Burundi Refugee Rights at Risk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Situation Report #2, Fiscal Year (FY) 2003 March 25, 2003 Note: the Last Situation Report Was Dated November 18, 2002

U.S. AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT BUREAU FOR DEMOCRACY, CONFLICT, AND HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE (DCHA) OFFICE OF U.S. FOREIGN DISASTER ASSISTANCE (OFDA) BURUNDI – Complex Emergency Situation Report #2, Fiscal Year (FY) 2003 March 25, 2003 Note: The last situation report was dated November 18, 2002. BACKGROUND The Tutsi minority, which represents 14 percent of Burundi’s 6.85 million people, has dominated the country politically, militarily, and economically since national independence in 1962. Approximately 85 percent of Burundi’s population is Hutu, and approximately one percent is Twa (Batwa). The current cycle of violence began in October 1993 when members within the Tutsi-dominated army assassinated the first freely elected President, Melchoir Ndadaye (Hutu), sparking Hutu-Tutsi fighting. Ndadaye’s successor, Cyprien Ntariyama (Hutu), was killed in a plane crash on April 6, 1994, alongside Rwandan President Habyarimana. Sylvestre Ntibantunganya (Hutu) took power and served as President until July 1996, when a military coup d’etat brought current President Pierre Buyoya (Tutsi) to power. Since 1993, an estimated 300,000 Burundians have been killed. In August 2000, nineteen Burundian political parties signed the Peace and Reconciliation Agreement in Arusha, Tanzania, overseen by peace process facilitator, former South African President Nelson Mandela. The Arusha Peace Accords include provisions for an ethnically balanced army and legislature, and for democratic elections to take place after three years of transitional government. The three-year transition period began on November 1, 2001. President Pierre Buyoya is serving as president for the first 18 months of the transition period, to be followed in May 2003 by a Hutu president for the final 18 months. -

Burundi-SCD-Final-06212018.Pdf

Document of The World Bank Report No. 122549-BI Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF BURUNDI ADDRESSING FRAGILITY AND DEMOGRAPHIC CHALLENGES TO REDUCE POVERTY AND BOOST SUSTAINABLE GROWTH Public Disclosure Authorized SYSTEMATIC COUNTRY DIAGNOSTIC June 15, 2018 Public Disclosure Authorized International Development Association Country Department AFCW3 Africa Region International Finance Corporation (IFC) Sub-Saharan Africa Department Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) Sub-Saharan Africa Department Public Disclosure Authorized BURUNDI - GOVERNMENT FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective as of December 2016) Currency Unit = Burundi Franc (BIF) US$1.00 = BIF 1,677 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ACLED Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project AfDB African Development Bank BMM Burundi Musangati Mining CE Cereal Equivalent CFSVA Comprehensive Food Security and Vulnerability Assessment CNDD-FDD Conseil National Pour la Défense de la Démocratie-Forces pour la Défense de la Démocratie (National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy) CPI Consumer Price Index CPIA Country Policy and Institutional Assessment DHS Demographic and Health Survey EAC East African Community ECVMB Enquête sur les Conditions de Vie des Menages au Burundi (Survey on Household Living Conditions in Burundi) ENAB Enquête Nationale Agricole du Burundi (National Agricultural Survey of Burundi) FCS Fragile and conflict-affected situations FDI Foreign Direct Investment FNL Forces Nationales -

