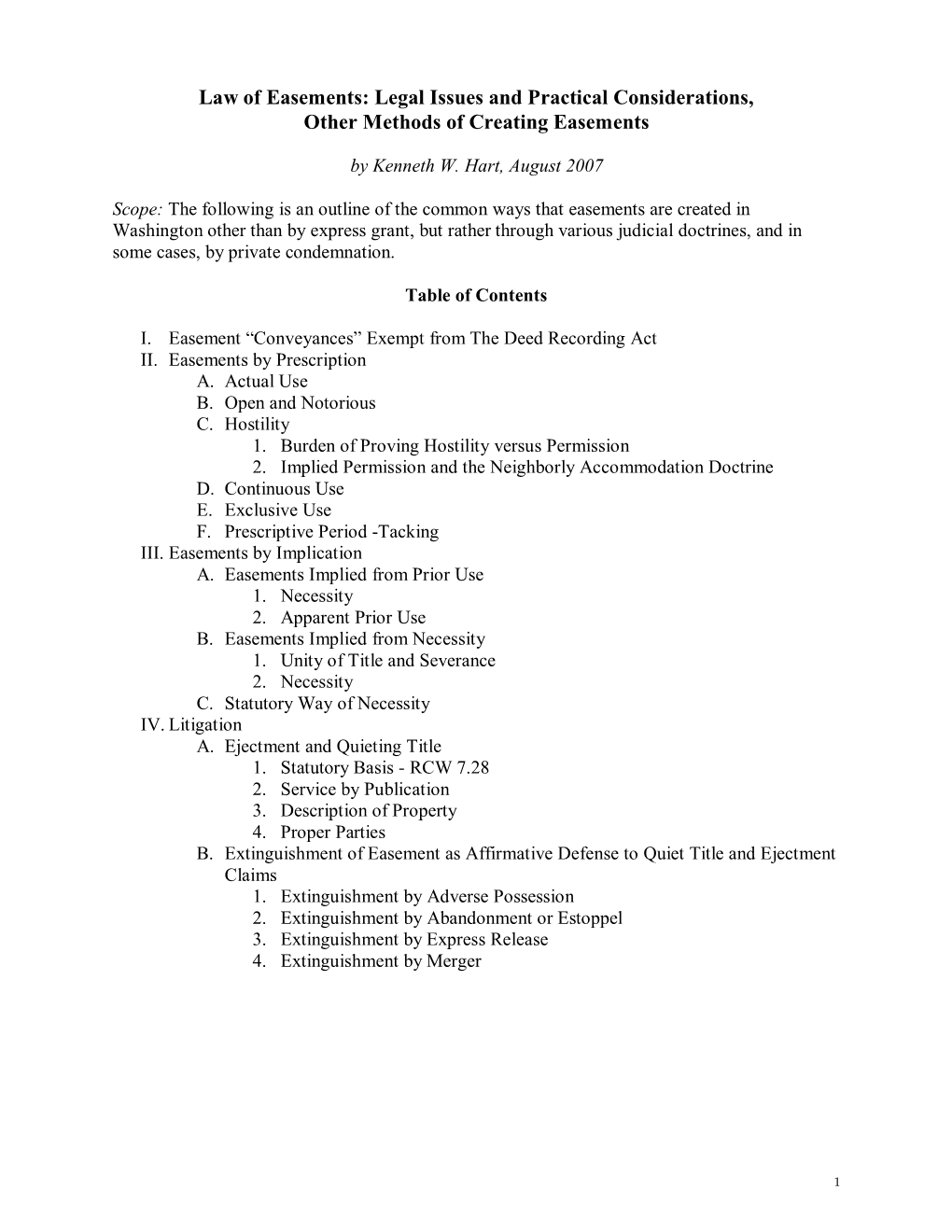

Law of Easements: Legal Issues and Practical Considerations, Other Methods of Creating Easements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk

Federal Trade Commission ftc.gov The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk Buying a home can be exciting. It also can be somewhat daunting, even if you’ve done it before. You will deal with mortgage options, credit reports, loan applications, contracts, points, appraisals, change orders, inspections, warranties, walk-throughs, settlement sheets, escrow accounts, recording fees, insurance, taxes...the list goes on. No doubt you will hear and see words and terms you’ve never heard before. Just what do they all mean? The Federal Trade Commission, the agency that promotes competition and protects consumers, has prepared this glossary to help you better understand the terms commonly used in the real estate and mortgage marketplace. A Annual Percentage Rate (APR): The cost of Appraisal: A professional analysis used a loan or other financing as an annual rate. to estimate the value of the property. This The APR includes the interest rate, points, includes examples of sales of similar prop- broker fees and certain other credit charges erties. a borrower is required to pay. Appraiser: A professional who conducts an Annuity: An amount paid yearly or at other analysis of the property, including examples regular intervals, often at a guaranteed of sales of similar properties in order to de- minimum amount. Also, a type of insurance velop an estimate of the value of the prop- policy in which the policy holder makes erty. The analysis is called an “appraisal.” payments for a fixed period or until a stated age, and then receives annuity payments Appreciation: An increase in the market from the insurance company. -

