Alcohol Use and Suicidal Behavior Among Police Officers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suicide Research: Selected Readings. Volume 2

SuicideResearchText-Vol2:SuicideResearchText-Vol2 8/6/10 11:00 AM Page i SUICIDE RESEARCH: SELECTED READINGS Volume 2 May 2009–October 2009 J. Sveticic, K. Andersen, D. De Leo Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Suicide Prevention National Centre of Excellence in Suicide Prevention SuicideResearchText-Vol2:SuicideResearchText-Vol2 8/6/10 11:00 AM Page ii First published in 2009 Australian Academic Press 32 Jeays Street Bowen Hills Qld 4006 Australia www.australianacademicpress.com.au Reprinted in 2010 Copyright for the Introduction and Comments sections is held by the Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention, 2009. Copyright in all abstracts is retained by the current rights holder. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act, 1968, no part may be reproduced without prior permission from the Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention. ISBN: 978-1-921513-53-4 SuicideResearchText-Vol2:SuicideResearchText-Vol2 8/6/10 11:00 AM Page iii Contents Foreword ................................................................................................vii Acknowledgments ..............................................................................viii Introduction Context ..................................................................................................1 Methodology ........................................................................................2 Key articles Alexopoulos et al, 2009. Reducing suicidal ideation -

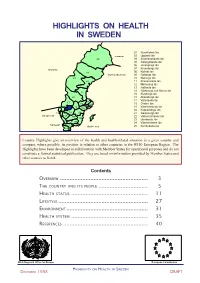

Sweden Part 1

HIGHLIGHTS ON HEALTH IN SWEDEN 01 Stockholms län 03 Uppsala län Finland 25 04 Södermanlands län 05 Östergötlands län 06 Jönköpings län 07 Kronobergs län Norway 08 Kalmar län 24 Gulf of Bothnia 09 Gotlands län 23 10 Blekinge län 22 11 Kristianstads län 12 Malmöhus län 13 Hallands län 14 Göteborgs och Bohus län 21 15 Älvsborgs län 20 16 Skaraborgs län 17 Värmlands län 17 03 18 Örebro län 19 01 18 19 Västmanlands län 04 20 Kopparbergs län 14 16 05 21 Gävleborgs län Skagerrak 15 06 22 Västernorrlands län 08 09 23 Jämtlands län 13 07 24 Västerbottens län Kattegat 11 10 Baltic sea 25 Norrbottens län 12 Country Highlights give an overview of the health and health-related situation in a given country and compare, where possible, its position in relation to other countries in the WHO European Region. The Highlights have been developed in collaboration with Member States for operational purposes and do not constitute a formal statistical publication. They are based on information provided by Member States and other sources as listed. Contents OVERVIEW ....................................................... 3 THE COUNTRY AND ITS PEOPLE ............................... 5 HEALTH STATUS ................................................ 11 LIFESTYLE ........................................................ 27 ENVIRONMENT ................................................... 31 HEALTH SYSTEM ................................................ 35 REFERENCES ..................................................... 40 WHO Regional Office for Europe European Commission -

Physician Suicide: a Scoping Literature Review to Highlight Opportunities for Prevention

GLOBAL PSYCHIATRY — Vol 3 | Issue 2 | 2020 Tiffany I. Leung, MD, MPH, FACP, FAMIA1*, Rebecca Snyder, MSIS2, Sima S. Pendharkar, MD, MPH, FACP3‡, Chwen-Yuen Angie Chen, MD, FACP, FASAM4‡ Physician Suicide: A Scoping Literature Review to Highlight Opportunities for Prevention 1Faculty of Health, Medicine, and Life Sciences, Department of Internal Medicine, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands 2Library Services, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA 3Division of Hospital Medicine, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Icahn School of Medicine Mt. Sinai, Brooklyn, NY, USA 4Department of Primary Care and Population Health, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, USA *email: [email protected] ‡Indicates equal contributions as last authors to the production of this manuscript. DOI: 10.2478/gp-2020-0014 Received: 27 February 2020; Accepted: 12 May 2020 Abstract Objective: The aim of this scoping review is to map the current landscape of published research and perspectives on physician suicide. Findings could serve as a roadmap for further investigations and potentially inform efforts to prevent physician suicide. Methods: Ovid MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Scopus were searched for English-language publications from August 21, 2017 through April 28, 2018. Inclusion criteria were a primary outcome or thesis focused on suicide (including suicide completion, attempts, and thoughts or ideation) among medical students, postgraduate trainees, or attending physicians. Opinion articles were included. Studies that were non-English or those that only mentioned physician burnout, mental health, or substance use disorders were excluded. Data extraction was performed by two authors. Results: The search yielded 1,596 articles, of which 347 articles passed to the full-text review round. -

