Dilemmas and Orientations of Greek Policy in Macedonia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vladimir Paounovsky

THE B ULGARIAN POLICY TTHE BB ULGARIAN PP OLICY ON THE BB ALKAN CCOUNTRIESAND NN ATIONAL MM INORITIES,, 1878-19121878-1912 Vladimir Paounovsky 1.IN THE NAME OF THE NATIONAL IDEAL The period in the history of the Balkan nations known as the “Eastern Crisis of 1875-1879” determined the international political development in the region during the period between the end of 19th century and the end of World War I (1918). That period was both a time of the consolidation of and opposition to Balkan nationalism with the aim of realizing, to a greater or lesser degree, separate national doctrines and ideals. Forced to maneuver in the labyrinth of contradictory interests of the Great Powers on the Balkan Peninsula, the battles among the Balkan countries for superiority of one over the others, led them either to Pyrrhic victories or defeats. This was particularly evident during the 1912-1913 Balkan Wars (The Balkan War and The Interallied War) and World War I, which was ignited by a spark from the Balkans. The San Stefano Peace Treaty of 3 March, 1878 put an end to the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878). According to the treaty, an independent Bulgarian state was to be founded within the ethnographic borders defined during the Istanbul Conference of December 1876; that is, within the framework of the Bulgarian Exarchate. According to the treaty the only loss for Bulgaria was the ceding of North Dobroujda to Romania as compensa- tion for the return of Bessarabia to Russia. The Congress of Berlin (June 1878), however, re-consid- ered the Peace Treaty and replaced it with a new one in which San Stefano Bulgaria was parceled out; its greater part was put under Ottoman control again while Serbia was given the regions around Pirot and Vranya as a compensation for the occupation of Novi Pazar sancak (administrative district) by Austro-Hun- - 331 - VLADIMIR P AOUNOVSKY gary. -

Annex REPORT for 2019 UNDER the “HEALTH CARE” PRIORITY of the NATIONAL ROMA INTEGRATION STRATEGY of the REPUBLIC of BULGAR

Annex REPORT FOR 2019 UNDER THE “HEALTH CARE” PRIORITY of the NATIONAL ROMA INTEGRATION STRATEGY OF THE REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA 2012 - 2020 Operational objective: A national monitoring progress report has been prepared for implementation of Measure 1.1.2. “Performing obstetric and gynaecological examinations with mobile offices in settlements with compact Roma population”. During the period 01.07—20.11.2019, a total of 2,261 prophylactic medical examinations were carried out with the four mobile gynaecological offices to uninsured persons of Roma origin and to persons with difficult access to medical facilities, as 951 women were diagnosed with diseases. The implementation of the activity for each Regional Health Inspectorate is in accordance with an order of the Minister of Health to carry out not less than 500 examinations with each mobile gynaecological office. Financial resources of BGN 12,500 were allocated for each mobile unit, totalling BGN 50,000 for the four units. During the reporting period, the mobile gynecological offices were divided into four areas: Varna (the city of Varna, the village of Kamenar, the town of Ignatievo, the village of Staro Oryahovo, the village of Sindel, the village of Dubravino, the town of Provadia, the town of Devnya, the town of Suvorovo, the village of Chernevo, the town of Valchi Dol); Silistra (Tutrakan Municipality– the town of Tutrakan, the village of Tsar Samuel, the village of Nova Cherna, the village of Staro Selo, the village of Belitsa, the village of Preslavtsi, the village of Tarnovtsi, -

1 I. ANNEXES 1 Annex 6. Map and List of Rural Municipalities in Bulgaria

I. ANNEXES 1 Annex 6. Map and list of rural municipalities in Bulgaria (according to statistical definition). 1 List of rural municipalities in Bulgaria District District District District District District /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality Blagoevgrad Vidin Lovech Plovdiv Smolyan Targovishte Bansko Belogradchik Apriltsi Brezovo Banite Antonovo Belitsa Boynitsa Letnitsa Kaloyanovo Borino Omurtag Gotse Delchev Bregovo Lukovit Karlovo Devin Opaka Garmen Gramada Teteven Krichim Dospat Popovo Kresna Dimovo Troyan Kuklen Zlatograd Haskovo Petrich Kula Ugarchin Laki Madan Ivaylovgrad Razlog Makresh Yablanitsa Maritsa Nedelino Lyubimets Sandanski Novo Selo Montana Perushtitsa Rudozem Madzharovo Satovcha Ruzhintsi Berkovitsa Parvomay Chepelare Mineralni bani Simitli Chuprene Boychinovtsi Rakovski Sofia - district Svilengrad Strumyani Vratsa Brusartsi Rodopi Anton Simeonovgrad Hadzhidimovo Borovan Varshets Sadovo Bozhurishte Stambolovo Yakoruda Byala Slatina Valchedram Sopot Botevgrad Topolovgrad Burgas Knezha Georgi Damyanovo Stamboliyski Godech Harmanli Aitos Kozloduy Lom Saedinenie Gorna Malina Shumen Kameno Krivodol Medkovets Hisarya Dolna banya Veliki Preslav Karnobat Mezdra Chiprovtsi Razgrad Dragoman Venets Malko Tarnovo Mizia Yakimovo Zavet Elin Pelin Varbitsa Nesebar Oryahovo Pazardzhik Isperih Etropole Kaolinovo Pomorie Roman Batak Kubrat Zlatitsa Kaspichan Primorsko Hayredin Belovo Loznitsa Ihtiman Nikola Kozlevo Ruen Gabrovo Bratsigovo Samuil Koprivshtitsa Novi Pazar Sozopol Dryanovo -

