Egglestone Marble in York Churches, 1998

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paper Miller of Old Whose Name Lives On

THE TEESDALE MERCURY. BOLDRON THE LAIR FOLK CLUB L etters WOMEN’S INSTITUTE. KING’S ARMS, STAINDROP, VILLAGE HALL, COTTAGE RAILWAY welcome WHIST DRIVE SHILDON FOLK to a * GRANT NOT in aid of Richardson Hospital. SCENERY SINGALONG, Admission 15p inc. Refreshments. CLAIMED 1 write to endorse all that was 7-30 p.m., Wednesday, 20th June written in your advertisement for Tuesday, 26th June Entry 20p. Readers would be amused by the Cumbrian Coast Railway. It is Mrs Wilson’s comment in her letter EBKTfi a line well worthy of a journey be that to have knocked down my ing made on it with views of little cottage at Whorlton would castles, mountains, cliffs and the LOUIS SMITH MOTORS have been “a nice gesture”. sea all along its length. But there are one or two matters Any revenues from journeys L IM IT E D oi fact which should be stated. The made on it will be welcomed as it discretionary grant which was offer is on the borderline for closure and CALGATE. BARNARD CASTLF ed on this property, has not, in i* this comes about it will deal a fact, been claimed, as it was not devastating blow to the local com TELEPHONE 2129/253* possible to meet all the require munities. I would be delighted to ments. If 1 now obtain the much answer any enquiries. smaller standard grant, 1 shall have OFFER FOR IM M E D IA T E DELIVERY M . H . L . H eywqod. no more than is the right of every M.G.B. -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

“Hancock Coach”

TYNESIDE GROUP - “HANCOCK COACH” Walks Sheet for Sunday 22nd Dec 2019 Barnard Castle via A66 & Greta Bridge Maps OL 31 Return departure 5pm Pick-up Point: Bottom of Claremont Road near the Hancock Museum Return Drop-offs: Claremont Road Car park and Hancock Museum Please observe the following committee rulings: For safety reasons members are expected to stay with the leader throughout the walk Walks leaders: a minimum of 3 people are required on any walk (inc. leader) Walks etiquette: please stay behind or near the leader at all times Please remember and observe the country code PLEASE FASTEN YOUR SEATBELT WHEN THE COACH IS IN MOTION---LEGAL REQUIREMENT PLEASE NOTE: WALKS ARE GRADED AS FOLLOWS: EASY ---- Up to 7 miles with up to 500 feet of climbing, - slow pace LEISURELY ---- 6 to10 miles with up to 1,000 feet of climbing,- leisurely pace MODERATE ---- 8 to13 miles with up to 2,000 feet of climbing, - steady pace STRENUOUS ---- Over 13 miles or over 2,000 feet of climbing, - brisk pace DROP LEADERS GRADE WALK ROUTES May be subject to change due to weather/conditions 1 Hector 13.5 miles. NZ 148091 by Fox Grove , Sorrowfull Hill, Foxberry, Hutton Hall, Langley STRENUOUS Hutton Magna, Wycliffe, Wharlton Bridge, Abbey Bridge, Thorsgill Bridge, Barnard Castle, 2 Susan 9 mile, 600' NZ 113 111 -Smallways Motel, Hutton Magna - Wycliffe - Whorlton Patterson ascents - Mortham - Egglestone Abbey - Abbey Bridge - Demesnes - LEISURELY Barnard Castle 3 Andy Holmes 10ml, NZ086132 Greta Bridge; Tebb Wood; Brignall Mill; NZ035123; 750’ ascents Punder -

Mercury Comment

10th July, 199( THE TEESDALE MERCURY Wednesday, 10th July, 1996 Ballot was good Walkers take a first look at some of the way to assess MERCURY COMMENT public opinion dale's new parish boundary markers Don Day's letter about the Artist Richard Wentworth rectly all along - and indeed it F u ll m arks to Barningham wind farm was Those who organised the bal joined a party of guests on was obvious that if any of the uncharacteristically misin lot on behalf of the people of Wednesday to celebrate the com legal steps had not been com formed. He appears to be Barningham would like to thank pletion of the Marking of the coun cil team pleted an order forcing the j k initial meeting has been unaware that the wind farm is all who took part (indigenous or Parish Boundaries project as travellers to move on would i g to start planning how to currently the subject of not one not), whatever their views. We part of Visual Arts Year. f o r w a y i t not have been issued. j Ag Even wood more attrac- but three separate applications believe it was a worthwhile exer The group included councillors On the day after the case, j by putting in bulbs which and representatives from arts upon which the Parish Meeting cise in democracy which might d e a l t w i t h while some of the caravanners J Jj||produce colourful displays. has been invited to comment. organisations. They were wel prove profitable to other commu were still thinking about ! Coun Raymond Gibson is The first is an application nities faced with making major comed by Teesdale Council's arts the travellers whether or not to go without | -ynnan of a small committee from National Wind Power to decisions affecting their lives. -

