AN ABSTRACT of the THESIS of Studies, Campus Climate, Extracurricular Activities, and Career Opportunities. Through

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View the Community Input Summary Series 1: Establishing a Common

Series 1: Establishing a Common Foundation July 2013 I ntroducti on This document presents a summary of responses from the first series of Plan Rapid City community engagement activities in July 2013. The series included the following community engagement events: • Leadership Worksessions (July 15 & 16) • Movie Under the Stars Booth (July 15) • Advisory Committee Meeting (July 16) • Teen Input Event (July 16) • Community Input Event (July 16) • Online Vision Survey (July) Each of the events included background information on the Comprehensive Plan process and a discussion of issues and opportunities related to the draft Community Profile. Leadership Worksession Meeting Notes – July 1 5, 201 3 10:45 am – 12:00 pm – City/School Administration Building Community Profile / Issues & Opportunities • Transportation inventory maps need to show the railroad more clearly (especially the Intermodal map – show using a railroad symbol) • Need a plan for adding sidewalks in key locations • Senior transportation • Affordable and workforce housing • Student housing (on campus/off-campus) • Civic Center expansion – economic impact of Civic Center, fiscal issues • Backfill/infill, reinvestment and redevelopment critical as the City grows • Need to address retrofitting/reusing old historic homes (especially converting homes along corridors to commercial and other uses) • An understanding of the costs of the City to provide services would be beneficial in decision- making (e.g., economic analysis of some sort) • Reinvestment will make the community healthier -

Gender and Race in the Making of Afro-Brazilian Heritage by Jamie Lee Andreson a Dissertation S

Mothers in the Family of Saints: Gender and Race in the Making of Afro-Brazilian Heritage by Jamie Lee Andreson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Paul Christopher Johnson, Chair Associate Professor Paulina Alberto Associate Professor Victoria Langland Associate Professor Gayle Rubin Jamie Lee Andreson [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-1305-1256 © Jamie Lee Andreson 2020 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to all the women of Candomblé, and to each person who facilitated my experiences in the terreiros. ii Acknowledgements Without a doubt, the most important people for the creation of this work are the women of Candomblé who have kept traditions alive in their communities for centuries. To them, I ask permission from my own lugar de fala (the place from which I speak). I am immensely grateful to every person who accepted me into religious spaces and homes, treated me with respect, offered me delicious food, good conversation, new ways of thinking and solidarity. My time at the Bate Folha Temple was particularly impactful as I became involved with the production of the documentary for their centennial celebrations in 2016. At the Bate Folha Temple I thank Dona Olga Conceição Cruz, the oldest living member of the family, Cícero Rodrigues Franco Lima, the current head priest, and my closest friend and colleague at the temple, Carla Nogueira. I am grateful to the Agência Experimental of FACOM (Department of Communications) at UFBA (the Federal University of Bahia), led by Professor Severino Beto, for including me in the documentary process. -

Farmers Consider 'Critter Pads' for Livestock

Drug Court Tax Meets Initial Expectations / Main 3 $1 Midweek Edition Thursday, May 3, 2012 Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com Payback W.F. West Avenges Lone Loss With EvCo Sweep at Rival Centralia / Sports 1 Prison Learn New Dogs Tricks Farmers Consider ‘Critter Pads’ for Livestock Chris Geier / [email protected] Above: Thurman Sherill, left, and Don Glaude exit their housing facility with Bodie, a black lab they are training to be a service dog in a new program at the Cedar Creek Owners minimum security prison in Littlerock. Top right: Inmates Cary Croy and Timothy Barnes, right, with Libby, a boxer-lab mix they are training to be a service dog in a new program at the Cedar Creek minimum Make Plans security prison in Littlerock. to Avoid By Adam Pearson “They get bored really quick,” Further [email protected] said Gibbs, whose 6-month-old Inmates Train black lab Abby is a prime candi- Livestock LITTLEROCK — The se- date to become a service dog one Loss from Pups as Service cret to training a dog to excel at day for an injured war veteran. commands more sophisticated “And when they do, it’s like talk- Flooding than parlor tricks is to work on ing to a wall, basically.” Dogs for Injured the canine for five to 10 minutes Gibbs and Larry Gregory, / Main 4 at a time and no more than four 45, who is serving time for first- times a day, says 37-year-old Ja- degree kidnapping and first-de- War Veterans son Gibbs, a Cedar Creek Cor- gree robbery out of Pierce Coun- rections Center inmate serving ty, share a cell with Abby. -

