Should Canada Consider Proportional Representation?" March 15, 2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..146 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 8.00)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 140 Ï NUMBER 098 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 38th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, May 13, 2005 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire´´ at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 5957 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, May 13, 2005 The House met at 10 a.m. Parliament on February 23, 2005, and Bill C-48, an act to authorize the Minister of Finance to make certain payments, shall be disposed of as follows: 1. Any division thereon requested before the expiry of the time for consideration of Government Orders on Thursday, May 19, 2005, shall be deferred to that time; Prayers 2. At the expiry of the time for consideration of Government Orders on Thursday, May 19, 2005, all questions necessary for the disposal of the second reading stage of (1) Bill C-43 and (2) Bill C-48 shall be put and decided forthwith and successively, Ï (1000) without further debate, amendment or deferral. [English] Ï (1010) MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE The Speaker: Does the hon. government House leader have the The Speaker: I have the honour to inform the House that a unanimous consent of the House for this motion? message has been received from the Senate informing this House Some hon. members: Agreed. that the Senate has passed certain bills, to which the concurrence of this House is desired. Some hon. members: No. Mr. Jay Hill (Prince George—Peace River, CPC): Mr. -

Wednesday, April 24, 1996

CANADA VOLUME 134 S NUMBER 032 S 2nd SESSION S 35th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, April 24, 1996 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) The House of Commons Debates are also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1883 HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, April 24, 1996 The House met at 2 p.m. [English] _______________ LIBERAL PARTY OF CANADA Prayers Mr. Ken Epp (Elk Island, Ref.): Mr. Speaker, voters need accurate information to make wise decisions at election time. With _______________ one vote they are asked to choose their member of Parliament, select the government for the term, indirectly choose the Prime The Speaker: As is our practice on Wednesdays, we will now Minister and give their approval to a complete all or nothing list of sing O Canada, which will be led by the hon. member for agenda items. Vancouver East. During an election campaign it is not acceptable to say that the [Editor’s Note: Whereupon members sang the national anthem.] GST will be axed with pledges to resign if it is not, to write in small print that it will be harmonized, but to keep it and hide it once the _____________________________________________ election has been won. It is not acceptable to promise more free votes if all this means is that the status quo of free votes on private members’ bills will be maintained. It is not acceptable to say that STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS MPs will be given more authority to represent their constituents if it means nothing and that MPs will still be whipped into submis- [English] sion by threats and actions of expulsion. -

Core 1..140 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 139 Ï NUMBER 006 Ï 3rd SESSION Ï 37th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Monday, February 9, 2004 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) Also available on the Parliament of Canada Web Site at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 285 HOUSE OF COMMONS Monday, February 9, 2004 The House met at 11 a.m. signals broadcast by satellite. They then sell this illegal equipment to consumers who are thus able to get satellite television free of charge. [English] Prayers I have heard some suggest that this is a victimless crime, that stealing from big, faceless companies is somehow much more GOVERNMENT ORDERS acceptable in our society than stealing from our neighbours. Ï (1100) Let me assure the House that this is not a victimless crime. The [Translation] theft of the satellite signals denies legitimate Canadian broadcasters, content producers and programmers millions of dollars a year. It robs RADIOCOMMUNICATION ACT money from an industry that supports thousands of jobs. It is not Bill C-2—On the Order: Government Orders only morally and ethically wrong, it is illegal. February 5, 2004—The Minister of Industry—Second reading and reference to the Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology of Bill C-2, an act to amend the Radiocommunication Act. Such actions contravene the Radiocommunication Act. In fact, a Supreme Court decision in April 2002 determined that the Hon. Lucienne Robillard (Minister of Industry and Minister unauthorized recording of any encrypted subscription programming responsible for the Economic Development Agency of Canada signal is illegal, no matter where it originates. -

