Playing the Game: an Exploration of the Lived Experience of Australian Elite Level Athletes, with a Focus on Their Mental Health and Wellbeing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ON the TAKE T O N Y J O E L a N D M at H E W T U R N E R

Scandals in sport AN ACCOMPANIMENT TO ON THE TAKE TONY JOEL AND MATHEW TURNER Contemporary Histories Research Group, Deakin University February 2020 he events that enveloped the Victorian Football League (VFL) generally and the Carlton Football Club especially in September 1910 were not unprecedented. Gambling was entrenched in TMelbourne’s sporting landscape and rumours about footballers “playing dead” to fix the results of certain matches had swirled around the city’s ovals, pubs, and back streets for decades. On occasion, firmer allegations had even forced authorities into conducting formal inquiries. The Carlton bribery scandal, then, was not the first or only time when footballers were interrogated by officials from either their club or governing body over corruption charges. It was the most sensational case, however, and not only because of the guilty verdicts and harsh punishments handed down. As our new book On The Take reveals in intricate detail, it was a particularly controversial episode due to such a prominent figure as Carlton’s triple premiership hero Alex “Bongo” Lang being implicated as the scandal’s chief protagonist. Indeed, there is something captivating about scandals involving professional athletes and our fascination is only amplified when champions are embroiled, and long bans are sanctioned. As a by-product of modernity’s cult of celebrity, it is not uncommon for high-profile sportspeople to find themselves exposed by unlawful, immoral, or simply ill-advised behaviour whether it be directly related to their sporting performances or instead concerning their personal lives. Most cases can be categorised as somehow relating to either sex, illegal or criminal activity, violence, various forms of cheating (with drugs/doping so prevalent it can be considered a separate category), prohibited gambling and match-fixing. -

Extract Catalogue for Auction 3

Online Auction 3 Page:1 Lot Type Grading Description Est $A FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 958 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 958 Balance of collection including 1931-71 fixtures (7); Tony Locket AFL Goalkicking Estimate A$120 Record pair of badges; football cards (20); badges (7); phonecard; fridge magnets (2); videos (2); AFL Centenary beer coasters (2); 2009 invitation to lunch of new club in Reserve A$90 Sydney, mainly Fine condition. (40+) Lot 959 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 959 Balance of collection including Kennington Football Club blazer 'Olympic Premiers Estimate A$100 1956'; c.1998-2007 calendars (21); 1966 St.Kilda folk-art display with football cards (7) & Reserve A$75 Allan Jeans signature; photos (2) & footy card. (26 items) Lot 960 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 960 Collection including 'Mobil Football Photos 1964' [40] & 'Mobil Footy Photos 1965' [38/40] Estimate A$250 in albums; VFL Park badges (15); members season tickets for VFL Park (4), AFL (4) & Reserve A$190 Melbourne (9); books/magazines (3); 'Football Record' 2013 NAB Cup. (38 items) Lot 961 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 961 Balance of collection including newspapers/ephemera with Grand Final Souvenirs for Estimate A$100 1974 (2), 1985 & 1989; stamp booklets & covers; Member's season tickets for VFL Park (6), AFL (2) & Melbourne (2); autographs (14) with Gary Ablett Sr, Paul Roos & Paul Kelly; Reserve A$75 1973-2012 bendigo programmes (8); Grand Final rain ponchos. (100 approx) Page:2 www.abacusauctions.com.au 20 - 23 November 2020 Lot 962 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 962 1921 FOURTH AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL CARNIVAL: Badge 'Australian Football Estimate A$300 Carnival/V/Perth 1921'. -

Matthew Mitcham Calls It a Day

MATTHEW MITCHAM CALLS IT A DAY Arguably Australia’s greatest ever diver, Olympic Gold Medalist Matthew Mitcham, has today announced he is retiring from the sport. 27-year-old Matthew said the time is right to hang up the togs. “I’ve had a really good run, and I’m so grateful that I’ve been able to do what I love for as long as I have,” he said. “I have achieved everything I hoped for, including the big three – Olympic Gold in 2008, World Number One in 2010, and Commonwealth Gold in 2014 – which could never have happened without all the help I’ve had along the way. “Above all, nothing has made me prouder than being able to represent my Country and my Community at the highest level of sport. The support from the public has been overwhelming, and I’m extremely grateful for that, too.” Diving Australia Chairman and two time Olympian, Michael Murphy, said Mitcham’s decision brings the curtain down on a highly successful and always entertaining career. “There’s no doubt Matthew could be regarded as our most successful diver ever,” Mr Murphy said. “He has had his fair share of ups and downs, but he has been a wonderful ambassador for our sport and an inspiration for so many athletes in general, not just divers. His gold-medal performance as a 20-year-old in Beijing, beating the highly rated Chinese divers in their own pool, is rightly considered one of Australia’s great Olympic moments.” Mr Murphy said while Mitcham’s presence will be missed on the Road in Rio, he fully understands and accepts his decision. -