Burundi CERF Narrative Report 2008.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE HUMANITARIAN/RESIDENT COORDINATOR ON THE USE OF CERF GRANTS Country Burundi Humanitarian / Resident Youssef Mahmoud Coordinator Reporting Period 1 January – 31 December 2008 I. Executive Summary Two allocations were granted to Burundi in 2008: one from the rapid response window ($1.6 million) and one from the underfunded window ($3.6 million). In both cases and in absence of a Consolidated Humanitarian Appeal for the first time in seven years, CERF funding provided much needed emergency support to tackle both the food crisis and underfunded emergencies in a context of transition and fragile recovery. The initial rapid response allocation came at a critical time for Burundi, one of the countries hardest hit by the soaring food prices with an increase of more than 130 percent between 2007 and 2008. It enabled strengthening the health and nutrition response to needs of 1,100 new severe acute malnourished children and the extension of screening programs for 16,000 children. The purchase of seeds and tools for 40,000 families recently returned from Tanzania prevented a large number of repatriated refugees from falling into the cycle of severe food insecurity. The underfunded grant enabled meeting critical food needs for 15,000 Burundian refugees from 1972 who were repatriated in 2008. This group was initially not included in the planning of UN agencies as their return started when both Burundian and Tanzanian Governments reached an agreement on the naturalization process of those willing to remain in Tanzania. The same grant provided a much needed food return package for Burundians expelled from Tanzania. -

World Vision Burundi Annual Report

World Vision Burundi 2010 – 2011 Annual Report ------------------------------------------------------- World Vision Burundi 2010 - 2011 ------------------------------------------------------ - 1 - Our vision for every child, life in all its fullness; Our prayer for every heart, the will to make it so. Who we are World Vision is a Christian humanitarian organization dedicated to working with children, families, and their communities worldwide to reach their full potential by tackling the causes of poverty and injustice. We serve close to 100 million people in nearly 100 countries around the world. Motivated by our faith in Jesus Christ, we serve alongside the poor and oppressed as a demonstration of God’s unconditional love for all people – regardless of religion, race, ethnicity or gender. Mission statement World Vision is an international partnership of Christians whose mission is to follow our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ in working with the poor and oppressed to promote human transformation, seek justice, and bear witness to the good news of the Kingdom of God. We pursue this mission through integrated, holistic commitment to: • Transformational Development that is community-based and sustainable, focused especially on the needs of children: • Emergency Relief that assist people affected by conflict or natural disaster; • Promotion of Justice that seeks to change unjust structures affecting the poor among whom we work; • Partnership with Churches to contribute to spiritual and social transformation; • Public Awareness that leads to informed understanding, giving, involvement and prayer; • Witness to Jesus Christ by life, deed word and sign that encourages people to respond to the Gospel. Inspired by our Christian values, we are dedicated to working with the world’s most vulnerable people. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MAP OF BURUNDI I INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 II THE DEVELOPMENT OF REGROUPMENT CAMPS ...................................... 2 III OTHER CAMPS FOR DISPLACED POPULATIONS ........................................ 4 IV HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS DURING REGROUPMENT ......................... 6 Extrajudicial executions ......................................................................................... 6 Property destruction ............................................................................................... 8 Possible prisoners of conscience............................................................................ 8 V HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN THE CAMPS ........................................... 8 Undue restrictions on freedom of movement ......................................................... 8 "Disappearances" ................................................................................................... 9 Life-threatening conditions .................................................................................. 10 Insecurity in the context of armed conflict .......................................................... 11 VI HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS DISGUISED AS PROTECTION ................ 12 VII CONCLUSION.................................................................................................... 14 VIII RECOMMENDATIONS ..................................................................................... 15 -

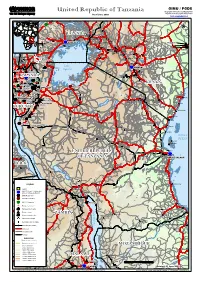

United Republic of Tanzania Geographic Information and Mapping Unit Population and Geographic Data Section As of June 2003 Email : [email protected]

