Full List of Exhibit Artifacts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heroes of the Colored Race by Terry Ann Wildman Grade Level

Lesson Plan #2 for the Genius of Freedom: Heroes of the Colored Race by Terry Ann Wildman Grade Level: Upper elementary or middle school Topics: African American leaders Pennsylvania History Standards: 8.1.6 B, 8.2.9 A, 8.3.9 A Pennsylvania Core Standards: 8.5.6-8 A African American History, Prentice Hall textbook: N/A Overview: What is a hero? What defines a hero in one’s culture may be different throughout time and place. Getting our students to think about what constitutes a hero yesterday and today is the focus of this lesson. In the lithograph Heroes of the Colored Race there are three main figures and eight smaller ones. Students will explore who these figures are, why they were placed on the picture in this way, and the background images of life in America in the 1800s. Students will brainstorm and choose heroes of the African American people today and design a similar poster. Materials: Heroes of the Colored Race, Philadelphia, 1881. Biography cards of the 11 figures in the image (attached, to be printed out double-sided) Smartboard, whiteboard, or blackboard Computer access for students Poster board Chart Paper Markers Colored pencils Procedure: 1. Introduce the lesson with images of modern superheroes. Ask students to discuss why these figures are heroes. Decide on a working definition of a hero. Note these qualities on chart paper and display throughout the lesson. 2. Present the image Heroes of the Colored Race on the board. Ask what historic figures students recognize and begin to list those on the board. -

Reconstruction 1863–1877

11926_18_ch17_p458 11/18/10 12:45 PM Page 458 C h m a 17 p o c t . e Hear the Audio b r a 1 l 7 y a or t ist www.myh Reconstruction 1863–1877 CHAPTER OUTLINE American Communities 459 The Election of 1868 White Resistance and “Redemption” Hale County, Alabama: From Slavery to Woman Suffrage and Reconstruction King Cotton: Sharecroppers,Tenants,and the Southern Environment Freedom in a Black Belt Community The Meaning of Freedom 469 Moving About Reconstructing the North 482 The Politics of Reconstruction 461 African American Families, Churches, The Age of Capital The Defeated South and Schools Liberal Republicans and the Election Abraham Lincoln’s Plan Land and Labor After Slavery of 1872 Andrew Johnson and Presidential The Origins of African American Politics The Depression of 1873 Reconstruction The Electoral Crisis of 1876 Free Labor and the Radical Southern Politics and Society 476 RepublicanVision Southern Republicans Congressional Reconstruction and the Reconstructing the States:A Impeachment Crisis Mixed Record 11926_18_ch17_p459-489 11/18/10 12:45 PM Page 459 Theodor Kaufmann (1814–1896), On to Liberty, 1867. Oil on canvas, 36 ϫ 56 in (91.4 ϫ 142.2 cm). Runaway slaves escaping through the woods. Art Resource/Metropolitan Museum of Art. Hale County, Alabama: From Slavery to Freedom in a Black Belt Community n a bright Saturday morning in May 1867, had recently been O4,000 former slaves streamed into the town of appointed a voter Greensboro, bustling seat of Hale County in west- registrar for the dis- central Alabama.They came to hear speeches from two trict. -

©2013 Luis-Alejandro Dinnella-Borrego ALL RIGHTS

©2013 Luis-Alejandro Dinnella-Borrego ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “THAT OUR GOVERNMENT MAY STAND”: AFRICAN AMERICAN POLITICS IN THE POSTBELLUM SOUTH, 1865-1901 By LUIS-ALEJANDRO DINNELLA-BORREGO A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Mia Bay and Ann Fabian and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “That Our Government May Stand”: African American Politics in the Postbellum South, 1865-1913 by LUIS-ALEJANDRO DINNELLA-BORREGO Dissertation Director: Mia Bay and Ann Fabian This dissertation provides a fresh examination of black politics in the post-Civil War South by focusing on the careers of six black congressmen after the Civil War: John Mercer Langston of Virginia, James Thomas Rapier of Alabama, Robert Smalls of South Carolina, John Roy Lynch of Mississippi, Josiah Thomas Walls of Florida, and George Henry White of North Carolina. It examines the career trajectories, rhetoric, and policy agendas of these congressmen in order to determine how effectively they represented the wants and needs of the black electorate. The dissertation argues that black congressmen effectively represented and articulated the interests of their constituents. They did so by embracing a policy agenda favoring strong civil rights protections and encompassing a broad vision of economic modernization and expanded access for education. Furthermore, black congressmen embraced their role as national leaders and as spokesmen not only for their congressional districts and states, but for all African Americans throughout the South. -