Matthew Mitcham B

MATTHew MITCHAM b. March 2, 1988 OLYMPIC DIVER “Being ‘out’ for me means being just as I am with nothing to be ashamed about and no reasons to hide.” Australian diver Matthew Mitcham is one of the few openly gay Olympic athletes. At the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, Mitcham won a gold medal after executing the In Beijing, Matthew highest-scoring dive in Olympic history. Mitcham won an Olympic Mitcham grew up in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. He competed as a trampoline gold medal in the gymnast before being discovered by a diving coach. By the time he was 14, he was 10-meter platform dive. a national junior champion in diving. A few years later, he won medals in the World After his triumph, he Junior Diving Championships. leaped into the stands to In 2006, after battling anxiety and depression, Mitcham decided to retire from diving. hug and kiss his partner, The following year, he returned to diving and began training for the Olympics. Lachlan Fletcher. In Beijing, Mitcham won an Olympic gold medal in the 10-meter platform dive. It was the first time in over 80 years that an Australian male diver struck Olympic gold. After his triumph, he leaped into the stands to hug and kiss his partner, Lachlan Fletcher. Mitcham was the first out Australian to compete in the Olympics. There were only 11 openly gay athletes out of a total of over 11,000 competitors in Beijing. Mitcham was chosen 2008 Sports Performer of the Year by the Australian public. The same year, Australia GQ named him Sportsman of the Year. -

2020 Yearbook

-2020- CONTENTS 03. 12. Chair’s Message 2021 Scholarship & Mentoring Program | Tier 2 & Tier 3 04. 13. 2020 Inductees Vale 06. 14. 2020 Legend of Australian Sport Sport Australia Hall of Fame Legends 08. 15. The Don Award 2020 Sport Australia Hall of Fame Members 10. 16. 2021 Scholarship & Mentoring Program | Tier 1 Partner & Sponsors 04. 06. 08. 10. Picture credits: ASBK, Delly Carr/Swimming Australia, European Judo Union, FIBA, Getty Images, Golf Australia, Jon Hewson, Jordan Riddle Photography, Rugby Australia, OIS, OWIA Hocking, Rowing Australia, Sean Harlen, Sean McParland, SportsPics CHAIR’S MESSAGE 2020 has been a year like no other. of Australian Sport. Again, we pivoted and The bushfires and COVID-19 have been major delivered a virtual event. disrupters and I’m proud of the way our team has been able to adapt to new and challenging Our Scholarship & Mentoring Program has working conditions. expanded from five to 32 Scholarships. Six Tier 1 recipients have been aligned with a Most impressive was their ability to transition Member as their Mentor and I recognise these our Induction and Awards Program to prime inspirational partnerships. Ten Tier 2 recipients time, free-to-air television. The 2020 SAHOF and 16 Tier 3 recipients make this program one Program aired nationally on 7mate reaching of the finest in the land. over 136,000 viewers. Although we could not celebrate in person, the Seven Network The Melbourne Cricket Club is to be assembled a treasure trove of Australian congratulated on the award-winning Australian sporting greatness. Sports Museum. Our new SAHOF exhibition is outstanding and I encourage all Members and There is no greater roll call of Australian sport Australian sports fans to make sure they visit stars than the Sport Australia Hall of Fame. -

Homosexuality and the Olympic Movement*

Homosexuality and the Olympic Movement* By Matthew Baniak and Ian Jobling Sport remains “one of the last bastions of cultural and the inception of the modern Games until today. An Matthew Baniak institutional homophobia” in Western societies, despite examination of key historical events that shaped the was an Exchange Student from the University of Saskatchewan, the advances made since the birth of the gay rights gay rights movement helps determine the effect homo- Canada at the University of movement.1 In a heteronormative culture such as sport, sexuality has had on the Olympic Movement. Through Queensland, Australia in 2013. Email address: mob802@mail. lack of knowledge and understanding has led to homo- such scrutiny, one may see that the Movement has usask.ca phobia and discrimination against openly gay athletes. changed since the inaugural modern Olympic Games The Olympic Games are no exception to this stigma. The in 1896. With the momentum of news surrounding the Ian Jobling goal of the Olympic Movement is to 2014 Sochi Games and the anti-gay laws in Russia, this is Director, Centre of Olympic … contribute to building a peaceful and better world issue of homosexuality and the Olympic Movement Studies and Honorary Associate by educating youth through sport united with art has never been so significant. Sections of this article Professor, School of Human Movement Studies, University of and culture practiced without discrimination of any will outline the effect homosexuality has had on the Queensland. Email address: kind and in the -

