Australian Stories of Social Enterprise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DEADLYS® FINALISTS ANNOUNCED – VOTING OPENS 18 July 2013 Embargoed 11Am, 18.7.2013

THE NATIONAL ABORIGINAL & TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER MUSIC, SPORT, ENTERTAINMENT & COMMUNITY AWARDS DEADLYS® FINALISTS ANNOUNCED – VOTING OPENS 18 July 2013 Embargoed 11am, 18.7.2013 BC TV’s gripping, award-winning drama Redfern in the NBA finals, Patrick Mills, are finalists in the Male Sportsperson Now is a multiple finalist across the acting and of the Year category, joining two-time world champion boxer Daniel television categories in the 2013 Deadly Awards, Geale, rugby union’s Kurtley Beale and soccer’s Jade North. with award-winning director Ivan Sen’s Mystery Across the arts, Australia’s best Indigenous dancers, artists and ARoad and Satellite Boy starring the iconic David Gulpilil. writers are well represented. Ali Cobby Eckermann, the SA writer These were some of the big names in television and film who brought us the beautiful story Ruby Moonlight in poetry, announced at the launch of the 2013 Deadlys® today, at SBS is a finalist with her haunting memoir Too Afraid to Cry, which headquarters in Sydney, joining plenty of talent, achievement tells her story as a Stolen Generations’ survivor. Pioneering and contribution across all the award categories. Indigenous award-winning writer Bruce Pascoe is also a finalist with his inspiring story for lower primary-school readers, Fog Male Artist of the Year, which recognises the achievement of a Dox – a story about courage, acceptance and respect. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander musicians, will be a difficult category for voters to decide on given Archie Roach, Dan Sultan, The Deadly Award categories of Health, Education, Employment, Troy Cassar-Daley, Gurrumul and Frank Yamma are nominated. -

Social Entrepreneurship in Far North Queensland: Public Forum

geralt | pixabay.com/photo - 550763/ Social Entrepreneurship has become a global phenomenon and is a major source of social change and social innovation. It is a significant part of the economies of many countries and forms 8.7% of the broader entrepreneurial activity in Australia. This Public Forum brings together all those with an interest in social enterprise including social entrepreneurs, non-governmental agencies, policy makers, academics, students and funders. The key focus of the Forum will be to explore the potential and to chart a new direction towards developing social entrepreneurship in Far North Queensland. Free event but please register at events.jcu.edu.au/SocialEntreForum Keynote speaker Cheryl Kernot plus short presentations by social entrepreneurs, and group work on building a social entrepreneurship network in FNQ Cheryl Kernot is one of the National Trust's 100 National Living Treasures. She was a member of the Australian Senate representing Queensland for the Australian Democrats from 1990 to 1997, and was the fifth leader of the Australian Democrats from 1993 to 1997. Recently, she worked in the UK as the program director for the Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurs at the Said Business School at Oxford University and later, as the director of learning at the School for Social Entrepreneurs in London. After six years in these roles in the UK, she moved back to Australia. Cheryl is currently the Social Business Fellow at the Centre for Social Impact. Her role at CSI involves providing thought leadership on social business, social enterprise and social procurement. She writes regularly on these topics, speaks at events throughout Australia and advises emerging talent and organizations. -

Roger-Bonastre-Sirerol-CANTANDO

+ PAPELES DEL FESTIVAL de música española DE CÁDIZ Revista internacional Nº 9 Año 2012 Música hispana y ritual CONSEJERÍA DE CULTURA Y DEPORTE Centro de Documentación Musical de Andalucía Depósito Legal: GR-487/95 I.S.S.N.: 1138-8579 Edita © JUNTA DE ANDALUCÍA. Consejería de Cultura y Deporte. Centro de Documentación Musical de Andalucía Carrera del Darro, 29 18002 Granada [email protected] www.juntadeandalucia.es/cultura/centrodocumentacionmusical Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/DocumentacionMusicalAndalucia Twitter: http://twitter.com/CDMAndalucia Música Oral del Sur + Papeles del Festival de música española de Cádiz es una revista internacional dedicada a la música de transmisión oral, desde el ámbito de la antropología cultural a la recuperación del Patrimonio Musical de Andalucía y a la nueva creación, con especial atención a las mujeres compositoras. Dirigida a musicólogos, investigadores sociales y culturales y en general al público con interés en estos temas. Presidente LUCIANO ALONSO ALONSO, Consejero de Cultura y Deporte de la Junta de Andalucía. Director REYNALDO FERNÁNDEZ MANZANO y MANUEL LORENTE RIVAS Presidente del Consejo Asesor JOSÉ ANTONIO GONZÁLEZ ALCANTUD (Universidad de Granada) Consejo Asesor MARINA ALONSO (Fonoteca del Museo Nacional de Antropología. INAH – Mexico DF) SERGIO BONANZINGA (Universidad de Palermo - Italia) FRANCISCO CANOVAS (Auditorio Nacional de España) EMILIO CASARES RODICIO (Dir. del Instituto Complutense de Ciencias Musicales) TERESA CATALÁN (Conservatorio Superior de Música -

