Story of Jose Rizal Craig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BINONDO FOOD TRIP (4 Hours)

BINONDO FOOD TRIP (4 hours) Eat your way around Binondo, the Philippines’ Chinatown. Located across the Pasig River from the walled city of Intramuros, Binondo was formally established in 1594, and is believed to be the oldest Chinatown in the world. It is the center of commerce and trade for all types of businesses run by Filipino-Chinese merchants, and given the historic reach of Chinese trading in the Pacific, it has been a hub of Chinese commerce in the Philippines since before the first Spanish colonizers arrived in the Philippines in 1521. Before World War II, Binondo was the center of the banking and financial community in the Philippines, housing insurance companies, commercial banks and other financial institutions from Britain and the United States. These banks were located mostly along Escólta, which used to be called the "Wall Street of the Philippines". Binondo remains a center of commerce and trade for all types of businesses run by Filipino- Chinese merchants and is famous for its diverse offerings of Chinese cuisine. Enjoy walking around the streets of Binondo, taking in Tsinoy (Chinese-Filipino) history through various Chinese specialties from its small and cozy restaurants. Have a taste of fried Chinese Lumpia, Kuchay Empanada and Misua Guisado at Quick Snack located along Carvajal Street; Kiampong Rice and Peanut Balls at Café Mezzanine; Kuchay Dumplings at Dong Bei Dumplings and the growing famous Beef Kan Pan of Lan Zhou La Mien. References: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binondo,_Manila TIME ITINERARY 0800H Pick-up -

Colonial Contractions: the Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946

Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Vicente L. Rafael Subject: Southeast Asia, Philippines, World/Global/Transnational Online Publication Date: Jun 2018 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.268 Summary and Keywords The origins of the Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histories of three empires that swept onto its shores: the Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese. This history makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation- states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power rela tionships. Such shifts have included not just regime change but also social revolution. The modernity of the modern Philippines is precisely the effect of the contradictory dynamic of imperialism. The Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese colonial regimes, as well as their postcolonial heir, the Republic, have sought to establish power over social life, yet found themselves undermined and overcome by the new kinds of lives they had spawned. It is precisely this dialectical movement of empires that we find starkly illumi nated in the history of the Philippines. Keywords: Philippines, colonialism, empire, Spain, United States, Japan The origins of the modern Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histo ries of three empires: Spain, the United States, and Japan. This background makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation-states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power relationships. -

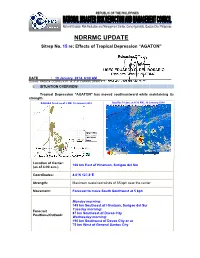

Nd Drrm C Upd Date

NDRRMC UPDATE Sitrep No. 15 re: Effects of Tropical Depression “AGATON” Releasing Officer: USEC EDUARDO D. DEL ROSARIO Executive Director, NDRRMC DATE : 19 January 2014, 6:00 AM Sources: PAGASA, OCDRCs V,VII, IX, X, XI, CARAGA, DPWH, PCG, MIAA, AFP, PRC, DOH and DSWD I. SITUATION OVERVIEW: Tropical Depression "AGATON" has moved southeastward while maintaining its strength. PAGASA Track as of 2 AM, 19 January 2014 Satellite Picture at 4:32 AM., 19 January 2014 Location of Center: 166 km East of Hinatuan, Surigao del Sur (as of 4:00 a.m.) Coordinates: 8.0°N 127.8°E Strength: Maximum sustained winds of 55 kph near the center Movement: Forecast to move South Southwest at 5 kph Monday morninng: 145 km Southeast of Hinatuan, Surigao del Sur Tuesday morninng: Forecast 87 km Southeast of Davao City Positions/Outlook: Wednesday morning: 190 km Southwest of Davao City or at 75 km West of General Santos City Areas Having Public Storm Warning Signal PSWS # Mindanao Signal No. 1 Surigao del Norte (30-60 kph winds may be expected in at Siargao Is. least 36 hours) Surigao del Sur Dinagat Province Agusan del Norte Agusan del Sur Davao Oriental Compostela Valley Estimated rainfall amount is from 5 - 15 mm per hour (moderate - heavy) within the 300 km diameter of the Tropical Depression Tropical Depression "AGATON" will bring moderate to occasionally heavy rains and thunderstorms over Visayas Sea travel is risky over the seaboards of Luzon and Visayas. The public and the disaster risk reduction and management councils concerned are advised to take appropriate actions II. -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AURORA

