Working with Data from the Solar Dynamics Observatory Daniel Brown, Stephane Regnier, Mike Marsh, and Danielle Bewsher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Activity - Sunspot Tracking

JOURNEY TO THE SUN WITH THE NATIONAL SOLAR OBSERVATORY Activity - SunSpot trAcking Adapted by NSO from NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA). https://sohowww.nascom.nasa.gov/classroom/docs/Spotexerweb.pdf / Retrieved on 01/23/18. Objectives In this activity, students determine the rate of the Sun’s rotation by tracking and analyzing real solar data over a period of 7 days. Materials □ Student activity sheet □ Calculator □ Pen or pencil bacKgrOund In this activity, you’ll observe and track sunspots across the Sun, using real images from the National Solar Observatory’s: Global Oscillation Network Group (GONG). This can also be completed with data students gather using www.helioviewer.org. See lesson 4 for instructions. GONG uses specialized telescope cameras to observe diferent layers of the Sun in diferent wavelengths of light. Each layer has a diferent story to tell. For example, the chromosphere is a layer in the lower solar atmosphere. Scientists observe this layer in H-alpha light (656.28nm) to study features such as flaments and prominences, which are clearly visible in the chromosphere. For the best view of sunspots, GONG looks to the photosphere. The photosphere is the lowest layer of the Sun’s atmosphere. It’s the layer that we consider to be the “surface” of the Sun. It’s the visible portion of the Sun that most people are familiar with. In order to best observe sunspots, scientists use photospheric light with a wavelength of 676.8nm. The images that you will analyze in this activity are of the solar photosphere. The data gathered in this activity will allow you to determine the rate of the Sun’s rotation. -

Ground-Based Solar Physics in the Era of Space Astronomy a White Paper Submitted to the 2012 Heliophysics Decadal Survey

Ground-Based Solar Physics in the Era of Space Astronomy A White Paper Submitted to the 2012 Heliophysics Decadal Survey T. Ayres1, D. Longcope2 (on behalf of the 2009 AURA Solar Decadal Committee) Chromosphere-Corona at eclipse Hα filtergram Photospheric spots & bright points Same area in chromospheric Ca+ 1Center for Astrophysics and Space Astronomy, 389 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309; [email protected] (corresponding author) 2Montana State University SUMMARY. A report, previously commissioned by AURA to support advocacy efforts in advance of the Astro2010 Decadal Survey, reached a series of conclusions concerning the future of ground-based solar physics that are relevant to the counterpart Heliophysics Survey. The main findings: (1) The Advanced Technology Solar Telescope (ATST) will continue U.S. leadership in large aperture, high-resolution ground-based solar observations, and will be a unique and powerful complement to space-borne solar instruments; (2) Full-Sun measurements by existing synoptic facilities, and new initiatives such as the Coronal Solar Magnetism Observatory (COSMO) and the Frequency Agile Solar Radiotelescope (FASR), will balance the narrow field of view captured by ATST, and are essential for the study of transient phenomena; (3) Sustaining, and further developing, synoptic observations is vital as well to helioseismology, solar cycle studies, and Space Weather prediction; (4) Support of advanced instrumentation and seeing compensation techniques for the ATST, and other solar telescopes, is necessary to keep ground-based solar physics at the cutting edge; and (5) Effective planning for ground-based facilities requires consideration of the synergies achieved by coordination with space-based observatories. -

