[Inter]Sections 23 (2020): 17-35

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fighting for Women Existence in Popular Espionage Movies Salt (2010) and Zero Dark Thirty (2012)

Benita Amalina — Fighting For Women Existence in Popular Espionage Movies Salt (2010) and Zero Dark Thirty (2012) FIGHTING FOR WOMEN EXISTENCE IN POPULAR ESPIONAGE MOVIES SALT (2010) AND ZERO DARK THIRTY (2012) Benita Amalina [email protected] Abstract American spy movies have been considered one of the most profitable genre in Hollywood. These spy movies frequently create an assumption that this genre is exclusively masculine, as women have been made oblivious and restricted to either supporting roles or non-spy roles. In 2010 and 2012, portrayal of women in spy movies was finally changed after the release of Salt and Zero Dark Thirty, in which women became the leading spy protagonists. Through the post-nationalist American Studies perspective, this study discusses the importance of both movies in reinventing women’s identity representation in a masculine genre in response to the evolving American society. Keywords: American women, hegemony, representation, Hollywood, movies, popular culture Introduction The financial success and continuous power of this industry implies that there has been The American movie industry, often called good relations between the producers and and widely known as Hollywood, is one of the main target audience. The producers the most powerful cinematic industries in have been able to feed the audience with the world. In the more recent data, from all products that are suitable to their taste. Seen the movies released in 2012 Hollywood from the movies’ financial revenues as achieved $ 10 billion revenue in North previously mentioned, action movies are America alone, while grossing more than $ proven to yield more revenue thus become 34,7 billion worldwide (Kay, 2013). -

ZERO DARK THIRTY an Original Screenplay by Mark Boal October 3

ZERO DARK THIRTY An Original Screenplay by Mark Boal October 3, 2011 all rights reserved FROM BLACK, VOICES EMERGE-- We hear the actual recorded emergency calls made by World Trade Center office workers to police and fire departments after the planes struck on 9/11, just before the buildings collapsed. TITLE OVER: SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 We listen to fragments from a number of these calls...starting with pleas for help, building to a panic, ending with the caller's grim acceptance that help will not arrive, that the situation is hopeless, that they are about to die. CUT TO: TITLE OVER: TWO YEARS LATER INT. BLACK SITE - INTERROGATION ROOM DANIEL I own you, Ammar. You belong to me. Look at me. This is DANIEL STANTON, the CIA's man in Islamabad - a big American, late 30's, with a long, anarchical beard snaking down to his tattooed neck. He looks like a paramilitary hipster, a punk rocker with a Glock. DANIEL (CONT'D) (explaining the rules) If you don't look at me when I talk to you, I hurt you. If you step off this mat, I hurt you. If you lie to me, I'm gonna hurt you. Now, Look at me. His prisoner, AMMAR, stands on a decaying gym mat, surrounded by four GUARDS whose faces are covered in ski masks. Ammar looks down. Instantly: the guards rush Ammar, punching and kicking. DANIEL (CONT'D) Look at me, Ammar. Notably, one of the GUARDS wearing a ski mask does not take part in the beating. 2. EXT. -

Zero Dark Thirty Error

Issue 7 | Movie: A Journal of Film Criticism | 23 troop carrier with no clear sense of destination, speaks again understated performances further serve to create what might as much to a national as a personal loss of purpose, afer the be described as a reality afect. quest is over. Te 9/11 sequence ofers an extreme version of the real- Te flm’s epilogue has received considerable critical atten- ist aesthetic and the rejection of spectacle. From the second tion1; the prologue less so. And where critics do mention it, plane hitting the tower, to the falling man, to the rubble details are ofen misremembered. In an interview with Kyle of ground zero, there are any number of iconic images the Buchanan, screenwriter Mark Boal refects on the difculties flmmakers might have selected to represent the destruction of writing the ‘opening scene’ of Zero Dark Tirty (2013). Te wrought by the attacks. However, what such images have in scene he is referring to in this discussion, however, is the infa- common, what potentially makes them efective as a form of mous torture scene that begins the narrative proper (to which cultural shorthand, also renders them problematic in terms I will return). It is as if he has momentarily forgotten the scene of eliciting a fresh response – and certainly in terms of the Intimacy, ‘truth’ and the gaze: that precedes it in the original shooting script as well as the slow-burn, reality afect. Teir very familiarity can render flm. Given this oversight by the writer himself, it is under- such images hackneyed and over-determined. -

