Market Timing: Opportunities and Risks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Secondary Market Trading Infrastructure of Government Securities

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Balogh, Csaba; Kóczán, Gergely Working Paper Secondary market trading infrastructure of government securities MNB Occasional Papers, No. 74 Provided in Cooperation with: Magyar Nemzeti Bank, The Central Bank of Hungary, Budapest Suggested Citation: Balogh, Csaba; Kóczán, Gergely (2009) : Secondary market trading infrastructure of government securities, MNB Occasional Papers, No. 74, Magyar Nemzeti Bank, Budapest This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/83554 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu MNB Occasional Papers 74. 2009 CSABA BALOGH–GERGELY KÓCZÁN Secondary market trading infrastructure of government securities Secondary market trading infrastructure of government securities June 2009 The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official view of the central bank of Hungary (Magyar Nemzeti Bank). -

Dynamic Portfolio Optimization with Transaction Cost Abstract

Financial Engineering and Portfolio Management / Vol.6, Issue.24, Autumn 2015 Dynamic Portfolio Optimization with Transaction Cost 1 Zahra Pourahmadi 2 Amir Abbas Najafi Receipt: 2015, 2 , 3 Acceptance: 2015, 4 , 29 Abstract The optimal selection of portfolio is one the most important decisions in managing investment funds. Several approaches have been proposed to determine what is the best trading strategy. Most of these common approaches are based on single period optimization, however, as investment is a long-term concept, such short term profit maximization cannot fully exploit the opportunities that an investor might get if he/she looks into a longer term. To this end, in this paper, we intend to extend the single-period optimization into a multi-period optimization and also, to make it more realistic, we will incorporate transaction cost in our model. To investigate the validity of the proposed scheme, we have analyzed several examples using which we have presented the steps of our approach and also statistically compared the performance of the single and multi- period optimization using Mann-Whitney U test. Based on the results of this paper, we can conclude that multi-period and single-period optimization might have similar performance if we look at short time span of the system. However the superiority of multi-period optimization becomes more evident as we extend the time span of the system which gives multi-period scheme more freedom to suggest better portfolio selections. Key Words: Portfolio, Dynamic Optimization, Transaction Cost, Investment Strategy 1 Financial Engineering Master Student, K.N. Toosi University of Technology 2 Assistant Professor, Faculty of Financial Engineering, K. -

Complete Guide for Trading Pump and Dump Stocks

Complete Guide for Trading Pump and Dump Stocks Pump and dump stocks make me sick and just to be clear I do not trade these setups. When I look at a stock chart I normally see bulls and bears battling to see who will come out on top. However, when I look at a pump and dump stock it just saddens me. For those of you that watched the show Spartacus, it’s like when Gladiators have to fight outside of the arena and in dark alleys. As I see the sharp incline up and subsequent collapse, I think of all the poor souls that have lost IRA accounts, college savings and down payments for their homes. Well in this article, I’m going to cover 2 ways you can profit from these setups and clues a pump and dump scenario is taking place. Before we hit the two strategies, let’s first ground ourselves on the background of pump and dump stocks. What is a Pump and Dump Stock? These are stocks that shoot up like a rocket in a short period of time, only to crash down just as quickly shortly thereafter. The stocks often come out of nowhere and then the buzz on them reaches a feverish pitch. We can break the pump and dump down into three phases. Pump and Dump Phases Phase 1 – The Markup Every phase of the pump and dump scheme are challenging, but phase one is really tricky. The ring of thieves need to come up with an entire plan of attack to drum up excitement for the security but more importantly people pulling out their own cash. -

