Limitation of Liability and the Seaplane

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Felixstowe Flying-Boats

842 FLIGHT, 2 December 1955 The Porte Baby prototype No. 9800 in A its original form; later the bow section was lengthened. HISTORIC MILITARY AIRCRAFT Noll Part I By J. M. BRUCE, M.A. THE FELIXSTOWE FLYING-BOATS N 1909 a young British Naval officer named John Cyril Porte WITH this article on a famous family of flying-boats—about which made his first practical entry into the field of aviation by little detailed information has ever before appeared in print—Mr. Brace building a small glider which, in company with Lt. W. B. resumes his popular series. He wishes to make grateful acknowledgement I to Mr. Bruce Robertson, who has provided, together with certain other Pirie, R.N., he attempted to fly at Portsdown Hill, Portsmouth. information, the data on serial numbers which will be published with By the summer of 1910 Porte was experimenting with a little the final instalment of this article. monoplane of the Santos Dumont Demoiselle type, powered by a 35 h.p. Dutheil-Chalmers engine. At that time he was stationed at the Submarine Depot, Portsmouth, and his monoplane's trials several years. In that year he also made a three-wheeled road were conducted at Fort Grange. vehicle propelled by a crude airscrew which was driven by a small By the following year Po«e had fallen victim to pulmonary engine of his own design. tuberculosis, and his Naval career was apparently prematurely Curtiss had enjoyed a considerable amount of success with his terminated when he was invalided out of the Service. Despite his lightweight engines, a fact which had not escaped the attention of severe disability (for which medical science could at that time do the well-known American balloonist Thomas Scott Baldwin. -

Episode 6, NC-4: First Across the Atlantic, Pensacola, Florida and Hammondsport, NY

Episode 6, NC-4: First Across the Atlantic, Pensacola, Florida and Hammondsport, NY Elyse Luray: Our first story examines a swatch of fabric which may be from one of history’s most forgotten milestones: the world's first transatlantic flight. May 17th, 1919. The Portuguese Azores. Men in whaling ships watched the sea for their prey, harpoons at the ready. But on this morning, they make an unexpected and otherworldly sighting. A huge gray flying machine emerges from the fog, making a roar unlike anything they have ever heard before. Six American airmen ride 20,000 pounds of wood, metal, fabric and fuel, and plunge gently into the bay, ending the flight of the NC-4. It was journey many had thought impossible. For the first time, men had flown from America to Europe, crossing the vast Atlantic Ocean. But strangely, while their voyage was eight years before Charles Lindbergh's flight, few Americans have ever heard of the NC-4. Almost 90 years later, a woman from Saratoga, California, has an unusual family heirloom that she believes was a part of this milestone in aviation history. I'm Elyse Luray and I’m on my way to meet Shelly and hear her story. Hi. Shelly: Hi Elyse. Elyse: Nice to meet you. Shelly: Come on in. Elyse: So is this something that has always been in your family? Shelly: Yeah. It was passed down from my grandparents. Here it is. Elyse: Okay. So this is the fabric. Wow! It's in wonderful condition. Shelly: Yeah, it's been in the envelope for years and years. -

The First of the Great Flying Boats

America The first of the great flying boats BY JIM POEL AND LEE SACKETT America’s History would be up to the task. tiss had built. It also incorporated In 1914 Rodman Wannamaker To celebrate 100 years of peace many design features that stayed (of the department store fame) con- between the United States and in use throughout flying-boat pro- tracted Glenn Curtiss to build an England, in 1913 The London Daily duction in the coming years. The aircraft that was capable of flying Mail newspaper offered a prize of innovations included the stepped across the Atlantic Ocean. Not even $50,000 for the first aerial crossing hull, step vents, wing floats, spon- a decade had passed since Glenn of the Atlantic between the two sons, provisions for in-flight main- Curtiss and the Aerial Experiment countries. To further commemo- tenance, an enclosed cockpit, and Association (AEA) had flown the rate the strong bonds between even provisions for an in-cabin June Bug near Hammondsport, New England and the United States, mattress that would allow a crew- York. Aviation had made amazing there was to be both a British and member to rest. strides in the six years since the an American pilot. The aircraft was powered by two flight of the June Bug, but Wan- It only took 90 days to turn out 90-hp V-8 OX-5 engines and was namaker’s proposed flight seemed the Curtiss model H America, the designed to cruise at 55 to 60 mph. more “Jules Verne” than practi- world’s first multi-engine flying The instrument panel consisted of a cal. -

Report on Current Strength and Weaknesses of Existing Seaplane/ Amphibian Transport System As Well As Future Opportunities

