Vowel Interactión in Bizcayan Basque

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Incertidumbres Asistenciales. De Manicomio a Seminario De Derio

NORTE DE SALUD MENTAL nº 29 • 2007 • PAG 124–128 HISTORIA Incertidumbres asistenciales. De Manicomio a Seminario de Derio Iñaki Markez CSM de Basauri En la década de los años 20, ante el aban- do en 1900 y también con cierta escasez de dono y deterioro de la organización psiquiátri- medios y de personal, tuvo como primer ca por parte del gobierno de Primo de Rivera, Director a López Albo, neuropsiquiatra forma- los psiquiatras comprometidos intentaron do en Alemania. El Dr.Wenceslao López Albo3 reformas en los ámbitos locales y en institu- fue un destacado neuropsiquiatra de la época ciones, privadas casi siempre, desplazando su siendo notorio por los proyectos que realizó. acción pública hacia las asociaciones profesio- Mencionaré aquí dos de ellos, en la Casa de nales1.Así ocurrió en la asamblea constituyen- Salud Valdecilla en Santander y el proyecto de te de la Asociación Española de Neuropsiquia- gran manicomio en Vizcaya. tras celebrada a finales de 1924, en un ambien- te crítico y de protesta, con la presencia de un En 1928 fue Jefe del Pabellón de Mentales y buen puñado de directores de manicomios organizador de la Casa de Salud de Valdecilla públicos y privados, algunos de ellos psiquia- durante dos años, hasta que dimitió al impo- tras de prestigio y después en la asamblea de nerle el Patronato la presencia de las Hijas de la AEN de junio de 1926 donde, además de la Caridad con cometidos inapropiados y con- aprobarse la constitución de la Liga Española trarias a sus iniciativas de que el cuidado de los de Higiene Mental; su tercera ponencia versa- pacientes lo realizaran enfermeras seglares. -

Equipo Crónica

Equipo Crónica Tomàs Llorens 1 This text is published under an international Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs Creative Commons licence (BY-NC-ND), version 4.0. It may therefore be circulated, copied and reproduced (with no alteration to the contents), but for educational and research purposes only and always citing its author and provenance. It may not be used commercially. View the terms and conditions of this licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-ncnd/4.0/legalcode Using and copying images are prohibited unless expressly authorised by the owners of the photographs and/or copyright of the works. © of the texts: Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao © Equipo Crónica (Manuel Valdés), VEGAP, Bilbao, 2015 Photography credits © Archivo Fotográfico Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Alicante, MACA: fig. 9 © Archivo Fotográfico Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía: figs. 11, 12 © Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa-Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao: figs. 15, 20 © Colección Arango: fig. 18 © Colección Guillermo Caballero de Luján: figs. 4, 7, 10, 16 © Fundación “la Caixa”. Gasull fotografía: fig. 8 © Patrimonio histórico-artístico del Senado: fig. 19 © Stiftung Museum Kunstpalast - ARTOTHEK: fig. 14 Original text published in the catalogue Equipo Crónica held at the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum (10 February to 18 May 2015). Sponsored by: 2 1 Estampa Popular de Valencia and the beginnings of Equipo Crónica Founded in 1964, Equipo Crónica and Estampa Popular de Valencia presented themselves to the public as two branches of a single project. Essentially, however, they were two different, independent ones and either could have appeared and evolved without the other. -