Yorkshire Vernacular Buildings Study Group Parish/Township Old County

Yorkshire Vernacular Buildings Study Group ER=East Riding, NR=North Riding, WR=West Riding, D=Durham r=report, p=plan, e=elevation, s=section, d or det=detail, doc=documentation, oral=oral information, site=site map, rf=roof, ph=photograph This list is based upon that compiled by the Vernacular Buildings Studies Group. Additional reports not listed by the VBSG but held by the YAS have been added. The Ref No is the YAS collection reference, and you will need to quote this along with the place name and report number when requesting reports from the archives. All reports are filed under parish or township, where the placename used by the VBRG is different from that it is filed under at the YAS a cross-reference has been added. Parish/Township Old County Report No Building Contents Year of Survey Abbotside NR 416 High Dyke, Lunds r p e 1978 Abbotside NR 1091 Cotterdale, 17 barns r ph 1986 Abbotside, Low NR 916 Foss Ings, bothy r p e d 1983 Abbotside NR 920 Helm r p e d ph 1983 Abbotside NR 1104 Coleby Hall, barns r ph 1986 Acklam ER 1673 Nether Garth r p e ph 2004 Addingham WR 1053 Reynard Ing r p e s l 1986 Addingham WR 1080 Shackleton's Barn r p s 1986 Addingham WR 1081 Stamp Hill r p e s doc 1986 Addingham WR 1082 Paradise Laithe r p s 1986 Addingham WR 1084 Farfield Hall r p s doc 1986 Addingham WR 1193 Overgate Croft r p e 1988 Addingham WR 1237 Manor House r p e rf d 1989 Addingham WR 1244 Lower Cross Bank r p e s d 1990 Addingham WR 1260 16-18 Church Street r p e s d rf 1990 Addingham WR 1262 Parkinson Fold r p e rf 1990 Addingham -

Framlington Longhorsley Lowick Matfen Middleton Milfield Netherton Netherwitton N° L 82 / 70 Journal Officiel Des Communautés Européennes 26

26 . 3 . 84 Journal officiel des Communautés européennes N° L 82 / 67 DIRECTIVE DU CONSEIL du 28 février 1984 relative à la liste communautaire des zones agricoles défavorisées au sens de la directive 75 / 268 / CEE ( Royaume-Uni ) ( 84 / 169 / CEE ) LE CONSEIL DES COMMUNAUTES EUROPEENNES , considérant que les indices suivants , relatifs à la pré sence de terres peu productives visée à l'article 3 para graphe 4 point a ) de la directive 75 / 268 / CEE , ont été retenus pour la détermination de chacune des zones en vu le traité instituant la Communauté économique question : part de la superficie herbagère par rapport à européenne, la superficie agricole utile supérieure à 70 % , densité animale inférieure à l'unité de gros bétail ( UGB ) à l'hectare fourrager et montants des fermages ne dépas sant pas 65 % de la moyenne nationale ; vu la directive 75 / 268 / CEE du Conseil , du 28 avril 1975 , sur l'agriculture de montagne et de certaines zones défavorisées ( 2 ), modifiée en dernier lieu par la directive 82 / 786 / CEE ( 2 ), et notamment son article 2 considérant que les résultats économiques des exploi tations sensiblement inférieurs à la moyenne , visés paragraphe 2 , à l'article 3 paragraphe 4 point b ) de la directive 75 / 268 / CEE , ont été démontrés par le fait que le revenu du travail ne dépasse pas 80 % de la moyenne vu la proposition de la Commission , nationale ; considérant que , pour établir la faible densité de la vu l'avis de l'Assemblée ( 3 ), population visée à l'article 3 paragraphe 4 point c ) de la directive 75 -

