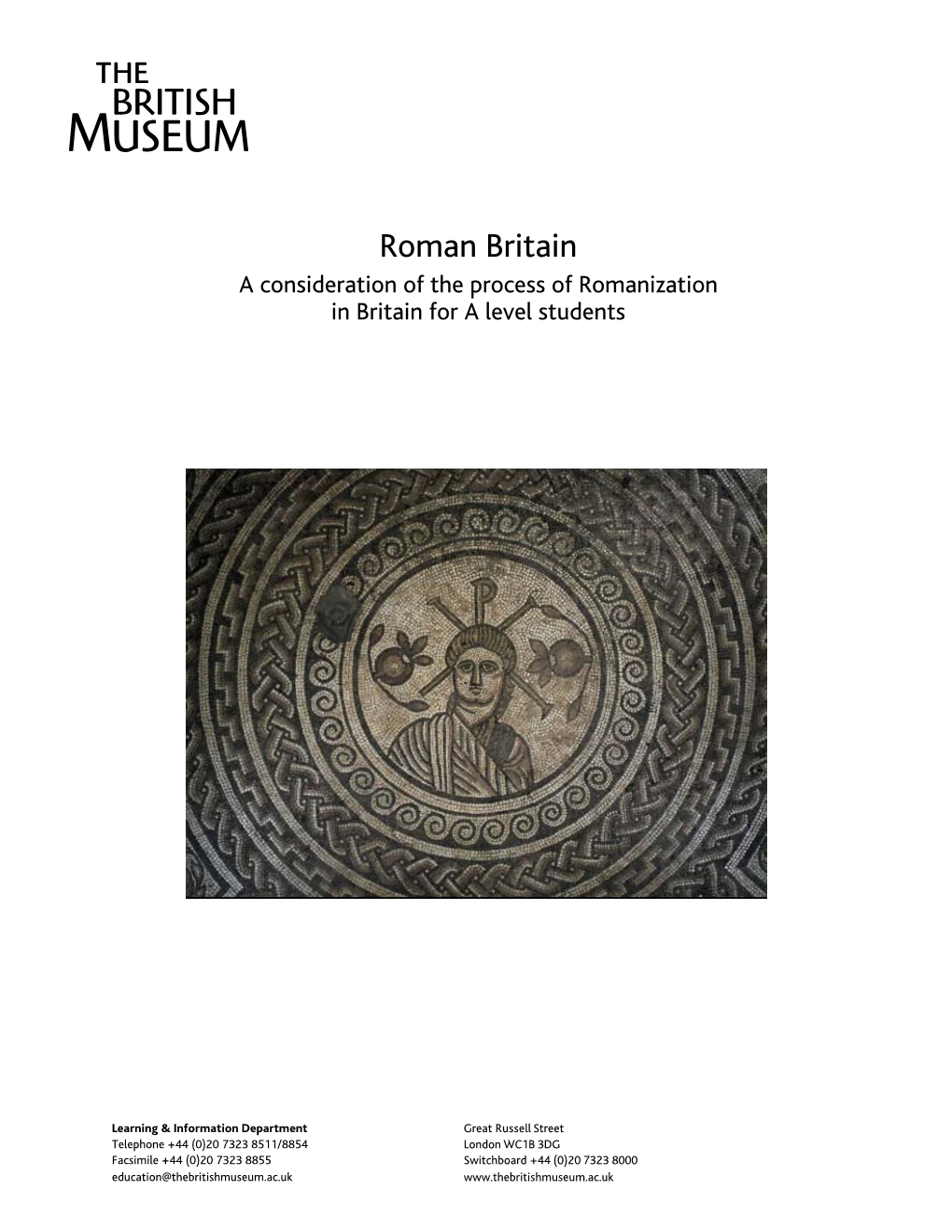

Roman Britain a Consideration of the Process of Romanization in Britain for a Level Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Caledonia 1698-1700: Scotland's Twice-Lost Colony

71 “New Caledonia 1698-1700: Scotland’s Twice-Lost Colony” Ignacio Gallup-Díaz, Bryn Mawr College “Lost Colonies” Conference, March 26-27, 2004 (Please do not cite, quote, or circulate without written permission from the author) This paper explores the manner in which the troubled relationship between Scotland and England played itself out in the arena of imperial expansion in the Americas. How did Scotland, a nation-state attempting to free itself from its problematic relationship with a mightier southern neighbor, act upon the colonial stage it had chosen in the Darién region of eastern Panamá? How did a nation-state that occupied the subject position in a colonial relationship itself perform as a colonizer? Informed by David Armitage’s persuasive description of the elements that differentiated the Scottish vision of empire from English expansionist thinking,1 the paper sets out to discover whether Scottish sailors, soldiers and settlers-- the individuals acting on the front lines of the nation’s expansionist effort-- interacted with the Darién’s Tule2 people in a manner that also distinguished them from their English competitors. 1. D. Armitage, “The Scottish Vision of Empire: Intellectual Origins of the Darién Venture,” in John Robertson, ed., A Union for Empire: Political Thought and the Union of 1707, (Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 97-121; see also his Ideological Origins of the British Empire, (Cambridge UP, 2000), pp. 158-162. 2. The San Blas Kuna Indians, the descendants of the early modern indigenous peoples of Panamá, use the word “Tule” to describe themselves, and this is the term that I shall use for the actors in this paper. -

Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 5-16-2016 12:00 AM Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain Robert Jackson Woodcock The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Professor Alexander Meyer The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Classics A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Robert Jackson Woodcock 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Indo- European Linguistics and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Woodcock, Robert Jackson, "Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3775. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3775 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Language is one of the most significant aspects of cultural identity. This thesis examines the evidence of languages in contact in Roman Britain in order to determine the role that language played in defining the identities of the inhabitants of this Roman province. All forms of documentary evidence from monumental stone epigraphy to ownership marks scratched onto pottery are analyzed for indications of bilingualism and language contact in Roman Britain. The language and subject matter of the Vindolanda writing tablets from a Roman army fort on the northern frontier are analyzed for indications of bilingual interactions between Roman soldiers and their native surroundings, as well as Celtic interference on the Latin that was written and spoken by the Roman army. -

A Guide to Ceramic Building Materials

A Guide To Ceramic Building Materials An Insight Report By J.M. McComish ©York Archaeological Trust for Excavation and Research 2015 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 5 2. METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................................. 5 3. ROMAN CERAMIC BUILDING MATERIAL (LATE 1ST TO 4TH CENTURY AD)..................................... 6 3.1 ANTEFIX ................................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 BESSALIS .................................................................................................................................. 8 3.3 CHIMNEY ................................................................................................................................. 9 3.4 FLUE ...................................................................................................................................... 10 3.5 IMBREX .................................................................................................................................. 11 3.6 LYDION .................................................................................................................................. 12 3.7 NON-STANDARD SHAPES ........................................................................................................... 13 3.8 OPUS SPICATUM ..................................................................................................................... -

The Romanization of Romania: a Look at the Influence of the Roman Military on Romanian History and Heritage Colleen Ann Lovely Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2016 The Romanization of Romania: A Look at the Influence of the Roman Military on Romanian History and Heritage Colleen Ann Lovely Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Lovely, Colleen Ann, "The Romanization of Romania: A Look at the Influence of the Roman Military on Romanian History and Heritage" (2016). Honors Theses. 178. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/178 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Romanization of Romania: A Look at the Influence of the Roman Military on Romanian History and Heritage By Colleen Ann Lovely ********* Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Departments of Classics and Anthropology UNION COLLEGE March 2016 Abstract LOVELY, COLLEEN ANN The Romanization of Romania: A Look at the Influence of the Roman Military on Romanian History and Heritage. Departments of Classics and Anthropology, March 2016. ADVISORS: Professor Stacie Raucci, Professor Robert Samet This thesis looks at the Roman military and how it was the driving force which spread Roman culture. The Roman military stabilized regions, providing protection and security for regions to develop culturally and economically. Roman soldiers brought with them their native cultures, languages, and religions, which spread through their interactions and connections with local peoples and the communities in which they were stationed. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Fishbourne: a Roman Palace and Its Garden, 1971, Barry W. Cunliffe, 0801812666, 9780801812668, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1971

Fishbourne: A Roman Palace and Its Garden, 1971, Barry W. Cunliffe, 0801812666, 9780801812668, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1971 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1O80BJ2 http://goo.gl/Rblvo http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fishbourne_A_Roman_Palace_and_Its_Garden DOWNLOAD http://goo.gl/R4Dxp http://bit.ly/W9p35D The Roman Villa in Britain , Albert Lionel Frederick Rivet, 1969, Pavements, Mosaic, 299 pages. Excavations at Fishbourne, 1961-1969, Issue 26, Volume 1 , Barry W. Cunliffe, 1971, History, 221 pages. Facing the Ocean The Atlantic and Its Peoples, 8000 BC-AD 1500, Barry W. Cunliffe, Jan 1, 2001, History, 600 pages. An illustrated history of the peoples of "the Atlantic rim" explores the inter- relatedness of European cultures that stretched from Iceland to Gibralter.. The Romans at Ribchester discovery and excavation, B. J. N. Edwards, University of Lancaster. Centre for North-West Regional Studies, Jan 1, 2000, History, 101 pages. Germania , Cornelius Tacitus, 1970, History, 175 pages. Offers a portrait of Julius Agricola - the governor of Roman Britain and Tacitus' father-in-law - and an account of Britain that has come down to us. This book provides. The Recent Discoveries of Roman Remains Found in Repairing the North Wall of the City of Chester (A Series of Papers Read Before the Chester Archaeological and Historic Society, Etc., and Reprinted by Permission of the Council.) Extensively Illustrated, John Parsons Earwaker, 1888, Romans, 175 pages. Roman Canterbury, as so far revealed by the work of the Canterbury Excavation Committee , Canterbury Excavation Committee, 1949, History, 16 pages. Roman Silchester the archaeology of a Romano-British town, George C. Boon, 1957, Silchester (England), 245 pages. -