Hero for History

C M Y K SPLASHING As the weather warms up and you start to enjoy days SAFELY in the pool, remember safety comes first B1 s Art Uncorked offers EWS UN watercolor class B3 NHighlands County’s Hometown Newspaper-S Since 1927 75¢ The News-Sun s supports Child Abuse HCSO warning of Blue Streaks race to Prevention Month, which spring scams A5 win at home A10 starts April 1 www.newssun.com Sunday, March 30, 2014 SFSC Suspects softball linked to player ero for history 2nd home killed in H invasion crash BY PHIL ATTINGER Staff Writer Freshman Lauren Phillips one of 4 killed AVON PARK — Four people as- in head-on collision sociated with a home invasion in Lake Placid last December have News-Sun staff report been linked to a similar robbery in Avon Park at that same time, and AVON PARK — “She was an additional man has been iden- an angel that we didn’t tified as affiliated with them, ac- even know we had un- cording to arrest reports. til now. We took her for The Highlands County Sher- granted,” South Flori- iff’s Office has charged Victor Lee da State College softball Johnson, 20, of 164 Watson Ave. in player Kala Thompson West Orange, N.J., with robbery said about with a firearm, armed burglary of a her team- mate, Lau- SEE SUSPECTS | A9 ren Phil- Katara Simmons/News-Sun lips, who Carole Goad has been Sebring’s historian for 13 years. Her dedication to preserving the history of Se- was one of bring has earned her the News-Sun Unsung Hero award for March. -

Embodying Citizenship in Brazilian Women's Film, Video, And

Embodying Citizenship in Brazilian Women’s Film, Video, and Literature, 1971 to 1988 by Leslie Louise Marsh A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Romance Languages and Literatures: Spanish) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Catherine L. Benamou, Co-Chair Assistant Professor Lawrence M. La Fountain-Stokes, Co-Chair Associate Professor Sueann Caulfield Associate Professor Maria E. Cotera Assistant Professor Paulina Laura Alberto A catfish laughs. It thinks of other catfishes In other ponds. ⎯ Koi Nagata © Leslie Louise Marsh 2008 To my parents Linda and Larry Marsh, with love. To all those who helped and supported me in Brazil and To Catherine Benamou, whose patience is only one of her many virtues, my eternal gratitude. ii Table of Contents Dedication ii Abstract iv Chapter 1 Introduction 1 2 The Body and Citizenship in Clarice Lispector’s A 21 Via Crucis do Corpo (1974) and Sonia Coutinho’s Nascimento de uma Mulher (1971) 3 Comparative Perspectives on Brazilian Women’s 90 Filmmaking and the State during the 1970s and 1980s 4 Contesting the Boundaries of Belonging in the Early 156 Films of Ana Carolina Teixeira Soares and Tizuka Yamasaki 5 Reformulating Civitas in Brazil, 1980 to 1989 225 6 Technologies of Citizenship: Brazilian Women’s 254 Independent and Alternative Film and Video, 1983 to 1988 7 Conclusion 342 Sources Consulted 348 iii Abstract Embodying Citizenship in Brazilian Women’s Film, Video, and Literature, 1971 to 1988 by Leslie Louise Marsh Co-Chairs: Catherine L. Benamou and Lawrence M. -

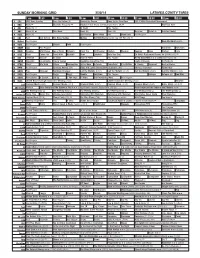

Sunday Morning Grid 3/30/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/30/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Behind the Dream Road to the Final Four 2014 NCAA Basketball Tournament 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Hockey Boston Bruins at Philadelphia Flyers. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. IndyCar Racing 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup: STP 500. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Rock My World (2009) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Iggy Paid Program Transform. Transform. 24 KVCR Painting Wild Places Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Kevin Kitchen Lidia 28 KCET Peep Curios -ity Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Train Your Dog Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program A Few Good Men ››› (1992) Tom Cruise. (R) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Tras la Verdad República Deportiva (TVG) Lupita D’Alessio Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Christ Win Walk Prince Redemption Active Word In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Supernat. Best of Praise 46 KFTR Paid Program Aventura Animal (TVY) Fluke ›› (1995, Drama) Matthew Modine. -

