Development Process of Geotourism in the Kanawinka Region in the Context of the Australian Geopark Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Main History

The chronology of Bowls 1844 – First green laid at Mr. Lipscombe’s Beach Tavern at Sandy Bay Tasmania – Bowling Green Hotel Sandy Bay Tasmania 1845 – First recorded game of bowls at the back of the Beach Tavern (Sandy Bay, TAS). 1846 – First bowling club in Australia is established alongside the Bowling Green Hotel in Sandy Bay. (TAS) – This club was closed in 1853. 1848 - Aberdeen Sports and Recreation Club (NSW) 1852 – 1000 spectators paid to watch a match at the Bowling Green Hotel green between civilians and the military. 1864 – Melbourne Bowls Club is formed (oldest existing bowling club in Australia)(Vic) . – First bowls made in Australia, turned by Mr Alcock, Russell Street, Melbourne. – Ballarat Bowling Club (Vic) – Fitzroy (North Fitzroy) Bowling Club (Vic) 1865 – St Kilda Sporting Club (formerly St Kilda Bowling Club) (Vic) – City of Melbourne Bowling Club (Vic) – Fitzroy (North Fitzroy) Bowling Club (Vic) 1866 – City of Melbourne Bowling Club (Vic) 1868 – Carlton Bowling Club (Vic) – Learmonth Bowling Club (Vic) – Richmond Union Bowling Club (Vic) 1872 – George S. Coppin entrepreneur, suggested first bowling carnival in Australia. This was not taken up. – Buninyong Bowls Club Inc (Vic) – Cambridge College Club – (Private Club) 1873 – Albert Park Bowls Club Inc -(Formerly -South Melbourne Bowling Club (1873-1929), Albert Park Bowling Club (1929- 1942), Albert Park VRI Bowls Club (1942-2011) – Creswick Bowling Club (Vic) 1876 – First game of bowls in SA on green put down by Andrew Thomson at Kapund – Kyneton Bowling Club (Vic) -

Mount Schank Mt Schank

South West Victoria & South East South Australia Craters and Limestone MT GAMBIER Precinct: Mount Schank Mt Schank PORT MacDONNELL How to get there? Mount Schank is 10 minutes south of Mount Gambier along the Riddoch Highway. Things to do: • Two steep walking trails offer a great geological experience. The Mount Schank is a highly prominent volcanic cone Viewing Platform Hike (900m return) begins at the car park located 10 minutes south of Mount Gambier, which and goes to the crater rim. From protrudes above the limestone plain, providing the top, overlooking the nearby panoramic views. quarry, evidence can be seen of the lava flow and changes in the Early explorer Lieutenant James Grant named this fascinating remnant rock formation caused by heat volcano after a friend of his called Captain Schank. and steam. On the southern side The mountain differs from the craters in Mount Gambier in that its of the mountain, a small cone can floor is dry, being approximately at the level of the surrounding plain. be seen which is believed to have been formed by the first of two Evidence suggests two phases of volcanic activity. A small cone on the main stages. southern side of the mount was produced by the early phase, together with a basaltic lava flow to the west (the site of current quarrying • The Crater Floor Walk (1.3km operations). The later phase created the main cone, which now slightly return) also begins in the car park, overlaps the original smaller one and is known as a hybrid maar-cone and winds down to the crater floor structure. -