Wednesday, May 8, 1996

CANADA VOLUME 134 S NUMBER 042 S 2nd SESSION S 35th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, May 8, 1996 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) OFFICIAL REPORT At page 2437 of Hansard Tuesday, May 7, 1996, under the heading ``Report of Auditor General'', the last paragraph should have started with Hon. Jane Stewart (Minister of National Revenue, Lib.): The House of Commons Debates are also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 2471 HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, May 8, 1996 The House met at 2 p.m. [Translation] _______________ COAST GUARD Prayers Mrs. Christiane Gagnon (Québec, BQ): Mr. Speaker, another _______________ voice has been added to the general vehement objections to the Coast Guard fees the government is preparing to ram through. The Acting Speaker (Mr. Kilger): As is our practice on Wednesdays, we will now sing O Canada, which will be led by the The Quebec urban community, which is directly affected, on hon. member for for Victoria—Haliburton. April 23 unanimously adopted a resolution demanding that the Department of Fisheries and Oceans reverse its decision and carry [Editor’s Note: Whereupon members sang the national anthem.] out an in depth assessment of the economic impact of the various _____________________________________________ options. I am asking the government to halt this direct assault against the STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS Quebec economy. I am asking the government to listen to the taxpayers, the municipal authorities and the economic stakehold- [English] ers. Perhaps an equitable solution can then be found. -

Top 41 Ridings with a Population of 40 Per Cent Or More Immigrants

4 THE HILL TIMES, MONDAY, OCTOBER 3, 2011 NEWS: ETHNIC RIDINGS Feds poised to bring in House seats bill, to increase urban, suburban ethnic ridings Under the old bill, Ontario was expected to receive 18 seats, Alberta five and British Columbia seven. Continued from Page 1 Top 41 Ridings With A Population Of 40 Per Cent Or More Immigrants Riding Per cent of Current MP 2011 election results Second Place 2011 election Incumbent results from Immigrants in riding 2008 election 1. Scarborough-Rouge River, Ont. 67.7% NDP MP Rathika Sitsabaiesan 40.6% Conservative Marlene Gallyot, 29.9% Liberal Derek Lee, 58.8% 2. Scarborough-Agincourt, Ont. 67.7% Liberal Jim Karygiannis 45.4% Conservative Harry Tsai, 34.2% Liberal Jim Karygiannis, 56.6% 3. Markham-Unionville, Ont. 62% Liberal John McCallum 38.95% Conservative Bob Saroya, 35.6% Liberal John McCallum, 55% 4. York West, Ont. 61.4% Liberal Judy Sgro 47% NDP Giulio Manfrini, 27.9% Liberal Judy Sgro, 59.4% 5. Don Valley East, Ont. 61.3% Conservative Joe Daniel 36.8% Liberal Yasmin Ratansi, 34.6% Liberal Yasmin Ratansi, 48% 6. Mississauga East-Cooksville, Ont. 61.1% Conservative Wladyslaw Lizon 39.97% Liberal Peter Fonseca, 38.5% Liberal Albina Guarnieri, 50.2% 7. Richmond, B.C. 61.1% Conservative Alice Wong 58.3% Liberal Joe Peschisolido, 18.7% Conservative Alice Wong, 49.8% 8. Vancouver South, B.C. 60.3% Conservative Wai Young 43.3% Liberal Ujjal Dosanjh, 34.7% Liberal Ujjal Dosanjh, 38.5% 9 Willowdale, Ont. 60.2% Conservative Chungsen Leung 41.7% Liberal Martha Hall Findlay, 39.95% Liberal Martha Hall Findlay, 48.7% 10. -