The New Heliophysics Division Template

NASA Heliophysics Division Update Heliophysics Advisory Committee October 1, 2019 Dr. Nicola J. Fox Director, Heliophysics Division Science Mission Directorate 1 The Dawn of a New Era for Heliophysics Heliophysics Division (HPD), in collaboration with its partners, is poised like never before to -- Explore uncharted territory from pockets of intense radiation near Earth, right to the Sun itself, and past the planets into interstellar space. Strategically combine research from a fleet of carefully-selected missions at key locations to better understand our entire space environment. Understand the interaction between Earth weather and space weather – protecting people and spacecraft. Coordinate with other agencies to fulfill its role for the Nation enabling advances in space weather knowledge and technologies Engage the public with research breakthroughs and citizen science Develop the next generation of heliophysicists 2 Decadal Survey 3 Alignment with Decadal Survey Recommendations NASA FY20 Presidential Budget Request R0.0 Complete the current program Extended operations of current operating missions as recommended by the 2017 Senior Review, planning for the next Senior Review Mar/Apr 2020; 3 recently launched and now in primary operations (GOLD, Parker, SET); and 2 missions currently in development (ICON, Solar Orbiter) R1.0 Implement DRIVE (Diversify, Realize, Implemented DRIVE initiative wedge in FY15; DRIVE initiative is now Integrate, Venture, Educate) part of the Heliophysics R&A baseline R2.0 Accelerate and expand Heliophysics Decadal recommendation of every 2-3 years; Explorer mission AO Explorer program released in 2016 and again in 2019. Notional mission cadence will continue to follow Decadal recommendation going forward. Increased frequency of Missions of Opportunity (MO), including rideshares on IMAP and Tech Demo MO. -

A Recommendation for a Complete Open Source Policy

A recommendation for a complete open source policy. Authors Steven D. Christe, Research Astrophysicist, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, SunPy Founder and Board member Jack Ireland, Senior Scientist, ADNET Systems, Inc. / NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, SunPy Board Member Daniel Ryan, NASA Postdoctoral Fellow, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, SunPy Contributor Supporters SunPy Board ● Monica G. Bobra, Research Scientist, W. W. Hansen Experimental Physics Laboratory, Stanford University ● Russell Hewett, Research Scientist, Unaffiliated ● Stuart Mumford, Research Fellow, The University of Sheffield, SunPy Lead Developer ● David Pérez-Suárez, Senior Research Software Developer, University College London ● Kevin Reardon, Research Scientist, National Solar Observatory ● Sabrina Savage, Research Astrophysicist, NASA Marshall Space Flight Center ● Albert Shih, Research Astrophysicist, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Joel Allred, Research Astrophysicist, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Tiago M. D. Pereira, Researcher, Institute of Theoretical Astrophysics, University of Oslo Hakan Önel, Postdoctoral researcher, Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam, Germany Michael S. F. Kirk, Research Scientist, Catholic University of America / NASA GSFC The data that drives scientific advances continues to grow ever more complex and varied. Improvements in sensor technology, combined with the availability of inexpensive storage, have led to rapid increases in the amount of data available to scientists in almost every discipline. Solar physics is no exception to this trend. For example, NASAʼs Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) spacecraft, launched in February 2010, produces over 1TB of data per day. However, this data volume will soon be eclipsed by new instruments and telescopes such as the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope (DKIST) or the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST), which are slated to begin taking data in 2020 and 2022, respectively. -

Parker Solar Probe SWG Telecon February 5, 2020 Project Science Report Nour Raouafi Project Status Helene Winters Payload Status SB,JK,DM,RH Solar Orbiter H

Parker Solar Probe SWG Telecon February 5, 2020 Project Science Report Nour Raouafi Project Status Helene Winters Payload Status SB,JK,DM,RH Solar Orbiter H. Gilbert/C. St. Cyr SOC Activities Martha Kusterer Payload SE Telecon S. Hamilton/A. Reiter Theory Group M. Velli/A. Higginson Upcoming Meetings Nour Raouafi Science Presentations: DaviD Malaspina (LASP) & Karl Battams (NRL) Agenda • DCP 5 Information • DCP Type: Data Volume • Venus Flyby • Non-routine Activities & Science Priorities o WISPR o ISOIS o FIELDS o SWEAP • Modeling – Robert Allen • Coordinated observations. Parker Solar Probe Project Science SWG Telecon February 5, 2020 ApJS Special Issue (ApJ/SI) 50+ papers submitted as of Oct. 20, 2019 Early Results from Parker Solar Probe: Ushering a New Frontier in Space Exploration • Publication Date: February 3, 2020 • 48 papers accessible online • Few more papers still under review Corresponding authors: please speed up the reviewing process – Send me your submission info and the manuscript. • Print copies: Science Teams are you interested in ordering print copies of the special issue? 2/7/20 4 Nature Papers ADS not listing all the authors • ADS lists only three authors: the first two and the last one • The issue was addressed for the FIELDS and WISPR papers • But not for the SWEAP and ISOIS papers • ADS stated that that’s the information Nature sent to them • Corrections can submitted through http://adsabs.harvard.edu/adsfeedback/submit_abstract.php. 2/7/20 5 Future Publications • Let’s us know about your results in case we need to prepare for press releases • Animations take time to design and get ready • Please do not for the mission acknowledgements Parker Solar Probe was designed, built, and is now operated by the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory as part of NASA’s Living with a Star (LWS) program (contract NNN06AA01C). -