Kresna Gorge and Struma Motorway Lot 3.2 (Bulgaria)

Kresna Gorge and Struma Motorway Lot 3.2 (Bulgaria) Malina Kroumova Representative of the Bulgarian Government 38th Meeting of the Standing Committee of the Bern Convention November 2018 Struma Motorway . The busiest international road going through Bulgaria in the North-South direction . Part of the core TEN-T network, Orient-East/Med corridor . Located in Southwestern Bulgaria (150 km long) . Top priority infrastructure project for the EU . Site of national importance 2 Kresna Gorge - Issues . Serious and frequent accidents along the existing road . Mortality of wild animals on the road, fragmentation of habitats . Travel time, comfort and reliability of road users . Safety of the population and environmental issues in Kresna Town 3 EIA/AA Decision . Five alternatives were equally and thoroughly assessed . Only Long Tunnel Alternative and Eastern Alternative G10.50 were found to be compatible with the conservation objectives of both protected areas . Eastern Alternative G10.50 has clear advantage over 8 environmental components and factors of human health . The Minister of Environment and Water issued EIA Decision No 3-3/2017 approving Eastern Alternative G10.50 . Mandatory conditions and measures for implementation at all stages of the realization of G10.50 4 EIA/AA Decision - Mitigation Measures . Assessed in the EIA/AA . Fencing and passage facilities – technically feasible . Elimination of the risk of mortality and reduction of the barrier effect . Monitoring of the population (4 of the potentially most affected species) 5 Alternatives addressed in the NGOs’ report . Eastern Alternative G20 . Full Tunnel Alternative . Eastern Bypass (the so called “Votan Project”) . Eastern Tunnel Alternative (combination of Lot 3.2 with the existing railway line) 6 Eastern Alternative G20 . -

The Shaping of Bulgarian and Serbian National Identities, 1800S-1900S

The Shaping of Bulgarian and Serbian National Identities, 1800s-1900s February 2003 Katrin Bozeva-Abazi Department of History McGill University, Montreal A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 Contents 1. Abstract/Resume 3 2. Note on Transliteration and Spelling of Names 6 3. Acknowledgments 7 4. Introduction 8 How "popular" nationalism was created 5. Chapter One 33 Peasants and intellectuals, 1830-1914 6. Chapter Two 78 The invention of the modern Balkan state: Serbia and Bulgaria, 1830-1914 7. Chapter Three 126 The Church and national indoctrination 8. Chapter Four 171 The national army 8. Chapter Five 219 Education and national indoctrination 9. Conclusions 264 10. Bibliography 273 Abstract The nation-state is now the dominant form of sovereign statehood, however, a century and a half ago the political map of Europe comprised only a handful of sovereign states, very few of them nations in the modern sense. Balkan historiography often tends to minimize the complexity of nation-building, either by referring to the national community as to a monolithic and homogenous unit, or simply by neglecting different social groups whose consciousness varied depending on region, gender and generation. Further, Bulgarian and Serbian historiography pay far more attention to the problem of "how" and "why" certain events have happened than to the emergence of national consciousness of the Balkan peoples as a complex and durable process of mental evolution. This dissertation on the concept of nationality in which most Bulgarians and Serbs were educated and socialized examines how the modern idea of nationhood was disseminated among the ordinary people and it presents the complicated process of national indoctrination carried out by various state institutions. -

