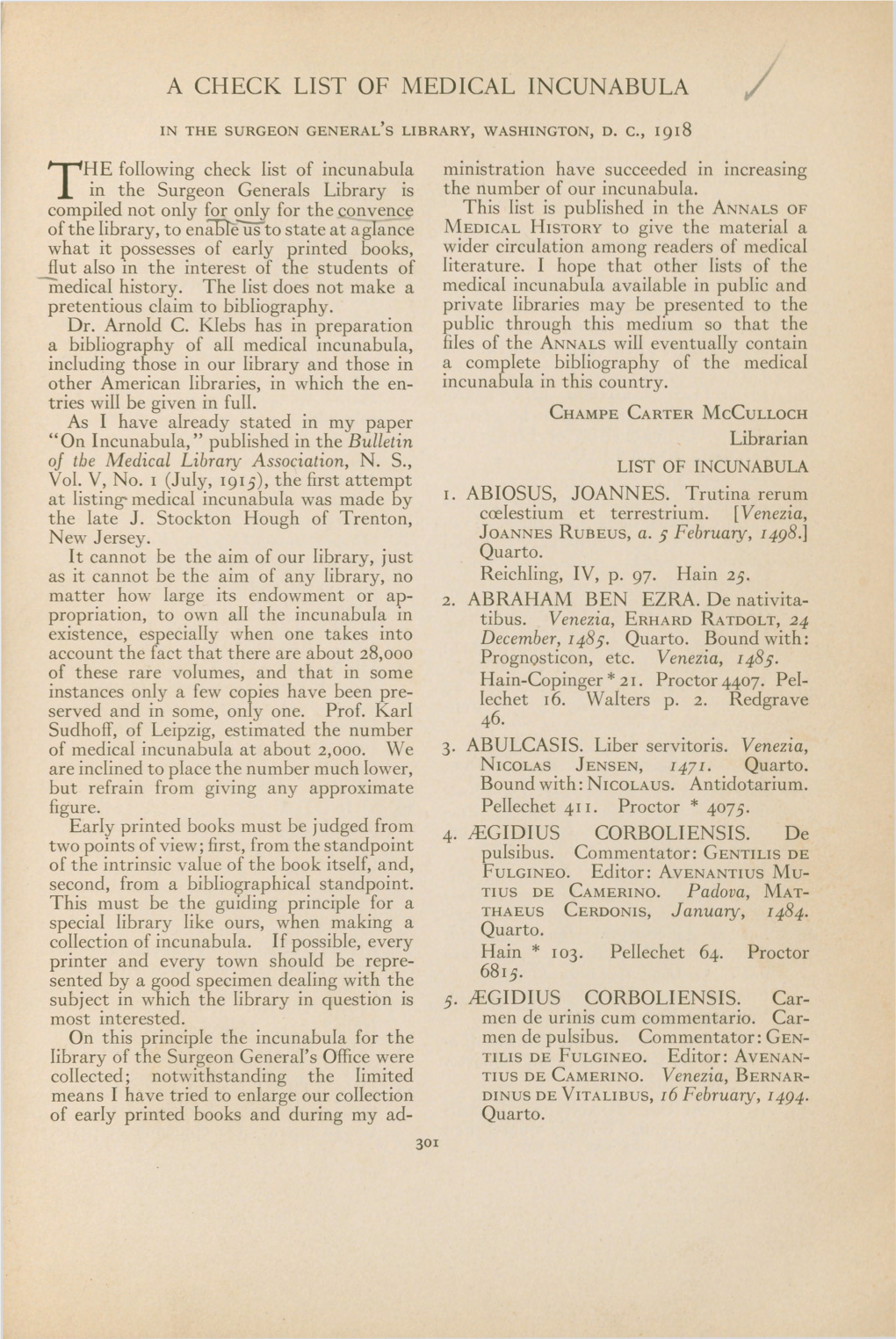

A Check List of Medical Incunabula in the Surgeon General's Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages

jussi hanska Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages Studia Fennica Historica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia fennica editorial board Anna-Leena Siikala Rauno Endén Teppo Korhonen Pentti Leino Auli Viikari Kristiina Näyhö Editorial Office SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.finlit.fi Jussi Hanska Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages Finnish Literature Society · Helsinki Studia Fennica Historica 2 The publication has undergone a peer review. The open access publication of this volume has received part funding via a Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation grant. © 2002 Jussi Hanska and SKS License CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. International A digital edition of a printed book first published in 2002 by the Finnish Literature Society. Cover Design: Timo Numminen EPUB Conversion: eLibris Media Oy ISBN 978-951-746-357-7 (Print) ISBN 978-952-222-818-5 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-222-819-2 (EPUB) ISSN 0085-6835 (Studia Fennica) ISSN 0355-8924 (Studia Fennica Historica) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21435/sfh.2 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. -

Agrarian Metaphors 397

396 Agrarian Metaphors 397 The Bible provided homilists with a rich store of "agricultural" metaphors and symbols) The loci classici are passages like Isaiah's "Song of the Vineyard" (Is. 5:1-7), Ezekiel's allegories of the Tree (Ez. 15,17,19:10-14,31) and christ's parables of the Sower (Matt. 13: 3-23, Mark 4:3-20, Luke 8:5-15) ,2 the Good Seed (Matt. 13:24-30, Mark 4:26-29) , the Barren Fig-tree (Luke 13:6-9) , the Labourers in the Vineyard (Matt. 21:33-44, Mark 12:1-11, Luke 20:9-18), and the Mustard Seed (Matt. 13:31-32, Mark 4:30-32, Luke 13:18-19). Commonplace in Scripture, however, are comparisons of God to a gardener or farmer,5 6 of man to a plant or tree, of his soul to a garden, 7and of his works to "fruits of the spirit". 8 Man is called the "husbandry" of God (1 Cor. 3:6-9), and the final doom which awaits him is depicted as a harvest in which the wheat of the blessed will be gathered into God's storehouse and the chaff of the damned cast into eternal fire. Medieval scriptural commentaries and spiritual handbooks helped to standardize the interpretation of such figures and to impress them on the memories of preachers (and their congregations). The allegorical exposition of the res rustica presented in Rabanus Maurus' De Universo (XIX, cap.l, "De cultura agrorum") is a distillation of typical readings: Spiritaliter ... in Scripturis sacris agricultura corda credentium intelliguntur, in quibus fructus virtutuxn germinant: unde Apostolus ad credentes ait [1 Cor. -

The English Dream Vision

The English Dream Vision ANATOMY OF A FORM J. Stephen Russell The English Dream Vision ANATOMY OF A FORM By J. Stephen Russell The first-person dream-frame nar rative served as the most popular English poetic form in the later Mid dle Ages. In The English Dream Vision, Stephen Russell contends that the poetic dreams of Chaucer, Lang- land, the Pearl poet, and others employ not simply a common exter nal form but one that contains an internal, intrinsic dynamic or strategy as well. He finds the roots of this dis quieting poetic form in the skep ticism and nominalism of Augustine, Macrobius, Guillaume de Lorris, Ockham, and Guillaume de Conches, demonstrating the interdependence of art, philosophy, and science in the Middle Ages. Russell examines the dream vision's literary contexts (dreams and visions in other narratives) and its ties to medieval science in a review of medi eval teachings and beliefs about dreaming that provides a valuable survey of background and source material. He shows that Chaucer and the other dream-poets, by using the form to call all experience into ques tion rather than simply as an authen ticating device suggesting divine revelation, were able to exploit con temporary uncertainties about dreams to create tense works of art. continued on back flap "English, 'Dream Vision Unglisfi (Dream Vision ANATOMY OF A FORM J. Stephen Russell Ohio State University Press • Columbus Copyright © 1988 by the Ohio State University Press. All rights reserved. Quotations from the works of Chaucer are taken from The Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, ed. -