GIMU / PGDS United Republic of Tanzania Geographic Information and Mapping Unit Population and Geographic Data Section As of June 2003 Email : [email protected] Soroti Masindi ))) ))) Bunia ))) HoimaHoima CCCCC CCOpiOpi !!! !! !!! !! !!! !! Mbale 55 !! 5555 55 Kitale !! 5555 Fort Portal UGANDAUGANDA !! CC !! Tororo !! ))) ))) !! ))) Bungoma !! !! Jinja CCCCCSwesweSweswe ))) Isiolo Tanzania_Atlas_A3PC.WOR CC ))) CC ))) KAMPALAKAMPALA ))) Kakamega DagahaleyDagahaley ))) Butembo !! ))) !! Entebbe Kisumu ))) Thomsons Falls!! Nanyuki IfoIfoIfo KakoniKakoni ))) !! ))) ))) ))) HagaderaHagadera ))) Lubero Londiani ))) DadaabDadaab Kabatoro ))) Molo ))) !! Nakuru ))) Bingi Elburgon !! Nyeri Gilgil ))) !! Embu CC))) MbararaMbarara Kinyasano CCMbararaMbarara !! Kisii ))) Naivasha ))) Fort Hall ))) )))) Nyakibale CCSettlementSettlement ))) CCCKifunzoKifunzo Makiro ))) Rutshuru ))) Thika ))) Kabale ))) ))) Lake ))) ))) Bukoba NAIROBINAIROBI Kikungiri Victoria ))) ))) ))) ))) MwisaMwisa Athi River !! GisenyiGisenyi ))) MwisaMwisa !! ))) ByumbaByumba Machakos yy!!))) Goma ))) Kajiado RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA Magadi ))) KIGALIKIGALI KibuyeKibuye ))) KibungoKibungo ))) KibungoKibungo KENYAKENYA ))) KENYAKENYA ))) KENYAKENYA ))) KENYAKENYA ))) KENYAKENYA ))) GikongoroGikongoro NgaraNgara))) ))) NgaraNgara ))) !! ))) LukoleLukole A&BA&B MwanzaMwanza !! )))LukoleLukole A&BA&B MuganoMugano ))) )))MbubaMbuba SongoreSongore ))) ))) Ngozi ))) MuyingaMuyinga ))) Nyaruonga -

Transaction Costs and Smallholder Farmers' Participation in Banana

Center of Evaluation for Global Action Working Paper Series Agriculture for Development Paper No. AfD-0909 Issued in July 2009 Transaction Costs and Smallholder Farmers’ Participation in Banana Markets in the Great Lakes Region John Jagwe Emily Ouma Charles Machethe University of Pretoria International Institute of Tropical Agriculture This paper is posted at the eScholarship Repository, University of California. http://repositories.cdlib.org/cega/afd Copyright © 2009 by the author(s). Series Description: The CEGA AfD Working Paper series contains papers presented at the May 2009 Conference on “Agriculture for Development in Sub-Saharan Africa,” sponsored jointly by the African Economic Research Consortium (AERC) and CEGA. Recommended Citation: Jagwe, John; Ouma, Emily; Machethe, Charles. (2009) Transaction Costs and Smallholder Farmers’ Participation in Banana Markets in the Great Lakes Region. CEGA Working Paper Series No. AfD-0909. Center of Evaluation for Global Action. University of California, Berkeley. Transaction Costs and Smallholder Farmers’ Participation in Banana Markets in the Great Lakes Region John Jagwe1, 2, Emily Ouma2, Charles Machethe1 1Department of Agricultural Economics, Extension and Rural Development, University of Pretoria (LEVLO, 002, Pretoria, South Africa); 2International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Burundi, c/o IRAZ, B.P. 91 Gitega Keywords: smallholder farmers, market participation, transaction costs, bananas Abstract. This article analyses the determinants of the discrete decision of a household on whether to participate in banana markets using the FIML bivariate probit method. The continuous decision on how much to sell or buy is analyzed by establishing the supply and demand functions while accounting for the selectivity bias. Results indicate that buying and selling decisions are not statistically independent and the random disturbances in the buying and selling decisions are affected in opposite directions by random shocks. -