Blood Ties: Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878

BLOOD TIES BLOOD TIES Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 I˙pek Yosmaog˘lu Cornell University Press Ithaca & London Copyright © 2014 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2014 by Cornell University Press First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 2014 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yosmaog˘lu, I˙pek, author. Blood ties : religion, violence,. and the politics of nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 / Ipek K. Yosmaog˘lu. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5226-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8014-7924-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Macedonia—History—1878–1912. 2. Nationalism—Macedonia—History. 3. Macedonian question. 4. Macedonia—Ethnic relations. 5. Ethnic conflict— Macedonia—History. 6. Political violence—Macedonia—History. I. Title. DR2215.Y67 2013 949.76′01—dc23 2013021661 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Paperback printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Josh Contents Acknowledgments ix Note on Transliteration xiii Introduction 1 1. -

Vernacular Religion in Diaspora: a Case Study of the Macedono-Bulgarian Group in Toronto

Vernacular Religion in Diaspora: a Case Study of the Macedono-Bulgarian Group in Toronto By Mariana Dobreva-Mastagar A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Trinity College and the Theological Department of the Toronto School of Theology In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology awarded by the University of St. Michael's College © Copyright by Mariana Dobreva-Mastagar 2016 Vernacular Religion in Diaspora: a case Study of the Macedono-Bulgarian group in Toronto PhD 2016 Mariana Dobreva-Mastagar University of St.Michael’s College Abstract This study explores how the Macedono-Bulgarian and Bulgarian Eastern Orthodox churches in Toronto have attuned themselves to the immigrant community—specifically to post-1990 immigrants who, while unchurched and predominantly secular, have revived diaspora churches. This paradox raises questions about the ways that religious institutions operate in diaspora, distinct from their operations in the country of origin. This study proposes and develops the concept “institutional vernacularization” as an analytical category that facilitates assessment of how a religious institution relates to communal factors. I propose this as an alternative to secularization, which inadequately captures the diaspora dynamics. While continuing to adhere to their creeds and confessional symbols, diaspora churches shifted focus to communal agency and produced new collective and “popular” values. The community is not only a passive recipient of the spiritual gifts but is also a partner, who suggests new forms of interaction. In this sense, the diaspora church is engaged in vernacular discourse. The notion of institutional vernacularization is tested against the empirical results of field work in four Greater Toronto Area churches. -

The Rise of Bulgarian Nationalism and Russia's Influence Upon It

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2014 The rise of Bulgarian nationalism and Russia's influence upon it. Lin Wenshuang University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Wenshuang, Lin, "The rise of Bulgarian nationalism and Russia's influence upon it." (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1548. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1548 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RISE OF BULGARIAN NATIONALISM AND RUSSIA‘S INFLUENCE UPON IT by Lin Wenshuang B. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 1997 M. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2014 Copyright © 2014 by Lin Wenshuang All Rights Reserved THE RISE OF BULGARIAN NATIONALISM AND RUSSIA‘S INFLUENCE UPON IT by Lin Wenshuang B. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 1997 M. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 2002 A Dissertation Approved on April 1, 2014 By the following Dissertation Committee __________________________________ Prof. -

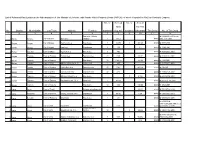

List of Released Real Estates in the Administration of the Ministry Of

List of Released Real Estates in the Administration of the Ministry of Defence, with Private Public Property Deeds (PPPDs), of which Property the MoD is Allowed to Dispose No. of Built-up No. of Area of Area the Plot No. District Municipality City/Town Address Function Buildings (sq. m.) Facilities (decares) Title Deed No. of Title Deed 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Part of the Military № 874/02.05.1997 for the 1 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Slaveykov Hospital 1 545,4 PPPD whole real estate 2 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Kapcheto Area Storehouse 6 623,73 3 29,143 PPPD № 3577/2005 3 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Sarafovo Storehouse 6 439 5,4 PPPD № 2796/2002 4 Burgas Nesebar Town of Obzor Top-Ach Area Storehouse 5 496 PPPD № 4684/26.02.2009 5 Burgas Pomorie Town of Pomorie Honyat Area Barracks area 24 9397 49,97 PPPD № 4636/12.12.2008 6 Burgas Pomorie Town of Pomorie Storehouse 18 1146,75 74,162 PPPD № 1892/2001 7 Burgas Sozopol Town of Atiya Military station, by Bl. 11 Military club 1 240 PPPD № 3778/22.11.2005 8 Burgas Sredets Town of Sredets Velikin Bair Area Barracks area 17 7912 40,124 PPPD № 3761/05 9 Burgas Sredets Town of Debelt Domuz Dere Area Barracks area 32 5785 PPPD № 4490/24.04.2008 10 Burgas Tsarevo Town of Ahtopol Mitrinkovi Kashli Area Storehouse 1 0,184 PPPD № 4469/09.04.2008 11 Burgas Tsarevo Town of Tsarevo Han Asparuh Str., Bl. -