Index of Names, Places and Texts

Index of Names, Places and Texts Agincourt 296n131 Auriol, Peter 15, 39, 48 Aiguani, Michael, of Bologna 18 Compendium litteralis sensus totius d’Ailly, Pierre 18, 41n44 Bibliae 14, 39n37, 48n71, 297 Aldgate, Augustinian priory of Holy Avignon 17 Trinity 300 Alfonsus, Peter, Disciplina clericalis 101 Baber, Henry Hervey 452, 455 Alfred, king 24, 49 Bacon, Roger 20, 126, 140 Alnwick, William 224, 385–6 Baconthorpe, John 16, 17, 19 d’Alsace, Laurette 59 Badby, John 86 Ambrose, St 357 Bagster, Samuel, The English Hexapla 452 Amerie, John 439–40 Baker, John 224n6 Ancrene Riwle 64, 90, 94 Baldwin, William, Mirror for Magistrates Andreae, Johannes 23 444 Anglo-Norman Bible 56, 57, 58n34, 65 Bale, John 153, 434, 437 Antwerp 430 Scriptorum illustrium maioris Brytanniae Apocalypse, Middle English 56n23 Catalogus 450–1 Apocalips of Jesu Crist 88, 89–94, 96, 97, Banwell, William 383 104, 440 Baranhon, Bernard Raymond 24 Aquila 175 Bardfield, John 384 Aquinas, Thomas 13, 14, 32, 75n31, 292, 356, Bardfield, Margery 384 358 Barking, Benedictine nunnery 239, 242–3 De potentia 32n13 Barnes, Robert 429–30 Summa theologiae 33n16 Barret, John 384 Aristotle 15, 20, 31, 34, 74n24, 75n31 Bartholomeus Anglicus, De proprietatibus Ethics 29 rerum 153, 154, 155, 156 Arundel, Thomas 6, 25, 26, 86, 87, 104, 135, St Bartholomew’s, Smithfield 260n29 157, 161, 181n72, 371, 373, 375, 389, 402–5, Basel 83 425, 427 Baxter, Margery 224n6 Assisi, Francis of 39 Bayly, Thomas 383 Aston, John 373 Baysio, Guido de 171 Augustine 16, 25, 29, 75n31, 126, 148, 158, 171, Beachamwell, Norfolk 441 182, 196, 349, 357, 358, 359, 362, 363, 364, Bede 24, 25, 49, 60, 158 391, 395, 401 Bedfordshire 203, 205, 215, 217 De consensu evangelistarum 95 Beleth, John, Summa de ecclesiasticis De doctrina christiana 28, 29n5, 170, officiis 241 181n70, 357 Benedictine 11, 69, 74, 79, 67n5, 79, 153, De magistro 38n33 268n10, 444 Enarrationes in Psalmos 351n13, 357, 360 Berengaudus 63 Epistle 93 170 Berkeley, Thomas 153, 230, 293 In Iohannis Evangelium 357 Bermondsey, Cluniac monastery of Soliloquies 170 St Saviour 297n135 St. -

Approaches to the Extramission Postulate in 13Th Century Theories of Vision Lukáš Lička

The Visual Process: Immediate or Successive? Approaches to the Extramission Postulate in 13th Century Theories of Vision Lukáš Lička [Penultimate draft. For the published version, see L. Lička, “The Visual Process: Immediate or Successive? Approaches to the Extramission Postulate in 13th Century Theories of Vision”, in Medieval Perceptual Puzzles: Theories of Sense-Perception in the 13th and 14th Centuries, edited by E. Băltuță, Leiden: Brill, 2020, pp. 73–110.] Introduction Is vision merely a state of the beholder’s sensory organ which can be explained as an immediate effect caused by external sensible objects? Or is it rather a successive process in which the observer actively scanning the surrounding environment plays a major part? These two general attitudes towards visual perception were both developed already by ancient thinkers. The former is embraced by natural philosophers (e.g., atomists and Aristotelians) and is often labelled “intromissionist”, based on their assumption that vision is an outcome of the causal influence exerted by an external object upon a sensory organ receiving an entity from the object. The latter attitude to vision as a successive process is rather linked to the “extramissionist” theories of the proponents of geometrical optics (such as Euclid or Ptolemy) who suggest that an entity – a visual ray – is sent forth from the eyes to the object.1 The present paper focuses on the contributions to this ancient controversy proposed by some 13th-century Latin thinkers. In contemporary historiography of medieval Latin philosophy, the general narrative is that whereas thinkers in the 12th century held various (mostly Platonic) versions of the extramission theory, the situation changes during the first half of the 13th century when texts by Avicenna, Aristotle (with the commentaries by Averroes), and especially Alhacen, who all favour the intromissionist paradigm, were gradually assimilated.2 It is assumed that, as a result, 1 For an account of the ancient theories of vision based on this line of conflict see especially D. -