Season of Birth in Suicidology

UMEÅ UNIVERSITY MEDICAL DISSERTATIONS New Series No. 604 ISSN 0346-6612 ISBN 91-7191-645-8. From the Division of Psychiatry, Department of Clinical Science, Umeå University, SE-901 85 Umeå, Sweden SEASON OF BIRTH IN SUICIDOLOGY Neurobiological and epidemiological studies Jayanti Chotai Umeå 1999 UMEÅ UNIVERSITY MEDICAL DISSERTATIONS New Series No. 604 ISSN 0346-6612 ISBN 91-7191-645-8. From the Division of Psychiatry, Department of Clinical Science, Umeå University, 901 85 Umeå, Sweden. SEASON OF BIRTH IN SUICIDOLOGY Neurobiological and epidemiological studies AKADEMISK AVHANDLING som med vederbörligt tillstånd av rektorsämbetet vid Umeå universitet for avläggande av medicine doktorsexamen kommer att offentligen försvaras i Sal B, 9 tr, Tandläkarhögskolan, Norrlands universitetssjukhus, Umeå, fredagen den 28 maj 1999, kl 13.00 av Jayanti Chotai 1 v. *5 <J> va Fak ultetsopponent: Professor Hans Ågren, Karolinska institutet, Sektionen för psykiatri, Huddinge sjukhus Dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Medical Science in Psychiatry presented at Umeå University in 1999. ABSTRACT Chotai J (1999). Season of birth in suicidology: neu robiologies and epidemiological studies. Umeå University, Department of Clinical Science, Division of Psychiatry, 901 85 Umeå, Sweden. ISSN 0346-6612 ISBN 91-7191-645-8. Barkpround: Several neuropsychiatrie disorders have shown season of birth associations. Low cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of the serotonin metabolite 5-HIAA and the dopamine metabolite HVA have been associated with suicidal behaviour, impulsivity, and aggression. This thesis investigated associations between the season of birth, the CSF levels of three monoamine metabolites (including MHPG of norepinephrine), the scales of the diagnostic interview for borderline patients (DIB), and psychiatric diagnoses. -

Preventing Suicide a Resource for General Physicians

WHO/MNH/MBD/00.1 Page 1 WHO/MNH/MBD/00.1 Original: English Distr.: General PREVENTING SUICIDE A RESOURCE FOR GENERAL PHYSICIANS This document is one of a series of resources addressed to specific social and professional groups particularly relevant to the prevention of suicide. It has been prepared as part of SUPRE, the WHO worldwide initiative for the prevention of suicide. Keywords: suicide / prevention / resources / general physicians / training / primary health care. Mental and Behavioural Disorders Department of Mental Health World Health Organization Geneva 2000 WHO/MNH/MBD/00.1 Page 2 © World Health Organization, 2000 This document is not a formal publication of the World Health Organization (WHO), and all rights are reserved by the Organization. The document may, however, be freely reviewed, abstracted, reproduced or translated, in part or in whole, but not for sale in conjunction with commercial purposes. The views expressed in documents by named authors are solely the responsibility of those authors. WHO/MNH/MBD/00.1 Page 3 CONTENTS Foreword.....................................................................................................................................4 The burden of suicide.................................................................................................................5 Suicide and mental disorders.....................................................................................................5 Suicide and physical disorders...................................................................................................8 -

Marriage and Suicide: Recent Trends and an Investigation of the Possible Restraining Effects of Dependent Children

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1976 Marriage and Suicide: Recent Trends and an Investigation of the Possible Restraining Effects of Dependent Children Conrad M. Kozak Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Kozak, Conrad M., "Marriage and Suicide: Recent Trends and an Investigation of the Possible Restraining Effects of Dependent Children" (1976). Master's Theses. 2935. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/2935 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1976 Conrad M. Kozak MARRIAGE AND SUICIDE: RECENT TRENDS AND AN INVESTIGATION OF THE POSSIBLE RESTRAINING EFFECTS OF DEPENDENT CHILDREN by Conrad Kozak A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts May 1976 ACKNOWLEDGHENTS The author would sincerely like to thank the Cook County Coroner, Dr. Andrew Toman, as well as his fine staff, Mr. James Walsh, Mrs. Edna Toma and Mr. Ted Banker, Jr. for their helpful aid and cooperation in this project. Without them this study could not have taken place. Thanks and gratitude are also extended to Dr. James 0. Gibbs and Dr. Edward M. -

