Cineaste Style Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Ani 15-24

DE ANI 15-24 MARTIE 2019 12 Festival Internațional de Documentar și Drepturile Omului 15-24 MARTIE 2019 12 Festival Internațional de Documentar și Drepturile Omului CINEMA ELVIRE POPESCO CINEMATECA EFORIE CINEMATECA UNION ARCUB POINT PAVILION 32 INFO & BILETE WWW.ONEWORLD.RO FACEBOOK: ONE.WORLD.ROMANIA ORGANIZATOR / ORGANIZER Asociația One World Romania PARTENER PRINCIPAL / MAIN PARTNER Programul Statul de Drept Europa de Sud Est al Fundației Konrad Adenauer CU SPRIJINUL / WITH THE SUPPORT OF Administrația Fondului Cultural Național, Centrul Național al Cinematografiei, Primăria Capitalei prin ARCUB – Centrul Cultural al Municipiului București, UNHCR – Agenția ONU pentru Refugiați, Reprezentanța Comisiei Eu- ropene în România, Uniunea Cineaștilor din România, DACIN-SARA, Organizația Internațională pentru Migrație, Institutul Cultural Român, Institutul de Investigare a Crimelor Comunismului și Memoria Exilului Românesc, Con- siliul Național pentru Combaterea Discriminării, Agenția de Cooperare Internaționalâ pentru Dezvoltare - RoAid SPONSORI / SPONSORS BOSCH, Aqua Carpatica, Domeniile Sâmburești CINEMA ELVIRE POPESCO PARTENERI / PARTNERS Ambasada Franței în România, Institutul Francez din București, Goethe-Institut București, Ambasada Statelor PARTENERI CINEMATECA EFORIE Unite ale Americii, Ambasada Regatului Țărilor de Jos în România, Forumul Cultural Austriac, Swiss Sponsor’s Fund, Ambasada Elveției în România, British Council, Ambasada Statului Palestina, Centrul Cultural Palestin- CINEMATECA UNION ian “Mahmoud Darwish”, Festivalul -

Route 181 Fragments of a Journey in Palestine-Israel a Film by Michel Khleifi & Eyal Sivan

Momento!, Sourat Films & Sindibad Films present Route 181 Fragments of a Journey in Palestine-Israel A film by Michel Khleifi & Eyal Sivan English-language Press-pack (Digital photographs will be provided on request) Contact Information: Sindibad Films Limited, 5 Princes Gate, London SW7 1QJ, UK Tel: + 44 207 823 74 88, Fax: + 44 207 823 91 37 Email: [email protected] , http://www.sindibad.co.uk Or Momento! email: [email protected] Tel + 33 1 43 66 25 24 Fax + 33 1 43 66 86 00 http://www.momento-productions.com Momento!, Sourat Films & Sindibad Films present Route 181 – Fragments of a Journey in Palestine-Israel A film by Michel KHLEIFI & Eyal SIVAN Route 181 offers an unusual vision of the inhabitants of Palestine-Israel, a common vision of a Palestinian and an Israeli. For more than a year now, Khleifi and Sivan have dedicated themselves to producing what they consider a cinematic act of faith: a film co-directed by a Palestinian and by an Israeli. In the summer of 2002, for two long months, they travelled together from the south to the north of their country of birth, traced their trajectory on a map and called it Route 181. This virtual line follows the borders outlined in Resolution 181, which was adopted by the United Nations on November 29th 1947 to partition Palestine into two states. As they travel along this route, they meet women and men, Israeli and Palestinian, young and old, civilians and soldiers, filming them in their everyday lives. Each of these characters has their own way of evoking the frontiers that separate them from their neighbours: concrete, barbed-wire, cynicism, humour, indifference, suspicion, aggression…Frontiers have been built on the hills and in the plains, on mountains and in valleys but above all inside the minds and souls of these two peoples and in the collective unconscious of both societies. -