Signs of a Slowdown Cast a Shadow Over Markets

Benjamin H Cohen (+41 61) 280 8921 [email protected] I. Overview of developments: Signs of a slowdown cast a shadow over markets During the fourth quarter of 2000, investors’ expectations of a slowing global economy contributed to a downward shift in yield curves, a widening of credit spreads and further declines in already weak equity markets. Market attention focused on the United States, where macroeconomic data reinforced the view that a slowdown was likely in the first half of 2001. Profit warnings and credit downgrades also weighed heavily on the equity and debt markets and signalled problems of excessive leverage in the corporate sector. Even the normally stable commercial paper markets experienced unusually wide and volatile credit spreads. Market movements also revealed the extent to which the US outlook led to a re-evaluation of growth prospects in other regions. An appreciation of the euro suggested that investors viewed the European economy as likely to maintain momentum, although a downward shift in the euro swaps curve also indicated a potential exposure to the impact of a US slowdown. A depreciation of the yen and a decline in the Tokyo stock market reflected perceptions of a return to weaker growth in Japan. Divergent sovereign spreads corresponded to distinctions investors made in their judgments about the outlook for the emerging economies, with some countries seen as facing severe challenges and others as experiencing an uneven but persistent recovery from recent crises. Markets in general turned around in January 2001. A surprise 50 basis point reduction in the Federal Reserve’s target for the federal funds rate on 3 January, followed by a further 50 basis point cut on 31 January, buoyed both the equity and bond markets, at least temporarily. -

Performance of Stop-Loss Rules Vs. Buy-And-Hold

LUND UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND MANAGEMENT NEKM01, MASTER ESSAY IN FINANCE SPRING 2009 PERFORMANCE OF STOP -LOSS RULES VS . BUY -AND -HOLD STRATEGY AUTHORS : SUPERVISOR : Bergsveinn Snorrason Göran Anderson Garib Yusupov ii ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to investigate the performance of traditional stop-loss rules and trailing stop-loss rules compared to the classic buy-and-hold strategy. The evaluation criteria of whether stop-loss strategies can deliver better results are defined as return and volatility. The study is conducted on daily equity returns data for stocks listed on the OMX Stockholm 30 Index during the time period between January 1998 and April 2009 divided into holding periods of three months. We use the Efficient Market Hypothesis as the rule of thumb and choose an arbitrary starting date for the holding periods. We test the performance of two types of stop-loss strategies, trailing stop-loss and traditional stop-loss. Despite the methodological differences our results are in line with previous research done by Kaminski and Lo (2007), where they find that stop-loss strategies have a positive marginal impact on both expected returns and risk-adjusted expected returns. In our research we find strong indications of the stop-loss strategies being able to outperform the buy-and-hold portfolio strategy in both criteria. The empirical results indicate that the stop-loss strategies can do better than the buy-and-hold even clearer cut when compared in terms of the risk-adjusted returns. Keywords: Stop-loss, Trailing Stop-loss, Buy-and-Hold, Behavioral Finance, Strategy iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................... -

Speculation in the United States Government Securities Market

Authorized for public release by the FOMC Secretariat on 2/25/2020 Se t m e 1, 958 p e b r 1 1 To Members of the Federal Open Market Committee and Presidents of Federal Reserve Banks not presently serving on the Federal Open Market Committee From R. G. Rouse, Manager, System Open Market Account Attached for your information is a copy of a confidential memorandum we have prepared at this Bank on speculation in the United States Government securities market. Authorized for public release by the FOMC Secretariat on 2/25/2020 C O N F I D E N T I AL -- (F.R.) SPECULATION IN THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT SECURITIES MARKET 1957 - 1958* MARKET DEVELOPMENTS Starting late in 1957 and carrying through the middle of August 1958, the United States Government securities market was subjected to a vast amount of speculative buying and liquidation. This speculation was damaging to mar- ket confidence,to the Treasury's debt management operations, and to the Federal Reserve System's open market operations. The experience warrants close scrutiny by all interested parties with a view to developing means of preventing recurrences. The following history of market events is presented in some detail to show fully the significance and continuous effects of the situation as it unfolded. With the decline in business activity and the emergence of easier Federal Reserve credit and monetary policy in October and November 1957, most market elements expected lower interest rates and higher prices for United States Government securities. There was a rapid market adjustment to these expectations. -