Medical Literacy in Medieval England and the Erasure of Anglo-Saxon Medical Knowledge

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: LINGUISTIC ORPHAN: MEDICAL LITERACY IN MEDIEVAL ENGLAND AND THE ERASURE OF ANGLO-SAXON MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE Margot Rochelle Willis, Master of Arts in History, 2018 Thesis Directed By: Dr. Janna Bianchini, Department of History This thesis seeks to answer the question of why medieval physicians “forgot” efficacious medical treatments developed by the Anglo-Saxons and how Anglo- Saxon medical texts fell into obscurity. This thesis is largely based on the 2015 study of Freya Harrison et al., which replicated a tenth-century Anglo-Saxon eyesalve and found that it produced antistaphylococcal activity similar to that of modern antibiotics. Following an examination of the historiography, primary texts, and historical context, this thesis concludes that Anglo-Saxon medical texts, regardless of what useful remedies they contained, were forgotten primarily due to reasons of language: the obsolescence of Old English following the Norman Conquest, and the dominance of Latin in the University-based medical schools in medieval Europe. LINGUISTIC ORPHAN: MEDICAL LITERACY IN MEDIEVAL ENGLAND AND THE ERASURE OF ANGLO-SAXON MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE by Margot Rochelle Willis Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History 2018 Advisory Committee: Associate Professor Janna Bianchini, Chair Associate Professor Antoine Borrut Professor Mary Francis Giandrea © Copyright by Margot Rochelle Willis 2018 Dedication To my parents, without whose encouragement I would have never had the courage to make it where I am today, and who have been lifelong sources of support, guidance, laughter, and love. -

Of Historical Authors

Index of Historical Authors Abbadie, Jacques 168, 169n30 Cassian, John 69n1, 75 Abelard, Peter 33, 38, 40, 41 Cassiodorus 53 Adams, Thomas 177 Catullus 226n5, 230n18 Adolph, Johann Baptist 241n55 Caussin, Nicolas 181, 180–96, 229, 230, 240 Alain de Lille 15n5, 18, 19, 20, 27, 73n18 Chaillou, Jacques 267 Alberti, Leon Battista 167 Charas, Moyse 267 Albertus Magnus 17, 20, 21, 89, 90, 93, 102 Chirac, Pierre 277 Ambrose of Milan 76, 94, 190 Chomel, Noël 267, 268n21, 275n57 Ammanati, Bartolommeo 176 Chrysippus 110, 114 Aquinas, Thomas 13, 14, 15n3, 16, 17, 33, 38, Cicero, Marcus Tullius 88, 90, 94, 109, 110, 60, 67, 76, 89, 90, 98, 169, 181, 182, 183n9, 111n25, 112–116, 119n60, 120, 228, 229 184, 191, 192, 249 Conty, Evrart de 91 Aristotle 14, 16, 48–50, 52, 53, 57, 59, 62, 63, Coppe, Abiezer 177 67, 89, 91, 93, 94, 112n27, 163, 168, 182, Crantor 113 184–187, 191, 192, 228 Crighton, Alexander 203 Arriaga, Roderigo de 186n19 Auger, Edmond 128, 147, 156 Dante Alighieri 16 Augustine of Hippo 21, 38, 44, 76, 88, 89, 94, Deidier, Antoine 272, 273, 274n50 102, 112n27, 119n60, 163, 183, 190, 192, 248 Descartes, René 38, 203, 204 Avicenna 163 Dionysius 16 Doissin, Louis 225, 226n4 Bacon, Roger 167 Dorat, Jean 124 Balthasar, Hans von 168, 175 Dowsing, William 176n56 Bartholomeus Anglicus 19 Dumas, Charles 270, 271, 275, 279 Basil of Caesarea 80 Duprat, Antoine 175 Bayley, Walter 167, 170, 171 Bell, Charles 198 Egerton, Stephen 171–173 Bimet, Pierre 230 Elyot, Thomas 267 Biro, Stephanus 230 Erasmus 174n49 Bocccacio, Giovanni 93–99 Evagrius Ponticus -

