRUCTURES REPORT For 1809 Mira Vista Avenue (APN019-090-026) Santa Barbara, California Prepared for: John and Daryl Stegall c/o Tom Henson Becker, Henson, Niksto Architects 34 West Mission Street Santa Barbara, CA 93101 (805-682-3636 Prepared by POST/HAZELTINE ASSOCIATES 2607 Orella Street Santa Barbara, CA 93105 (805) 682-5751 [email protected] April 25, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section__________________________________________________________________Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................ 1 2.0 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................... 1 3.0 PREVIOUS STUDIES AND DESIGNATIONS.................................................................2 4.0 DOCUMENTS REVIEW .................................................................................................. 2 5.0 ENVIRONMENTAL AND NEIGHBORHOOD SETTING.................................................. 2 PHASE ONE SECTION .....................................................................................................7 6.0 SITE DESCRIPTION ........................................................................................................ 7 6.1 House ................................................................................................................... 10 6.1.1 North elevation (Street façade, facing Mira Vista Avenue)..................... 10 6.1.2 South Elevation (Rear elevation, -

Destination of the Month: Tangier, Morocco

Destination of the Month: Tangier, Morocco A mere eight miles across the Strait of Gibraltar from Spain, Richard Allemanfinds an exotic new world in a legendary North African city that has everything from cool cafés and new boutique hotels to glorious beaches, a fascinating history, and the world’s most famous kasbah. The Best Beaches Boasting a stellar location on the Strait of Gibraltar, with the Mediterranean to the east and the Atlantic to the west, Tangier is one of the world’s great beach towns. The city itself sits on a sweeping expanse of sand that’s edged with beach clubs, cafés, and discos. The town beach, favored by local youths for swimming and soccer, and with its crowds and sometimes polluted water, is not recommended for tourists, but there are glorious alternatives. This season, the plage du jour isPlage de Sidi Kacem, about 20 kilometers west of town, beyond the Cap Spartel lighthouse and the Mirage resort. Here, in a garden by the sea, local restaurateurs Rémi Tulloue and Philippe Morin have created the chic French bistrot L’Océan ( 05.3933.8137), an idyllic spot for a long leisurely lunch. For the serious surf set, on the same beach Philippe and Rémi have recently opened Club de Plage,with chaise longues and thatched umbrellas right on the sand. For the ultimate beach experience, however, drive down to Asilah, an enchanting little coastal town about an hour south of Tangier, where a few kilometers away, a rough, sandy road leads to Paradise Beach—a cliff-backed beauty, reminiscent of the Greek islands, with shack cafés that rent umbrellas and chaises and serve fresh grilled fish and simple tagines (stews) made with chicken and bright local veggies. -

In 1893, the Tiffany Chapel Was Created for the Chicago World's Fair (World's Columbian Exposition). Louis Comf

In 1893, the Tiffany Chapel was created for the Chicago world's fair (World's Columbian Exposition). Louis Comfort Tiffany's exhibit at the fair was developed by the Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company. The exhibit was installed at the Tiffany & Co. pavilion in the Manufacturers and Liberal Arts Building. Today, the chapel can be seen at the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art in Winter Park, Florida. The chapel in its form and design is one of the most beautiful that my wife and I have seen. The room, except for two of the four benches is in its original state as at the exhibit in Chicago. From its "decorative moldings, altar floor, carved plaster arches, marble and glass‐mosaic furnishings, four leaded glass windows, sixteen glass‐mosaic encrusted columns (1,000 pounds each) and a ten‐foot by eight‐foot electrified chandelier. The nonhistorical parts of the chapel include walls, nave floor, and ceilings." <Morse Museum> <morsemusem.org> The museum staff commented to us that many people who enter the chapel are so moved by the room's beauty that many sit on the benches and pray. After the Chicago fair, he moved the chapel to his Tiffany studios. It then was purchased by a wealthy woman and installed in 1898 in the crypt of New York's Cathedral Church of Saint John Divine. <Morse Museum> <morsemusem.org> It was used for about ten years but fell into disrepair, due to water damage. Tiffany became concerned and acquired the chapel in 1916. He moved and reinstalled the chapel at his Long Island estate called Laurelton Hall. -

Louis Comfort Tiffany: a Bibliography, Relevant to the Man, His Work, and His Oyster Bay, Long Island, Home.”