The Most Complete Political Machine Ever Known: the North’S Union Leagues in the American Civil War

Civil War Book Review Spring 2019 Article 10 The Most Complete Political Machine Ever Known: The North’s Union Leagues in the American Civil War Timothy Wesley Austin Peay State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Wesley, Timothy (2019) "The Most Complete Political Machine Ever Known: The North’s Union Leagues in the American Civil War," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 21 : Iss. 2 . DOI: 10.31390/cwbr.21.2.10 Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol21/iss2/10 Wesley: The Most Complete Political Machine Ever Known: The North’s Union Review Wesley, Timothy Spring 2019 Taylor, Paul. The Most Complete Political Machine Ever Known: The North’s Union Leagues in the American Civil War. Kent State University Press, $45.00 ISBN 9781606353530 Paul Taylor’s The Most Complete Political Machine Ever Known: The North’s Union Leagues in the American Civil War reestablishes the significance of an underappreciated force in America’s political past. Once celebrated roundly for their contributions to Union victory, Union Leaguers have faded somewhat from our collective national memory. However understandable such amnesia might be given the trend of historians in recent decades to question the significance of everyday politics in the lives of wartime northerners, it is nevertheless unfortunate. Indeed, Taylor argues that the collective effect of the Union Leaguers on wartime Northern politics and the broader home front was anything but unimportant or inconsequential. Rooted in the broader culture of benevolent, fraternal, and secretive societies that characterized the age, the Union League movement was all but predictable. -

Civil War and Reconstruction Exhibit to Have Permanent Home at National Constitution Center, Beginning May 9, 2019

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Annie Stone, 215-409-6687 Merissa Blum, 215-409-6645 [email protected] [email protected] CIVIL WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION EXHIBIT TO HAVE PERMANENT HOME AT NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER, BEGINNING MAY 9, 2019 Civil War and Reconstruction: The Battle for Freedom and Equality will explore constitutional debates at the heart of the Second Founding, as well as the formation, passage, and impact of the Reconstruction Amendments Philadelphia, PA (January 31, 2019) – On May 9, 2019, the National Constitution Center’s new permanent exhibit—the first in America devoted to exploring the constitutional debates from the Civil War and Reconstruction—will open to the public. The exhibit will feature key figures central to the era— from Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass to John Bingham and Harriet Tubman—and will allow visitors of all ages to learn how the equality promised in the Declaration of Independence was finally inscribed in the Constitution by the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, collectively known as the Reconstruction Amendments. The 3,000-square-foot exhibit, entitled Civil War and Reconstruction: The Battle for Freedom and Equality, will feature over 100 artifacts, including original copies of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, Dred Scott’s signed petition for freedom, a pike purchased by John Brown for an armed raid to free enslaved people, a fragment of the flag that Abraham Lincoln raised at Independence Hall in 1861, and a ballot box marked “colored” from Virginia’s first statewide election that allowed black men to vote in 1867. The exhibit will also feature artifacts from the Civil War Museum of Philadelphia—one of the most significant Civil War collections in the country—housed at and on loan from the Gettysburg Foundation and The Union League of Philadelphia. -

Hiram Rhodes Revels 1827–1901

FORMER MEMBERS H 1870–1887 ������������������������������������������������������������������������ Hiram Rhodes Revels 1827–1901 UNITED STATES SENATOR H 1870–1871 REPUBLICAN FROM MIssIssIPPI freedman his entire life, Hiram Rhodes Revels was the in Indiana, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, and Tennessee. A first African American to serve in the U.S. Congress. Although Missouri forbade free blacks to live in the state With his moderate political orientation and oratorical skills for fear they would instigate uprisings, Revels took a honed from years as a preacher, Revels filled a vacant seat pastorate at an AME Church in St. Louis in 1853, noting in the United States Senate in 1870. Just before the Senate that the law was “seldom enforced.” However, Revels later agreed to admit a black man to its ranks on February 25, revealed he had to be careful because of restrictions on his Republican Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts movements. “I sedulously refrained from doing anything sized up the importance of the moment: “All men are that would incite slaves to run away from their masters,” he created equal, says the great Declaration,” Sumner roared, recalled. “It being understood that my object was to preach “and now a great act attests this verity. Today we make the the gospel to them, and improve their moral and spiritual Declaration a reality. The Declaration was only half condition even slave holders were tolerant of me.”5 Despite established by Independence. The greatest duty remained his cautiousness, Revels was imprisoned for preaching behind. In assuring the equal rights of all we complete to the black community in 1854. -