Spring 07 Acg R5:Flame Fall AR 2004 Fq4.Qxd 7/12/07 4:18 PM Page 1

Flame Spring 07 acg r5:Flame Fall AR 2004 fQ4.qxd 7/12/07 4:18 PM Page 1 Volume 8, Number 1 Spring 2007 the FlameThe Magazine of Claremont Graduate University “9-1-1, what’s the nature of your emergency?” Flame Spring 07 acg r5:Flame Fall AR 2004 fQ4.qxd 7/12/07 4:18 PM Page 2 theFlame The Magazine of Claremont Graduate University inin aa universityuniversity dedicateddedicated Spring 2007 InvestInvest Volume 8, Number 1 The Flame is published by toto unboundedunbounded thinkingthinking andand excellence.excellence. Claremont Graduate University 150 East Tenth Street, Claremont, CA 91711 ©2007 by Claremont Graduate University Director of University Communications Esther Wiley Managing Editor Geri Silveira Art Director Susan Guntner, Swan Graphics News Editor Nikolaos Johnson Online Editor Derik Casper Editorial Contributors Brendan Babish Mandy Bennett Deborah Haar Clark Joseph Coombe Dean Gerstein Steven K. Wagner Director of Alumni and Donor Relations Joy Kliewer, PhD, ’97 Alumnotes Managing Editor Monika Moore Distribution Manager Mandy Bennett Photographers Kevin Burke Marc Campos Gabriel Fenoy Kimi Kolba Fred Prouser/Reuters/Corbis in a university dedicated Tom Zasadzinski Invest Claremont Graduate University, founded in 1925, focuses exclusively on graduate-level study. It is a to unbounded thinking and excellence. member of The Claremont Colleges, a consortium of seven independent Your gift supports: Annual Giving institutions. President and University Professor Robert Klitgaard Office of Advancement World-class teaching and distinguishedYour gift supports: Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs research that cultivates future leaders 165 E. Tenth St. Yi Feng World-class teaching and distinguished research that cultivate future whose talents enrich the lives of others. -

Woman As a Category / New Woman Hybridity

WiN: The EAAS Women’s Network Journal Issue 1 (2018) The American Woman Warrior: A Transnational Feminist Look at War, Imperialism, and Gender Agnieszka Soltysik Monnet ABSTRACT: This article examines the issue of torture and spectatorship in the film Zero Dark Thirty through the question of how it deploys gender ideologically and rhetorically to mediate and frame the violence it represents. It begins with the controversy the film provoked but focuses specifically on the movie’s representational and aesthetic techniques, especially its self-awareness about being a film about watching torture, and how it positions its audience in relation to these scenes. Issues of spectator identification, sympathy, interpellation, affect (for example, shame) and genre are explored. The fact that the main protagonist of the film is a woman is a key dimension of the cultural work of the film. I argue that the use of a female protagonist in this film is part of a larger trend in which the discourse of feminism is appropriated for politically conservative and antifeminist ends, here the tacit justification of the legally murky world of black sites and ‘enhanced interrogation techniques.’ KEYWORDS: gender; women’s studies; torture; war on terror; Abu Ghraib; spectatorship; neoliberalism; Angela McRobbie; Some of you will recognize my title as alluding to Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior (1975), a fictionalized autobiography in which she evokes the fifth-century Chinese legend of a girl who disguises herself as a man in order to go to war in the place of her frail old father. Kingston’s use of this legend is credited with having popularized the story in the United States and paved the way for the 1998 Disney adaptation. -

Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty Or a Visionary?