Thursday Morning, July 29

THURSDAY MORNING, JULY 29 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 VER COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest Who Wants to Be The View Actress Patricia Clark- Live With Regis and Kelly Actor 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) (cc) a Millionaire son. (N) (cc) (TV14) Michael Keaton. (N) (cc) KOIN Local 6 KOIN Local 6 The Early Show (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 Early at 6 (N) Early at 6:30 (N) (TV14) Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Critters; Rob Schneider; Flo Rida. (N) (cc) Rachael Ray (cc) (TVG) 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) Sit and Be Fit Between the Curious George Sid the Science Super Why! (cc) Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Elmo and Abby Clifford the Big Dragon Tales WordWorld (TVY) Martha Speaks 10/KOPB 10 10 (cc) (TVG) Lions (TVY) (TVY) Kid (cc) (TVY) (TVY) (TVY) must find an amphibian. (TVY) Red Dog (TVY) (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) The Bonnie Hunt Show Scott Wolf; Mid-Day Oregon Paid 12/KPTV 12 12 Kevin Federline. (TVPG) (N) Portland Public Affairs Paid Paid 3-2-1 Penguins! Willa’s Wild Life Through the Bible Zola Levitt Pres- Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 (cc) (TVY7) (TVY7) ents (TVG) Changing Your John Hagee Rod Parsley (cc) This Is Your Day Kenneth Cope- Unfolding Majesty Life Change Cafe John Bishop TV Behind the Against All Odds James Robison Marilyn Hickey 24/KNMT 20 20 World (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) land (TVG) (cc) Scenes (cc) (cc) (cc) (TVG) (cc) Just Shoot Me George Lopez Edgemont (cc) My Wife and Kids That ’70s Show The King of My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Are You Smarter? Are You Smarter? The Steve Wilkos Show Steve con- 32/KRCW 3 3 (cc) (TV14) (cc) (TVPG) (TVPG) (TVPG) Winter. -

The Suit Case PARIS — There’S an Elegant Mood Sweeping Through Fashion, and Karl Lagerfeld Caught It in His Fall Collection for Chanel

OSCARS GET WAR JITTERS/2 JAPAN’S LUXURY VIEW/12 WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • TheWEDNESDAY Retailers’ Daily Newspaper • March 12, 2003 Vol. 185, No. 51 $2.00 Sportswear The Suit Case PARIS — There’s an elegant mood sweeping through fashion, and Karl Lagerfeld caught it in his fall collection for Chanel. But elegance often comes with a twist these days, and the line was also au courant, this time with a bit of a Sixties and rock ’n’ roll spin. There were fab jackets, of course, shown with super-short skirts, sometimes with the addition of a little lace or fur. Here, one of the great-looking new Chanels that makes Karl’s case for suits. For more on the season, see pages 6 to 9. Retail’s Latest Worry: Rocketing Gas Prices Cost Shoppers Billions By David Moin NEW YORK — These days, when retailers say consumers are running out of gas, they mean it in more ways than one. With rising threats of domestic terrorism, the weak economy and the wicked winter, consumers have been beaten down. Now, soaring gas prices are fueling even more angst — and the result is that the economy is losing $1 billion in consumer expenditure for every penny increase in pump prices, according IANNONI G to estimates from Salomon Smith NNI A See Gas, Page13 IOV G Y B PHOTO 2 2003 WWDWEDNESDAY Sportswear 12, Beverly Hills Postpones GENERAL PARIS COLLECTIONS: Sonia Rykiel, Y-3, Cacharel and Martine Sitbon were MARCH , 6 among the highlights as the runway season drew to a close. Walk of Style Ceremony With war, terrorism and the weak economy weighing on consumers, 1 soaring gas prices are now taking more cash from them — and retailers. -

Language Revitalization, State Regulation, and Indigenous Identity in Urban Amazonia

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 11-8-2013 12:00 AM In the House of Transformation: Language Revitalization, State Regulation, and Indigenous Identity in Urban Amazonia Sarah A. Shulist The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Tania Granadillo The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Anthropology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Sarah A. Shulist 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Linguistic Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Shulist, Sarah A., "In the House of Transformation: Language Revitalization, State Regulation, and Indigenous Identity in Urban Amazonia" (2013). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1695. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1695 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN THE HOUSE OF TRANSFORMATION: LANGUAGE REVITALIZATION, STATE REGULATION, AND INDIGENOUS IDENTITY IN URBAN AMAZONIA (Thesis format: Monograph) by Sarah Shulist Graduate Program in Anthropology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Sarah Shulist 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines the practices surrounding advocacy for Indigenous language revitalization and maintenance in order to better understand the changing nature of of ethnolinguistic identity and the politics of culture in the Brazilian Amazon. Based on ethnographic fieldwork in the city of São Gabriel da Cachoeira, Amazonas, it specifically considers the complex challenges created for language revitalization activism among urban and diasporic Indigenous populations. -