INTERNAL REVENUE CODE SECTION 170(H): NATIONAL PERPETUITY STANDARDS for FEDERALLY SUBSIDIZED CONSERVATION EASEMENTS PART 1: the STANDARDS

INTERNAL REVENUE CODE SECTION 170(h): NATIONAL PERPETUITY STANDARDS FOR FEDERALLY SUBSIDIZED CONSERVATION EASEMENTS PART 1: THE STANDARDS Nancy A. McLaughlin Editors Synopsis: This Article is the first of two companion articles that (i) analyze the requirements in Internal Revenue Code section 170(h) that a deductible conservation easement be granted in perpetuity and its conservation purpose be protected in perpetuity and (ii) compare those requirements to state law provisions addressing the transfer, modification, or termination of conservation easements. This Article discusses the historical development of the federal charitable income tax deduction for conservation easement donations, the legislative history of section 170(h), and the Treasury Regulations interpreting that section. It explains that section 170(h) and the Treasury Regulations contain a complex web of requirements intended to ensure that a federal subsidy is provided only with respect to conservation easements that permanently protect unique or otherwise significant properties. Such requirements are also intended to ensure that, in the unlikely event changed conditions make continued use of the subject property for conservation or historic preservation purposes impossible or impractical and the easement is extinguished in a state court proceeding, the holder will receive proceeds and use those proceeds to replace the lost conservation or historic values on behalf of the public. The companion article, which will be published in the Winter 2010 edition of this journal, surveys the over one hundred statutes extant in the fifty states and the District of Columbia that authorize the creation or acquisition of conservation easements. That article explains that such statutes contain widely divergent transfer, modification, and termination provisions that were not, for the most part, crafted with an eye toward complying with federal tax law perpetuity requirements. -

Upper Hiwassee/Coker Creek Assessment

Cherokee National Forest USDA Forest Service Southern Region Roads Analysis Report Upper Hiwassee/Coker Creek Assessment September 2005 BACKGROUND On January 12, 2001, the National Forest System Road Management rule was published in the Federal Register. The adoption of the final rule revised the regulations concerning the management, use, and maintenance of the National Forest Transportation System. The purpose of this road analysis is to provide line officers with critical information to develop road systems that are safe and responsive to public needs and desires, are affordable and efficiently managed, have minimal negative ecological effects on the land, and are in balance with available funding for needed management actions. SCOPE The Upper Hiwassee/Coker Creek Assessment area is approximately 44,747 acres in size with approximately 21,468 of those acres National Forest System land (48% ownership). The majority of the assessment area (17,754 ac) is in Management Prescription (MP) 9.H of the Cherokee National Forest Revised Land and Resource Management Plan. Other MPs represented include: 4.F (443 ac), 7.B (2,126 ac), and 8.B (1,145 ac). Figure 1 displays the location of the analysis area within the Ocoee/Hiwassee Ranger District of the Cherokee National Forest. OBJECTIVES The main objectives of this road analysis are to: • Identify the need for change by comparing the current road system to the desired condition. • Inform the line officer of important ecological, social, and economic issues related to roads within the analysis area. EXISTING SYSTEM ROAD CONDITIONS Most of the study area is on National Forest System land, and of the roads assessed in and near the boundary of this study area, most are National Forest System Roads (NFSRs) under the jurisdiction and maintenance of the Forest Service. -