Future Seaplane Transport System - SWOT Report on current strength and weaknesses of existing seaplane/ amphibian transport system as well as future opportunities Authors Giangi Gobbi, Ladislav Smrcek, Roderick Galbraith University of Glasgow Benedikt Mohr, Joachim Schömann, Institute of Aerospace Systems Technische Universität München Glasgow, UK Garching, Germany Keeper of Document Author or Coauthor Work Package(s) WP4 Status Draft Identification Programme, Project ID FP7-AAT-2007-RTD1 Project Title: FUture SEaplane TRAffic (FUSETRA) Version: 1.1 File name: FUSETRA_D41_SWOT_v01.doc FUSETRA – Future Seaplane Traffic 1 Version 1.0 Future Seaplane Transport System - SWOT 27.06.2011 Aerospace Engineering Glasgow University James Watt South Building Glasgow G12 8QQ UK Author: Giangi Gobbi Phone: +44.(0)141.330.7268 Fax: +44.(0)141.330.4885 [email protected] www.fusetra.eu FUSETRA – Future Seaplane Traffic 2 Version 1.0 Future Seaplane Transport System - SWOT Control Page This version supersedes all previous versions of this document. Version Date Author(s) Pages Reason 1.0 27/6/2011 Giangi Gobbi 46 Initial write/editing FUSETRA – Future Seaplane Traffic 3 Version 1.0 Future Seaplane Transport System - SWOT Contents List of tables ............................................................................................................... 6 List of figures .............................................................................................................. 6 Glossary .................................................................................................................... -

AIRCRFT Circuutrs

AIRCRFT CIRCUUtRS ::ATIo1AL ADVIOiY COITTEE FOR AEROTiUTICS No. 25 THE SUPE RIiE II SOUTHiFTON !i EEI2L-dE (Cbservation or 3ori'oer) From F1ight, tt 'TovTher 18 and. 25, 1926 VIa shin t on December ; 1926 NATIONAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE FOR AERONAUTICS. AIRCRAFT CIRCULAR NO. 25. THE SUPERMARINE "SOUTHAMPTON" SEAPLANE.* (Observation or Bomber) Having specialized for thirteen years on the design and con- struction of flying boats, it is not to be wondered at that the Supermarine Aviation Works have secured a leading position in this branch of aircraft work, and within the last year or so the firm has produced a seaplane which proved an instant success- and-large orders for which have been placed by the British Air Min- istry. This type has become known as the "Southampton," and the seaplane having gone into quantity production it has now be- come possible to give a detailed description of it, unfettered by the rules of secrecy which surround all aircraft built for the British Air Ministry until the restrictions are raised upon the seaplane being ordered in quantities. The Supemarine "Southampton," among its many other excellent features, incorDo- rates the somewhat unusual one of being able definitely to fly and maneuver with one of its two Napier "Lion" engines stopped. There are probably very few types of twin-engined aircraft in the world able to do this, and the fact that the "Southampton" will do it with comparative ease, speaks well for the design of / this seaplane. * From "Flight," November 18, and November 25, 1926. N.A.C.A. Aircarft Circular No. -

Tavares Seaplane Base Airport Master Plan

TAVARES SEAPLANE BASE AIRPORT MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT Prepared By: 5555 E. Michigan Street, Suite 200 Orlando, FL 32822 October 2017 TAVARES SEAPLANE BASE Master Plan Tavares, Florida Table of Contents 1. Inventory of Existing Conditions ....................................................................................... 1-1 1.1. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2. Seaplane Base Setting ............................................................................................. 1-1 1.2.1. Location ............................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2.2. Administration .................................................................................................... 1-2 1.3. Meteorological Conditions ......................................................................................... 1-2 1.3.1. Climate .............................................................................................................. 1-2 1.3.2. Wind Coverage .................................................................................................. 1-3 1.4. Historical Data .......................................................................................................... 1-4 1.4.1. Based Aircraft .................................................................................................... 1-4 1.4.2. Aircraft Operations ............................................................................................ -