Core 1..176 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 7.50)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 138 Ï NUMBER 072 Ï 2nd SESSION Ï 37th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Tuesday, March 18, 2003 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire´´ at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 4325 HOUSE OF COMMONS Tuesday, March 18, 2003 The House met at 10 a.m. [English] PETITIONS Prayers STEM CELL RESEARCH Mr. Paul Szabo (Mississauga South, Lib.): Madam Speaker, I ROUTINE PROCEEDINGS am pleased to present a petition on behalf of a number of Canadians, including from my own riding of Mississauga South, on the subject Ï (1005) matter of stem cells. [English] ORDER IN COUNCIL APPOINTMENTS The petitioners draw to the attention of the House that thousands of Canadians suffer from very debilitating diseases which need to be Mr. Geoff Regan (Parliamentary Secretary to the Leader of addressed and that Canadians support ethical stem cell research the Government in the House of Commons, Lib.): Madam which has already shown encouraging potential to prevent and to Speaker, it is my honour to table, in both official languages, a cure many of the illness and diseases that they hold. number of Order in Council appointments made recently by the government. They also point out that non-embryonic stem cells, which are also *** known as adult stem cells, have shown significant progress without GOVERNMENT RESPONSE TO PETITIONS the immune rejection or ethical problems associated with embryonic stem cells. Mr. Geoff Regan (Parliamentary Secretary to the Leader of the Government in the House of Commons, Lib.): Madam Speaker, pursuant to Standing Order 36(8) I have the honour to table, The petitioners therefore call upon Parliament to pursue legislative in both official languages, the government's response to 10 petitions. -

Friday, March 5, 1999

CANADA VOLUME 135 S NUMBER 190 S 1st SESSION S 36th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, March 5, 1999 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire'' at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 12481 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, March 5, 1999 The House met at 10 a.m. As I said, it is important from my point of view to put into context the importance of Bill C-49 and the contribution that it will _______________ make to ensuring a commitment which this government has to work with first nations to build self-reliance and to provide first Prayers nations the opportunity to have the social and economic control _______________ that they need to have to better their lives within the community and the lives of their community members. GOVERNMENT ORDERS Second, if I have the time I would like to explore some of the issues that have been raised in the last few days with respect to Bill D (1000 ) C-49. I anticipate that I will be able to do that. If not, I know my parliamentary secretary will speak to some of those issues. [English] First and foremost, let us consider the context in which Bill C-49 FIRST NATIONS LAND MANAGEMENT ACT finds itself. In this regard I would like to remind the House about Hon. Jane Stewart (Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern the fact that the primary relationship that I as minister of Indian Development, Lib.) moved that Bill C-49, an act providing for the affairs and the Government of Canada has with first nations is ratification and the bringing into effect of the framework agree- through the Indian Act. -

Colombian Refugee Migrant Experiences of Health And

COLOMBIAN REFUGEE MIGRANT EXPERIENCES OF HEALTH SERVICES IN OTTAWA, CANADA COLOMBIAN REFUGEE MIGRANT EXPERIENCES OF HEALTH AND SOCIAL SERVICES IN OTTAWA, CANADA: NAVIGATING LANDSCAPES OF LANGUAGE AND MEMORY By: ANDREW GALLEY, H.B.Sc, M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Andrew Galley, August 2011 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY McMaster University (Anthropology) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Colombian Refugee Migrant Experiences of Health and Social Services in Ottawa, Canada: Navigating Landscapes of Language and Memory. AUTHOR: Andrew Galley, H.B.Sc (University of Toronto), M.A. (University of Toronto). SUPERVISOR: Dr. Ellen Badone NUMBER OF PAGES: vii + xx (xx total) ii Abstract This thesis presents a multi-level and mixed-method analysis of the health-care experiences of predominantly Colombian migrants living in Ottawa, Canada. It incorporates survey, interview, archival and participant-observation data to answer a series of linked questions regarding health and migration under contemporary Canadian liberal governance. Specifically, the thesis elucidates connections between bodily experiences of illness and healing, linguistic and cultural fractures within communities, and the legal positioning of refugee migrants in Canadian law. In doing so it follows the "three bodies" model of medical anthropology proposed by Lock and Scheper-Hughes. The first three chapters of the thesis provide multiple layers of context for the fourth chapter, which contains the bulk of the primary ethnographic evidence. The first chapter analyzes the positioning of the refugee subject in Canadian legislative and policy discourse, highlighting the phenomenon of the immigrant as subaltern nationalist "hero" who is denied a full voice in public affairs but whose passive qualities are considered essential for the cultural reproduction of the nation. -