Property Ownership for Women Enriches, Empowers and Protects

ICRW Millennium Development Goals Series PROPERTY OWNERSHIP FOR WOMEN ENRICHES, EMPOWERS AND PROTECTS Toward Achieving the Third Millennium Development Goal to Promote Gender Equality and Empower Women It is widely recognized that if women are to improve their lives and escape poverty, they need the appropriate skills and tools to do so. Yet women in many countries are far less likely than men to own property and otherwise control assets—key tools to gaining eco- nomic security and earning higher incomes. Women’s lack of property ownership is important because it contributes to women’s low social status and their vulnerability to poverty. It also increasingly is linked to development-related problems, including HIV and AIDS, hunger, urbanization, migration, and domestic violence. Women who do not own property are far less likely to take economic risks and realize their full economic potential. The international community and policymakers increasingly are aware that guaranteeing women’s property and inheritance rights must be part of any development agenda. But no single global blueprint can address the complex landscape of property and inheritance practices—practices that are country- and culture-specific. For international development efforts to succeed—be they focused on reducing poverty broadly or empowering women purposely—women need effective land and housing rights as well as equal access to credit, technical information and other inputs. ENRICH, EMPOWER, PROTECT Women who own property or otherwise con- and tools—assets taken trol assets are better positioned to improve away when these women their lives and cope should they experience and their children need them most. -

Jurisdiction of a Tribunal - Extinguishment

Jurisdiction of a tribunal - extinguishment De Lacey v Juunyjuwarra People [2004] QCA 297 Davies JA, Mackenzie and Mullins JJ, 13 August 2004 Issue The main issue before the court was whether the Land and Resources Tribunal (LRT) established under the Mineral Resources Act 1989 (Qld) (the Act) had jurisdiction to determine whether the Starcke Pastoral Holdings Acquisition Act 1994 (Qld) extinguished native title in relation to an area the subject of a claimant application. Background In December 2003, Ralph De Lacey, an applicant for a ‘high impact’ exploration permit, applied to the LRT for a determination as to whether or not it had jurisdiction to decide that native title has been extinguished by the Act. On 27 February 2004, the LRT decided that it did have jurisdiction to determine that question and that it would be determined as a preliminary issue. An appeal against that decision was filed in the Supreme Court of Queensland by the State of Queensland. Decision Davies JA (with MacKenzie and Mullins JJ agreeing) held that: • there was no provision in the Act that contemplated an application to the LRT as was made in December 2003 or any decision by the LRT of the question stated in that application; • the LRT plainly saw that its jurisdiction to make the decision which it did make, was found in, or implied by, s. 669 of the Act, which governed the making of a ‘native title issues decision’ by the LRT. Where, in a proceeding otherwise properly instituted in a tribunal, there remains a condition upon the fulfilment or existence of which the jurisdiction of the tribunal exists (here, non-extinguishment of native title), the fulfilment or existence of that condition remains an outstanding question until it has been decided by a court competent to decide it: Parisienne Basket Shoes Pty Ltd v Whyte (1938) 59 CLR 359 at 391. -

Property Title Trouble in Non-Judicial Foreclosure States: the Ibanez Time Bomb?

William & Mary Business Law Review Volume 4 (2013) Issue 1 Article 5 February 2013 Property Title Trouble in Non-Judicial Foreclosure States: The Ibanez Time Bomb? Elizabeth Renuart Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmblr Part of the Secured Transactions Commons Repository Citation Elizabeth Renuart, Property Title Trouble in Non-Judicial Foreclosure States: The Ibanez Time Bomb?, 4 Wm. & Mary Bus. L. Rev. 111 (2013), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmblr/vol4/ iss1/5 Copyright c 2013 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmblr PROPERTY TITLE TROUBLE IN NON-JUDICIAL FORECLOSURE STATES: THE IBANEZ TIME BOMB? ELIZABETH RENUART ABSTRACT The economic crisis gripping the United States began when large numbers of homeowners defaulted on poorly underwritten subprime mort- gage loans. Demand from Wall Street seduced mortgage lenders, brokers, and other players to churn out mortgage loans in extraordinary numbers. Securitization, the process of utilizing mortgage loans to back investment instruments, fanned the fire. The resulting volume also caused the parties to these deals to often handle and transfer the legally important documents that secure the resulting investments—the loan notes and mortgages—in a careless and sometimes fraudulent manner. The consequences of this behavior are now becoming evident. All over the country, courts are scrutinizing whether the parties initiating foreclo- sures against homeowners have the right to take this action when the authority to enforce the note and mortgage is absent. Without this right, foreclosure sales can be reversed. -