The Boundary Committee for England

KEY THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND UNITARY AUTHORITY BOUNDARY PROPOSED ELECTORAL DIVISION BOUNDARY ELECTORAL REVIEW OF COUNTY DURHAM PARISH BOUNDARY PARISH BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH ELECTORAL DIVISION BOUNDARY PARISH WARD BOUNDARY Draft Recommendations for Electoral Division Boundaries in the Unitary Authority of County Durham September 2009 PARISH WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH ELECTORAL DIVISION BOUNDARY WEST AUCKLAND ED PROPOSED ELECTORAL DIVISION NAME Sheet 11 of 12 DENE VALLEY CP PARISH NAME SUNNYDALE PARISH WARD PROPOSED PARISH WARD NAME This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office © Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. The Electoral Commission GD03114G 2009. Scale : 1cm = 0.08000 km Grid interval 1km SHEET 11, MAP 11a Proposed Electoral Divisions in Barnard Castle B SHEET 11, MAP 11b 6 2 7 Proposed Electoral Divisions in Shildon 8 D Cemetery e D Playing n R B EY Allot e B Field B B 6 A e Gdns D 2 c k 8 k i c s 2 e m B E y a V rc I n t R e 8 R l P O e D 8 S d y 6 E a M RURAL R A s O DENE VALLEY CP R Recreation Ground Works R w E iv U a e l HENKNOWLE s r Te i N e e i s K STREATLAM AND STAINTON CP l T l a L DOVECOT HIL w L n R R Golf Course u D a PARISH WARD A R D a Allotment Gardens Clay Pit y d PARISH WARD South Church W D A G e Counden Grange l r t T O e Enterprise Park n O S R iv a O D R eck G B m F N Recn ene s D A N i D L I D U K L Gnd O O -

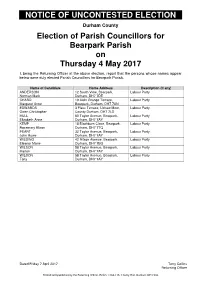

Notice of Uncontested Election

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Durham County Election of Parish Councillors for Bearpark Parish on Thursday 4 May 2017 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Bearpark Parish. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) ANDERSON 12 South View, Bearpark, Labour Party Norman Mark Durham, DH7 7DE CHARD 19 Aldin Grange Terrace, Labour Party Margaret Anne Bearpark, Durham, DH7 7AN EDWARDS 3 Flass Terrace, Ushaw Moor, Labour Party Owen Christopher County Durham, DH7 7LD HULL 60 Taylor Avenue, Bearpark, Labour Party Elizabeth Anne Durham, DH7 7AY KEMP 18 Blackburn Close, Bearpark, Labour Party Rosemary Alison Durham, DH7 7TQ PEART 32 Taylor Avenue, Bearpark, Labour Party John Howe Durham, DH7 7AY WILDING 42 Ritson Avenue, Bearpark, Labour Party Eleanor Marie Durham, DH7 7BG WILSON 58 Taylor Avenue, Bearpark, Labour Party Marion Durham, DH7 7AY WILSON 58 Taylor Avenue, Bearpark, Labour Party Tony Durham, DH7 7AY Dated Friday 7 April 2017 Terry Collins Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Room 1/104-115, County Hall, Durham, DH1 5UL NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Durham County Election of Parish Councillors for Bishop Middleham Parish on Thursday 4 May 2017 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Bishop Middleham Parish. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) COOKE 5 High Road, Bishop Middleham, -

Historical Journey Along the River Tees and Its Tributaries

Historical Journey along the River Tees and its Tributaries Synopsis The document describes a virtual journey along the River Tees beginning at its source; the perspective is as much historical as descriptive of the current scene. Where significant tributaries join the river, they also are tracked back to their start-points. Particular attention is paid to bridges and watermills because of their intimate associations with the rivers, but nearby buildings, both religious and secular are also given attention. Some people have been specially important to developments associated with the river, and brief biographical notes are provided for them. Finally, I would stress that this is very much a personal account dealing with facets of interest to me during the 30 years or so that I spent living and working near the River Tees. Document Navigation I do not provide either a contents list, or an index, but to aid navigation through the document I give here page numbers, on which some places appear first in the text. Place Page No. Source of the River Tees 3 Middleton-in-Teesdale 5 Barnard Castle 9 River Greta confluence 15 Piercebridge 18 Darlington 20 Yarm 28 River Leven confluence 35 Stockton-on-Tees 36 Middlesbrough 37 Saltburn-by-the-Sea 46 Hartlepool 48 There is a sketch map of the river and the main tributaries in Table T1 on Page 50. The Bibliography is on Page 52. 1 River Tees and its Tributaries The River Tees flows for 135km, generally west to east from its source on the slopes of Crossfell, the highest Pennine peak, to the North Sea between Redcar and Hartlepool. -