Priority Public Investments for Wastewater Treatment and Landfill of Waste

Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Develonment Europe and Central Asia Region 32051 BULGARIA Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL SEQUENCING STRATEGIES FOR EU ACCESSION PriorityPublic Investments for Wastewater Treatment and Landfill of Waste *t~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Public Disclosure Authorized IC- - ; s - o Fk - L - -. Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized May 2004 - "Wo BULGARIA ENVIRONMENTAL SEQUENCING STRATEGIES FOR EU ACCESSION Priority Public Investments for Wastewater Treatment and Landfill of Waste May 2004 Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development Europe and Central Asia Region Report No. 27770 - BUL Thefindings, interpretationsand conclusions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. Coverphoto is kindly provided by the external communication office of the World Bank County Office in Bulgaria. The report is printed on 30% post consumer recycledpaper. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ..................................................................... i Abbreviations and Acronyms ..................................................................... ii Summary ..................................................................... iiM Introduction.iii Wastewater.iv InstitutionalIssues .xvi Recommendations........... xvii Introduction ...................................................................... 1 Part I: The Strategic Settings for -

The Splitting of the Orthodox Millet As a Secularizing Process the Clerical-Lay Assembly of the Bulgarian Exarchate (Istanbul 1871)

243 D EMETRIOS S TAMATOPOULOS / T HESSALONIKI The Splitting of the Orthodox Millet as a Secularizing Process The Clerical-Lay Assembly of the Bulgarian Exarchate (Istanbul 1871) In the fall of 1858 the first session of the Millet-i Provisional Council was convened at Fener, in the headquarters of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Istanbul; this has become known as the “Ethnosynelefsi” (“National Assembly”)1, i.e. an assembly of clerical and lay representatives of the Orthodox millet (= religious community in the Ottoman Empire) resulting from the articles of a famous imperial decree, that of the Hatt-i Hümayûn of 1856.2 The Assembly’s proceedings went on for two years, and led to the creation of a “constitutional” text, the General Regulations, which for the We should be cautious about calling the assembly of the millet’s representatives in 1858–1860 a “National Assembly” or “National” Provisional Council. The Ottoman text refers to a “commission” (komisyon), which undertook the task of formulating the Gen- eral Regulations. The term “national” became established in Greek texts of the late 19th century, when the developments described in this article as the “splitting of the millet” were re-interpreted as the “rise of the nation”, i.e., the Greek nation, within the framework of the Ottoman Empire. However, this is an anachronism and a projection of national stereotypes onto a more complex reality. For this reason, for the Assembly of 1858–1860, we will employ the term Millet-i Assembly, viz., Assembly of the Orthodox millet (al- though the great majority of representatives were Greek Orthodox, particularly after the withdrawal of two of the four Bulgarian representatives), or Patriarchate’s Assembly, in order to distinguish it from the Assembly of the Bulgarian Exarchate. -

In Bulgaria – Plovdiv

ECOLOGIA BALKANICA International Scientific Research Journal of Ecology Special Edition 2 2019 Eight International Conference of FMNS (FMNS-2019) Modern Trends in Sciences South-West University “Neofit Rilski”, Faculty of Mathematics & Natural Sciences Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria, 26-30 June, 2019 UNION OF SCIENTISTS IN BULGARIA – PLOVDIV UNIVERSITY OF PLOVDIV PUBLISHING HOUSE ii International Standard Serial Number Online ISSN 1313-9940; Print ISSN 1314-0213 (from 2009-2015) Aim & Scope „Ecologia Balkanica” is an international scientific journal, in which original research articles in various fields of Ecology are published, including ecology and conservation of microorganisms, plants, aquatic and terrestrial animals, physiological ecology, behavioural ecology, population ecology, population genetics, community ecology, plant-animal interactions, ecosystem ecology, parasitology, animal evolution, ecological monitoring and bioindication, landscape and urban ecology, conservation ecology, as well as new methodical contributions in ecology. The journal is dedicated to publish studies conducted on the Balkans and Europe. Studies conducted anywhere else in the World may be accepted only as an exception after decision of the Editorial Board and the Editor-In-Chief. Published by the Union of Scientists in Bulgaria – Plovdiv and the University of Plovdiv Publishing house – twice a year. Language: English. Peer review process All articles included in “Ecologia Balkanica” are peer reviewed. Submitted manuscripts are sent to two or three independent peer reviewers, unless they are either out of scope or below threshold for the journal. These manuscripts will generally be reviewed by experts with the aim of reaching a first decision as soon as possible. The journal uses the double anonymity standard for the peer-review process.