Water Law in Real Estate Transactions

Denver Bar Association Real Estate Section Luncheon November 6, 2014 Water Law in Real Estate Transactions by Paul Noto, Esq. [email protected] Prior Appropriation Doctrine • Prior Appropriation Doctrine – First in Time, First in Right • Water allocated exclusively based on priority dates • Earliest priorities divert all they need (subject to terms in decree) • Shortages of water are not shared • “Pure” prior appropriation in CO A historical sketch of Colorado water law • Early rejection of the Riparian Doctrine, which holds that landowners adjacent to a stream can make a reasonable use of the water flowing through your land. – This policy was ill-suited to Colorado and would have hindered growth, given that climate and geography necessitate transporting water far from a stream to make land productive. • In 1861 the Territorial Legislature provided that water could be taken from the streams to lands not adjacent to streams. • In 1872, the Colorado Territorial Supreme Court recognized rights of way (easements), citing custom and necessity, through the lands of others for ditches carrying irrigation water to its place of use. Yunker v. Nichols, 1 Colo. 551, 570 (1872) A historical sketch of Colorado water law • In 1876 the Colorado Constitution declared: – “The water of every natural stream, not heretofore appropriated, within the state of Colorado, is hereby declared to be the property of the public, and the same is dedicated to the use of the people of the state, subject to appropriation as hereinafter provided.” Const. of Colo., Art. XVI, Sec. 5. – “The right to divert the unappropriated waters of any natural stream to beneficial uses shall never be denied. -

REAL ESTATE LAW LESSON 1 OWNERSHIP RIGHTS (IN PROPERTY) Real Estate Law Outline LESSON 1 Pg

REAL ESTATE LAW LESSON 1 OWNERSHIP RIGHTS (IN PROPERTY) Real Estate Law Outline LESSON 1 Pg Ownership Rights (In Property) 3 Real vs Personal Property 5 . Personal Property 5 . Real Property 6 . Components of Real Property 6 . Subsurface Rights 6 . Air Rights 6 . Improvements 7 . Fixtures 7 The Four Tests of Intention 7 Manner of Attachment 7 Adaptation of the Object 8 Existence of an Agreement 8 Relationships of the Parties 8 Ownership of Plants and Trees 9 Severance 9 Water Rights 9 Appurtenances 10 Interest in Land 11 Estates in Land 11 Allodial System 11 Kinds of Estates 12 Freehold Estates 12 Fee Simple Absolute 12 Defeasible Fee 13 Fee Simple Determinable 13 Fee Simple Subject to Condition Subsequent 14 Fee Simple Subject to Condition Precedent 14 Fee Simple Subject to an Executory Limitation 15 Fee Tail 15 Life Estates 16 Legal Life Estates 17 Homestead Protection 17 Non-Freehold Estates 18 Estates for Years 19 Periodic Estate 19 Estates at Will 19 Estate at Sufferance 19 Common Law and Statutory Law 19 Copyright by Tony Portararo REV. 08-2014 1 REAL ESTATE LAW LESSON 1 OWNERSHIP RIGHTS (IN PROPERTY) Types of Ownership 20 Sole Ownership (An Estate in Severalty) 20 Partnerships 21 General Partnerships 21 Limited Partnerships 21 Joint Ventures 22 Syndications 22 Corporations 22 Concurrent Ownership 23 Tenants in Common 23 Joint Tenancy 24 Tenancy by the Entirety 25 Community Property 26 Trusts 26 Real Estate Investment Trusts 27 Intervivos and Testamentary Trusts 27 Land Trust 27 TEST ONE 29 TEST TWO (ANNOTATED) 39 Copyright by Tony Portararo REV. -

Extinguishment of Agency General Condition Revocation Withdrawal Of

Extinguishment of Agency General condition Revocation Withdrawal of agent Death of the Principal Death of the Agent CASES Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila FIRST DIVISION G.R. No. L-36585 July 16, 1984 MARIANO DIOLOSA and ALEGRIA VILLANUEVA-DIOLOSA, petitioners, vs. THE HON. COURT OF APPEALS, and QUIRINO BATERNA (As owner and proprietor of QUIN BATERNA REALTY), respondents. Enrique L. Soriano for petitioners. Domingo Laurea for private respondent. RELOVA, J.: Appeal by certiorari from a decision of the then Court of Appeals ordering herein petitioners to pay private respondent "the sum of P10,000.00 as damages and the sum of P2,000.00 as attorney's fees, and the costs." This case originated in the then Court of First Instance of Iloilo where private respondents instituted a case of recovery of unpaid commission against petitioners over some of the lots subject of an agency agreement that were not sold. Said complaint, docketed as Civil Case No. 7864 and entitled: "Quirino Baterna vs. Mariano Diolosa and Alegria Villanueva-Diolosa", was dismissed by the trial court after hearing. Thereafter, private respondent elevated the case to respondent court whose decision is the subject of the present petition. The parties — petitioners and respondents-agree on the findings of facts made by respondent court which are based largely on the pre-trial order of the trial court, as follows: PRE-TRIAL ORDER When this case was called for a pre-trial conference today, the plaintiff, assisted by Atty. Domingo Laurea, appeared and the defendants, assisted by Atty. Enrique Soriano, also appeared. A. -