SCG Victorian Councils Post Amalgamation

Analysis of Victorian Councils Post Amalgamation September 2019 spence-consulting.com Spence Consulting 2 Analysis of Victorian Councils Post Amalgamation Analysis by Gavin Mahoney, September 2019 It’s been over 20 years since the historic Victorian Council amalgamations that saw the sacking of 1600 elected Councillors, the elimination of 210 Councils and the creation of 78 new Councils through an amalgamation process with each new entity being governed by State appointed Commissioners. The Borough of Queenscliffe went through the process unchanged and the Rural City of Benalla and the Shire of Mansfield after initially being amalgamated into the Shire of Delatite came into existence in 2002. A new City of Sunbury was proposed to be created from part of the City of Hume after the 2016 Council elections, but this was abandoned by the Victorian Government in October 2015. The amalgamation process and in particular the sacking of a democratically elected Council was referred to by some as revolutionary whilst regarded as a massacre by others. On the sacking of the Melbourne City Council, Cr Tim Costello, Mayor of St Kilda in 1993 said “ I personally think it’s a drastic and savage thing to sack a democratically elected Council. Before any such move is undertaken, there should be questions asked of what the real point of sacking them is”. Whilst Cr Liana Thompson Mayor of Port Melbourne at the time logically observed that “As an immutable principle, local government should be democratic like other forms of government and, therefore the State Government should not be able to dismiss any local Council without a ratepayers’ referendum. -

Dundas Tableland Precinct

South West Victoria & South East South Australia Dundas Tableland Nigretta Falls Precinct: Wannon Falls Nigretta Falls HAMILTON Nigretta Falls 410 million year Wannon River old volcanic rock Complex crack patterns in the hard rock control the form of the falls - producing a series of cascades. How to get there? Nigretta Falls is a small waterfall set in outstanding scenery. The turn-off to the falls is signposted The waterfall is considered more spectacular than Wannon Falls, off Nigretta Road, 5 kilometres west of due to its clearer features. Hamilton along the Glenelg Highway. The history surrounding the Wannon and Nigretta Falls dates back to the 1850’s when the small town of Redruth, renamed Wannon in 1908, was first settled. Things to do: Planned around the Wannon Inn and a ferry for crossing the river, the community • A walk to Nigretta Falls commences consisted of two schools, two hotels, a store and four sawmills located nearby. approximately five kilometres off Over time, the Falls became a popular tourist attraction, attracting many visitors in the Hamilton to Mount Gambier the 1890s when excursion trains travelled from Hamilton. Road and is well signposted. It is The Hamilton Progress Association developed in 1908 tried to establish Nigretta possible to walk both to the base Falls as a picnic resort, but was not successful in establishing a reserve until 1912. and headwaters of the falls. Working bees were then organized to clean up the area, plant trees and improve facilities for visitors. • The area has excellent river walks Formation of the Nigretta Falls: The Nigretta Falls are also developed on a hard and viewing areas with barbecue rock outcrop, but these have no underlying soft bed to allow easy undermining facilities and red gum picnic tables. -

Government Emblems, Embodied Discourse and Ideology: an Artefact-Led History of Governance in Victoria, Australia

Government Emblems, Embodied Discourse and Ideology: An Artefact-led History of Governance in Victoria, Australia Katherine Hepworth Doctor of Philosophy 2012 ii iii Abstract Government emblems are a rich source of historical information. This thesis examines the evidence of past governance discourses embodied in government emblems. Embodied discourses are found within an archive of 282 emblems used by local governments in Victoria, Australia in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. They form the basis of a history of governance in the State of Victoria from first British exploration in 1803 to the present day. This history of governance was written to test the main contribution of this thesis: a new graphic design history method called discursive method. This new method facilitates collecting an archive of artefacts, identifying discourses embodied within those artefacts, and forming a historical narrative of broader societal discourses and ideologies surrounding their use. A strength of discursive method, relative to other design history methods, is that it allows the historian to seriously investigate how artefacts relate to the power networks in which they are enmeshed. Discursive method can theoretically be applied to any artefacts, although government emblems were chosen for this study precisely because they are difficult to study, and rarely studied, within existing methodological frameworks. This thesis demonstrates that even the least glamorous of graphic design history artefacts can be the source of compelling historical narratives. iv Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been written without the support of many people. Fellow students, other friends and extended family have helped in many small ways for which I am so grateful. -

Mount Napier State Park Byaduk Caves Mount Harmans Valley Rouse and Byaduk Caves Tumuli BYADUK