2010 Census of Population and Housing Aurora Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AURORA 201,233 BALER (Capital) 36,010 Barangay I (Pob.) 717 Barangay II (Pob.) 374 Barangay III (Pob.) 434 Barangay IV (Pob.) 389 Barangay V (Pob.) 1,662 Buhangin 5,057 Calabuanan 3,221 Obligacion 1,135 Pingit 4,989 Reserva 4,064 Sabang 4,829 Suclayin 5,923 Zabali 3,216 CASIGURAN 23,865 Barangay 1 (Pob.) 799 Barangay 2 (Pob.) 665 Barangay 3 (Pob.) 257 Barangay 4 (Pob.) 302 Barangay 5 (Pob.) 432 Barangay 6 (Pob.) 310 Barangay 7 (Pob.) 278 Barangay 8 (Pob.) 601 Calabgan 496 Calangcuasan 1,099 Calantas 1,799 Culat 630 Dibet 971 Esperanza 458 Lual 1,482 Marikit 609 Tabas 1,007 Tinib 765 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Aurora Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Bianuan 3,440 Cozo 1,618 Dibacong 2,374 Ditinagyan 587 Esteves 1,786 San Ildefonso 1,100 DILASAG 15,683 Diagyan 2,537 Dicabasan 677 Dilaguidi 1,015 Dimaseset 1,408 Diniog 2,331 Lawang 379 Maligaya (Pob.) 1,801 Manggitahan 1,760 Masagana (Pob.) 1,822 Ura 712 Esperanza 1,241 DINALUNGAN 10,988 Abuleg 1,190 Zone I (Pob.) 1,866 Zone II (Pob.) 1,653 Nipoo (Bulo) 896 Dibaraybay 1,283 Ditawini 686 Mapalad 812 Paleg 971 Simbahan 1,631 DINGALAN 23,554 Aplaya 1,619 Butas Na Bato 813 Cabog (Matawe) 3,090 Caragsacan 2,729 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and -

PHILIPPINES Manila GLT Site Profile

PHILIPPINES Manila GLT Site Profile AZUSA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY GLOBAL LEARNING TERM 626.857.2753 | www.apu.edu/glt 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO MANILA ................................................... 3 GENERAL INFORMATION ........................................................ 5 CLIMATE AND GEOGRAPHY .................................................... 5 DIET ............................................................................................ 5 MONEY ........................................................................................ 6 TRANSPORTATION ................................................................... 7 GETTING THERE ....................................................................... 7 VISA ............................................................................................. 8 IMMUNIZATIONS ...................................................................... 9 LANGUAGE LEARNING ............................................................. 9 HOST FAMILY .......................................................................... 10 EXCURSIONS ............................................................................ 10 VISITORS .................................................................................. 10 ACCOMODATIONS ................................................................... 11 SITE FACILITATOR- GLT PHILIPPINES ................................ 11 RESOURCES ............................................................................... 13 NOTE: Information is subject to -

Philippine Port Authority Contracts Awarded for CY 2018

Philippine Port Authority Contracts Awarded for CY 2018 Head Office Project Contractor Amount of Project Date of NOA Date of Contract Procurement of Security Services for PPA, Port Security Cluster - National Capital Region, Central and Northern Luzon Comprising PPA Head Office, Port Management Offices (PMOs) of NCR- Lockheed Global Security and Investigation Service, Inc. 90,258,364.20 27-Nov-19 23-Dec-19 North, NCR-South, Bataan/Aurora and Northern Luzon and Terminal Management Offices (TMO's) Ports Under their Respective Jurisdiction Proposed Construction and Offshore Installation of Aids to Marine Navigation at Ports of JARZOE Builders, Inc./ DALEBO Construction and General. 328,013,357.76 27-Nov-19 06-Dec-19 Estancia, Iloilo; Culasi, Roxas City; and Dumaguit, New Washington, Aklan Merchandise/JV Proposed Construction and Offshore Installation of Aids to Marine Navigation at Ports of Lipata, Goldridge Construction & Development Corporation / JARZOE 200,000,842.41 27-Nov-19 06-Dec-19 Culasi, Antique; San Jose de Buenavista, Antique and Sibunag, Guimaras Builders, Inc/JV Consultancy Services for the Conduct of Feasibility Studies and Formulation of Master Plans at Science & Vision for Technology, Inc./ Syconsult, INC./JV 26,046,800.00 12-Nov-19 16-Dec-19 Selected Ports Davila Port Development Project, Port of Davila, Davila, Pasuquin, Ilocos Norte RCE Global Construction, Inc. 103,511,759.47 24-Oct-19 09-Dec-19 Procurement of Security Services for PPA, Port Security Cluster - National Capital Region, Central and Northern Luzon Comprising PPA Head Office, Port Management Offices (PMOs) of NCR- Lockheed Global Security and Investigation Service, Inc. 90,258,364.20 23-Dec-19 North, NCR-South, Bataan/Aurora and Northern Luzon and Terminal Management Offices (TMO's) Ports Under their Respective Jurisdiction Rehabilitation of Existing RC Pier, Port of Baybay, Leyte A. -