Sdo Sdt Report.Pdf

Solar Dynamics Observatory “…to understand the nature and source of the solar variations that affect life and society.” Report of the Science Definition Team Solar Dynamics Observatory Science Definition Team David Hathaway John W. Harvey K. D. Leka Chairman National Solar Observatory Colorado Research Division Code SD50 P.O. Box 26732 Northwest Research Assoc. NASA/MSFC Tucson, AZ 85726 3380 Mitchell Lane Huntsville, AL 35812 Boulder, CO 80301 Spiro Antiochos Donald M. Hassler David Rust Code 7675 Southwest Research Institute Applied Physics Laboratory Naval Research Laboratory 1050 Walnut St., Suite 426 Johns Hopkins University Washington, DC 20375 Boulder, Colorado 80302 Laurel, MD 20723 Thomas Bogdan J. Todd Hoeksema Philip Scherrer High Altitude Observatory Code S HEPL Annex B211 P. O. Box 3000 NASA/Headquarters Stanford University Boulder, CO 80307 Washington, DC 20546 Stanford, CA 94305 Joseph Davila Jeffrey Kuhn Rainer Schwenn Code 682 Institute for Astronomy Max-Planck-Institut für Aeronomie NASA/GSFC University of Hawaii Max Planck Str. 2 Greenbelt, MD 20771 2680 Woodlawn Drive Katlenburg-Lindau Honolulu, HI 96822 D37191 GERMANY Kenneth Dere Barry LaBonte Leonard Strachan Code 4163 Institute for Astronomy Harvard-Smithsonian Naval Research Laboratory University of Hawaii Center for Astrophysics Washington, DC 20375 2680 Woodlawn Drive 60 Garden Street Honolulu, HI 96822 Cambridge, MA 02138 Bernhard Fleck Judith Lean Alan Title ESA Space Science Dept. Code 7673L Lockheed Martin Corp. c/o NASA/GSFC Naval Research Laboratory 3251 Hanover Street Code 682.3 Washington, DC 20375 Palo Alto, CA 94304 Greenbelt, MD 20771 Richard Harrison John Leibacher Roger Ulrich CCLRC National Solar Observatory Department of Astronomy Chilton, Didcot P.O. -

The High Energy Telescope for STEREO

Space Sci Rev (2008) 136: 391–435 DOI 10.1007/s11214-007-9300-5 The High Energy Telescope for STEREO T.T. von Rosenvinge · D.V. Reames · R. Baker · J. Hawk · J.T. Nolan · L. Ryan · S. Shuman · K.A. Wortman · R.A. Mewaldt · A.C. Cummings · W.R. Cook · A.W. Labrador · R.A. Leske · M.E. Wiedenbeck Received: 1 May 2007 / Accepted: 18 December 2007 / Published online: 14 February 2008 © Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2008 Abstract The IMPACT investigation for the STEREO Mission includes a complement of Solar Energetic Particle instruments on each of the two STEREO spacecraft. Of these in- struments, the High Energy Telescopes (HETs) provide the highest energy measurements. This paper describes the HETs in detail, including the scientific objectives, the sensors, the overall mechanical and electrical design, and the on-board software. The HETs are designed to measure the abundances and energy spectra of electrons, protons, He, and heavier nuclei up to Fe in interplanetary space. For protons and He that stop in the HET, the kinetic energy range corresponds to ∼13 to 40 MeV/n. Protons that do not stop in the telescope (referred to as penetrating protons) are measured up to ∼100 MeV/n, as are penetrating He. For stop- ping He, the individual isotopes 3He and 4He can be distinguished. Stopping electrons are measured in the energy range ∼0.7–6 MeV. Keywords Space instrumentation · STEREO mission · Energetic particles · Coronal mass ejections · Particle acceleration PACS 96.50.Pw · 96.50.Vg · 96.60.ph Abbreviations 2-D Two dimensional ACE Advanced Composition Explorer ACRs Anomalous Cosmic Rays ADC Analog to Digital Converter T.T. -