The Roman Baths Complex Is a Site of Historical Interest in the English City of Bath, Somerset

Aquae Sulis The Roman Baths complex is a site of historical interest in the English city of Bath, Somerset. It is a well-preserved Roman site once used for public bathing. Caerwent Caerwent is a village founded by the Romans as the market town of Venta Silurum. The modern village is built around the Roman ruins, which are some of the best-preserved in Europe. Londinium Londinium was a settlement established on the current site of the City of London around 43 AD. Its bridge over the River Thames turned the city into a road nexus and major port, serving as a major commercial centre in Roman Britain until its abandonment during the 5th century. Dere Street Dere Street or Deere Street is what is left of a Roman road which ran north from Eboracum (York), and continued beyond into what is now Scotland. Parts of its route are still followed by modern roads that we can drive today. St. Albans St. Albans was the first major town on the old Roman road of Watling Street. It is a historic market town and became the Roman city of Verulamium. St. Albans takes its name from the first British saint, Albanus, who died standing up for his beliefs. Jupiter Romans believed Jupiter was the god of the sky and thunder. He was king of the gods in Ancient Roman religion and mythology. Jupiter was the most important god in Roman religion throughout the Empire until Christianity became the main religion. Juno Romans believed Juno was the protector of the Empire. She was an ancient Roman goddess who was queen of all the gods. -

Two Studies on Roman London. Part B: Population Decline and Ritual Landscapes in Antonine London

Two Studies on Roman London. Part B: population decline and ritual landscapes in Antonine London In this paper I turn my attention to the changes that took place in London in the mid to late second century. Until recently the prevailing orthodoxy amongst students of Roman London was that the settlement suffered a major population decline in this period. Recent excavations have shown that not all properties were blighted by abandonment or neglect, and this has encouraged some to suggest that the evidence for decline may have been exaggerated.1 Here I wish to restate the case for a significant decline in housing density in the period circa AD 160, but also draw attention to evidence for this being a period of increased investment in the architecture of religion and ceremony. New discoveries of temple complexes have considerably improved our ability to describe London’s evolving ritual landscape. This evidence allows for the speculative reconstruction of the main processional routes through the city. It also shows that the main investment in ceremonial architecture took place at the very time that London’s population was entering a period of rapid decline. We are therefore faced with two puzzling developments: why were parts of London emptied of houses in the middle second century, and why was this contraction accompanied by increased spending on religious architecture? This apparent contradiction merits detailed consideration. The causes of the changes of this period have been much debated, with most emphasis given to the economic and political factors that reduced London’s importance in late antiquity. These arguments remain valid, but here I wish to return to the suggestion that the Antonine plague, also known as the plague of Galen, may have been instrumental in setting London on its new trajectory.2 The possible demographic and economic consequences of this plague have been much debated in the pages of this journal, with a conservative view of its impact generally prevailing. -

Download the KAFS Booking Form for All of Our Forthcoming Courses Directly from Our Website, Or by Clicking Here

WELCOME TO THE JANUARY NEWSETTER EDITORIAL FROM KAFS MUST SEE STUDY DAYS We will be sending a Newsletter email each month to keep you up to date FIELD TRIPS with news and views on what is planned at the Kent Archaeological Field School and what is happening on the larger stage of archaeology both in BREAKING NEWS this country and abroad. Talking of which we are extremely lucky this year to READING AT THE MOMENT be able to dig with the University of Texas at Oplontis just next door to Pompeii. We have just three places left so hurry with that booking! SHORT STORY COURSES KAFS BOOKING FORM At home we are digging the last of three Bronze Age round barrows at Hollingbourne in Kent where last year in Barrow 2 we found a crouched burial and a complete bovine burial (below). Work will continue on two Roman villa estates, one at Abbey Farm in Faversham, the other at Teston located above the River Medway close to Maidstone. Work will continue on two Roman villa estates, one at Abbey Farm in Faversham, the other at Teston located above the River Medway close to Maidstone. So, look at our web site at www.kafs.co.uk in 2014 for details of courses and ‘behind the scenes’ trips with KAFS. We hear all the time in the press about threats to our woodland and heritage and Rescue has over many years brought our attention to the ‘creeping threat’ of development on our historic wellbeing. Dr Chris Cumberpatch has written this letter to the Times which we need to take notice of: Sir, After your report and letters (Jan 2) it is time to stand back and look at what we may be allowing to be done to this country in the name of development and its presumed role as the solution to our economic woes. -