Laguna Lake, the Philippines: Industrial Contamination Hotspots

Laguna Lake, The Philippines: industrial contamination hotspots Iryna Labunska, Kevin Brigden, Paul Johnston Greenpeace Research Laboratories Technical Note 06/2011 June 2011 1. Introduction Contamination of natural water resources by discharges from the industrial sector in the Philippines continues to be a significant problem. In 2007, Greenpeace launched the Water Patrol to document the impact of water pollution on local communities in the Philippines. Within the framework of this project, several industrial sites located around Laguna Lake were visited in July 2010. During these visits, samples of wastewater discharges into creeks and tributaries of Laguna Lake and corresponding sediment or soil samples were collected. The sites which were chosen for investigation in this study were those accommodating potentially polluting facilities in the area. The selection of the facilities was based on the following criteria: facility operations were thought to involve the use of toxic chemicals; the facility discharged wastewater directly into Laguna Lake or one of its tributaries; in some cases, the facility had been previously identified by government agencies as a polluting industry and listed in the black or red lists by the Laguna Lake Development Authority or the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. Four facilities located to the south-east of Laguna Lake were targeted in the current study: Mayer Textile; Philippine Industrial Sealants and Coatings Corporation (PIS); TNC Chemicals; Carmelray 1 Industrial Park. Wastewater is discharged from these facilities into the San Juan River and the San Cristobal River. Two other target facilities were located to the north of Laguna Lake - Hansson Papers and Litton Mills. -

Death by Garrote Waiting in Line at the Security Checkpoint Before Entering

Death by Garrote Waiting in line at the security checkpoint before entering Malacañang, I joined Metrobank Foundation director Chito Sobrepeña and Retired Justice Rodolfo Palattao of the anti-graft court Sandiganbayan who were discussing how to inspire the faculty of the Unibersidad de Manila (formerly City College of Manila) to become outstanding teachers. Ascending the grand staircase leading to the ceremonial hall, I told Justice Palattao that Manuel Quezon never signed a death sentence sent him by the courts because of a story associated with these historic steps. Quezon heard that in December 1896 Jose Rizal's mother climbed these steps on her knees to see the governor-general and plead for her son's life. Teodora Alonso's appeal was ignored and Rizal was executed in Bagumbayan. At the top of the stairs, Justice Palattao said "Kinilabutan naman ako sa kinuwento mo (I had goosebumps listening to your story)." Thus overwhelmed, he missed Juan Luna's Pacto de Sangre, so I asked "Ilan po ang binitay ninyo? (How many people did you sentence to death?)" "Tatlo lang (Only three)", he replied. At that point we were reminded of retired Sandiganbayan Justice Manuel Pamaran who had the fearful reputation as The Hanging Judge. All these morbid thoughts on a cheerful morning came from the morbid historical relics I have been contemplating recently: a piece of black cloth cut from the coat of Rizal wore to his execution, a chipped piece of Rizal's backbone displayed in Fort Santiago that shows where the fatal bullet hit him, a photograph of Ninoy Aquino's bloodstained shirt taken in 1983, the noose used to hand General Yamashita recently found in the bodega of the National Museum. -

Chapter 2. Geophysical Environment

Chapter 2. Geophysical Environment Geographical Location dated February 08, 2012 and RA 10161 dated April 10, Cavite is part of the Philippines’ largest island, the Luzon 2012, respectively, and the newly converted City of Gen. Peninsula. Found in the southern portion, Cavite belongs Trias through Republic Act 10675 which was signed into to Region IV-A or the CALABARZON region. The provinces law on August 19, 2015 and ratified on December 12, of Batangas in the south, Laguna in the east, Rizal in the 2015. northeast, Metro Manila and Manila Bay in the north, and West Philippine Sea in the west bounds the Province. Presidential Decree 1163 declared the City of Imus is the de jure provincial capital, and Trece Martires City is the Cavite has the GPS coordinates of 14.2456º N, 120.8786º E. Its proximity to Metro Manila gives the province a de facto seat of the provincial government. significant edge in terms of economic development. In addition, in 1909, during the American regime, Governor-General W. Cameron Forbes issued the Executive Order No. 124, declaring Act No. 1748 that annexed Corregidor and the Islands of Caballo (Fort Hughes), La Monja, El Fraile (Fort Drum), Sta. Amalia, Carabao (Fort Frank) and Limbones, as well as all waters and detached rocks surrounding them to the City of Cavite. These are now major tourist attractions of the province. The municipality of Ternate also has Balut Island. Table 2.1 Number of barangays by city/municipality and congressional district; Province of Cavite: 2018 Number of City/Municipality Barangays 1st District 143 Cavite City 84 Kawit 23 Political Boundaries Noveleta 16 Rosario 20 The province of Cavite has well-defined political 2nd District 73 subdivisions. -