Ipcoi JOB CLUB

THE TEESDALE MERCURY Wednesday, 21st November, 2001 T Wednesday OBITUARY: Newton Hutchinson Sweet smell of success! iPcoi A COSMETICS manager from Startforth has been enjoying socialising with the rich and G a m e k e e p e r famous at a recent awards din ner. w Shona Robinson, who works A tribute by for Virgin Cosmetics, was delighted when she qualified o f t h e Richard Watson along with 40 others out of 8,000 nationwide to attend the 2001 Branson High Flyer Club Annual Awards dinner in London. “It was beyond my wildest o l d s c h o o l dreams,” said Shona, who was rewarded for reaching her THE funeral service of Mr 1953, he went as head keeper Diamond level of the Branson Newton Hutchinson of to Selaby for the Rt. Hon Mr High Flyer Club. “Diamond HOW do you Piercebridge, who died on 5 Vane, now Lord Barnard. He level means I have reached unique charschi November, took place in St remained there till 1979 when £40,000 worth of sales in the that makes it Mary’s Church on Monday, he retired. last 12 months,” she explained. to live? November 12, followed by fam Lord Barnard told the Shona moved to Barnard Simple! Yc ily cremation. M e r c u r y : “Newton Hutch Castle a couple of years ago and experts - the A widower since 1986, he inson came to Selaby as a knew no-one: “I was a self- there. had five children, Mrs Bradley Game Keeper in 1953, and left employed beauty therapist and ABOVE: Shona Robinson with Sir Richard Branson at the That is wl from Falkirk, Mrs Weighell when he retired in 1979 to knew no-one in the area, so it 2001 Awards Dinner. -

County Durham Landscape Character Assessment

THE DURHAM LANDSCAPE The Durham Landscape Physical influences Human influences The modern landscape Perceptions of the landscape Designated landscapes 7 THE DURHAM LANDSCAPE PHYSICAL INFLUENCES Physical influences The Durham landscape is heavily influenced by the character of its underlying rocks, by the effects of erosion and deposition in the last glacial period, and by the soils that have developed on the post-glacial terrain under the influence of the climatic conditions that have prevailed since then. Geology The geology of the county is made up of gently folded Carboniferous rocks dipping towards the east where they are overlain by younger Permian rocks. In the west, thinly bedded sandstones, mudstones and limestones of the Carboniferous Limestone series (Dinantian period) outcrop in the upper dales and are overlain by similar rocks of the Millstone Grit series (Namurian period), which form most of the upland fells. The alternating strata of harder and softer rocks give a stepped profile to many dale sides and distinctive flat-topped summits to the higher fells. Older Ordovician rocks, largely made up of pale grey mudstones or slates showing a degree of metamorphism, occur in a small inlier in upper Teesdale. The rocks of the Millstone Grit series are overlain in the north by the Lower and Middle Coal Measures (Westphalian period) which fall from the upland fringes to the lowlands of the Wear and dip under the Permian Limestone in the east. The soft and thinly bedded strata of coal, sandstone and mudstone have been eroded to form gently sloping valley sides where occasional steeper bluffs mark thicker beds of harder sandstones. -

Norbeck to Clow Beck at Croft

Norbeck to Clow Beck at Croft In Barningham we all know the Norbeck; it’s the dog-leg bridge below Low Lane on the way to Greta Bridge. It is our beck, and it takes away our effluent from the treatment works below Barningham House farm. But it becomes Hutton Beck as it flows through Hutton Magna and has many different names on its course to the Tees. I recently came across a reference to Aldebrough Beck, “rising near Eppleby “ and thought, “No! that is our Norbeck and it rises on Barningham Moor.” Left : Osmaril Gill on a bright Autumn morning Searching the OS map I can locate 13 springs on Barningham Moor that feed our Norbeck; there will be many more springs feeding it on its way to the Tees. Osmaril has clear connections with Neolithic habitations and is very atmosheric. Right: Croft Bridge over the Tees Our Norbeck ends up as the Clow Beck and reaches the Tees some half-mile above Croft Bridge. This bridge carried the old Great North Road from Yorkshire into Durham until the advent of the motor age. Geology, Climate, Landform, Landscape and People The geology of the area developed over millions of years and played an important role in developing the landscape we are familiar with; but the changing climate over the countless centuries have also left their mark. This is especially true of the ice ages, especially the last one; mountains were shaved down, river courses changed and whole areas filled up with boulder clay and other alluvium. But man has also had a significant role in creating the place where we live.