Songs in the Key of Melbourne; Melbourne in the Key of Song

Songs in the key of Melbourne; Melbourne In the Key of Song. Research assignment SRA744 - Urban Patterns and Precedents Matt Novacevski, 2013 “Representations of a city and its life in the arts can be narrative ‘portraits’, local or ‘synoptic’ descriptions, ac- cording to Shapiro. Choosing a particular city—[...your A1 city ?...]— as the object of such representation, examine and discuss what can be learned about the nature of that city from any of those descriptions. Use specific examples for you inferences to give them credibility.” It has been claimed that Melbourne is the subject of popular song more than any Australian city (1). Since the 1970s, the city has been an incubator for the Australian music scene, growing some of Australia’s biggest artists and music industry players (2). In this context, it is natural that this music would that tell us much about the nature of Melbourne. Melbourne has been a muse to musicians and songwriters, which have in turn left to the city a series of cultural portraits in their songs that have not only described Melbourne; they have shaped its reality. Melbourne and its songwriters can be seen to have developed a symbiotic relationship where songwriters are inspired by the many faces of the city, while their songs are cultural documents that influence the way people view and interact with the city. As Keeling says, music acts “as a mirror to and for society, and it plays a very important role in shaping both our social identity and the identity of places” (3). While this project demonstrates the importance of popular music in reflecting and shaping the Melbourne’s sense of place, it does not seek to provide a comprehensive account of all this material - partly because songwriting focused on and inspired by Melbourne has been so prolific. -

NOTES for TEACHERS TELL ME WHY for YOUNG ADULTS By

NOTES FOR TEACHERS TELL ME WHY FOR YOUNG ADULTS by ARCHIE ROACH SYNOPSIS Tell Me Why for Young Adults is an abridged version of Archie Roach AM’s highly acclaimed adult memoir, Tell Me Why, the Story of My Life and My Music, first published in 2019. Intimate, moving and utterly compelling, Archie’s life story traces the enormous odds he overcomes and his experiences of family and community, love and heartbreak, survival and renewal – and the healing power of music. The book also contains a playlist for young people curated by Archie, and the lyrics of many of his songs – in themselves powerful historical testimonies. Through a series of conversations, facilitated online during COVID-19, Archie connected with Elders and young people, enabling them to record their thoughts, memories and song lyrics. Some of their powerful words are included in the book. To view the conversations and to access an extensive suite of lesson plans and videos, please visit the Archie Roach Stolen Generations Resources, freely available on ABC Education. Created using song, books and stories to promote critical conversations across the country, the Resources are the result of a unique collaboration between the Archie Roach Foundation and Culture is Life. The focus was Archie’s iconic single ‘Took the Children Away’ from his multi-award-winning 1990 debut album Charcoal Lane, celebrating its 30th anniversary this year. After the pandemic shut down what was to be his final Australian tour, Roach re-recorded the Songs of Charcoal Lane at his kitchen table, on his mother’s ancestral homelands, Gunditjmara country, in south-western Victoria. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-NINTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION TUESDAY, 2 FEBRUARY 2021 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable LINDA DESSAU, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable KEN LAY, AO, APM The ministry Premier ........................................................ The Hon. DM Andrews, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Education and Minister for Mental Health The Hon. JA Merlino, MP Attorney-General and Minister for Resources ........................ The Hon. J Symes, MLC Minister for Transport Infrastructure and Minister for the Suburban Rail Loop ........................................................ The Hon. JM Allan, MP Minister for Training and Skills, and Minister for Higher Education .... The Hon. GA Tierney, MLC Treasurer, Minister for Economic Development and Minister for Industrial Relations ........................................... The Hon. TH Pallas, MP Minister for Public Transport and Minister for Roads and Road Safety .. The Hon. BA Carroll, MP Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change, and Minister for Solar Homes ................................................. The Hon. L D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Child Protection and Minister for Disability, Ageing and Carers ....................................................... The Hon. LA Donnellan, MP Minister for Health, Minister for Ambulance Services and Minister for Equality .................................................... -