Please cite as: Spinzia, Judith Ader, “Louis Comfort Tiffany: A Bibliography, Relevant to the Man, His Work, and His Oyster Bay, Long Island, Home.” www.spinzialongislandestates.com Louis Comfort Tiffany: A Bibliography Relevant to the Man, His Work, and His Oyster Bay, Long Island, Home compiled by Judith Ader Spinzia . The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum, Winter Park, FL, has photographs of Laurelton Hall. Harvard Law School, Manuscripts Division, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, has Charles Culp Burlingham papers. Sterling Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT, has papers and correspondence filed under the Mitchell–- Tiffany papers. Savage, M. Frederick. Laurelton Hall Inventory, 1919. Entire inventory can be found in the Long Island Studies Institute, Hofstra University, Hempstead, LI. The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe College, Cambridge, MA, has Edith Banfield Jackson papers. Tiffany & Company archives are in Parsippany, NJ. “American Country House of Louis Comfort Tiffany.” International Studio 33 (February 1908):294-96. “Artists Heaven; Long Island Estate of Louis Tiffany To Be an Artists' Home.” Review 1 (November 1, 1919):533. Baal-Teshuva, Jacob. Louis Comfort Tiffany. New York: Taschen Publishing Co., 2001. Bedford, Stephen and Richard Guy Wilson. The Long Island Country House, 1870-1930. Southampton, NY: The Parrish Art Museum, 1988. Bing, Siegfried. Artistic America, Tiffany Glass, and Art Nouveau. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, [1895-1903] 1970. [reprint, edited by Robert Koch] Bingham, Alfred Mitchell. The Tiffany Fortune and Other Chronicles of a Connecticut Family. Chestnut Hill, MA: Abeel and Leet Publishers, 1996. Brownell, William C. “The Younger Painters of America.” Scribner's Monthly July 1881:321-24. Burke, Doreen Bolger. -

View of the Many Ways in Which the Ohio Move Ment Paralled the National Movement in Each of the Phases

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While tf.; most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in "sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

The National Genealogical Society Quarterly

Consolidated Contents of The National Genealogical Society Quarterly Volumes 1-90; April, 1912 - December, 2002 Compiled by, and Copyright © 2011-2013 by Dale H. Cook This file is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material directly from plymouthcolony.net, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement. Please contact [email protected] so that legal action can be undertaken. Any commercial site using or displaying any of my files or web pages without my express written permission will be charged a royalty rate of $1000.00 US per day for each file or web page used or displayed. [email protected] Revised August 29, 2013 As this file was created for my own use a few words about the format of the entries are in order. The entries are listed by NGSQ volume. Each volume is preceded by the volume number and year in boldface. Articles that are carried across more than one volume have their parts listed under the applicable volumes. This entry, from Volume 19, will illustrate the format used: 19 (1931):20-24, 40-43, 48, 72-76, 110-111 (Cont. from 18:92, cont. to 20:17) Abstracts of Revolutionary War Pension Applications Jessie McCausland (Mrs. A. Y.) Casanova The first line of an entry for an individual article or portion of a series shows the NGSQ pages for an article found in that volume. When a series spans more than one volume a note in parentheses indicates the volume and page from which or to which it is continued. -

Frederick Ayer Mansion

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 AVER, FREDERICK, MANSION Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Frederick Ayer Mansion Other Name/Site Number: Bayridge Residence and Cultural Center 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 395 Commonwealth Avenue Not for publication: City/Town: Boston Vicinity: State: MA County: Suffolk Code: 025 Zip Code: 02215-2322 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): _X Public-Local: __ District: __ Public-State: __ Site: __ Public-Federal: Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 __ buildings __ sites __ structures __ objects 1 0 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: J_ Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 AYER, FREDERICK, MANSION Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Tiffany Studios Designs

GALLERY VIII TIFFANY STUDIOS DESIGNS OBJECT GUIDE Teams of talented artists and artisans in multiple locations—from workshops in Manhattan to a glass-and-metal factory in Corona, Queens—enabled Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933) to meet growing demand for works that reflected boundless variety, experimentation, and innovation. Artfully designed, high-quality objects were the hallmark of Tiffany’s companies over the course of sixty years. All objects in this exhibition were made by artists working under Tiffany’s supervision at one of his firms in New York City. 1) Top to bottom: Tiffany Studios ecclesiastical workshop, c. 1918 Tiffany Studios building, Albumen print c. 1910 (2009-007:003) 355 Madison Avenue, New York City Tiffany Studios mosaic workers, Photographic c. 1910 reproduction Albumen print Gift of Mrs. George D. James (2010-008:003) (2017-151) 3) Top to bottom: Tiffany Studios factory building, c. 1910 Tiffany Studios showroom, c. 1927 Corona, Queens, New York 391 Madison Avenue, Photographic print from New York City glass-plate negative Photographic reproduction (2001-042:029) (2000-024:004) 2) Top to bottom: Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company receipt, c. 1901 Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company Ink on printed paper building, c. 1895 (2009-017:006) Fourth Avenue, New York City Photographic reproduction 4) Top to bottom: 7) Top to bottom: Baptismal font design, c. 1910 Window design, c. 1910 Watercolor, gouache on paper Rosehill Mausoleum, Marks: TIFFANY [conjoined TS] Chicago STUDIOS / ECCLESIASTICAL Watercolor on paper DEPARTMENT / NEW YORK Marks: #3880 / (2002-009) [illegible] / Suggestion No. 2 for / Landscape Baptismal font design, Window Rosehill c. -