The Honorees of Rizal

THE HONOREES OF RIZAL By Sir Eliseo B. Barja, KOR Knight of Rizal, Malaya Chapter The national hero of the Philippines, Dr. Jose Rizal, great as he was, did not fail to give honor to others he believed deserved their due. Unlike other great men in history, his acts and writings reveal how he placed his honorees’ names in high pedestals of accolade. These people were his own race, which he always maintained as equal to or at par with other races. Father: Don Francisco Mercado Rizal First of these honorees was his own father, Don Francisco Mercado Rizal. Dr. Rizal did not simply praise his father; in fact he was so modest in giving praises. He affectionately called him “a model of fathers” as he was quoted in his biography by historian Gregorio F. Zaide. But it was evident in his writings while he was traveling that he always wanted that his parents be taken care of. Then In his last letter to his brother Paciano, dated December 29, 1896, a day before his execution, he said: “My dear Brother, Now I am about to die, and it is to you that I dedicate my last lines, to tell you how sad I am to leave you alone in life, burdened with the weight of the family and our old parents… Tell our father that I remember him! And how I remember my whole childhood, of his affection and his love. Ask him to forgive me for the pain that I have unwillingly caused him.” And on the following day, December 30, just two hours before his execution, Rizal wrote his father in part: “My beloved Father, Pardon me for the pain with which I repay you for your sorrows and sacrifices for my education. -

Tour Descriptions Tour: Combination City of Old

TOUR DESCRIPTIONS TOUR: COMBINATION CITY OF OLD & NEW MANILA DURATION: FULL DAY (8 HOURS) This tour is an orientation tour that features the old and new Manila. This tour is designed to let you have a feel of Manila’s old lifestyle and to let you take a peak on Manila’s ultra - modern metropolises. A tour that will have you traversed from Manila’s historic past to the present modern and emerging urban centers. Come! Experience the FUN and friendliness in one of the most hospitable cities in Asia. In the first part of the tour, visit Rizal Park and Monument-One of Manila’s most important landmark and pay homage to our national hero Dr. Jose Rizal. Proceed to Intramuros - walled city of Manila, where the seat of government during the Spanish Colonial Period is situated. Visit Fort Santiago - oldest and most important fortification during the Spanish rule, Manila Cathedral - seat of the archdiocese of Manila, San Agustin Church - Old Catholic Church in the Philippines and UNESCO world heritage site and Casa Manila-museum that features Spanish era ilustrado house. Lunch at local restaurant. After lunch we proceed to the second part of the tour. Visit Manila American Cemetery, pay homage to WWII heroes, pass by Forbes Park - Manila’s millionaires’ row. And proceed on a driving tour of Bonifacio Global City - Manila’s emerging ultra-modern urban center. We then proceed to Ayala Malls in Makati City for free time shopping. Rizal Park and Monument Fort Santiago, Manila TOUR: SCENIC TAGAYTAY RIDGE DURATION: FULL DAY (8-10 HOURS) Only a few hours’ drive from Manila is the refreshing wisp of a city and capture the panoramic & most splendid views of the Taal Volcano – the world’s smallest, while the cool breeze offer a brief escape from the heat of Manila – all from the picturesque city of Tagaytay. -

The Development of the Philippine Foreign Service

The Development of the Philippine Foreign Service During the Revolutionary Period and the Filipino- American War (1896-1906): A Story of Struggle from the Formation of Diplomatic Contacts to the Philippine Republic Augusto V. de Viana University of Santo Tomas The Philippine foreign service traces its origin to the Katipunan in the early 1890s. Revolutionary leaders knew that the establishment of foreign contacts would be vital to the success of the objectives of the organization as it struggles toward the attainment of independence. This was proven when the Katipunan leaders tried to secure the support of Japanese and German governments for a projected revolution against Spain. Some patriotic Filipinos in Hong Kong composed of exiles also supported the Philippine Revolution.The organization of these exiled Filipinos eventually formed the nucleus of the Philippine Central Committee, which later became known as the Hong Kong Junta after General Emilio Aguinaldo arrived there in December 1897. After Aguinaldo returned to the Philippines in May 1898, he issued a decree reorganizing his government and creating four departments, one of which was the Department of Foreign Relations, Navy, and Commerce. This formed the basis of the foundation of the present Department of Foreign Affairs. Among the roles of this office was to seek recognition from foreign countries, acquire weapons and any other needs of the Philippine government, and continue lobbying for support from other countries. It likewise assigned emissaries equivalent to today’s ambassadors and monitored foreign reactions to the developments in the Philippines. The early diplomats, such as Felipe Agoncillo who was appointed as Minister Plenipotentiary of the revolutionary government, had their share of hardships as they had to make do with meager means.