Film Festival

Contemporary Arab Cinema Arabian2007 Sights FILMFESTIVAL October 26 – November 4 www.filmfestdc.org 2007Arabian Sights Contemporary Arab Cinema October 26 – November 4 www.filmfestdc.org presented by The Washington, DC International Film Festival The Twelfth Annual Arabian Sights Film Festival offers a dynamic and diverse range of new films from North Africa to Lebanon, Oman, Palestine and Saudi Arabia. Also featured this year are innovative selec- tions by Arab American filmmakers. Several directors will be present at their screenings to discuss their work. An Audience Award for favorite film will be presented. All films will be screened with English subtitles. Please visit www.filmfestdc.org for updates on films and guests. Admission Festival Pass $9.00 per person for each screen- A special package of 10 tickets is ing, unless otherwise noted. available online and at the theater for a discounted price of $81.00. Tickets for any film in the festival (This package does not include may be purchased online at the October 26 screening of www.filmfestdc.org and at the Caramel). theater starting one hour before the first show. Cash or check sales only at the theater. Locations AMC Loews Dupont Circle 5 Avalon Theatre All screenings will be held at this (Opening Film only) location except the opening film. 5612 Connecticut Ave., NW. 1350 19th St., NW. Take Metro Street parking available. Red Line to Dupont Circle, South exit. For More Information www.filmfestdc.org Parking available at garage opposite 202-724-5613 the theater on 19th St. for $10.00 after 5:45 pm with mention of Arabian Sights on Fridays and Saturdays only. -

Winona Daily News Winona City Newspapers

Winona State University OpenRiver Winona Daily News Winona City Newspapers 3-6-1973 Winona Daily News Winona Daily News Follow this and additional works at: https://openriver.winona.edu/winonadailynews Recommended Citation Winona Daily News, "Winona Daily News" (1973). Winona Daily News. 1214. https://openriver.winona.edu/winonadailynews/1214 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Winona City Newspapers at OpenRiver. It has been accepted for inclusion in Winona Daily News by an authorized administrator of OpenRiver. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CFoudy and mild ¦ l IT'S OUTA 1IOHT through Wednesday; I THI WAY WANT ADS Set Tilings Moving rain or snow t ^ Of Saigon s prisoners Cong asks more releases By GEORGE ESPER ers of war on , the list which the Paris when the cease-fire sonnel. agreement was signed Jan. 27. SAIGON (AP) -The Viet Saigon government handed The military commission an- Cong asked the Saigon govern- over in Paris?" Thu asked in He said the Saigon government his message. "Otherwise, what must turn over at least one- nounced, meanwhile, it agreed ment today to release one- of', fourth of the communist prison- is the exact number of military fourth the 26,734 military three days ago on a five-point ers it; holds and begin the sec- personnel which the Saigon prisoners on the list it sub- program to give North Viet- government will turn over to mitted in Paris. This would be namese and Viet Cong repre- ond phase of Vietnamese pris- Revolutionary oner exchanges immediately. -

EU Page 1 COVER.Indd

Eating Around the World in Jax • Wizarding World of Harry Potter • Local Art Collectors free monthly guide to entertainment & more | july 2010 | eujacksonville.com 2 JULY 2010 | eu jacksonville monthly contents JULY 2010 feature page 4-8 dining around the world join EU on facebook! dish page 9 organic shopping page 10 dish update + events page 11 queen of sheba restaurant review page 11 antojitos colombian bakery life + stuff follow us on twitter! page 12 family events page 12 on the river Look for @EUJacksonville and page 13 july 4th events on the cover page 14 have kid will travel @EU_Music where you The cover image is a variation of the original page 15 wizarding world of harry potter Music Video Revival poster design by Varick can get daily music and Rosete. Varick is a designer / illustrator page 16 local shopping entertainment updates and the current president of our local AIGA page 17 reading strange chapter. See page 25 to read about the Music Video Revival and page 21 to learn more about AIGA. arts + culture eu staff page 18 theatre & cultural events page 27 sound check managing director page 18 aurora black arts festival page 27 spotlight: wild life society Shelley Henley page 19 cinderella at the alhambra page 28 featured music events creative director page 20 why art matters page 29 album review: honey chamber Rachel Best Henley page 21 AIGA: part 4 - the boardroom & page 29 album review: dan sartain copy editors Kellie Abrahamson the business suit page 30-35 music events Erin Thursby page 22 collectors choice at the cummer