Erandio Bilbao

MAPAS ESTRATEGICOS DE RUIDO DE LA RED FORAL DE CARRETERAS DE BIZKAIA Carretera BI-604 1/5 DIRECTIVA 2002/49/CE - FASE II BI-604 – UME 2 • Discurre en dirección norte-sur a lo largo de 4,8 km (PK.2+700 a PK. 7+500). • Implica a los municipios de: Erandio (24.294 hab.) y Bilbao (353.187 hab.). • En el municipio de Erandio se identifican, bajo la influencia de la carretera BI-604, únicamente dos zonas de uso residencial colectivo y unitario, siendo el resto del entorno de su trazado de uso industrial o sin calificación. En el municipio de Bilbao, la carretera BI-604 discurre próxima a dos zonas de especial sensibilidad (colegios), quedando soterrada en el entorno de las zonas residenciales. Municipios Implicados y Distribución de Usos Acústicos ERANDIO BILBAO HERRI LAN ETA GARRAIO SAILA DEPARTAMENTO DE OBRAS PUBLICAS Y TRANSPORTE MAPAS ESTRATEGICOS DE RUIDO DE LA RED FORAL DE CARRETERAS DE BIZKAIA Carretera BI-604 2/5 DIRECTIVA 2002/49/CE - FASE II DATOS DE TRAFICO. Año 2010 Nombre Longitud (km) PK_Inicio PK_Fin Codigo %Pesados IMD IMHL_Dia IMHL_Tarde IMHL_Noche V_Max Le10mdia Le10mtarde Le10mnoche Le10mden BI-604 0,1100 2,007 2,008 05738 0,0 9426 538 550 95 60 64,6 64,7 57,1 66,7 BI-604 0,1600 2,007 2,009 05738 0,0 9426 538 550 95 60 64,6 64,7 57,1 66,7 BI-604 0,0550 2,008 2,009 09151 0,0 9426 538 550 95 60 64,6 64,7 57,1 66,7 BI-604 0,4100 2,009 3,004 05741 0,0 9426 538 550 95 40 61,7 61,8 54,2 63,8 BI-604 0,4100 2,009 3,004 05754 0,0 9426 538 550 95 40 61,7 61,8 54,2 63,8 BI-604 0,0900 3,004 3,005 05742 0,0 9426 538 550 95 40 61,7 61,8 -

Paradas Autobús Sábados Winter Program 21-22 Bus Stops Saturday Winter Program 21-22

Paradas autobús Sábados Winter Program 21-22 Bus stops Saturday Winter Program 21-22 GETXO / LEIOA BILBAO BARRIKA / BERANGO Algorta Antigua Gasolinera Arenal San Nicolás GORLIZ / PLENTZIA Algorta Metro / Telepizza Arenal Soportales Sendeja Ambulatorio Las Arenas Alda. San Mames, 8 SOPELANA / URDULIZ Antiguo Golf Banco Alda. Urkijo, 68 Barrika Asilo P. Bus Estanco Guipuzcoano C/ Kristo, 1 Barrika Bar Cantábrico P Bus Artaza Cafetería Québec D. Bosco Biribilgunea / Berango Jesús Mª Leizaola, 18 Artaza Tximeleta Sarrikoalde P Bus Berango Moreaga Avenida del Angel Mª Diaz de Haro, 57 Berango Escuelas Ayuntamiento Getxo Autonomía C.P. Félix Serrano Berango Simón Otxandategi Fadura Iparraguirre P. Bus El Corte Gorliz Sanatorio Pequeño Gasolinera Neguri Inglés Gorliz Caja Laboral Gimnasio San Martín / Super Lehendakari Aguirre Bidarte Larrabasterra C/ Iberre BM Miribilla Av. Askatasuna Meñakoz* Ikastola Geroa en frente Plaza Circular Lateral BBVA Plentzia Cruce Gandias Instituto Aiboa Plaza Museo Plentzia Mungia bidea 14 P. Bus Instituto Romo Plaza San Pedro Plentzia Rotonda Charter Jolaseta Plentzia Puerto La Venta GALDAKAO / Sopelana Bar Urbaso Las Ardillas Sopelana Iglesia Leioa Centro Cívico TXORIERRI Urduliz Cuatro Caminos Leioa Mendibile Avda. Zumalakarregui P. bus Urduliz P. Bus Jubilados Neguri Gasolinera / Regollos Panera Basauri Rotonda Matxitxako Los Puentes Begoña Hotel Holiday Inn MARGEN IZQUIERDA Oicosa P. Bus Barakaldo P. Bus Getxo Peña Sta. Marina Rotonda Begoña Pastelería Artagan Cruce Asua Dirección La Cabieces P. Bus Puente -