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Perspectives

NOVELS Baillie, Allan The First Voyage F BAI:A An adventure story set in our very distant past, 30,000 years ago, when the first tribes from Timor braved the ocean on primitive rafts to travel into the unknown, and reached the land mass of what is now Australia. Baillie, Allan Songman F BAI:A This story is set in northern Australia in 1720, before the time of Captain Cook. Yukuwa sets out across the sea to the islands of Indonesia. It is an adventure contrasting lifestyles and cultures, based on an episode of our history rarely explored in fiction. Birch, Tony, The White Girl F BIR:T Odette Brown has lived her whole life on the fringes of a small country town. After her daughter disappeared and left her with her granddaughter Sissy to raise on her own, Odette has managed to stay under the radar of the welfare authorities who are removing fair-skinned Aboriginal children from their families. When a new policeman arrives in town, determined to enforce the law, Odette must risk everything to save Sissy and protect everything she loves. Boyd, Jillian Bakir and Bi F BOY:J Bakir and Bi is based on a Torres Strait Islander creation story with illustrations by 18-year-old Tori-Jay Mordey. Bakir and Mar live on a remote island called Egur with their two young children. While fishing on the beach Bakir comes across a very special pelican named Bi. A famine occurs, and life on the island is no longer harmonious. Bunney, Ron The Hidden F BUN:R Thrown out of home by his penny-pinching stepmother, Matt flees Freemantle aboard a boat, only to be bullied and brutalised by the boson. -

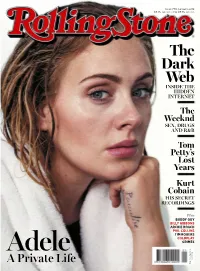

Rolling Stone | Rollingstoneaus.Com January, 2016

Issue 770 January 2016 $9.95 (GST INC) >> NZ $9.95 (GST INC) The Dark Web INSIDE THE HIDDEN INTERNET The Weeknd SEX, DRUGS AND R&B Tom Petty’s Lost Years Kurt Cobain HIS SECRET RECORDINGS Plus BUDDY GUY BILLY GIBBONS ARCHIE ROACH PHIL COLLINS TIM ROGERS COLDPLAY Adele GRIMES A Private Life 100007738 Print Post Approved Print Post More rooms. More music. More happy. 2 Room Starter Set - $529 $YDLODEOHDW-%+L)L+DUYH\1RUPDQ 6SHFLDOLVW+L)L6WRUHV Limited time offer. Save $69. 2σHUSHULRGDSSOLHV1RYWR'HF ELVIS PRESLEY JOE COCKER Elvis as you have never heard him before! The first comprehensive double album of Joe’s entire Featuring classic Elvis hits including musical history 36 unforgettable recordings, including ‘Burning Love’, Love Me Tender’, and ‘Fever’ ‘You Are So Beautiful’, ‘Many Rivers To Cross’, and (featuring Michael Buble). ‘You Can Leave Your Hat On’. ROGER WATERS BOB DYLAN The eponymous soundtrack to the globally acclaimed Latest volume in acclaimed Dylan Bootleg series feature filmCaptures Waters’ sold-out 2010-2013 premieres previously unreleased studio recordings. ‘The Wall Live’ tour, the first complete staging of the Includes never-before-heard songs, outtakes, rehearsal classic Pink Floyd concept album since 1990. tracks, and alternate versions, from the BRINGING IT ALL BACK HOME, HIGHWAY 61 REVISITED and BLONDE ON BLONDE Sessions. LEGENDS ALBUMS AC/DC DAVID GILMOUR ROCK OR BUST! Brand new solo album. New album featuring ‘Play Ball’, and ‘Rock Or Bust’. Features ‘Rattle That Lock’, A Boat Lies Waiting’, and ‘The Girl In The Yellow Dress’. JEFF LYNNE’S ELO BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN First album of all-new ELO music in over a decade! Contains 4 CDs, with a wealth of unreleased material, Features new songs including ‘When I Was A Boy’, and 4 hours of never-before-seen video on 3 DVDs ‘When The Night Comes’, and ‘ The Sun Will Includes studio outtakes; a two-DVD film of never- Shine on You’. -

Hansard 30 Oct 1997

30 Oct 1997 Vacancy in Senate of Commonwealth of Australia 4051 THURSDAY, 30 OCTOBER 1997 As this Parliament does not have a representative of the Australian Democrats, I move the motion nominating the authorised Australian Democrat nominee and the Leader At 8.45 a.m., of the Opposition seconds the motion. I am very happy to do so, as I am sure my Mr SPEAKER (Hon. N. J. Turner, Nicklin) colleague opposite is happy to second. took the chair. Despite the politics of Cheryl Kernot's precipitate resignation from the Parliament VACANCY IN SENATE OF COMMONWEALTH and the Australian Democrats, it is appropriate OF AUSTRALIA and correct that a spirit of bipartisanship is manifested today in choosing her successor. Nomination of Andrew John Julian Bartlett, vice Cheryl Kernot Today is also an historic occasion because it is the first time to my knowledge Mr SPEAKER: Order! The House has that the Queensland Parliament has fast- resolved to meet at 8.45 a.m. this day for the tracked the selection process by suspending purpose of the election of a senator. There Standing Orders so that the expressed wish of being a quorum present, the meeting is now the Queensland electorate is in no way constituted. Honourable members should note diminished. Honourable members will be that the provisions of Standing Orders and aware that the Government in the House of Rules shall apply to this meeting. I now call for Representatives and the Senate has granted nominations. I point out that every nomination a pair so that, until the Queensland Parliament must be accompanied by a declaration by the fills the vacancy, the relative voting strength of nominee of qualification and consent to be the parties in the Senate is not altered. -