A Film by Catherine BREILLAT Jean-François Lepetit Présents

a film by Catherine BREILLAT Jean-François Lepetit présents WORLD SALES: PYRAMIDE INTERNATIONAL FOR FLASH FILMS Asia Argento IN PARIS: PRESSE: AS COMMUNICATION 5, rue du Chevalier de Saint George Alexandra Schamis, Sandra Cornevaux 75008 Paris France www.pyramidefilms.com/pyramideinternational/ IN PARIS: Phone: +33 1 42 96 02 20 11 bis rue Magellan 75008 Paris Fax: +33 1 40 20 05 51 Phone: +33 (1) 47 23 00 02 [email protected] Fax: +33 (1) 47 23 00 01 a film by Catherine BREILLAT IN CANNES: IN CANNES: with Cannes Market Riviera - Booth : N10 Alexandra Schamis: +33 (0)6 07 37 10 30 Fu’ad Aït Aattou Phone: 04.92.99.33.25 Sandra Cornevaux: +33 (0)6 20 41 49 55 Roxane Mesquida Contacts : Valentina Merli - Yoann Ubermulhin [email protected] Claude Sarraute Yolande Moreau Michael Lonsdale 114 minutes French release date: 30th May 2007 Screenplay: Catherine Breillat Adapted from the eponymous novel by Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly Download photos & press kit on www.studiocanal-distribution.com Produced by Jean-François Lepetit The storyline This future wedding is on everyone’s lips. The young and dissolute Ryno de Marigny is betrothed to marry Hermangarde, an extremely virtuous gem of the French aristocracy. But some, who wish to prevent the union, despite the young couples’ mutual love, whisper that the young man will never break off his passionate love affair with Vellini, which has been going on for years. In a whirlpool of confidences, betrayals and secrets, facing conventions and destiny, feelings will prove their strength is invincible... Interview with Catherine Breillat Film Director Photo: Guillaume LAVIT d’HAUTEFORT © Flach Film d’HAUTEFORT Guillaume LAVIT Photo: The idea “When I first met producer Jean-François Lepetit, the idea the Marquise de Flers, I am absolutely “18th century”. -

FILMS on Palestine-Israel By

PALESTINE-ISRAEL FILMS ON THE HISTORY of the PALESTINE-ISRAEL CONFLICT compiled with brief introduction and commentary by Rosalyn Baxandall A publication of the Palestine-Israel Working Group of Historians Against the War (HAW) December 2014 www.historiansagainstwar.org Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution – NonCommercial – ShareAlike 1 Introduction This compilation of films that relate to the Palestinian-Israeli struggle was made in July 2014. The films are many and the project is ongoing. Why film? Film is often an extraordinarily effective tool. I found that many students in my classes seemed more visually literate than print literate. Whenever I showed a film, they would remember the minute details, characters names and sub-plots. Films were accessible and immediate. Almost the whole class would participate and debates about the film’s meaning were lively. Film showings also improved attendance at teach-ins. At the Truro, Massachusetts, Library in July 2014, the film Voices Across the Divide was shown to the biggest audiences the library has ever had, even though the Wellfleet Library and several churches had refused to allow the film to be shown. Organizing is also important. When a film is controversial, as many in this pamphlet are, a thorough organizing effort including media coverage will augment the turnout for the film. Many Jewish and Palestinian groups list films in their resources. This pamphlet lists them alphabetically, and then by number under themes and categories; the main listings include summaries, to make the films more accessible and easier to use by activist and academic groups. 2 1. 5 Broken Cameras, 2012. -

(Anna Condo) in Wedding in Galilee, a Figure of Transition Between the Allure of Traditional Femininity and the Enactment of Phallic Authority

The bride (Anna Condo) in Wedding in Galilee, a figure of transition between the allure of traditional femininity and the enactment of phallic authority. Courtesy of Kino Film Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/camera-obscura/article-pdf/23/3 (69)/1/400972/CO69_01_Ball.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 Between a Postcolonial Nation and Fantasies of the Feminine: The Contested Visions of Palestinian Cinema Anna Ball In the relatively youthful field of Palestinian filmmaking, Wedding in Galilee (Urs al-jalil, dir. Michel Khleifi, Palestine/France/Bel- gium, 1987) and Divine Intervention (Yadun ilaheyya, dir. Elia Sulei- man, France/Morocco/Germany/Palestine, 2002) represent sig- nificant contributions to their national cinema at crucial points in its development and in the nation’s history. Khleifi’s work opposed the militant propagandist tone of films produced by the Pales- tine Liberation Organization (PLO) following the Six-Day War of 1967, which saw significant territorial gains by Israel and became known as al-Naksa, the setback or disaster, to Palestinians.1 Wed- ding in Galilee’s unusually lyrical, meditative style drew attention for the way it seemed to capture a profound sense of uncertainty in Palestinian nationhood. Its thoughtful ambivalence, or what might now be read in terms of its status as “accented cinema,”2 made it the first Palestinian feature film to achieve international recognition, gaining the International Critics’ prize at Cannes in Camera Obscura 69, Volume 23, Number 3 doi 10.1215/02705346-2008-006 © 2008 by Camera Obscura Published by Duke University Press 1 Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/camera-obscura/article-pdf/23/3 (69)/1/400972/CO69_01_Ball.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 2 • Camera Obscura 1987. -