US Forest Service International Programs, Department of Agriculture

US Forest Service International Programs, Department of Agriculture Republic of Burundi Technical Assistance to the US Government Mission in Burundi on Natural Resource Management and Land Use Policy Mission Dates: September 9 – 22, 2006 Constance Athman Mike Chaveas Hydrologist Africa Program Specialist Mt. Hood National Forest Office of International Programs 16400 Champion Way 1099 14th St NW, Suite 5500W Sandy, OR 97055 Washington, DC 20005 (503) 668-1672 (202) 273-4744 [email protected] [email protected] Jeanne Evenden Director of Lands Intermountain Region 324 25th Street Ogden, UT 84401 (801) 625-5150 [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to extend our gratitude to all those who supported this mission to Burundi. In particular we would like acknowledge Ann Breiter, Deputy Chief of Mission at the US Embassy in Bujumbura for her interest in getting the US Forest Service involved in the natural resource management issues facing Burundi. We would also like to thank US Ambassador Patricia Moller for her strong interest in this work and for the support of all her staff at the US Embassy. Additionally, we are grateful to the USAID staff that provided extensive technical and logistical support prior to our arrival, as well as throughout our time in Burundi. Laura Pavlovic, Alice Nibitanga and Radegonde Bijeje were unrelentingly helpful throughout our visit and fountains of knowledge about the country, the culture, and the history of the region, as well as the various ongoing activities and actors involved in development and natural resource management programs. We would also like to express our gratitude to the Minister of Environment, Odette Kayitesi, for taking the time to meet with our team and for making key members of her staff available to accompany us during our field visits. -

The Burundi Peace Process

ISS MONOGRAPH 171 ISS Head Offi ce Block D, Brooklyn Court 361 Veale Street New Muckleneuk, Pretoria, South Africa Tel: +27 12 346-9500 Fax: +27 12 346-9570 E-mail: [email protected] Th e Burundi ISS Addis Ababa Offi ce 1st Floor, Ki-Ab Building Alexander Pushkin Street PEACE CONDITIONAL TO CIVIL WAR FROM PROCESS: THE BURUNDI PEACE Peace Process Pushkin Square, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Th is monograph focuses on the role peacekeeping Tel: +251 11 372-1154/5/6 Fax: +251 11 372-5954 missions played in the Burundi peace process and E-mail: [email protected] From civil war to conditional peace in ensuring that agreements signed by parties to ISS Cape Town Offi ce the confl ict were adhered to and implemented. 2nd Floor, Armoury Building, Buchanan Square An AU peace mission followed by a UN 160 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock, South Africa Tel: +27 21 461-7211 Fax: +27 21 461-7213 mission replaced the initial SA Protection Force. E-mail: [email protected] Because of the non-completion of the peace ISS Nairobi Offi ce process and the return of the PALIPEHUTU- Braeside Gardens, Off Muthangari Road FNL to Burundi, the UN Security Council Lavington, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254 20 386-1625 Fax: +254 20 386-1639 approved the redeployment of an AU mission to E-mail: [email protected] oversee the completion of the demobilisation of ISS Pretoria Offi ce these rebel forces by December 2008. Block C, Brooklyn Court C On 18 April 2009, at a ceremony to mark the 361 Veale Street ON beginning of the demobilisation of thousands New Muckleneuk, Pretoria, South Africa DI Tel: +27 12 346-9500 Fax: +27 12 460-0998 TI of PALIPEHUTU-FNL combatants, Agathon E-mail: [email protected] ON Rwasa, leader of PALIPEHUTU-FNL, gave up AL www.issafrica.org P his AK-47 and military uniform. -