Nswis Annual Report 2010/2011

nswis annual report 2010/2011 NSWIS Annual Report For further information on the NSWIS visit www.nswis.com.au NSWIS a GEOFF HUEGILL b NSWIS For further information on the NSWIS visit www.nswis.com.au nswis annual report 2010/2011 CONtENtS Minister’s Letter ............................................................................... 2 » Bowls ...................................................................................................................41 Canoe Slalom ......................................................................................................42 Chairman’s Message ..................................................................... 3 » » Canoe Sprint .......................................................................................................43 CEO’s Message ................................................................................... 4 » Diving ................................................................................................................. 44 Principal Partner’s Report ......................................................... 5 » Equestrian ...........................................................................................................45 » Golf ......................................................................................................................46 Board Profiles ..................................................................................... 6 » Men’s Artistic Gymnastics .................................................................................47 -

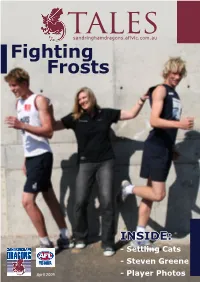

Fighting Frosts a Glance at the Frost Family and Their Sporting Ambitions 31 Afl Player Profile Ted Richards on His Life As a Swan and Little Brother Xavier

TALES sandringhamdragons.aflvic.com.au F i g h t i n g Frosts INSIDE:INSIDE: - Settling Cats - Steven Greene April 2009 - Player Photos proudly supported by: website: sandringhamdragons.aflvic.com.au location: D.C. Bricker Pavilion, Princes Park, Caulfield South 3162. mail: PO Box 101 Caulfield South 3162. email: [email protected] phone: 03 9532 8688 fax: 9532 9034 advertising: [email protected] managing editor: Tikali Nicholls. Brand Identity Guidlines editorial contributors: Darryl Hunt, Jonno Nash, Tikali Nicholls. photographic contributors: Darryl Hunt, Jennifer Stenglein,Tikali Nicholls, Ian Penn. printer: Australian Supplies and Printing special thanks to: those who contributed their time to this edition. front cover: Wendy Frost and sons Sam and Jack. Sandringham Dragons For all your design & print 9555 9798 2 - DRAGON TALES - sandringhamdragons.aflvic.com.au Creating champions on the field and safer drivers on the road. 4 - DRAGON TALES - sandringhamdragons.aflvic.com.au sandringhamdragons.aflvic.com.au - DRAGONTALES - 5 8 10 24 contents 16 04 under 16 academy summer photos of those who joined the dragons in preparation for the metro carnival 08 around the dragons a catch up on the news in the region 22 TAC under 18 training squad photos of many young promising footballers who joined new senior coach dale tapping and his team in the pursuit for a TAC team jumper 16 cover story: fighting frosts a glance at the frost family and their sporting ambitions 31 afl player profile ted richards on his life as a swan and little -

Darren Glass

Darren Glass Former captain West Coast Eagles, leadership speaker Darren Glass is a former Australian Rules footballer who was one of the West Coast Eagles all-time great players and was highly regarded for his leadership abilities during his playing career. He was a champion defender for the Eagles and played 270 games for the club during his 14-year career. Today, Darren is highly sought after and highly respected as a leadership speaker at corporate, government and sporting events. Originally from Western Australia, Darren began his career with Perth Football Club in the West Australian Football League (WAFL), before being recruited by West Coast Eagles with the 11th pick in the 1999 National Draft. He made his debut for the Club the following season in Round 4, 2000 against Adelaide. Playing mainly as a full back, Darren was named in the All-Australian team on four occasions (2006, 2007, 2011), and as Captain of the 2012 team. During his extensive career with the Eagles he played in a team of well-known stars including Chris Judd, Daniel Kerr and Ben Cousins. On 9 November 2007 Darren was announced as the new Captain of West Coast Eagles following the departure of Chris Judd who returned to Victoria. Darren was appointed to lead the recovery of the club after a series of off-field scandals. Darren was captain of West Coast Eagles for 129 matches and is widely acknowledged as an outstanding leader – with only his former coach, John Worsfold (138 games), leading the club into battle more often. After a successful season playing all 22 matches in 2009, Darren won his second Club Champion Award ahead of fellow defender Shannon Hurn. -