What the Middle Ages Knew IV

Late Medieval Philosophy Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 http://www.scaruffi.com/know 1 What the Middle Ages knew • Before the Scholastics – The Bible is infallible, therefore there is no need for scientific investigation or for the laws of logic – Conflict between science and religion due to the Christian dogma that the Bible is the truth – 1.Dangerous to claim otherwise – 2.Pointless to search for additional truths – Tertullian (3rd c AD): curiosity no longer necessary because we know the meaning of the world and what is going to happen next ("Liber de Praescriptione Haereticorum") 2 What the Middle Ages knew • Before the Scholastics – Decline of scientific knowledge • Lactantius (4th c AD) ridicules the notion that the Earth could be a sphere ("Divinae Institutiones III De Falsa Sapientia Philosophorum") • Cosmas Indicopleustes' "Topographia Cristiana" (6th c AD): the Earth is a disc 3 What the Middle Ages knew • Before the Scholastics – Plato's creation by the demiurge in the Timaeus very similar to the biblical "Genesis" – Christian thinkers are raised by neoplatonists • Origen was a pupil of Ammonius Sacca (Plotinus' teacher) • Augustine studied Plotinus 4 What the Middle Ages knew • Preservation of classical knowledge – Boethius (6th c AD) translates part of Aristotle's "Organon" and his "Arithmetica" preserves knowledge of Greek mathematics – Cassiodorus (6th c AD) popularizes scientific studies among monks and formalizes education ("De Institutione Divinarum" and "De artibus ac disciplinis liberalium litterarum") with the division of disciplines into arts (grammar, rhetoric, dialectic) – and disiplines (arithmeitc,geometry, music, astronomy) – Isidore of Sevilla (7th c AD) preserves Graeco- Roman knowledge in "De Natura Rerum" and "Origines" 5 What the Middle Ages knew • Preservation of classical knowledge – Bede (8th c AD) compiles an encyclopedia, "De Natura Rerum" – St Peter's at Canterbury under Benedict Biscop (7th c AD) becomes a center of learning – Episcopal school of York: arithmetic, geometry, natural history, astronomy. -

Authority, Reason, and Experience in the Construction of Medieval Natural Knowledge

Assessing the Exotic: Authority, Reason, and Experience in the Construction of Medieval Natural Knowledge by Adam Gwyndaf Garbutt A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto © Copyright by Adam Gwyndaf Garbutt, 2018 ii Assessing the Exotic: Authority, Reason, and Experience in the Construction of Medieval Natural Knowledge Adam Gwyndaf Garbutt Doctor of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto 2018 Abstract This study explores evidence structures in the medieval investigation of nature, particularly the marvelous or exotic nature that exists near the boundaries of natural philosophy. The marvelous, exotic, and unusual are fascinating to both readers and authors, providing windows into the ways in which the evidence structures of reason, authority, and experience were balanced in the assessment, explanation, and presentation of these phenomena. I look at four related works, each engaged with the compilation and presentation of particular information concerning animals and the diversity of the natural world. While these texts are bound together by shared topics and draw from a shared body of ancient and contemporary works, they each speak to different audiences and participate in different genres of literature. I argue that we can see in these works a contextually sensitive approach to the evaluation and presentation of evidence on the part of both the author and the audience. This project also seeks to bridge a gap between the intellectually rigorous medieval texts and works targeted at a wider reading audience that made use of the knowledge base of natural philosophy but were not necessarily produced or consumed within the scholastic context. -