US Commercial Banks' Securities

ecommunications hqnittee on Energy and Commerce, House of Representatives - September 1988 INTERNATIONAL FINANCE a United States General Accounting Office Washington, D.C. 20548 Comptroller General of the United States B-229444 September 8, 1988 The Honorable Edward J. Markey Chairman, Subcommittee on Telecommunications and Finance Committee on Energy and Commerce House of Representatives Dear Mr. Chairman: At your request, we reviewed how U.S. commercial banks performed their securities underwriting and trading activities in the London mar- kets’ during 1986 and 1987 to assess how they might handle such activi- ties within the United States if the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 were revised or repealed. The Glass-Steagall Act’s prohibition against the underwriting and trad- ing of corporate debt and equity securities by commercial banks applies to business conducted within the United States. According to the Federal Reserve’s Regulation K,’ banks may underwrite and trade securities outside the United States, within certain limits. These activities may be undertaken by subsidiaries of the bank holding company or by subsidi- aries of the bank itself, but not by branches, which are permitted to underwrite only local government securities. U.S. commercial banks conduct the greatest concentration of their over- seas underwriting and trading activities in London. Approximately 50 U.S. commercial banks operate in London, and 18 of them engage in at least a minimal amount of underwriting and trading. The range and type of such activities varies among these 18 banks. Most are large banks; 16 are considered money-center or super-regional banks. Bank examination reports from the Federal Reserve, the New York State Banking Department, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency indicate that most of the London securities subsidiaries of U.S. -

History of the Stock Market

Contributing Writers: Douglas Alexander, Pamela Fung, NIE A Newspaper In Education Supplement to Pauline Schafer, Laura Levine News In Education What is the Stock Market? But the stock market is different from a shopping mall in some important ways. Most noticeably, you don't find all stock The Washington Times The Washington exchanges under one roof. In fact, in the United States, there are stock exchanges in many parts of the country and electronic stock markets can operate from almost any remote location. The other important difference is that at the shopping mall, stores sell products to the customers. But in the stock market, investors buy and sell stock, to and from each other. That's a bit complicated, so we'll examine it more closely, later. Sometimes we hear the stock market simply called "the mar- ket." That can be a bit confusing, since there are many types of "markets" in the world. But generally, when we hear the term on television or read it in the newspaper in the business and finance section, it's pretty safe to assume that "the mar- A Newspaper in Education Supplement to A Newspaper ket" is short for "the stock market." You may have also heard or read about "Wall Street." This is another nickname for the stock market, which comes from the actual street in New York City where the stock market, in this country, began. NEWSPAPER ACTIVITIES 1. Look through the business pages of your newspaper for how the stock market has done in the past year or two. If there is a chart that compares stock performance with bond investments or money market funds, list the relative performance of each of these types of investments. -

The Benchmark US Treasury Market: Recent Performance

Michael J. Fleming The Benchmark U.S. Treasury Market: Recent Performance and Possible Alternatives he U.S. Treasury securities market is a benchmark. As crisis in the fall of 1998 in a so-called “flight to quality.” A Tobligations of the U.S. government, Treasury securities are related “flight to liquidity” also caused yield spreads among considered to be free of default risk. The market is therefore a Treasury securities of varying liquidity to widen sharply. benchmark for risk-free interest rates, which are used to Consequently, some of the attributes that make the Treasury forecast economic developments and to analyze securities in market an attractive benchmark were adversely affected. other markets that contain default risk. The Treasury market is This paper examines the benchmark role of the U.S. also large and liquid, with active repurchase agreement (repo) Treasury market and the features that make it an attractive and futures markets. These features make it a popular benchmark. In it, I examine the market’s recent performance, benchmark for pricing other fixed-income securities and for including yield changes relative to other fixed-income markets, hedging positions taken in other markets. changes in liquidity, repo market developments, and the The Treasury market’s benchmark status, however, is now aforementioned flight to liquidity. I show that several of the being called into question by the nation’s improved fiscal attributes that make the U.S. Treasury market a useful situation. The U.S. government has run a budget surplus over benchmark were negatively affected by the events of fall 1998, the past two years, and surpluses are expected to continue (and and that some of these attributes did not quickly return to their to continue growing) for years. -