South West Victoria & South East South Australia HAMILTON Lava Flows Precinct BRANXHOLME PENSHURST Mt Napier State Park Mount Napier State Park Byaduk Caves Mount Harmans Valley Rouse and Byaduk Caves Tumuli BYADUK MACARTHUR How to get there? Access to Mount Napier State Park is from the Hamilton to Port Fairy Road. Turn into Murroa Lane to Coles Track, and then turn left into Menzel’s Pit Road to reach the start of the summit walk. Things to do: • The Byaduk Caves are situated in the Harman’s Valley lava flow. They are accessed through collapsed roof sections and display many well-preserved features left by the retreating and cooling lava. The largest tunnels are up to 18 metres wide, 10 metres high, and extend to depths of 20 metres below the surface. • The Byaduk Caves provide many opportunities for nature The Byaduk Caves in Mount Napier State Park are a very extensive and study and walking, and a well signposted loop begins at accessible set of lava caves. Being so young (only 8,000 years), they are the end of the gravel road. largely unweathered and still maintain their natural state. • Lava tubes, sinkholes and unique flora and fauna can be observed from the many viewing points situated on the The caves were formed when a spectacular lava fountain several hundred metres high roared cave edges of Harman’s Caves 1 and 2 and Bridge cave. up from a lava lake in Mt Napier’s crater. The lava rose from a depth of over 30 kilometres and (The walking track starts and ends at the car park.) its temperature was about 1200 degrees Celsius. -

Download (PDF)

Panel Discussion PDV Protected Volcanic Areas and Volcanological Heritage (IAVCEI, UNESCO, IUGS) A contribution by Bernard Joyce University of Melbourne Australia Geoheritage and Geotourism in the Protected Volcanic Area of the Kanawinka Geopark: part of the monogenetic Newer Volcanic Province of SE Australia. Bernard Joyce University of Melbourne Australia Founder Member of the new Standing Committee for Geotourism of the Geological Society of Australia UNESCO and volcanic heritage: there are many new volcanic Geoparks around the world, often inhabited areas such as the Kanawinka Geopark of southeastern Australia. How can we work with indigenous and other local inhabitants in managing such natural sites? 3 Kanawinka Geopark application to UNESCO in December 2006 Aboriginal stone hut - Mt Napier flows 7 8 9 On the new National Heritage Register 10 Budj Bim, Western Victoria – a bid for World Heritage GLOBAL GEOPARKS What is a Geopark? A territory with well-defined limits that has a large enough surface area for it to serve local economic development. That comprises a certain number of geological heritage sites (on any scale) or a mosaic of geological entities of special scientific importance, rarity or beauty, representative of an area and its geological history, events or processes. It may not solely be of geological significance but also of archaeological, ecological, historical or cultural value. Newer Volcanic Province of SE Australia Explorer Mitchell’s 1836 field view Newer Volcanic Province of SE Australia Eugène von Guérard Larra 1857 Eugène von Guérard Mt Elephant 1857 Mt Napier lava shield, scoria cones, valley flow & signboard Mt Napier as seen by Mitchell in 1836 Gnotuk maar (von Guerard 1857) Eugène von Guérard Lake Bullen Merri 1858 These cultural features, supported by a detailed geological and geomorphological story, have helped make the area an ideal candidate for nomination as a Geopark. -