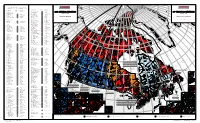

Map of Canada, the 38Th Parliament

www.elections.ca T N E NUMBER OF DISTRIBUTION OF VALID M VOTES CAST (%) A PERCENTAGE DISTRIBUTION OF VALID VOTES CAST AND NUMBER OF CANDIDATES ELECTED: JUNE 28, 2004 A ELECTORS VOTES CAST I PARTY L CANDIDATE ELECTED ON THE Political Affiliation R THE HOUSE OF COMMONS ELECTORAL DISTRICT R ELECTED A LISTS C P h t VALID REJECTED T S The Speaker – The Honourable Peter Milliken 7 a 3 I i MAJORITY (%) b NEWFOUNDLAND PRINCE EDWARD C D um NOVA SCOTIA NEW BRUNSWICK QUEBEC ONTARIO ol CANADA EC 62353 EC C AND LABRADOR ISLAND The Deputy Speaker – Chuck Strahl O N C t C Aler E A !( A L 48.0% 52.5% 39.7% 44.6% 33.9% 44.7% The Prime Minister – The Right Honourable Paul Martin, PC 35045 Markham—Unionville Hon. John McCallum, PC x 82,256 45,908 239 66.3 22.5 8.7 2.5 43.8 N 4.6% S 35046 Middlesex—Kent—Lambton Rose-Marie Ur 39.7 39.4 15.1 5.8 0.3 I 36.7% x 78,129 48,965 245 0.1% 0.3% The Leader of the Opposition – The Honourable Stephen Harper, PC 0.7% 0.7% Ph 0.6% 1.3% 35047 Mississauga—Brampton South Navdeep Bains 81,037 43,307 321 57.2 24.1 14.8 3.9 33.1 H illips 3.3% 3.4% 3.2% In 15.7% 1.6% 4.2% Hon. Albina Guarnieri, PC 56.7 26.0 11.7 5.6 30.7 T 18.1% 4.4% 35048 Mississauga East—Cooksville x 75,883 39,566 221 E 1.3% 17.5% 12.5% 28.4% 8.8% 20.6% 48.9% 35049 Mississauga—Erindale Carolyn Parrish x 86,640 51,950 269 54.4 32.0 9.8 3.8 22.4 B 4.3% 32.3% 30.7% 28.0% 31.1% A 31.5% Z THE 38th FEDERAL ELECTION, JUNE 28, 2004: 35050 Mississauga South Paul John Mark Szabo x 75,866 47,665 183 51.7 33.6 10.5 4.2 18.0 I 12.4% NORTHWEST N D L MANITOBA SASKATCHEWAN ALBERTA BRITISH COLUMBIA YUKON NUNAVUT Wajid Khan 35051 Mississauga—Streetsville 78,265 45,029 260 50.6 31.7 9.5 8.2 18.8 E a TERRITORIES n 29.6% N CANDIDATES ELECTED AND DISTRIBUTION OF VOTES CAST s 35052 Nepean—Carleton Pierre Poilievre 40.1 45.7 9.1 5.2 5.6 e 9.5% 45.7% 51.3% 89,044 66,623 225 N l n 33.2% 39.4% e CANADA S A o d 27.2% E P n un y F 23.4% d el 35053 Newmarket—Aurora Belinda Stronach 77,203 51,435 269 41.1 42.4 9.9 6.6 1.3 E e n Gre 22.0% 26.6% 28.6% a L a U h AXEL r 23.5% Q y C 35054 Niagara Falls Hon. -