Hunting with Cheetahs at European Courts, from the Origins to the End of a Fashion Thierry Buquet

Hunting with Cheetahs at European Courts, from the Origins to the End of a Fashion Thierry Buquet To cite this version: Thierry Buquet. Hunting with Cheetahs at European Courts, from the Origins to the End of a Fashion. Weber, Nadir; Hengerer, Mark. Animals and Court (Europe, c. 1200–1800), De Gruyter Oldenbourg, pp.17-42, 2020, 978-3-11-054479-4. 10.1515/9783110544794-002. hal-02139428 HAL Id: hal-02139428 https://hal-normandie-univ.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02139428 Submitted on 6 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Thierry Buquet Hunting with Cheetahs at European Courts: From the Origins to the End of a Fashion This document is the post-print version of the following article: Buquet, Thierry, “Hunting with Cheetahs at European Courts: From the Origins to the End of a Fashion”, in Animals and Courts, ed. Mark Hengerer et Nadir Weber, 17-42. Berlin : De Gruyter, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110544794-002. The history of using the cheetah as a hunting auxiliary has been subject of various studies since the beginning of the twentieth century.1 Despite these studies, little has been said about the hunt itself and its evolution at European courts from the beginnings in the thirteenth century up to its decline in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. -

The Journey of a Book

THE JOURNEY OF A BOOK Bartholomew the Englishman and the Properties of Things Map of Europe in c.1230, showing locations significant withinThe Journey of a Book. Approx. indications of the frontiers of Christendom (western and eastern) and Islam, and of the Mongol advance, are based on McEvedy, Colin. The New Penguin Atlas of Medieval History. London: Penguin Books, 1992, pp.73, 77. THE JOURNEY OF A BOOK Bartholomew the Englishman and the Properties of Things Elizabeth Keen Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/journey_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Keen, Elizabeth Joy. Journey of a book : Bartholomew the Englishman and the Properties of things. ISBN 9781921313066 (pbk.). ISBN 9781921313073 (web). 1. Bartholomaeus Anglicus, 13th cent. De proprietatibus rerum. 2. Encyclopedias and dictionaries - Early works to 1600 - History and criticism. 3. Philosophy of nature - Early works to 1800. I. Title. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Cover image: Cambridge University Library Gg. 6. 42. f. 5. St. Francis and Companion used by permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library. Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2007 ANU E Press Table of Contents List of Figures vii Abbreviations ix Acknowledgements xi Chapter 1. Introduction 1 Chapter 2. -

Introduction the Reception of Augustine Is Virtually Synonymous with the Intellectual History of the West

In the Wake of Lombard: The Reception of Augustine in the Early Thirteenth Century Eric Leland Saak Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis Abstract: This article investigates the new attitude toward the reception and use of Augustine in the early thirteenth century as seen in the works of Helinand of Froidmont and Robert Grosseteste. Both scholars were products of the Twelfth Century Renaissance of Augustine, represented in Peter Lombard’s Sentences, the Glossa Ordinaria, and Gratian’s Decretum. Yet both Helinand and Grosseteste reconstructed Augustine’s texts for their own purposes; they did not simply use Augustine as an authority. Detailed and thorough textual analysis reveals that the early thirteenth century was a high point in Augustine’s reception, and one which effected a transformation of how Augustine’s texts were used, a fact [has] often been obscured in the historiographical debates of the relationship between “Augustinianism” and “Aristotelianism.” Moreover, in point to the importance of Helinand’s world chronicle, his Chronicon, this article argues for the importance of compilations as a major source for the intellectual and textual history of the high Middle Ages. Thus, the thirteenth century appears as the bridge between the Augustinian Renaissance of the Twelfth Century, and that of the Fourteenth, making clear the need for further research and highlighting the importance of the early thirteenth century for a thorough understanding of the historical reception of Augustine. Introduction The reception of Augustine