A Mission to Touch the Sun

A Mission to Touch the Sun Presented by: David Malaspina Based on a huge amount of work by the NASA, APL, FIELDS, SWEAP, WISPR, ISOIS teams Who am I? Recent Space Plasma Group Missions: Van Allen Probes Assistant Professor in: Magnetospheric MultiScale (MMS) Professional Researcher in the Space Plasma Group (SPG) at: Parker Solar Probe Space Plasma Physicist Studying: The Solar Wind Planetary Magnetospheres Planetary Ionospheres Plasma Waves MAVEN Electric Field Sensors Spacecraft Charging A Tale in Four Acts [1] History - How do we know that a solar wind exists? - Why do we care? - What have we learned about the solar wind? [2] Solar Wind Science - Key unanswered questions - The need for a Solar Probe [3] Preparing a Mission - A battle for funding - Mission design - Instrument design [4] A Mission to Touch the Sun - Launch - First orbits - First results Per Act: The future ~10-15 min talk + - ~5-10 min questions Act 0: Terminology Plasma: A gas so hot, the atoms separate into electrons and ions - Ionization Common plasmas: - The Sun - Lightning plasma - Neon signs, fluorescent lights - TIG welders / Plasma cutters Plasmas have complicated motions: Fluid motion and electromagnetic motion Magnetic Field Simplest magnetic fields are dipoles north and south pole Iron filings “trace” magnetic field of a bar magnet by aligning with the field Sun Plasmas and magnetic fields Electrons and ions follow magnetic field lines in helical paths Earth Plasmas “trace” magnetic field lines Act 1: History Where to start? 1859 : The Colorado Gold Rush In 1858: 620 g of gold found in Little Dry Creek (now Englewood, CO) By 1860: ~100,000 gold-seekers had moved to Colorado 1858: City of Denver founded 1859: Boulder City Town Company organized https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Denver https://bouldercolorado.gov/visitors/history ‘‘On the night of [September 1] we were high up on the Rocky Mountains sleeping in the open air. -

Proposed Changes to Sacramento Peak Observatory Operations: Historic Properties Assessment of Effects

TECHNICAL REPORT Proposed Changes to Sacramento Peak Observatory Operations: Historic Properties Assessment of Effects Prepared for National Science Foundation October 2017 CH2M HILL, Inc. 6600 Peachtree Dunwoody Rd 400 Embassy Row, Suite 600 Atlanta, Georgia 30328 Contents Section Page Acronyms and Abbreviations ............................................................................................................... v 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Definition of Proposed Undertaking ................................................................................ 1-1 1.2 Proposed Alternatives Background ................................................................................. 1-1 1.3 Proposed Alternatives Description .................................................................................. 1-1 1.4 Area of Potential Effects .................................................................................................. 1-3 1.5 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 1-3 1.5.1 Determinations of Eligibility ............................................................................... 1-3 1.5.2 Finding of Effect .................................................................................................. 1-9 2 Identified Historic Properties ............................................................................................... -

Spektr-RG All-Sky Survey Will Be a Major Step Forward for X-Ray Astronomy, Which Celebrated Its 50Th Anniversary a Few Years Ago