Vznik a Vývoj Vybraných Plaveckých Sportů V Rámci Novodobých Olympijských Her

Z A V PLZNI FAKULTA PEDAGOGICKÁ ÁPADOČESKÁ UNIVERZIT CENTRUM TĚLESNÉ VÝCHOVY A SPORTU Vznik a vývoj vybraných plaveckých sportů v rámci novodobých olympijských her DIPLOMOVÁ PRÁCE Bc. Lenka Metličková Učitelství pro 2. stupeň ZŠ, obor Tv-Te Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Radek Zeman Plzeň 2021 s Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně použitím uvedené literatury a zdrojů informací. , 19.dubna 2021 Plzeň ………………………………………….. vlastnoruční podpis PODĚKOVÁNÍ CHTĚLA BYCH TÍMTO PODĚKOVAT VEDOUCÍMU MÉ DIPLOMOVÉ PRÁCE MGR. RADKOVI ZEMANOVI Z PEDAGOGICKÉ FAKULTY ZÁPADOČESKÉ UNIVERZITY V PLZNI ZA ODBORNÉ VEDENÍ A CENNÉ PŘIPOMÍNKY PŘI JEJÍM VYPRACOVÁNÍ. 1 OBSAH 2 ÚVOD....................................................................................................................................... 6 3 CÍL A ÚKOLY PRÁCE................................................................................................................... 7 3.1 CÍL PRÁCE ......................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 ÚKOLY PRÁCE ................................................................................................................... 7 3.3 METODIKA PRÁCE ............................................................................................................. 7 4 HISTORIE OLYMPISMU ............................................................................................................. 8 4.1 HISTORIE OH V ANTICE .................................................................................................... -

AFL Vic Record Week 23.Indd

VFL Round 19 TAC Cup Round 17 21 - 23 August 2015 $3.00 Tips to avoid BetRegret Gamble less than once a week Leave your debit and credit cards at home Take breaks when gambling Don’t let it lead to something bigger. Get all the tips at betregret.com.au Authorised by the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, Melbourne. Photo: Dave Savell Features 4 5 Nick Carnell 7 Alan Hales / Peter Henderson 9 Gary Ayres Every week Editorial 3 VFL Highlights 10 VFL News 11 TAC Cup Highlights 14 TAC Cup News 15 AFL Vic News 16 Club Whiteboard 18 21 Events 23 Get Social 24 25 Draft Watch 64 Who’s playing who 34 35 Essendon vs Footscray 52 53 North Ballarat vs Calder 36 37 Collingwood vs Richmond 54 55 Oakleigh vs Geelong 38 39 Coburg vs Casey Scorpions 56 57 Bendigo vs Northern 40 41 Northern Blues vs Box Hill Hawks 58 59 Gippsland vs Sandringham 42 43 Port Melbourne vs Frankston 60 61 Western vs Dandenong 44 45 Williamstown vs Werribee 62 63 Murray vs Eastern 46 47 Sandringham vs Geelong Editor: Ben Pollard ben.pollard@afl vic.com.au Contributors: Anthony Stanguts Design & Print: Cyan Press Photos: AFL Photos (unless otherwise credited) Ikon Park, Gate 3, Royal Parade, Carlton Nth, VIC 3054 Advertising: Ryan Webb (03) 8341 6062 GPO Box 4337, Melbourne, VIC 3001 Phone: (03) 8341 6000 | Fax: (03) 9380 1076 AFL Victoria CEO: Steven Reaper www.afl vic.com.au State League & Talent Manager: John Hook High Performance Managers: Anton Grbac, Leon Harris Cover: Dion Hill in action for Coburg during the Lions’ Talent Operations Coordinator: Rhy Gieschen Round -

2008 AFL Annual Report

PRINCIPLES & OUTCOMES MANAGING THE AFL COMPETITION Principles: To administer our game to ensure it remains the most exciting in Australian sport; to build a stronger relationship with our supporters by providing the best sports entertainment experience; to provide the best facilities; to continue to expand the national footprint. Outcomes in 2008 ■■ Attendance record for Toyota AFL ■■The national Fox Sports audience per game Premiership Season of 6,511,255 compared was 168,808, an increase of 3.3 per cent to previous record of 6,475,521 set in 2007. on the 2007 average per game of 163,460. ■■Total attendances of 7,426,306 across NAB ■■The Seven Network’s broadcast of the 2008 regional challenge matches, NAB Cup, Toyota AFL Grand Final had an average Toyota AFL Premiership Season and Toyota national audience of 3.247 million people AFL Finals Series matches was also a record, and was the second most-watched TV beating the previous mark of 7,402,846 set program of any kind behind the opening in 2007. ceremony of the Beijing Olympics. ■■ For the eighth successive year, AFL clubs set a ■■ AFL radio audiences increased by five membership record of 574,091 compared to per cent in 2008. An average of 1.3 million 532,697 in 2007, an increase of eight per cent. people listened to AFL matches on radio in the five mainland capital cities each week ■■The largest increases were by North Melbourne (up 45.8 per cent), Hawthorn of the Toyota AFL Premiership Season. (33.4 per cent), Essendon (28 per cent) ■■The AFL/Telstra network maintained its and Geelong (22.1 per cent).