They Stood the Watch…VP-11 at Kaneohe

They Stood the Watch… The Story of Patrol Squadron Eleven at NAS Kaneohe Bay By Dave Trojan, Hawaii Aviation Preservation Society Member A VP-11 crewman keeping watch in a PBY blister during a lengthy patrol (Photo courtesy of Robert O’Conner Collection) This is the story of Patrol Squadron Eleven (VP-11), a Navy PBY Catalina Patrol Squadron of WWII stationed at Naval Air Station Kaneohe Bay Hawaii. The purpose of this account is to tell the details of the mostly-untold description of this PBY Catalina squadron just prior to and at the beginning of WWII along with the horror and panic that greeted Patrol Squadron Eleven on that sleepy Sunday in December 1941. This chronicle also tries to capture the courage and self-sacrifice of those who kept the faith when hope was lost and their will to turn tragedy into triumph and defeat into victory. This story is pieced together from a variety of sources including war diaries, action reports, message traffic, official and personal correspondence, and other documents. This narrative is dedicated to the memory of those who gave their lives for their country, while serving in VP-11 during World War II. PBY Catalina’s fly over NAS Kaneohe Bay during base commissioning ceremony (Photo courtesy of Cliff Dohrmann Collection) NAS Kaneohe Bay was formally established on 15 February 1941 as a seaplane base for Navy patrol squadrons. In July 1941, Naval Air Station Kaneohe Bay became the headquarters of Patrol Wing One and VP-23 was the first to transfer to this newly commissioned Naval Air Station. -

Numerical Analysis of the Take-Off Performance of a Seaplane in Calm Water

applied sciences Article Numerical Analysis of the Take-Off Performance of a Seaplane in Calm Water Yang Guo , Dongli Ma, Muqing Yang * and Xing’an Liu School of Aeronautical Science and Engineering, Beihang University, Beijing 100191, China; [email protected] (Y.G.); [email protected] (D.M.); [email protected] (X.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Featured Application: This paper provided a numerical approach to predict the resistance and attitude of a seaplane taking off in calm water. The investigations on take-off performance of the seaplane would provide some guidance in the integrated design of aerodynamics and hydrody- namics of the seaplanes. Abstract: Nowadays, with the escalating tensions in maritime dispute and the development of marine economy, there has been renewed interest in seaplanes for their special capacity of taking off and landing on water. Prediction of take-off performance, involving aerodynamic analysis and hydrodynamic analysis, is a main challenge in seaplane design, while the prediction methods have been little improved since the 1960s. This paper aims to investigate the attitude and resistance characteristics of a seaplane at different speeds during the take-off by numerically modeling the air-water flow field using RANS equations with VOF method. The trim and heave motion of seaplane in response to aerodynamic forces, hydrodynamic forces, hydrostatic forces, and propeller thrust was realized by solving rigid body dynamics equations and adopting dynamic overset mesh technique. The variations in heave, trim angle, and resistance characteristics during the takeoff were investigated, Citation: Guo, Y.; Ma, D.; Yang, M.; and their inherent relationships with the aerodynamic, hydrodynamic, and hydrostatic performance Liu, X. -

Blast from the Past

RNZAF Sunderland Memories by Robin Klitscher Ref: http://rnzaf.proboards.com/thread/18188 http://www.5sqnassn.org.nz/ SUNDERLAND ON PATROL, NINETEEN FIFTYSOMETHING. PART 1 Flying Sunderland "boats" on maritime patrol seemed always to mean getting up at an unsociable hour. Perhaps because they cruised so leisurely, it was necessary to take off at the crack of dawn, or earlier, in order to be sure of doing anything very much before nightfall. Having arisen however reluctantly, the immediate purpose is to satisfy the engrossing hunger that is a part of such small hours. A sympathetic system makes available a breakfast of monumental proportions at the Combined Mess. Then to the squadron for briefing. Close-in, lights on the hard-standing reflect on the water in the pre-dawn stillness. Farther out, the water ripples in light airs coming down the channel. Ground crew are busy. Marine Section tenders fuss around the jetty, and ruffle the surface between shore and aircraft. The control launch is readying to put out. In the operations room the navigators plot the patrol on their charts. The weather will be mostly broken cloud, some showers, wind on average 350 degrees at 15 knots, except for a front lying across the route about five hours out. They hunch over their computers - not the modern digital variety, but a device with a circular slide rule on one side and a wind-and-course triangulation gizmo on the other. The flight engineers worry about fuel load and all-up weight; and the signallers about frequencies, morse keys and code books. -