Portada Del Catálogo

RUMBO AL FUTURO El Puerto de Bilbao avanza en todos los sentidos. En capacidad logística, en nuevas infraestructuras y servicios, en innovación. Además de su privilegiada situación geográfi ca, ofrece unas instalaciones modernas y funcionales con una gran oferta de servicios marítimos abiertos a todos los mercados interna- cionales. Dispone de unas magnífi cas conexiones terrestres y ferroviarias que facilitan su potencial logístico, su intermodalidad. Desde hace más de 700 años, seguimos una línea de desarrollo constante para adelantarnos a las necesidades de nuestros usuarios. Los últimos 20 años los hemos dedicado a prepararnos para el futuro, realizando el proyecto de ampliación y mejora más importante de nuestra larga historia. Un proyecto que nos está convirtiendo en uno de los grandes puertos de referencia europeos. 2 ÍNDICE CENTRALIDAD INTERMODALIDAD DESARROLLO ATLÁNTICA SOSTENIBLE Página 04 Página 06 Página 10 OPERACIONES Y TERMINALES TERMINALES TERMINALES SERVICIOS SERVICIOS INDUSTRIALES COMERCIALES PASAJEROS COMERCIALES COMERCIALES Página 12 Página 14 Página 18 Página 28 Página 30 INDUSTRIAS INVERSIONES MERCADOS LÍNEAS MARÍTIMAS PLANO EN LA RÍA Y ASTILLEROS DIRECTAS PUERTO DE BILBAO SERVICIOS FEEDER EMPRESAS PORTUARIAS Página 36 Página 38 Página 42 Página 43 Página 54 3 BILBAO CENTRALIDAD ATLÁNTICA SITUACIÓN 4 DISTANCIAS ENTRE EL PUERTO DE BILBAO Y LOS SIGUIENTES PUERTOS DEL MUNDO Algeciras 867 millas Amberes 787 millas CENTRALIDAD Amsterdam 800 millas Bremerhaven 1.015 millas ATLÁNTICA Bristol 555 millas Buenos Aires 5.900 millas Burdeos 230 millas Dover 620 millas En el centro del Golfo de Bizkaia, equidistante Dublín 625 millas Emden 936 millas de Brest y Finesterre, el Puerto de Bilbao es una Estambul 2.640 millas Felixstowe 702 millas centralidad del Atlántico Europeo. -

Visit Oma's Forest, Santimamiñe's Cave, Bermeo, Mundaka and Gernika!

www.bilbaoakelarrehostel.com Visit Oma’s Forest, Santimamiñe’s cave, Bermeo, Mundaka and Gernika! All day trip Bilbao Akelarre Hostel c/ Morgan 4-6, 48014 Bilbao (Bizkaia) - Teléfono: (+34) 94 405 77 13 - [email protected] - www.bilbaoakelarrehostel.com www.bilbaoakelarrehostel.com - Leaving Bilbao Akelarre Hostel • Arriving to the “enchanted” forest of Oma Forest of Oma Located at 8 kilometers of Guernika and right in the middle of the Uradaibai biosphere reserve , The Oma forest offers to its visitors an image between art and mystery thanks to the piece of art of Agustín Ibarrola . 20 years ago, this Basque artist had the idea of giving life to the trees by painting them. That way, in a narrow and large valley, away from the civilisation and its noise, you can find a mixture of colours, figures and symbols that can make you feel all sorts of different sensations. Without any established rout, the visitor himself will have to find out their own vision of the forest. Bilbao Akelarre Hostel c/ Morgan 4-6, 48014 Bilbao (Bizkaia) - Teléfono: (+34) 94 405 77 13 - [email protected] - www.bilbaoakelarrehostel.com www.bilbaoakelarrehostel.com Bilbao Akelarre Hostel c/ Morgan 4-6, 48014 Bilbao (Bizkaia) - Teléfono: (+34) 94 405 77 13 - [email protected] - www.bilbaoakelarrehostel.com www.bilbaoakelarrehostel.com - Leaving Oma’s Forest • Arriving at Santimamiñe’s cave Santimamiñe’s Cave Located in the Biscay town of Kortezubi and figuring in the list of the Human Patrimony, Santimamiñe’s Cave represents one of the principle prehistorically site of Biscay. They have found in it remains and cave paintings who age back from the Palaeolithic Superior in the period of “Magdaleniense”. -