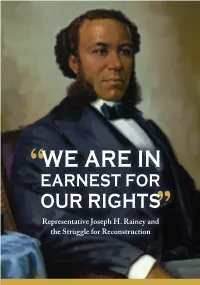

"We Are in Earnest for Our Rights": Representative

Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction On the cover: This portrait of Joseph Hayne Rainey, the f irst African American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, was unveiled in 2005. It hangs in the Capitol. Joseph Hayne Rainey, Simmie Knox, 2004, Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction September 2020 2 | “We Are in Earnest for Our Rights” n April 29, 1874, Joseph Hayne Rainey captivity and abolitionists such as Frederick of South Carolina arrived at the U.S. Douglass had long envisioned a day when OCapitol for the start of another legislative day. African Americans would wield power in the Born into slavery, Rainey had become the f irst halls of government. In fact, in 1855, almost African-American Member of the U.S. House 20 years before Rainey presided over the of Representatives when he was sworn in on House, John Mercer Langston—a future U.S. December 12, 1870. In less than four years, he Representative from Virginia—became one of had established himself as a skilled orator and the f irst Black of f iceholders in the United States respected colleague in Congress. upon his election as clerk of Brownhelm, Ohio. Rainey was dressed in a f ine suit and a blue silk But the fact remains that as a Black man in South tie as he took his seat in the back of the chamber Carolina, Joseph Rainey’s trailblazing career in to prepare for the upcoming debate on a American politics was an impossibility before the government funding bill. -

Influential African Americans in History

Influential African Americans in History Directions: Match the number with the correct name and description. The first five people to complete will receive a prize courtesy of The City of Olivette. To be eligible, send your completed worksheet to Kiana Fleming, Communications Manager, at [email protected]. __ Ta-Nehisi Coates is an American author and journalist. Coates gained a wide readership during his time as national correspondent at The Atlantic, where he wrote about cultural, social, and political issues, particularly regarding African Americans and white supremacy. __ Ella Baker was an essential activist during the civil rights movement. She was a field secretary and branch director for the NAACP, a key organizer for Martin Luther King Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and was heavily involved in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). SNCC prioritized nonviolent protest, assisted in organizing the 1961 Freedom Rides, and aided in registering Black voters. The Ella Baker Center for Human Rights exists today to carry on her legacy. __ Ernest Davis was an American football player, a halfback who won the Heisman Trophy in 1961 and was its first African-American recipient. Davis played college football for Syracuse University and was the first pick in the 1962 NFL Draft, where he was selected by the Cleveland Browns. __ In 1986, Patricia Bath, an ophthalmologist and laser scientist, invented laserphaco—a device and technique used to remove cataracts and revive patients' eyesight. It is now used internationally. __ Charles Richard Drew, dubbed the "Father of the Blood Bank" by the American Chemical Society, pioneered the research used to discover the effective long-term preservation of blood plasma. -

In 1848 the Slave-Turned-Abolitionist Frederick Douglass Wrote In

The Union LeagUe, BLack Leaders, and The recrUiTmenT of PhiLadeLPhia’s african american civiL War regimenTs Andrew T. Tremel n 1848 the slave-turned-abolitionist Frederick Douglass wrote in Ithe National Anti-Slavery Standard newspaper that Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, “more than any other [city] in our land, holds the destiny of our people.”1 Yet Douglass was also one of the biggest critics of the city’s treatment of its black citizens. He penned a censure in 1862: “There is not perhaps anywhere to be found a city in which prejudice against color is more rampant than Philadelphia.”2 There were a number of other critics. On March 4, 1863, the Christian Recorder, the official organ of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, commented after race riots in Detroit, “Even here, in the city of Philadelphia, in many places it is almost impossible for a respectable colored per- son to walk the streets without being assaulted.”3 To be sure, Philadelphia’s early residents showed some mod- erate sympathy with black citizens, especially through the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, but as the nineteenth century progressed, Philadelphia witnessed increased racial tension and a number of riots. In 1848 Douglass wrote in response to these pennsylvania history: a journal of mid-atlantic studies, vol. 80, no. 1, 2013. Copyright © 2013 The Pennsylvania Historical Association This content downloaded from 128.118.152.206 on Wed, 09 Jan 2019 20:56:18 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms pennsylvania history attitudes, “The Philadelphians were apathetic and neglectful of their duty to the black community as a whole.” The 1850s became a period of adjustment for the antislavery movement. -