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Honors Senior Theses/Projects Student Scholarship 6-1-2016 Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary? Courtney Richardson Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Richardson, Courtney, "Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary?" (2016). Honors Senior Theses/Projects. 107. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses/107 This Undergraduate Honors Thesis/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Theses/Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary? By Courtney Richardson An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Western Oregon University Honors Program Dr. Shaun Huston, Thesis Advisor Dr. Gavin Keulks, Honors Program Director Western Oregon University June 2016 2 Acknowledgements First I would like to say a big thank you to my advisor Dr. Shaun Huston. He agreed to step in when my original advisor backed out suddenly and without telling me and really saved the day. Honestly, that was the most stressful part of the entire process and knowing that he was available if I needed his help was a great relief. Second, a thank you to my Honors advisor Dr. -

Agnieszka Lions for Lambs TRACK CHANGES and COMMENTS April 17

AFGHANISTAN AGNIESZKA SOLTYSIK MONNET Lions for Lambs (2007): Ambivalent Memorialization and Melodrama Lions for Lambs (2007) is a film about the importance of historical memory. Through three interwoven stories told in real time (90 minutes), the film suggests that the wars in the Middle East (the film’s combat scene takes place in Afghanistan) are repeating many of the mistakes of the Vietnam War. Memory and memorialization are thus central to the film’s concerns, through a dual agenda of reminding viewers of the lessons of the Vietnam era as well as commemorating the soldiers who are being once more exposed to danger for murky political goals. Just as the word “memorialize” has two meanings which sometimes pull in opposite directions (to preserve the memory of and to commemorate, which can be understood in either a neutral or a more celebratory sense), so do the film’s objectives end up pulling in opposite directions. On the one hand, the film wishes to offer a critical perspective on the war in Afghanistan, arguing that the military approach alone will never accomplish its stated objectives and can only lead to the deaths of more young soldiers such as the protagonists of 1 the movie, Ernest (Michael Pena) and Arian (Derek Luke), two college students, a Mexican American and an African American. On the other hand, the film wants to honor the service and sacrifice of these soldiers, in keeping with the current climate of reverence to military personnel,1 and therefore presents their deaths in a highly melodramatic and quasi-religious aesthetic frame which sits uneasily with the critical and questioning thrust of the film. -

0927 Daily Pennsylvanian

Parkway M. Soccer falls Movin’ on up in double-OT Past 40th Street — the Penntrification of West Philly. party See Sports | Back Page See 34th Street Magazine See page 4 The Independent Student Newspaper of the University of Pennsylvania ◆ Founded 1885 THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 2007 dailypennsylvaniapennsylvan ian.com PHILADELPHIA | VOL. CXXIII, NO. 84 U. City: Newest dining destination? Penn InTouch changes far on the horizon While student groups call for Penn InTouch improvements, changes likely to take months By REBECCA KAPLAN many believe needs a major Staff Writer overhaul. [email protected] Regina Koch , the IT Techni- Any senior hoping for a sim- cal Director for Student Regis- ple, streamlined class-registra- tration and Financial Services, tion system should stop holding said improving Penn InTouch their breath: Penn InTouch will now is an official project. not be updated this year. “We have to replace some But there is still hope for of the technology because the freshmen, sophomores and ju- systems are 15 years old,” she niors, who will likely see a big said. improvement to the system by Wharton senior Alex Flamm , the time they graduate. the Undergraduate Assembly Last Tuesday, members of representative spearheading the Undergraduate Assembly, the campaign for Penn InTouch Student Financial Services and change, said SFS and ISC are Information Systems and Com- planning a large change sooner puting met to find new ways to than anticipated. improve Penn InTouch, the on- line organization system that See INTOUCH, page 3 Sundance Kid set Staci Hou & Kien Lam/DP File Photos for film screening Top: Morimoto, a Japanese restaurant in Center City owned by Steven Starr. -

Announcing a VIEW from the BRIDGE

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE “One of the most powerful productions of a Miller play I have ever seen. By the end you feel both emotionally drained and unexpectedly elated — the classic hallmark of a great production.” - The Daily Telegraph “To say visionary director Ivo van Hove’s production is the best show in the West End is like saying Stonehenge is the current best rock arrangement in Wiltshire; it almost feels silly to compare this pure, primal, colossal thing with anything else on the West End. A guileless granite pillar of muscle and instinct, Mark Strong’s stupendous Eddie is a force of nature.” - Time Out “Intense and adventurous. One of the great theatrical productions of the decade.” -The London Times DIRECT FROM TWO SOLD-OUT ENGAGEMENTS IN LONDON YOUNG VIC’S OLIVIER AWARD-WINNING PRODUCTION OF ARTHUR MILLER’S “A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE” Directed by IVO VAN HOVE STARRING MARK STRONG, NICOLA WALKER, PHOEBE FOX, EMUN ELLIOTT, MICHAEL GOULD IS COMING TO BROADWAY THIS FALL PREVIEWS BEGIN WEDNESDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 21 OPENING NIGHT IS THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 12 AT THE LYCEUM THEATRE Direct from two completely sold-out engagements in London, producers Scott Rudin and Lincoln Center Theater will bring the Young Vic’s critically-acclaimed production of Arthur Miller’s A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE to Broadway this fall. The production, which swept the 2015 Olivier Awards — winning for Best Revival, Best Director, and Best Actor (Mark Strong) —will begin previews Wednesday evening, October 21 and open on Thursday, November 12 at the Lyceum Theatre, 149 West 45 Street. -