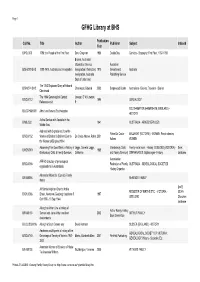

GFHG Library at BHS

Page 1 GFHG Library at BHS Publication Call No. Title Author Publisher Subject Indexed Year B/POL/070 1788: the People of the First Fleet Don, Chapman 1986 DoubleDay Convicts - Biography; First Fleet, 1787-1788 Branch, Australian Information Service Australian B/SHI/080 BHS 1788-1975, Australia and Immigration Immigration Information; 1975 Government Australia Immigration, Australia Publishing Service Dept of Labor and The 1863 Shipboard Diary of Edward B/SHI/074 BHS Charlwood, Edward 2003 Burgewood Books Australians - Diaries; Travelers - Diaries Charlwood The 1994 Genealogical Contact Lawson, D W; Lawson, B/SOU/112 1994 GENEALOGY Reference vol 1 P SOUTHAMPTON (HAMPSHIRE, ENGLAND) - B/LOC/HAM/001 About and Around Southampton HISTORY Active Service with Australia in the B/MIL/032 1941 AUSTRALIA - ARMED SERVICES Middle East Address (with Signatories) from the Robin Da Costa- BALLARAT (VICTORIA) - WOMEN; Penal colonies; B/SOU/152 Women of Ballarat & Ballarat East to Da Costa-Adams, Robin 2001 Adams WOMEN the Women of England 1864 Advancing This Good Work: a history of Jaggs, Donella; Jaggs, Glastonbury Child Family social work - History; GEELONG (VICTORIA) - Book B/HOS/019 1988 Glastonbury Child & Family Services Catherine and Family Services] ORPHANAGES; Orphanages - History database Australasian AFFHO directory of genealogical B/SOU/058 Federation of Family AUSTRALIA - GENEALOGICAL SOCIETIES organisations in Australasia History Organisa Alexander Mckenzie (Convict) Family B/FAM/056 McKENZIE FAMILY Notes [part] All Saints Anglican Church, -

Corangamite Salinity Action Plan 2003

Corangamite CMA Salinity Action Plan. Background Report No.4. Asset manager consultation, preferred methods of implementation and management actions Authored by: Cam Nicholson 1, Graeme Anderson 2 & Mike Stephens 3 1Nicon Rural Services, Queenscliff 2Department of Primary Industries, Geelong 3Mike Stephens & Associates Pty Ltd, Yendon Corangamite Catchment Management Authority, 2003 Published by the Corangamite Catchment Management Authority, 2003 64 Dennis Street Colac Victoria 3250 Website: http://www.ccma.vic.gov.au The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: ISBN ISSN Cover photo: Untreated saline land, Meredith area. Photograph: Graeme Anderson This document has been prepared for use by the Corangamite Catchment Management Authority by Mike Stephens & Associates Pty Ltd and has been compiled by using the consultants’ expert knowledge, due care and professional expertise. The Corangamite Catchment Management Authority, Mike Stephens & Associates Pty Ltd and other contributors do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for every purpose for which it may be used and therefore disclaim all liability for any error, loss, damage or other consequence whatsoever which may arise from the use of or reliance on the information contained in this publication. Corangamite Salinity Action Plan 2003 Project team: Mike Stephens, Mike Stephens & Associates Pty Ltd Cam Nicholson, Nicon Rural Services Pty Ltd Peter Dahlhaus, Dahlhaus Environmental Geology Pty Ltd Graeme Anderson, Department of Primary Industries Roger Standen, Rendell McGuckian Pty Ltd Karlie Tucker, Rendell McGuckian Pty Ltd Project management Tim Corlett, Corangamite CMA Mike Stephens & Associates and Dahlhaus Environmental Geology Pty Ltd i Corangamite CMA Salinity Action Plan. -

Urban Renewal

VICTORIA 197 4-75 TOWN & COUNTRY PLANNING BOARD OF VICTORIA THIRTIETH ANNUAL REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 1974-1975 PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION S (2) OF THE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1961 By Authority: No. 79.-11166/75.-PRICB $1.00 C. H. RIXON, GOVERNMENT PRINTER. MELBOURNE. Contents 5 The year in review 7 Legislation 8 Delegation of the Board's powers and functions 9 State Planning Council 12 AlburyjWodonga 14 Melton and Sunbury 18 Urban renewal 20 Strategic planning 20 Investigation and designated area studies 21 Regional planning 23 Co-operative activities with Commonwealth Government agencies 24 Statements of planning policy 26 Other studies 27 Statutory planning 27 Planning schemes being prepared by the Board 30 Planning schemes approved 31 Melbourne Metropolitan planning area 32 Interim development orders 32 Permits 32 Revocations 33 Committees 36 Promotion of planning 38 Planning and Privacy 42 Board members and staff 43 Appendices THIRTIETH ANNUAL REPORT 235 Queen Street, Melbourne, 3000 The Honorable the Minister for Planning, 480 Collins Street, Melbourne, 3000. Sir, In accordance with the prov1s1ons of Section 5 (2) of the Town and Country Planning Act 1961, the Board has pleasure in submitting to you for presentation to Parliament the following report on its activities during the twelve months ended 30th June, 1975. The Year in Review This has been yet another important year for planning in Victoria. New concepts introduced last year changed the scope and direction of planning considerably involving the Board in a greater range of activities. The recent involvement of the Commonwealth Government in urban and regional planning has continued. -