LE MONDE/PAGES<UNE>

www.lemonde.fr 58 ANNÉE – Nº 17858 – 1,20 ¤ – FRANCE MÉTROPOLITAINE --- MERCREDI 26JUIN 2002 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI Police, préfets : première vague Bush : la Palestine, sans Arafat de nominations LES ISRAÉLIENS ont salué et f les Palestiniens ont dénoncé le dis- George W. Bush DIX SEPT préfets désignés ou cours dans lequel le président appelle à écarter mutés, un nouveau directeur géné- George W. Bush a appelé, lundi ral de la police nationale, un autre 24 juin, au départ de Yasser Arafat Yasser Arafat directeur central de la sécurité publi- en préalable à l’établissement d’un que, changements à la DST, à la PJ : Etat en Cisjordanie et à Gaza. Le f Il propose neuf jours après le second tour des premier ministre israélien, Ariel élections législatives, le gouverne- Sharon, a la satisfaction de voir le la création ment a décidé, mardi 25 juin au con- président américain prendre en seil des ministres, une première compte sa principale demande : le d’un Etat palestinien série de nominations stratégiques départ ou la marginalisation politi- d’ici à 2005 au sommet de l’administration. que du chef de l’Autorité palesti- D’autres suivront dans l’éducation nienne. Pour Dany Naveh, minis- f nationale, la justice et la diplomatie. tre sans portefeuille et proche de Sharon satisfait, M. Sharon, « la fin de l’ère Arafat l’OLP hostile Lire page 7 est une victoire pour Israël ». Le bureau de M. Sharon n’a pas com- HANDICAPÉS menté l’appel de M. Bush à la créa- f Enquête : tion d’un Etat palestinien dans les les juifs américains Nouvelle polémique territoires occupés, selon ses pro- pres termes, d’ici à 2005. -

German Films Quarterly 2 · 2004

German Films Quarterly 2 · 2004 AT CANNES In Competition DIE FETTEN JAHRE SIND VORBEI by Hans Weingartner FULFILLING EXPECTATIONS Interview with new FFA CEO Peter Dinges GERMAN FILM AWARD … and the nominees are … SPECIAL REPORT 50 Years Export-Union of German Cinema German Films and IN THE OFFICIAL PROGRAM OF THE In Competition In Competition (shorts) In Competition Out of Competition Die Fetten Der Tropical Salvador Jahre sind Schwimmer Malady Allende vorbei The Swimmer by Apichatpong by Patricio Guzman by Klaus Huettmann Weerasethakul The Edukators German co-producer: by Hans Weingartner Producer: German co-producer: CV Films/Berlin B & T Film/Berlin Thoke + Moebius Film/Berlin German producer: World Sales: y3/Berlin Celluloid Dreams/Paris World Sales: Celluloid Dreams/Paris Credits not contractual Co-Productions Cannes Film Festival Un Certain Regard Un Certain Regard Un Certain Regard Directors’ Fortnight Marseille Hotel Whisky Charlotte by Angela Schanelec by Jessica Hausner by Juan Pablo Rebella by Ulrike von Ribbeck & Pablo Stoll Producer: German co-producer: Producer: Schramm Film/Berlin Essential Film/Berlin German co-producer: Deutsche Film- & Fernseh- World Sales: Pandora Film/Cologne akademie (dffb)/Berlin The Coproduction Office/Paris World Sales: Bavaria Film International/ Geiselgasteig german films quarterly 2/2004 6 focus on 50 YEARS EXPORT-UNION OF GERMAN CINEMA 22 interview with Peter Dinges FULFILLING EXPECTATIONS directors’ portraits 24 THE VISIONARY A portrait of Achim von Borries 25 RISKING GREAT EMOTIONS A portrait of Vanessa Jopp 28 producers’ portrait FILMMAKING SHOULD BE FUN A portrait of Avista Film 30 actor’s portrait BORN TO ACT A portrait of Moritz Bleibtreu 32 news in production 38 BERGKRISTALL ROCK CRYSTAL Joseph Vilsmaier 38 DAS BLUT DER TEMPLER THE BLOOD OF THE TEMPLARS Florian Baxmeyer 39 BRUDERMORD FRATRICIDE Yilmaz Arslan 40 DIE DALTONS VS. -

Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: the Use of Films to Facilitate Dialogue." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Dissertations Department of Communication 5-3-2007 Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Use of Films ot Facilitate Dialogue Elana Shefrin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Shefrin, Elana, "Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Use of Films to Facilitate Dialogue." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss/14 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RE-MEDIATING THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT: THE USE OF FILMS TO FACILITATE DIALOGUE by ELANA SHEFRIN Under the Direction of M. Lane Bruner ABSTRACT With the objective of outlining a decision-making process for the selection, evaluation, and application of films for invigorating Palestinian-Israeli dialogue encounters, this project researches, collates, and weaves together the historico-political narratives of the Israeli- Palestinian conflict, the artistic worldviews of the Israeli and Palestinian national cinemas, and the procedural designs of successful Track II dialogue interventions. Using a tailored version of Lucien Goldman’s method of homologic textual analysis, three Palestinian and three Israeli popular film texts are analyzed along the dimensions of Historico-Political Contextuality, Socio- Cultural Intertextuality, and Ethno-National Textuality. Then, applying the six “best practices” criteria gleaned from thriving dialogue programs, coupled with the six “cautionary tales” criteria gleaned from flawed dialogue models, three bi-national peacebuilding film texts are homologically analyzed and contrasted with the six popular film texts. -

Semester Program Spring 2019

SCHOOL OF MEDIA ARTS Professor Angela Melitopoulos Artistic practice Critical reflection Knowledge-based teaching Exhibition practice CAKI entrepreneurship course for MFA 2nd year students (mandatory) SEMESTER PROGRAM - SPRING 2019 (February 1 – June 30) Mandatory DATE TIME TEACHING FEBRUARY Semester Graduating students (tutoring, meetings etc.) February 4 LAB COURSES February 5 LAB COURSES February 6 LAB COURSES February 7 LAB COURSES February 8 LAB COURSES February 12 10 - 17 CONTINUATION OF THE WORKSHOP, WHICH STARTED WITH DAY 1 AND 2 IN JANUARY DAY 3 Workshop with Kerstin Schroedinger: Narration and Material: seminar on artistic research methods Based on artistic research on colonial and neocolonial entanglements of the local textile industry, in the seminar we aim to disentangle the history of specific products (such as dyes, fabrics, clothes) and discuss their participation in such colonial structures (in chemistry, fashion, and others) and their global effects. We will document site visits to industrial sites, workshops, archives and collections and collect materials in sound, image, text and movement. With the collected material we create a mapping for a discursive discussion about the limitations of a national framework of historiography and memory politics. Tuesday January 15 10-13 uhr artist presentation Rainbow’s Gravity (Video, 2014, in collaboration with Mareike Bernien) and Bläue (installation 2017, video and 6-channel audio) with a focus on artistic research methods 14-17 uhr workshop 1 teil on Danish textile industry -