Seaplane Design - a Forgotten Art

Verein Deutscher Ingenieure Hamburger Bezirksverein e.V. Arbeitskreis Luft- und Raumfahrt Hamburg Aerospace Lecture Series Hamburger Luft- und Raumfahrtvorträge DGLR in cooperation with the RAeS, HAW Hamburg, VDI, & ZAL invites you to a lecture Seaplane Design - A Forgotten Art Prof. Dr.-Ing. Elmar Wilczek, Expert in Marine Aviation Lecture followed by discussion Date: Thursday, 20 May 2021, 18:00 CEST No registration required ! Online Zoom lecture Online: http://purl.org/ProfScholz/zoom/2021-05-20 Beriev Be-200 Altair – Courtesy of United Aircraft Corporation (UAC) A seaplane gives the ultimate freedom of flight with theoretically endless take-off and alighting possibilities along the coast, on lakes and rivers – and not to forget on the open seas. The design of seaplanes is based on the knowledge of aircraft design and speedboat design. The craft must meet buoyancy and lift requirements. Hydrostatic and -dynamic stability has to be matched with the longitudinal and lateral static and dynamic stability in the air. The structure has to withstand water and air loads. Crucial are hydrodynamic resistance at take-off as well as the lift-to-drag ratio in flight and particularly the water loads in defined sea states. Sea plane design has a glorious past, but much of the knowledge is buried in dusty archives. It is even worse if knowledge is lost forever and needs to be reinvented. Elmar Wilczek has taught seaplane design for decades. In his presentation he will focus on particular research results among others: the importance of water spray for hydrodynamic resistance, scale effects, hydrodynamic elasticity for seaworthiness, length-to-beam ratio for hydrodynamics and aerodynamics. -

PENNSYLVANIA PILOT Vol 23 No 3, Fall 2012

AERO CLUB OF PENNSYLVANIA PENNSYLVANIA PILOT Vol 23 No 3, Fall 2012 www.aeroclubpa.org Published quarterly by the Aero Club of Pennsylvania for those interested in aviation in the Greater Delaware Valley Event Planning Aero Club and Ninety-Nines award $29,000... Wings and Wheels... 17 recipients awarded Balloon rises above PACC The Aero Club will have a table Over 60 members, recipients and Following the July 19 Aero Club setup at the annual Wings & family members attended the annual Board of Directors meeting, our Wheels Day on September 8 at scholarship dinner on June 14 at special guest Keith Sproul demon- Wings Field. The event is an Wings Field. The Aero Club of strated the inflation and tethering of annual fundraiser for Angel Pennsylvania Memorial Scholarship a one-person, hot air balloon. About Flight East, but the Aero Club Fund along with the Eastern PA 30 members and local pilots got up also sells aviation items to raise Chapter of the Ninety-Nines award- close to the balloon as it funds for the Aero Club Memori- ed nearly $29,000 to 17 recipients. was inflated on the al Scholarship Fund. Aero awards totaling nearly grounds of the $23,000 were given predomi- Philadelphia Eagles Mere... nantly to post-solo students, Aviation Coun- The Aero Club planned to make a but four awards were given in try Club at private visit to the Eagles Mere honor of Bob Shannon to Wings Field. A Aviation Museum in northern deserving students to start their number of brave Pennsylvania on August 5 about primary training. -

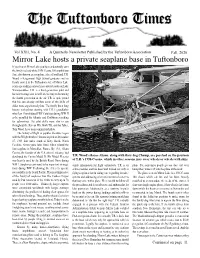

Mirror Lake Hosts a Private Seaplane Base in Tuftonboro

Vol XXII, No. 4 A Quarterly Newsletter Published by the Tuftonboro Association Fall, 2020 Mirror Lake hosts a private seaplane base in Tuftonboro If you live on Mirror Lake you have undoubtedly seen the lovely red and white 1956 Cessna 180 amphibious float, also known as a seaplane, take off and land. T.R. Wood, a Kingswood High School graduate and his family moved to the Tuftonboro side of Mirror Lake years ago seeking a slower pace after decades on Lake Winnipesaukee. T.R. is a third-generation pilot and his near-teenage son is well on his way to becoming the fourth generation in the air. T.R. is quite proud that his son already exhibits some of the skills of older, more experienced pilots. The family has a long history with planes starting with T.R.’s grandfather who flew Consolidated PBY Catalinas during WW II as he patrolled the Atlantic and Caribbean searching for submarines. His pilot skills were also in use throughout the Korean War. Both T.R. and his father, Tom Wood, have been commercial pilots. The history of flight in popular literature began with the Wright brothers’ famous exploit on December 17, 1903 four miles south of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Seven years later Henri Fabre piloted the first seaplane in Marseilles, France. By 1911, Glenn Curtiss, the founder of the U.S. aircraft industry, had developed the Curtiss Model D. His Model H series T.R. Wood’s fiance Alison, along with their dog Champ, are perched on the pontoon was heavily used by the British Royal Navy during of T.R.’s 1956 Cessna, which in other seasons may wear wheels or wheels with skiis.