Real Property Conveyance Fee Statement of Value and Receipt

Real Property Conveyance Fee Statement of Value and Receipt DTE 100 If exempt by Ohio Revised Code section 319.54(G)(3), use form DTE 100(ex) Rev 1/14 FOR COUNTY AUDITOR’S USE ONLY Type Tax list County Tax Dist Date Instrument year number number Property located in ____________________________________________________________ taxing district Number Name on tax duplicate ____________________________________________ Tax duplicate year __________ Permanent Parcel Number _______________________________________ Map book _____ Page ______ Description ___________________________________________________ Platted Unplatted No. of Parcels Auditor’s comments: Split New plat New improvements Partial value C.A.U.V. Building removed Other __________________________________ DTE Code No. GRANTEE OR REPRESENTATIVE MUST COMPLETE ALL QUESTIONS IN THIS SECTION TYPE OR PRINT ALL INFORMATION SEE INSTRUCTIONS ON REVERSE Neigh. Code 1. Grantor’s Name _________________________________________________ Phone: ___________________________ 2. Grantee’s Name _________________________________________________ Phone: ___________________________ Grantee’s Address__________________________________________________________________________________ No. of Acres 3. Address of Property ________________________________________________________________________________ 4. Tax billing address _________________________________________________________________________________ Land Value 5. Are there buildings on the land? Yes No If yes, Check type: 1, 2 or 3 family dwelling Condominium -

Introduction to Law and Legal Reasoning Law Is

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION TO LAW AND LEGAL REASONING LAW IS "MAN MADE" IT CHANGES OVER TIME TO ACCOMMODATE SOCIETY'S NEEDS LAW IS MADE BY LEGISLATURE LAW IS INTERPRETED BY COURTS TO DETERMINE 1)WHETHER IT IS "CONSTITUTIONAL" 2)WHO IS RIGHT OR WRONG THERE IS A PROCESS WHICH MUST BE FOLLOWED (CALLED "PROCEDURAL LAW") I. Thomas Jefferson: "The study of the law qualifies a man to be useful to himself, to his neighbors, and to the public." II. Ask Several Students to give their definition of "Law." A. Even after years and thousands of dollars, "LAW" still is not easy to define B. What does law Consist of ? Law consists of enforceable rule governing relationships among individuals and between individuals and their society. 1. Students Need to Understand. a. The law is a set of general ideas b. When these general ideas are applied, a judge cannot fit a case to suit a rule; he must fit (or find) a rule to suit the unique case at hand. c. The judge must also supply legitimate reasons for his decisions. C. So, How was the Law Created. The law considered in this text are "man made" law. This law can (and will) change over time in response to the changes and needs of society. D. Example. Grandma, who is 87 years old, walks into a pawn shop. She wants to sell her ring that has been in the family for 200 years. Grandma asks the dealer, "how much will you give me for this ring." The dealer, in good faith, tells Grandma he doesn't know what kind of metal is in the ring, but he will give her $150. -

Conveyancing and the Law of Real Property

September 2014 - ISSUE 19 Conveyancing and The Law of Real Property The questions may be asked what is Conveyancing and why is Property Rules and his first act must be to undertake an inves‐ it attached to the Law of Real Property. tigation into the title of the Vendor’s property. This search which must be conducted in the Register of Deeds and should When dealing with the Law of Real Property there are two involve a period of time of thirty years or longer in the case fundamental points which must be understood‐‐‐ where the date of the Vendor’s Deed is older than thirty years. (i) You acquire knowledge of the rights and liabilities attached to the interests of the owner in the land and The Cause List search is undertaken in the Supreme Court Registry and the purpose of which is to ascertain whether (ii) The foundation of the Rules of Conveyancing. there are any liens pending against the Vendor in the Su‐ preme Court Register. If there are pending liens, they must be It is not easy to distinguish accurately between Real Property settled by the Vendor before he is able to sell the property. and Conveyancing. It is said that Real Property deals with the rights and liabilities of land owners. Conveyancing on the The original documents of title must be produced by the Ven‐ other hand is the art of creating and transferring rights in land dor and delivered to the attorney for review. I the Vendor is and thus the Rules of Conveyancing and the Law of Real Prop‐ unable to produce the same and the attorney has found the erty cannot be distinguished as separate subjects though re‐ title to be good and marketable, then the Vendor must sign lated closely but should be distinguished as two parts of one and swear an Affidavit of Loss in respect of such lost or mis‐ subject of land law.