Lava Flows Precinct DUNKELD HAMILTON Mount Rouse

South West Victoria & South East South Australia Lava Flows Precinct DUNKELD HAMILTON Mount Rouse PENSHURST Mt Rouse How to get there? Mount Rouse is located two kilometres south of the township of Penshurst on the Hamilton Highway and is well signposted. Things to do: • A wide, grassy track meanders down to the dry crater lake. You can also Twenty minutes east of Hamilton lies the town of climb the steps to the summit for fantastic views of a large proportion Penshurst, which is home to the extinct volcano Mount of the Western District Volcanic Rouse. The mountain is a massive accumulation of Plains. scoria, rising 100 metres above the surrounding volcanic • Picnic tables and toilets are located plain. Its high relief offers an important vantage point at the second car park, along with an from which to view the lavas and adjacent volcanoes of interesting additional short walk. Mount Eccles and Mount Napier. • Visit Penshurst Volcanoes Discovery Centre at 23 Martin Street, Open Mount Rouse is built mainly of red and brown scoria with thin, Friday to Sunday 10am - 4pm interbedded basalt lava flows. The scoria forms an arcuate mound or by appointment by phoning opening towards the south-west, giving the appearance of a (03) 5576 7233 breached cone. To the south of the main scoria cone is a deep circular crater with a small lake and a smaller shallow crater rimmed with basalt. Past lava flows from Mount Rouse followed shallow, gently sloping river courses, extending at least 60 kilometres south. A thin basalt lava flow contained in the scoria cone has been dated at approximately 1.8 million years old. -

November 2014, Volume 44, No 5

Published November 2014, Volume 44, No 5. Inc. No. A00245412U President Robert Missen: 03 52346351 Email: [email protected] Secretary Jen McDonald: 03 52321296 Email: [email protected] Postal Address: PO Box 154 Colac 3250 Email: [email protected] Newsletter Editor: Ellise Angel: 03 52338280 Email: [email protected] Treasurer Liz Chambers: 03 52314572 Annual Membership fee: $20.00 per person – due in May Historical Society Meetings are held monthly on the 4th Wednesday at 7.30pm, except in January, and during winter on the 4th Saturday at 1.30pm. Open Hours for the public at COPACC History Centre: Thursday, Friday and Sunday 2.00pm to 4.00pm Working Bees at the History Centre are on the 1st & 3rd Wednesdays 10.00 am - 12.00 noon Dates for your Diary Wednesday Nov 26th 7.30pm Meeting & Members’ Night- bring an item to show. Wednesday December 10th CHRISTMAS BREAK- UP 6.00pm at the History Centre. Meat platters, pudding and punch provided, please bring a salad, side dish, sweet or nibbles to share. We need to know numbers attending so contact Liz and pay at Nov meeting- $12 thankyou. There will be good food, good company, carol singing with Dawn M and Christmas Trivia with John A. Wednesday February 25th 2015 Commencement BBQ meeting- venue to be advised. Forthcoming Meetings in addition to CDHS activities: Colac P & A Society Heritage Festival – Saturday January 31 & Sunday February 1 at Colac Showgrounds – a Joint Display with Colac & District Family History Group. Joint Meeting with Family History Group – Wednesday February 4 at 7.30pm.