The Many Faces of Political Eve: Representations of Queensland Women Parliamentarians in the Media

The Many Faces of Political Eve: Representations of Queensland Women Parliamentarians in the Media Julie Ustinoff 'Forget Policy — I've Got Great Legs!' That newspaper headline was one of the most interesting if not anomalous banners to appear during the 1998 federal election campaign. It was run in the Daily Telegraph1 as the header to an article about Pauline Hanson, who was busy campaigning for the Queensland seat of Blair in the state elections. As one might expect from the headline, the story dismissed any consideration of Hanson's political agenda in favour of blatant and highly sexualised comment about her very feminine physical attributes. Whilst this sort of media attention openly negated Hanson as a serious political force, it was indicative of the way the media had come to portray her since she arrived on the political scene two years earlier. Moreover, it was symptomatic of the media's widespread concern with portraying female politicians of all parties in accordance with worn-out assumptions and cliches, which rarely — if ever — were applied to their male counterparts. This paper is not intended as an analysis or discussion about the political ideologies or career of Pauline Hanson. It focuses instead on the media representations of Pauline Hanson as part of a wider argument about the problematic relationship that has developed between the Australian media and female politicians. It contends that the media treat all female politicians differently to the way they treat men, and furthermore that the difference serves to disadvantage women, often to the detriment of their professional and personal lives. -

Women in Music Mentor Program 2020 Advisory Committee

Women In Music Mentor Program 2020 Advisory Committee Ali Tomoana A proud Māori/Samoan woman and Mother, Ali is the Co-Founder/Director of Brisbane-based Indie Record Label and Artist Management agency, Soul Has No Tempo. With a joint passion for cultivating and supporting local music, Ali & her husband Gavin created SHNT as a one-stop-shop for emerging artists to perform, create and release music. Managing breakthrough Australian artist Jordan Rakei through his early development and reloca- tion to London, Ali now proudly represents Ladi6, Tiana Khasi and Ella Haber, along with Melbourne-based singer-songwriter, Laneous, and is inspired daily by the qualities that make each artist unique. As a label, SHNT dive deep into music that pushes the boundaries of Soul, while exploring new methods in which their artists can control their freedom of expression as creators. Anne Wiberg Anne established her own business as a freelance promoter, music programmer and event and project producer in late 2017. Recent clients have included AIR Awards (Australian Independent Records), State Government for the annual Ruby Awards, South Australia’s premier arts awards, Darwin Festival as Music Programmer, Adelaide Festival as Producer of “Picaresque” with Robyn Archer for the 2019 season, Insite Arts, Mercury Cinema, and Adelaide Fringe Festival as content producer in 2018 and Gala Director for the 2020 event. For the past twelve months, she has worked as a consultant for the Adelaide Botanic Gardens and State Herbarium to assist the organisation with developing a public arts program for winter months. As well as starting to promote her own live music events, she also produces programs and talent for private and corporate events. -

Ruby Hunter, 1955-2010 John Harding and Oliver Haag Ruby

Zeitschrift für Australienstudien / Australian Studies Journal ZfA 26/2012 Seite | 111 In Memory of a Deadly Voice: Ruby Hunter, 1955-2010 John Harding and Oliver Haag Ruby Hunter was more than a song writer: her songs are autobiographical, socio-critical and eminently historical, revolving around political issues, such as the Stolen Generations, Indigenous sovereignty and women’s issues. Her music, partly performed in collaboration with her life partner Archie Roach, is not merely entertainment and pleasure. Hunter’s songs are deeply personal. They reveal her own experiences of having been forcibly removed from her family and the path of becoming a devoted artist, activist and intellectual. Ruby’ Story tells of her own life as a member of the Stolen Generation—without bitterness or reproach. Let My Children Be is a powerful voice for diversity and plurality in Australian society. Ruby Hunter was born in South Australia in 1955 and died of a heart attack in February 2010. Despite her relatively short life, she became a songwriter of international recognition. Zeitschrift für Australienstudien honours Ruby Hunter’s life and work. It presents a poem by John Harding which captures Hunter’s road to becoming an artist and includes a selected discography of her songs. I raise my glass to Ruby by John Harding I remember the 80’s in suburban Fitzroy, my youth at that time meant my memory is clear. You could see the camaraderie that exuded silently from all the Kooris, a smile a kiss and a handshake our passports to each other. 112 | Seite Obituaries You could honestly smell the love and respect we had for one another.