Frank Furness Printed by Official Offset Corp

Nineteenth Ce ntury The Magazine of the Victorian Society in America Volume 37 Number 1 Nineteenth Century hhh THE MAGAZINE OF THE VICTORIAN SOCIETY IN AMERICA VOLuMe 37 • NuMBer 1 SPRING 2017 Editor Contents Warren Ashworth Consulting Editor Sara Chapman Bull’s Teakwood Rooms William Ayres A LOST LETTER REVEALS A CURIOUS COMMISSION Book Review Editor FOR LOCkwOOD DE FOREST 2 Karen Zukowski Roberta A. Mayer and Susan Condrick Managing Editor / Graphic Designer Wendy Midgett Frank Furness Printed by Official Offset Corp. PERPETUAL MOTION AND “THE CAPTAIN’S TROUSERS” 10 Amityville, New York Michael J. Lewis Committee on Publications Chair Warren Ashworth Hart’s Parish Churches William Ayres NOTES ON AN OVERLOOkED AUTHOR & ARCHITECT Anne-Taylor Cahill OF THE GOTHIC REVIVAL ERA 16 Christopher Forbes Sally Buchanan Kinsey John H. Carnahan and James F. O’Gorman Michael J. Lewis Barbara J. Mitnick Jaclyn Spainhour William Noland Karen Zukowski THE MAkING OF A VIRGINIA ARCHITECT 24 Christopher V. Novelli For information on The Victorian Society in America, contact the national office: 1636 Sansom Street Philadelphia, PA 19103 (215) 636-9872 Fax (215) 636-9873 [email protected] Departments www.victoriansociety.org 38 Preservation Diary THE REGILDING OF SAINT-GAUDENS’ DIANA Cynthia Haveson Veloric 42 The Bibliophilist 46 Editorial 49 Contributors Jo Anne Warren Richard Guy Wilson 47 Milestones Karen Zukowski A PENNY FOR YOUR THOUGHTS Anne-Taylor Cahill Cover: Interior of richmond City Hall, richmond, Virginia. Library of Congress. Lockwood de Forest’s showroom at 9 East Seventeenth Street, New York, c. 1885. (Photo is reversed to show correct signature and date on painting seen in the overmantel). -

Practices of Territorial Marketing in Morocco: a Study of the Experience of Tangier

IBIMA Publishing Journal of North African Research in Business http://www.ibimapublishing.com/journals/JNARB/jnarb.html Vol. 2016 (2016), Article ID 793075 , 22 Pages DOI: 10.5171/2016. 793075 Research Article Practices of Territorial Marketing in Morocco: A Study of the Experience of Tangier Fadoua Laghzaoui and Mostafa Abakouy University of Abdelmalek Essaâdi, Tangier, Morocco Correspondence should be addressed to: Mostafa Abakouy; [email protected] Received date : 3 March 2015; Accepted date : 27 November 2015; Published date : 11 May 2016 Academic editor: Ikram Radhouane Fgaier Copyright © 2016. Fadoua Laghzaoui And Mostafa Abakouy. Distributed under Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 Abstrac t The purpose of this research is to discuss the territorial marketing and analyze its application to the city of Tangier. Our approach was, firstly, to seize the regional marketing effort of Tangier in its temporal dynamics (Past-present-future) and, secondly, to decline this marketing: marketing to residents, tourism marketing and marketing to investors. The main results of our research show that marketing as designed and conducted in Tangier is insufficient and unsatisfactory. Such shortcomings have led us to formulate recipes that can improve the image, attractiveness and competitiveness of the city. Keywords: Territorial Marketing, Tangier, Tourism Marketing, Attractive Investment, Welfare of Citizens Context and the Problematic of De one can predict that the evolution of Research Morocco rests on the region and that de state with territorial organization is In Morocco, the affirmation of the existence substituted for the unitary state. Our of territorial regimes throughout time has research on the marketing of regions will corresponded not only to periods of be seen directly in this perspective. -

“India in America” a Curatorial Conversation on the Work and Practice of Lockwood De Forest and the Ahmedabad Wood Carving Company

Vol 9, No 1 (2021) | ISSN 2153-5914 (online) | DOI 10.5195/contemp/2021.314 http://contemporaneity.pitt.edu “India in America” A Curatorial Conversation on the Work and Practice of Lockwood de Forest and The Ahmedabad Wood Carving Company Nina Blomfield and Katie Loney Conversation A curatorial conversation between Nina Blomfield and Katie Loney on the work and practice of Lockwood de Forest and The Ahmedabad Wood Carving Company. This conversation is based on a public conversation held on October 3, 2019 at the University of Pittsburgh. About the Authors Nina Blomfield is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History of Art at Bryn Mawr College. She holds a B.A. in history from Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand and an M.A, from Bryn Mawr College. Her research focuses on nineteenth-century architecture and design history, the material culture of the home, and networks of consumption in the decorative arts. She is working on a dissertation that explores the intimacy of cultural encounter in late- nineteenth-century interior decorating and the role of the domestic interior in engendering, embodying, and preserving complex social and artistic relationships. Katie Loney is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History of Art and Architecture at the University of Pittsburgh. Her research examines nineteenth-century American art and design, with a focus on processes of making, international art markets, collecting histories, and Orientalism. She currently holds an Andrew W. Mellon Predoctoral Fellowship at the University of Pittsburgh, where she is writing her dissertation “Lockwood de Forest, The Ahmedabad Wood Carving Company, and the Global Circulation of Luxury Goods.” Her work has been supported by the World History Center, the Terra Foundation for American Art, and CASVA.