RULES of PLAY COIN Series, Volume VIII by Marc Gouyon-Rety

The Fall of Roman Britain RULES OF PLAY COIN Series, Volume VIII by Marc Gouyon-Rety T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S 1.0 Introduction ............................2 6.0 Epoch Rounds .........................18 2.0 Sequence of Play ........................6 7.0 Victory ...............................20 3.0 Commands .............................7 8.0 Non-Players ...........................21 4.0 Feats .................................14 Key Terms Index ...........................35 5.0 Events ................................17 Setup and Scenarios.. 37 © 2017 GMT Games LLC • P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232 • www.GMTGames.com 2 Pendragon ~ Rules of Play • 58 Stronghold “castles” (10 red [Forts], 15 light blue [Towns], 15 medium blue [Hillforts], 6 green [Scotti Settlements], 12 black [Saxon Settlements]) (1.4) • Eight Faction round cylinders (2 red, 2 blue, 2 green, 2 black; 1.8, 2.2) • 12 pawns (1 red, 1 blue, 6 white, 4 gray; 1.9, 3.1.1) 1.0 Introduction • A sheet of markers • Four Faction player aid foldouts (3.0. 4.0, 7.0) Pendragon is a board game about the fall of the Roman Diocese • Two Epoch and Battles sheets (2.0, 3.6, 6.0) of Britain, from the first large-scale raids of Irish, Pict, and Saxon raiders to the establishment of successor kingdoms, both • A Non-Player Guidelines Summary and Battle Tactics sheet Celtic and Germanic. It adapts GMT Games’ “COIN Series” (8.1-.4, 8.4.2) game system about asymmetrical conflicts to depict the political, • A Non-Player Event Instructions foldout (8.2.1) military, religious, and economic affairs of 5th Century Britain. -

Annals of the Caledonians, Picts and Scots

Columbia (HnitJer^ftp intlifCttpufUmigdrk LIBRARY COL.COLL. LIBRARY. N.YORK. Annals of t{ie CaleDoiuans. : ; I^col.coll; ^UMl^v iV.YORK OF THE CALEDONIANS, PICTS, AND SCOTS AND OF STRATHCLYDE, CUMBERLAND, GALLOWAY, AND MURRAY. BY JOSEPH RITSON, ESQ. VOLUME THE FIRST. Antiquam exquirite matrem. EDINBURGH PRINTED FOR W. AND D. LAING ; AND PAYNE AND FOSS, PALL-MALL, LONDON. 1828. : r.DiKBURnii FIlINTEn I5Y BAI.LANTTNK ASn COMPAKV, Piiiri.'S WOKK, CANONGATK. CONTENTS. VOL. I. PAGE. Advertisement, 1 Annals of the Caledonians. Introduction, 7 Annals, -. 25 Annals of the Picts. Introduction, 71 Annals, 135 Appendix. No. I. Names and succession of the Pictish kings, .... 254 No. II. Annals of the Cruthens or Irish Picts, 258 /» ('^ v^: n ,^ '"1 v> Another posthumous work of the late Mr Rlt- son is now presented to the world, which the edi- tor trusts will not be found less valuable than the publications preceding it. Lord Hailes professes to commence his interest- ing Annals with the accession of Malcolm III., '* be- cause the History of Scotland, previous to that pe- riod, is involved in obscurity and fable :" the praise of indefatigable industry and research cannot there- fore be justly denied to the compiler of the present volumes, who has extended the supposed limit of authentic history for many centuries, and whose labours, in fact, end where those of his predecessor hegi7i. The editor deems it a conscientious duty to give the authors materials in their original shape, " un- mixed with baser matter ;" which will account for, and, it is hoped, excuse, the trifling repetition and omissions that sometimes occur. -

A Modern History of Britain's Roman Mosaic Pavements

Spectacle and Display: A Modern History of Britain’s Roman Mosaic Pavements Michael Dawson Archaeopress Roman Archaeology 79 Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-831-2 ISBN 978-1-78969-832-9 (e-Pdf) © Michael Dawson and Archaeopress 2021 Front cover image: Mosaic art or craft? Reading Museum, wall hung mosaic floor from House 1, Insula XIV, Silchester, juxtaposed with pottery by the Aldermaston potter Alan Gaiger-Smith. Back cover image: Mosaic as spectacle. Verulamium Museum, 2007. The triclinium pavement, wall mounted and studio lit for effect, Insula II, Building 1 in Verulamium 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents List of figures.................................................................................................................................................iii Preface ............................................................................................................................................................v 1 Mosaics Make a Site ..................................................................................................................................1 Introduction ..............................................................................................................................................1