CONTEXT The Spektr-RG all-sky survey will be a major step forward for X-ray astronomy, which celebrated its 50th anniversary a few years ago. 1962. Professor Riccardo Giacconi and his team are the first to identify X-ray emission originating from outside the Solar system (a neutron star dubbed Sco X-1). In 2002, he is awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for this feat and the following discoveries of distant X-ray sources. 1970–1973. The first X-ray all-sky survey in the 2–20 keV energy band is carried out by the Uhuru space observatory (NASA). It discovers more than 300 X-ray sources in our Milky Way and beyond. 1977–1979. An even more sensitive survey is carried out by the HEAO-1 (NASA) space observatory at energies from 0.25 to 180 keV. 1989-1998. Over the initial four years of directed observations, the Granat astrophysical observatory (USSR) observes many galactic and extra-galactic X-ray sources with emphasis on the deep imaging of the Center of our Galaxy in the hard (40-150 keV) and soft (4-20 keV) X-ray ranges. Unique maps of the Galactic Center in X- and gamma- rays are created; black holes, neutron stars and the first microquasar are discovered. Then Granat carries out a sensitive all-sky survey in the 40 to 200 keV energy band. 1990–1999. In its first six months of operation the ROSAT space observatory (DLR, NASA) performs a deep all-sky survey in the soft X-ray band (0.1–2.4 keV). -

Cryogenic Selective Surfaces

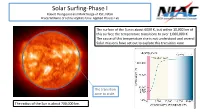

Solar Surfing-Phase I Robert Youngquist and Mark Nurge of KSC, NASA Bruce Williams of Johns Hopkins Univ. Applied Physics Lab The surface of the Sun is about 6000 K, but within 10,000 km of this surface the temperature transitions to over 1,000,000 K. The cause of this temperature rise is not understood and several Solar missions have set out to explore this transition zone. The transition zone to scale. The radius of the Sun is about 700,000 km. The Earth is about 214 Solar Radii from the Sun. Solar Surfing Mercury is about 100 Solar radii from the Sun. Helios B (1976) approached the Sun to within 62 Solar radii. The Parker Solar Probe will reach 8.5 Solar Radii from the surface Other Heliophysics Missions of the Sun, touching the edge of the corona! Solar Orbiter (2018) Solar Observatory (SOHO) (1995) Transition Region and Coronal PHOIBOS is an ESA Explorer (TRACE) (1998) proposed mission to We would like to get closer to the Solar Dynamics Observatory come with 3.5 Solar transition region and possibly even (SDO)(2010) Radii of the Sun. touch it. Solar Surfing The Parker Solar Probe Shield Solar Irradiance Spacecraft And Struts IR emission The Parker Solar Probe uses a Carbon Composite solar shield with a thin ceramic white scattering layer. The result is that about 60% of the Sun’s irradiance is absorbed. The carbon composite heats to as high as 1700 K; radiating the Sun’s absorbed power as infrared radiation. Behind the carbon composite is a thick layer of carbon foam insulation and customized struts, minimizing the transmission of heat to the spacecraft. -

Orbital Debris Environment Models, Such As NASA's LEGEND Model, Show That Accidental Collisions Between Satellites Will Begin

A Comparison of Catastrophic On-Orbit Collisions Gene Stansbery1 Mark Matney1 J.C. Liou1 Dave Whitlock2 1NASA Johnson Space Center, Houston, TX, USA 2ESCG/Hamilton Sundstrand, Houston, TX, USA Orbital debris environment models, such as NASA’s LEGEND model, show that accidental collisions between satellites will begin to be the dominant cause for future debris population growth within the foreseeable future. The collisional breakup models employed are obviously a critical component of the environment models. The Chinese Anti-Satellite (ASAT) test which destroyed the Fengyun-1C weather satellite provided a rare, but not unique, chance to compare the breakup models against an actual on-orbit collision. Measurements from the U.S. Space Surveillance Network (SSN), for debris larger than 10-cm, and from Haystack, for debris larger than 1-cm, show that the number of fragments created from Fengyun significantly exceeds model predictions using the NASA Standard Collision Breakup Model. However, it may not be appropriate to alter the model to match this one, individual case. At least three other on-orbit collisions have occurred which have produced significant numbers of debris fragments. In September 1985, the U.S. conducted an ASAT test against the Solwind P-78 spacecraft at an altitude of approximately 525 km. A year later, in September 1986, the Delta 180 payload was struck by its Delta II rocket body in a planned collision at 220 km altitude. And, in February 2008, the USA-193 satellite was destroyed by a ship launched missile in order to eliminate risk to humans on the ground from an on-board tank of frozen hydrazine.