Hiram Revels—The First African American Senator Hiram Rhodes Revels Was Born in North Carolina in the Year 11 1827

Comprehension and Fluency Name Read the passage. Use the ask and answer questions strategy to help you understand the text. Hiram Revels—The First African American Senator Hiram Rhodes Revels was born in North Carolina in the year 11 1827. Through his whole life he was a good citizen. He was a 24 great leader. He was highly respected. Revels became the first 34 African American to serve in the U.S. Senate. 42 A Hard Time for African Americans 48 Revels was born during a hard time for African Americans. 58 African Americans were treated badly. Most African Americans 66 in the South were enslaved. But Revels grew up as a free African 79 American, or freedman. This meant he could make his own 89 choices. 90 Still, the laws in the South were unfair. African Americans 100 had to work hard jobs. They were not allowed to go to school. 113 Though it was not legal, some freedmen ran schools for African 124 American children. As a child, Revels went to one of these 135 schools. But he was unable to go to college in the South. So he 149 left home to go to college in the North. Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 158 Preaching and Teaching 161 After college, Revels became the pastor of a church. He was 172 a good speaker. He was also a great teacher. He travelled all over 185 the country. He taught fellow African Americans. He knew that 195 this would make them good citizens. Practice • Grade 3 • Unit 5 • Week 4 233 Comprehension and Fluency Name The First African American Senator Revels moved to Natchez, Mississippi in 1866. -

Juneteenth Timeline Compiled and Edited by James Elton Johnson April, 2021

Annotated Juneteenth Timeline compiled and edited by James Elton Johnson April, 2021 The Juneteenth holiday is a uniquely American commemoration that is rooted in the Civil War. With an emphasis on southern New Jersey, this timeline is constructed from a regional perspective of metropolitan Philadelphia. 1860 November 6 Abraham Lincoln elected president December 18 The Crittenden Compromise is proposed by Kentucky Senator John J. Crittenden. This proposed legislation would have extended the Missouri Compromise line (36o 30’ latitude north) to the Pacific Ocean. Both Republicans and Democrats opposed this plan. Republicans were concerned about the territories being open tto slavery and unfair competition for white workers. Democrats were against any restriction on slavery in the territories. December 20 South Carolina secedes. President James Buchannan fails to act. 1861 January 9 Mississippi secedes January 10 Florida secedes January 11 Alabama secedes January 19 Georgia secedes January 26 Louisiana secedes February 1 Texas secedes March 4 Lincoln is inaugurated March 21 The Corvin amendment (below) is passed by Congress and submitted to the states for ratification. If ratified, this proposed 13th amendment would have explicitly enshrined the system of slavery into the U.S. Constitution. No amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will authorize or give to Congress the power to abolish or interfere, within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service by the laws of said State. 2 But for the outbreak of war, ratification of the Corvin amendment by the states was quite likely. Introduced in the Senate by William H. -

Union League Club

THE 2 61 4 75; UN IO N L EA G UE C L UB NEW YO RK HOUSE FIFTH AVENUE CORNER or EA T THIRTY-NINTH TREET , S S MDCCCLXXXVII Or a z uar 6 1 86 . g ni ed Febr y , 3 o ora ar 1 6 1 86 . Inc rp ted Febru y , 5 - No 2 6 as tr l o s . C ub H u e , E t Seventeenth S eet , M 1 2 1 86 O a . pened y , 3 - w -s x o s a so cor. as e Club H u e, M di n Avenue , E t T enty i th Stre t , O r I 1 868 . pened Ap il , - - o s cor. t tr t Club H u e, Fifth Avenue , Thir y ninth S ee . O a 1 88 1 . pened M rch 5, Press of ' P POTHM S ons G . S New York grzsiaznts. R BERT B MINTURN O . JONATHAN STURG ES CHARLES H MARSHALL . JOHN JAY 1 866 to KS 3 S UL Z JAC ON . CH T WILLIAM H PPIN J . O SEPH H CH ATE JO . O JOHN JAY GEORG E CABOT WARD HAMILTON FISH WILLIAM MEVARTS . CHA NCEY MDEPEW U . O fftzm for 1 8 8 7 . DE T P RE SI N . CHAUNCEY M . DEPEW . V -P DE N TS I CE RE SI . L G . O O . O E RAND B CANN N , J SMEPH W H WE , O . C RNELIUS N BLISS , JA ES C CARTER , VERMILYE H L O . JAC B D , MARS AL B BLAKE , G .