L-Shares: Rewarding Long-Term Investors1

1 L-Shares: Rewarding Long-term Investors by Patrick Bolton Columbia University and Frédéric Samama SWF Research Initiative and Amundi – Crédit Agricole Group November 2012 Abstract: We argue that a fundamental reason for the short term perspective of corporate executives is the short-term orientation of shareholders and financial markets that drive the performance benchmarks of CEOs. In our view, long-term committed shareholders can provide substantial benefits to the company they invest in and although some shareholders are prepared to take a more long-term view, they are generally not rewarded for their loyalty to the company. We believe that because they are a scarce resource and provide benefits to the company and other shareholders that have all the features of a public good, long-term shareholders need to receive financial incentives. While lengthening stock option vesting periods and introducing claw-back provisions into CEO compensation contracts help induce a more long-term orientation of CEOs, we argue that it is also necessary to reinforce this more long-term performance-based compensation with a better alignment between shareholders and CEOs horizons. Our proposal for moving towards such an alignment is to introduce Loyalty- Shares (or L-shares). These shares provide an additional reward (usually under the form of an extra-share or extra-dividend) to shareholders if they have held on to their shares for a contractually specified period of time, the loyalty period. The reward we propose, which we believe would be a more optimal solution in many cases, is in the form of a warrant giving the right to purchase a pre-determined number of new shares at a pre-specified price and granted to loyal investors at the expiration of the loyalty period. -

IPO Market Timing

IPO Market Timing Aydog˘an Altı University of Texas at Austin I develop a model of information spillovers in initial public offerings (IPOs). The outcomes of pioneers’ IPOs reflect participating investors’ private information on common valuation factors. This makes the pricing of subsequent issues relatively easier and attracts more firms to the IPO market. I show that IPO market timing by the followers emerges as an equilibrium clustering pattern. High offer price realizations for pioneers’ IPOs better reflect investors’ private information and trigger a larger number of subsequent IPOs than low offer price realizations do. This asymmetry in the spillover effect is more pronounced early on in a hot market. The model provides an explanation for recent empirical findings that illustrate the high sensitivity of going public decision to IPO market conditions. Clustering of initial public offerings (IPOs) is a well-documented phe- nomenon. Starting with Ibbotson and Jaffe (1975), several studies have shown that IPOs tend to cluster both in time and in industries.1 What causes these hot and cold market cycles is less clear, however. While the IPO clustering could potentially be due to clustering of real investment opportunities, empirical findings suggest that this link is weak. Most IPO firms do not have urgent funding needs [Pagano, Panetta, and Zingales (1998)]; instead, firms’ equity-issue decisions seem to be driven mainly by market timing attempts [Baker and Wurgler (2002)]. Furthermore, hot versus cold market IPO firms do not appear to differ in their growth prospects or future operating performance [Helwege and Liang (2002)]. Recent empirical research has focused on information spillovers as the main driver of the hot market phenomenon. -

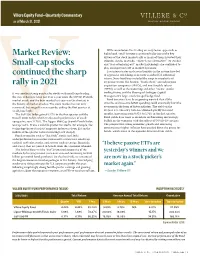

Market Review: Small-Cap Stocks Continued the Sharp Rally in 2021

Villere Equity Fund—Quarterly Commentary as of March 31, 2021 With commission-free trading on easy-to-use apps such as Market Review: Robinhood, retail investors continued to be one of the key drivers of the stock market rally as many of them invested their stimulus checks in stocks. “There-is-no-alternative” (to stocks) Small-cap stocks and “fear-of-missing-out” market psychology also continued to play an important role in market dynamics. Low interest rates and excess liquidity in the system have led continued the sharp to aggressive risk taking as investor searched for additional return. News headlines included the surge in popularity of cryptocurrencies like bitcoin, “blank check” special purpose rally in 2021 acquisition companies (SPACs), and non-fungible tokens (NFTs), as well as the GameStop and other “meme” stocks It was another strong quarter for stocks with small caps leading trading frenzy, and the blow-up of Archegos Capital the way. It has now been just over a year since the COVID-19 stock Management’s large, overleveraged hedge fund. market crash, and the bear market last year was the shortest in Bond investors have been growing worried that all the the history of market crashes. The stock market has not only stimulus and massive deficit spending could eventually hurt the recovered, but surged to new records, ending the first quarter at economy in the form of faster inflation. The yield on the an all-time high. 10-year U.S. Treasury Note has climbed quickly in recent The S&P 500 Index gained 6.17% in the first quarter and the months, increasing from 0.93% to 1.74% in the first quarter.