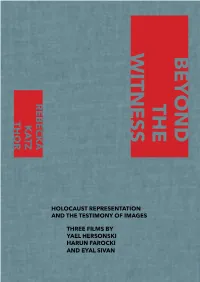

Holocaust Representations and the Testimony of Images

WI BEY T NESS O TH REBECKA REBECKA ND THOR KA E TZ HOLOCAUST REPRESENTATION AND THE TESTIMONY OF IMAGES THREE FILMS BY YAEL HERSONSKI HARUN FAROCKI AND EYAL SIVAN WITNESS BEYOND BEYOND T REBECKA REBECKA H T KAT H E O Z R HOLOCAUST REPRESENTATION AND THE TESTIMONY OF IMAGES THREE FILMS BY YAEL HERSONSKI HARUN FAROCKI EYAL SIVAN FOR SAM AND ISIDOR PRELUDE 1–3 9–13 WHAT IS A WITNESS? 15–23 AN EVENT WITHOUT AN IMAGE 23–24 WHEN NO WITNESSES ARE LEFT 24–28 IMPOSSIBLE REPRESENTATIONS 28–31 IMAGE AS WITNESS 32–36 GESTIC THINKING 36–39 RESITUATED IMAGES AND THE QUESTION OF FRAME 39–43 STILL IMAGES 45-69 BRESLAUER AT WORK IN WESTERBORK, 1944. 45 A FILM UNFINISHED BY YAEL HERSONSKI 46–55 RESPITE BY HARUN FAROCKI 56–63 THE SPECIALIST BY EYAL SIVAN 64–69 ARCHIVAL WORK 71–72 THE STATUS OF ARCHIVAL IMAGES 73–76 ARCHIVAL STORIES 1: DAS GHETTO AND A FILM UNFINISHED 76–80 ARCHIVAL STORIES 2: THE WESTERBORK MATERIAL AND RESPITE 80–83 ARCHIVAL STORIES 3: RECORDING THE EICHMANN TRIAL AND THE SPECIALIST 84–86 5 STRUCTURING FRAMES 87–88 AGENCY AND ANALYSIS 88–91 THE HOW OF THE IMAGE 91–95 OVERCOMING AESTHETIC DISTANCE 96–99 TRUTHS IN NON-TRUSTWORTHY IMAGES 100–104 REFLEXIVITY AND EXPOSURE 104–107 VOICE, TEXT, AND NARRATION 109–110 VERBAL AND PICTORIAL WITNESSING 110–115 SOUNDS OF SILENCE AND COMMOTION 115–117 SHOWING INSTEAD OF TELLING 117–119 VISUALIZING TESTIMONY 120–123 THE PERPETRATOR AS WITNESS 125–126 THE NAZI GAZE 126–129 THE PERPETRATOR IN FOCUS 129–132 REMOVING THE WITNESS 132–137 HAPPY IMAGES OF THE CAMP 137–141 THE TESTIMONY OF IMAGES 143–144 TESTIMONY -

Modern Palestinian Filmmaking in a Global World Sarah Frances Hudson University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2017 Modern Palestinian Filmmaking in a Global World Sarah Frances Hudson University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hudson, Sarah Frances, "Modern Palestinian Filmmaking in a Global World" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 1872. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1872 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Modern Palestinian Filmmaking in a Global World A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies by Sarah Hudson Hendrix College Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, 2007 University of Arkansas Master of Arts in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies, 2011 May 2017 University of Arkansas This thesis/dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council: ____________________________________________ Dr. Mohja Kahf Dissertation Director ____________________________________________ Dr. Ted Swedenburg Committee Member ____________________________________________ Dr. Keith Booker Committee Member Abstract This dissertation employs a comprehensive approach to analyze the cinematic accent of feature length, fictional Palestinian cinema and offers concrete criteria to define the genre of Palestinian fictional film that go beyond traditional, nation-centered approaches to defining films. Employing Arjun Appardurai’s concepts of financescapes, technoscapes, mediascapes, ethnoscapes, and ideoscapes, I analyze the filmic accent of six Palestinian filmmakers: Michel Khleifi, Rashid Masharawi, Ali Nassar, Elia Suleiman, Hany Abu Assad, and Annemarie Jacir. -

The Shoah on Screen – Representing Crimes Against Humanity Big Screen, Film-Makers Generally Have to Address the Key Question of Realism

Mémoi In attempting to portray the Holocaust and crimes against humanity on the The Shoah on screen – representing crimes against humanity big screen, film-makers generally have to address the key question of realism. This is both an ethical and an artistic issue. The full range of approaches has emember been adopted, covering documentaries and fiction, historical reconstructions such as Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List, depicting reality in all its details, and more symbolic films such as Roberto Benigni’s Life is beautiful. Some films have been very controversial, and it is important to understand why. Is cinema the best way of informing the younger generations about what moire took place, or should this perhaps be left, for example, to CD-Roms, videos Memoi or archive collections? What is the difference between these and the cinema as an art form? Is it possible to inform and appeal to the emotions without being explicit? Is emotion itself, though often very intense, not ambivalent? These are the questions addressed by this book which sets out to show that the cinema, a major art form today, cannot merely depict the horrors of concentration camps but must also nurture greater sensitivity among increas- Mémoire ingly younger audiences, inured by the many images of violence conveyed in the media. ireRemem moireRem The Shoah on screen – www.coe.int Representing crimes The Council of Europe has 47 member states, covering virtually the entire continent of Europe. It seeks to develop common democratic and legal princi- against humanity ples based on the European Convention on Human Rights and other reference texts on the protection of individuals.