An Estimated Dynamic Model of African Agricultural Storage and Trade

High Trade Costs and Their Consequences: An Estimated Dynamic Model of African Agricultural Storage and Trade Obie Porteous Online Appendix A1 Data: Market Selection Table A1, which begins on the next page, includes two lists of markets by country and town population (in thousands). Population data is from the most recent available national censuses as reported in various online databases (e.g. citypopulation.de) and should be taken as approximate as census years vary by country. The \ideal" list starts with the 178 towns with a population of at least 100,000 that are at least 200 kilometers apart1 (plain font). When two towns of over 100,000 population are closer than 200 kilometers the larger is chosen. An additional 85 towns (italics) on this list are either located at important transport hubs (road junctions or ports) or are additional major towns in countries with high initial population-to-market ratios. The \actual" list is my final network of 230 markets. This includes 218 of the 263 markets on my ideal list for which I was able to obtain price data (plain font) as well as an additional 12 markets with price data which are located close to 12 of the missing markets and which I therefore use as substitutes (italics). Table A2, which follows table A1, shows the population-to-market ratios by country for the two sets of markets. In the ideal list of markets, only Nigeria and Ethiopia | the two most populous countries | have population-to-market ratios above 4 million. In the final network, the three countries with more than two missing markets (Angola, Cameroon, and Uganda) are the only ones besides Nigeria and Ethiopia that are significantly above this threshold. -

L'origine De La Scission Au Sein U CNDD-FDD

AFRICA Briefing Nairobi/Brussels, 6 August 2002 THE BURUNDI REBELLION AND THE CEASEFIRE NEGOTIATIONS I. OVERVIEW Domitien Ndayizeye, but there is a risk this will not happen if a ceasefire is not agreed soon. This would almost certainly collapse the entire Arusha Prospects are still weak for a ceasefire agreement in framework. FRODEBU – Buyoya’s transition Burundi that includes all rebel factions. Despite the partner and the main Hutu political party – would Arusha agreement in August 2000 and installation have to concede the Hutu rebels’ chief criticism, of a transition government on 1 November 2001, the that it could not deliver on the political promises it warring parties, the Burundi army and the various made in signing Arusha. The fractious coalition factions of the Party for the Liberation of the Hutu would appear a toothless partner in a flawed People/National Liberation Forces (PALIPEHUTU- power-sharing deal with a government that had no FNL) and of the National Council for the Defense intention of reforming. All this would likely lead to of Democracy/Defense Forces of Democracy escalation rather than an end to fighting. (CNDD-FDD), are still fighting. Neither side has been able to gain a decisive military advantage, This briefing paper provides information about although the army recently claimed several and a context for understanding the rebel factions, important victories. whose history, objectives and internal politics are little known outside Burundi. It analyses their A ceasefire – the missing element in the Arusha dynamics, operational situations and negotiating framework – has been elusive despite on-going positions and is a product of extensive field activity by the South African facilitation team to research conducted in Tanzania and in Burundi, initiate joint and separate talks with the rebels. -

Economic and Social Council

UNITED NATIONS E Distr. Economic and Social GENERAL Council E/CN.4/1997/12/Add.1 7 March 1997 ENGLISH Original: FRENCH COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Fiftythird session Item 3 of the provisional agenda ORGANIZATION OF THE WORK OF THE SESSION Second report on the human rights situation in Burundi submitted by the Special Rapporteur, Mr. Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro, in accordance with Commission resolution 1996/1 Addendum Introduction 1. This document is an addendum to the second report by the Special Rapporteur on the human rights situation in Burundi to the Commission on Human Rights at its fiftythird session. 2. Section A of this addendum contains a number of observations by the Special Rapporteur on the most recent developments in the crisis in Burundi and section B a list of the most significant allegations made to him concerning violations of the right to life and to physical integrity during the past year. A. Observations on the most recent developments in the crisis in Burundi 3. The serious violations of the right to life and to physical integrity listed in this addendum are closely linked to the further developments in the crisis in Burundi caused by the interruption of the transition to democracy following the assassination of President Ndadaye on 21 October 1993, the acts of genocide perpetrated against the Tutsis and the subsequent massacres of Hutus. Nevertheless, the current situation in Burundi and its influence on the human rights situation are closely linked to the resurgence of rebel movements in eastern Zaire and to the return of Burundi and Rwandan refugees to their countries of origin.