Fixing Canadian Democracy

About the Fraser Institute The Fraser Institute is an independent Canadian economic and social research and educational organization. It has as its objective the redirection of public at- tention to the role of competitive markets in providing for the well-being of Ca- nadians. Where markets work, the Institute’s interest lies in trying to discover prospects for improvement. Where markets do not work, its interest lies in find- ing the reasons. Where competitive markets have been replaced by government control, the interest of the Institute lies in documenting objectively the nature of the improvement or deterioration resulting from government intervention. The Fraser Institute is a national, federally-chartered, non-profit organization financed by the sale of its publications and the tax-deductible contributions of its members, foundations, and other supporters; it receives no government fund- ing. Editorial Advisory Board Prof. Armen Alchian Prof. J.M. Buchanan Prof. Jean-Pierre Centi Prof. Herbert G. Grubel Prof. Michael Parkin Prof. Friedrich Schneider Prof. L.B. Smith Sir Alan Walters Prof. Edwin G. West Senior Fellows Murray Allen, MD Prof. Eugene Beaulieu Dr. Paul Brantingham Prof. Barry Cooper Prof. Steve Easton Prof. Herb Emery Prof. Tom Flanagan Gordon Gibson Dr. Herbert Grubel Prof. Ron Kneebone Prof. Rainer Knopff Dr. Owen Lippert Prof. Ken McKenzie Prof. Jean-Luc Migue Prof. Lydia Miljan Prof. Filip Palda Prof. Chris Sarlo Administration Executive Director, Michael Walker Director, Finance and Administration, Michael Hopkins Director, Alberta Policy Research Centre, Barry Cooper Director, Communications, Suzanne Walters Director, Development, Sherry Stein Director, Education Programs, Annabel Addington Director, Publication Production, J. -

Results Map (PDF Format)

2 5 3 2 a CANDIDATES ELECTED / CANDIDATS ÉLUS Se 6 ln ln A co co C R Lin in L E ELECTORAL DISTRICT PARTY ELECTED CANDIDATE ELECTED de ELECTORAL DISTRICT PARTY ELECTED CANDIDATE ELECTED C er O T S M CIRCONSCRIPTION PARTI ÉLU CANDIDAT ÉLU C I bia C D um CIRCONSCRIPTION PARTI ÉLU CANDIDAT ÉLU É ol N C A O C t C A H Aler 35050 Mississauga South / Mississauga-Sud Paul John Mark Szabo N E (! e A N L T 35051 Mississauga--Streetsville Wajid Khan A S E 38th GENERAL ELECTION R B 38 ÉLECTION GÉNÉRALE C I NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR 35052 Nepean--Carleton Pierre Poilievre T I A Q S Phi 35053 Newmarket--Aurora Belinda Stronach U H I llips TERRE-NEUVE-ET-LABRADOR June 28, 2004 E L In 28 juin, 2004 T É 35054 Niagara Falls Hon. / L'hon. Rob Nicholson E - 10001 Avalon Hon. / L'hon. R. John Efford B E 35055 Niagara West--Glanbrook Dean Allison A N 10002 Bonavista--Exploits Scott Simms I Z Niagara-Ouest--Glanbrook E I 10003 Humber--St. Barbe--Baie Verte Hon. / L'hon. Gerry Byrne L R N D 35056 Nickel Belt Raymond Bonin a E A n 10004 Labrador Lawrence David O'Brien L N s 35057 Nipissing--Timiskaming Anthony Rota e N E l n e S A o d E 10005 Random--Burin--St. George's Bill Matthews E n u F D n P y d el 35058 Northumberland--Quinte West Paul Macklin n Gre E e t s a L S i a U R h 10006 St. -

Hansard 33 1..168

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 137 Ï NUMBER 088 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 37th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, September 28, 2001 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire´´ at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 5703 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, September 28, 2001 The House met at 10 a.m. been one of longstanding co-operation, trust and mutual benefit. Formal trade relations between our two countries date back more Prayers than 50 years to a bilateral commercial agreement concluded in 1950. Since then our relationship has developed steadily. A free trade agreement will only make it stronger. GOVERNMENT ORDERS Both countries' citizens will be able to share in the prosperity that freer trade creates. Already our bilateral trade with Costa Rica has Ï (1000) seen an average annual growth of over 6% in the last five years with [English] a 7% increase in exports and a 5% increase in imports. The FTA will accelerate this growth. CANADA-COSTA RICA FREE TRADE AGREEMENT IMPLEMENTATION ACT Although our bilateral trading relationship is small, approximately Hon. Paul Martin (for the Minister for International Trade) $270 million, this number is rising rapidly. Indeed, there was a 25% moved that Bill C-32, an act to implement the Free Trade Agreement jump in our exports in the year 2000. It is also worth mentioning that between the Government of Canada and the Government of the we have invested about $500 million in Costa Rica.