Seasonality of Suicidal Behavior

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 531-547; doi:10.3390/ijerph9020531 OPEN ACCESS International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health ISSN 1660-4601 www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph Review Seasonality of Suicidal Behavior Jong-Min Woo 1,2, Olaoluwa Okusaga 3,4 and Teodor T. Postolache 3,4,* 1 Department of Psychiatry, Seoul Paik Hospital, Inje University School of Medicine, Mareunnae-ro 9, Jung-gu, Seoul, 100032, Korea; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Stress Research Institute, Inje University, 607 Obang-dong, Gimhae, Gyungnam, 621749, Korea 3 Psychiatry Residency Training Program, St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, 1100 Alabama Avenue, Washington, DC 20032, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Mood and Anxiety Program (MAP), Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]. Received: 16 December 2011; in revised form: 11 January 2012 / Accepted: 26 January 2012 / Published: 14 February 2012 Abstract: A seasonal suicide peak in spring is highly replicated, but its specific cause is unknown. We reviewed the literature on suicide risk factors which can be associated with seasonal variation of suicide rates, assessing published articles from 1979 to 2011. Such risk factors include environmental determinants, including physical, chemical, and biological factors. We also summarized the influence of potential demographic and clinical characteristics such as age, gender, month of birth, socioeconomic status, methods of prior suicide attempt, and comorbid psychiatric and medical diseases. Comprehensive evaluation of risk factors which could be linked to the seasonal variation in suicide is important, not only to identify the major driving force for the seasonality of suicide, but also could lead to better suicide prevention in general. -

Suicide Seasonality

Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 1383 Suicide Seasonality Theoretical and Clinical Implications GEORGIOS MAKRIS ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS ISSN 1651-6206 ISBN 978-91-513-0108-2 UPPSALA urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-330907 2017 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Gunnesalen, Ing 10, Akademiska sjukhuset, Uppsala, Thursday, 7 December 2017 at 13:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Faculty of Medicine). The examination will be conducted in Swedish. Faculty examiner: Professor Emeritus Hans Ågren (Institution för Neurovetenskap och fysiologi, Göteborg Universitet). Abstract Makris, G. 2017. Suicide Seasonality. Theoretical and Clinical Implications. Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 1383. 74 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-513-0108-2. Background: Although suicide seasonality has been well-documented, surprisingly little is known about its underlying mechanisms. Methods: In this thesis, data from three Swedish registers (Cause of Death Register, National Patient Register, Prescribed Drugs Register) and data from the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute were used. In Study I, the amplitude of suicide seasonality was estimated in completed suicides in 1992-2003 in individuals with different antidepressant medications or without antidepressants. In Study II, monthly suicide and sunshine data from 1992-2003 were used to examine the association between suicide and sunshine in groups with and without antidepressants. In Study III, the relationship between season of initiation of antidepressant treatment and the risk of suicidal behavior was explored in patients with a new treatment episode with antidepressant medication. In Study IV, the complex association between sunshine, temperature and suicidal behavior was investigated in patients with a new treatment episode with an antidepressant in two exposure windows (1-4 and 5-8 weeks) before the event. -

Physician Suicide: a Scoping Literature Review to Highlight Opportunities for Prevention

GLOBAL PSYCHIATRY — Vol 3 | Issue 2 | 2020 Tiffany I. Leung, MD, MPH, FACP, FAMIA1*, Rebecca Snyder, MSIS2, Sima S. Pendharkar, MD, MPH, FACP3‡, Chwen-Yuen Angie Chen, MD, FACP, FASAM4‡ Physician Suicide: A Scoping Literature Review to Highlight Opportunities for Prevention 1Faculty of Health, Medicine, and Life Sciences, Department of Internal Medicine, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands 2Library Services, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA 3Division of Hospital Medicine, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Icahn School of Medicine Mt. Sinai, Brooklyn, NY, USA 4Department of Primary Care and Population Health, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, USA *email: [email protected] ‡Indicates equal contributions as last authors to the production of this manuscript. DOI: 10.2478/gp-2020-0014 Received: 27 February 2020; Accepted: 12 May 2020 Abstract Objective: The aim of this scoping review is to map the current landscape of published research and perspectives on physician suicide. Findings could serve as a roadmap for further investigations and potentially inform efforts to prevent physician suicide. Methods: Ovid MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Scopus were searched for English-language publications from August 21, 2017 through April 28, 2018. Inclusion criteria were a primary outcome or thesis focused on suicide (including suicide completion, attempts, and thoughts or ideation) among medical students, postgraduate trainees, or attending physicians. Opinion articles were included. Studies that were non-English or those that only mentioned physician burnout, mental health, or substance use disorders were excluded. Data extraction was performed by two authors. Results: The search yielded 1,596 articles, of which 347 articles passed to the full-text review round. -

Suicidal Behaviour in Some Human Service Occupations with Special Emphasis on Physicians and Police