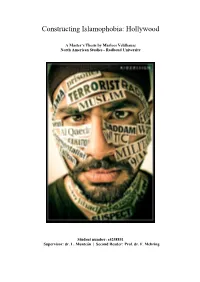

Constructing Islamophobia: Hollywood

Constructing Islamophobia: Hollywood A Master’s Thesis by Marloes Veldhausz North American Studies - Radboud University Student number: s4258851 Supervisor: dr. L. Munteán | Second Reader: Prof. dr. F. Mehring Veldhausz 4258851/2 Abstract Islam has become highly politicized post-9/11, the Islamophobia that has followed has been spread throughout the news media and Hollywood in particular. By using theories based on stereotypes, Othering, and Orientalism and a methodology based on film studies, in particular mise-en-scène, the way in which Islamophobia has been constructed in three case studies has been examined. These case studies are the following three Hollywood movies: The Hurt Locker, Zero Dark Thirty, and American Sniper. Derogatory rhetoric and mise-en-scène aspects proved to be shaping Islamophobia. The movies focus on events that happened post- 9/11 and the ideological markers that trigger Islamophobia in these movies are thus related to the opinions on Islam that have become widespread throughout Hollywood and the media since; examples being that Muslims are non-compatible with Western societies, savages, evil, and terrorists. Keywords: Islam, Muslim, Arab, Islamophobia, Religion, Mass Media, Movies, Hollywood, The Hurt Locker, Zero Dark Thirty, American Sniper, Mise-en-scène, Film Studies, American Studies. 2 Veldhausz 4258851/3 To my grandparents, I can never thank you enough for introducing me to Harry Potter and thus bringing magic into my life. 3 Veldhausz 4258851/4 Acknowledgements Thank you, first and foremost, to dr. László Munteán, for guiding me throughout the process of writing the largest piece of research I have ever written. I would not have been able to complete this daunting task without your help, ideas, patience, and guidance. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Logistics of perception 2.0: multiple screen aesthetics in Iraq War films Pisters, P. Publication date 2010 Document Version Final published version Published in Film-Philosophy Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Pisters, P. (2010). Logistics of perception 2.0: multiple screen aesthetics in Iraq War films. Film-Philosophy, 14(1), 232-252. http://www.film-philosophy.com/index.php/f- p/article/view/221/179 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:03 Oct 2021 Film-Philosophy 14.1 2010 Logistics of Perception 2.0: Multiple Screen Aesthetics in Iraq War Films Patricia Pisters University of Amsterdam Films about the Iraq War have appeared in remarkable quantities. -

European Journal of American Studies, 12-2 | 2017 “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Gl

European journal of American studies 12-2 | 2017 Summer 2017, including Special Issue: Popularizing Politics: The 2016 U.S. Presidential Election “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Global Frontiers of the Western Genre Lennart Soberon Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/12086 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.12086 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Lennart Soberon, ““The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Global Frontiers of the Western Genre”, European journal of American studies [Online], 12-2 | 2017, document 12, Online since 01 August 2017, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ ejas/12086 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.12086 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Gl... 1 “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Global Frontiers of the Western Genre Lennart Soberon 1 While recent years have seen no shortage of American action thrillers dealing with the War on Terror—Act of Valor (2012), Zero Dark Thirty (2012), and Lone Survivor (2013) to name just a few examples—no film has been met with such a great controversy as well as commercial success as American Sniper (2014). Directed by Clint Eastwood and based on the autobiography of the most lethal sniper in U.S. military history, American Sniper follows infamous Navy Seal Chris Kyle throughout his four tours of duty to Iraq.