SUICIDAL BEHAVIOUR IN SOME HUMAN SERVICE OCCUPATIONS WITH SPECIAL EMPHASIS ON PHYSICIANS AND POLICE A nationwide study Erlend Hem Department of Behavioural Sciences in Medicine Department Group of Basic Medical Sciences Faculty of Medicine University of Oslo Oslo 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 6 PREFACE 7 LIST OF PAPERS 10 1 INTRODUCTION 11 1.1 Suicide – a major health problem 11 1.2 Suicidal behaviour 12 1.3 Suicidal process 13 1.4 Human service occupations 15 2 BACKGROUND 16 2.1 Prevalence studies 16 2.2 Suicidal behaviour and occupation 17 2.2.1 Physicians 18 2.2.1.2 History 19 2.2.1.3 Review 20 2.2.1.3 Different specialities 21 2.2.1.4 Trends 22 2.2.1.5 Other studies 22 2.2.2 Dentists 23 2.2.3 Nurses 24 2.2.4 Police 26 2.2.5 Theologians 26 2.3 Research questions 27 3 MATERIAL AND METHODS 28 3.1 Materials 28 3.1.1 Paper I: Physicians 28 3.1.2 Paper II: Police 30 3.1.3 Paper III: Medical students and young physicians 31 3.1.4 Paper IV: Literature review 31 1 3.1.5 Paper V: Human service occupations 32 3.2 Methods 33 3.2.1 Design of studies 33 3.2.2 Variables 33 3.2.3 Description of variables 34 4 SUMMARY OF RESULTS 43 4.1 Paper I 43 4.2 Paper II 44 4.3 Paper III 45 4.4 Paper IV 46 4.5 Paper V 47 5 DISCUSSION 5.1. -

Seasonal Variations in Temperature–Suicide Associations Across South Korea

OCTOBER 2019 K A L K S T E I N E T A L . 731 Seasonal Variations in Temperature–Suicide Associations across South Korea a ADAM J. KALKSTEIN Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel MILOSLAV BELORID Applied Meteorology Research Division, National Institute of Meteorological Sciences, Seogwipo, Jeju, South Korea P. GRADY DIXON Department of Geosciences, Fort Hays State University, Hays, Kansas KYU RANG KIM Applied Meteorology Research Division, National Institute of Meteorological Sciences, Seogwipo, Jeju, South Korea KEITH A. BREMER Department of Geosciences, Fort Hays State University, Hays, Kansas (Manuscript received 31 January 2019, in final form 14 June 2019) ABSTRACT South Korea has among the highest rates of suicide in the world, and previous research suggests that suicide frequency increases with anomalously high temperatures, possibly as a result of increased sunshine. However, it is unclear whether this temperature–suicide association exists throughout the entire year. Using distrib- uted lag nonlinear modeling, which effectively controls for nonlinear and delayed effects, we examine temperature–suicide associations for both a warm season (April–September) and a cool season (October– March) for three cities across South Korea: Seoul, Daegu, and Busan. We find consistent, statistically sig- nificant, mostly linear relationships between relative risk of suicide and daily temperature in the cool season but few associations in the warm season. This seasonal signal of statistically significant temperature–suicide asso- ciations only in the cool season exists among all age segments, but especially for those 35 and older, along with both males and females. We further use distributed lag nonlinear modeling to examine cloud cover–suicide associations and find few significant relationships. -

Physician Assisted Suicide - Ethically Defendable Or Not? a Qualitative Ethical Analysis

Örebro University School of medicine Degree project, 30 ECTS May 2019 Physician Assisted Suicide - Ethically Defendable or Not? A Qualitative Ethical Analysis Version 2 Author: Maria Vangouver, MB School of Medical Sciences Örebro University Örebro Sweden Supervisor: Rolf Ahlzén MD, BA, PhD Region Värmland Karlstad Sweden Word count: Abstract: 247 Manuscript: 7115 Abstract Introduction: Physician assisted suicide (PAS) is the process where the patient terminates his/her life with the aid of a physician who provides a prescription for lethal medication that the patient self-administers in order to commit suicide. PAS is practiced in several countries and is now gaining support in Sweden. The debate shows some confusion regarding the definition of concepts and raises several ethical concerns. Aim: § To provide an empirical background and clarify concepts. § To analyze the ethical arguments for and against PAS. § To investigate relevant ethical differences between PAS, euthanasia and withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment. Materials and methods: Qualitative literature study based on argumentative- and conceptual analysis on hermeneutic ground. Materials were gathered through a literature search and consist of scientific articles, debate articles and official materials. Results: The main ethical arguments supporting PAS are autonomy, beneficence and dignity. PAS is by supporters seen as an act of compassion, which fulfills the physician’s obligation of non-abandonment. Opponents emphasize that PAS goes against the duty of beneficence and nonmaleficence and fear that there may be a slippery slope where more and more people will demand PAS. Conclusion: There is no consensus on whether PAS is considered ethically defendable or not. PAS appears to involve a conflict of interest between the principles of beneficence and autonomy.