Bombing of Gernika

BIBLIOTECA DE The Bombing CULTURA VASCA of Gernika The episode of Guernica, with all that it The Bombing ... represents both in the military and the G) :c moral order, seems destined to pass 0 of Gernika into History as a symbol. A symbol of >< many things, but chiefly of that Xabier lruio capacity for falsehood possessed by the new Machiavellism which threatens destruction to all the ethical hypotheses of civilization. A clear example of the ..e use which can be made of untruth to ·-...c: degrade the minds of those whom one G) wishes to convince. c., '+- 0 (Foreign Wings over the Basque Country, 1937) C> C: ISBN 978-0-9967810-7-7 :c 90000 E 0 co G) .c 9 780996 781077 t- EDITORIALVASCA EKIN ARGITALETXEA Aberri Bilduma Collection, 11 Ekin Aberri Bilduma Collection, 11 Xabier Irujo The Bombing of Gernika Ekin Buenos Aires 2021 Aberri Bilduma Collection, 11 Editorial Vasca Ekin Argitaletxea Lizarrenea C./ México 1880 Buenos Aires, CP. 1200 Argentina Web: http://editorialvascaekin- ekinargitaletxea.blogspot.com Copyright © 2021 Ekin All rights reserved First edition. First print Printed in America Cover design © 2021 JSM ISBN first edition: 978-0-9967810-7-7 Table of Contents Bombardment. Description and types 9 Prehistory of terror bombing 13 Coup d'etat: Mussolini, Hitler, and Franco 17 Non-Intervention Committee 21 The Basque Country in 1936 27 The Basque front in the spring of 1937 31 Everyday routine: “Clear day means bombs” 33 Slow advance toward Bilbao 37 “Target Gernika” 41 Seven main reasons for choosing Gernika as a target 47 The alarm systems and the antiaircraft shelters 51 Typology and number of airplanes and bombs 55 Strategy of the attack 59 Excerpts from personal testimonies 71 Material destruction and death toll 85 The news 101 The lie 125 Denial and reductionism 131 Reconstruction 133 Bibliography 137 I can’t -it is impossible for me to give any picture of that indescribable tragedy. -

A Monthly E-Newsletter for the Latest in Cultural Management and Policy ISSUE N° 114

news A monthly e-newsletter for the latest in cultural management and policy ISSUE N° 114 DIGEST VERSION FOR OUR FOLLOWERS Issue N°104 / news from encatc / Page 1 CONTENTS NOTE FROM THE Issue N°114 NOTE FROM THE EDITOR EDITOR 2 Dear colleagues, Welcome to the new re-vamped online ENCATC resources to make it ENCATC NEWS 3 version of our monthly ENCATC easier to access direct sources and newsletter! material for your work! Finally, for those who liked the PDF just as it was, These last two months we took the UPCOMING you can still find all the information time to have a critical look at this very 10 you trust from ENCATC and can print EVENTS product we have been producing for this publication to take with you! you for over 20 years as well as to CALLS & ask the opinions of members, key The new format of the ENCATC stakeholders, and loyal readers in newsletter will also offer more space OPPORTUNITIES 13 order to find the new way to adapt this for contributions from our members information tool to reading practices and stakeholders. In this issue you will EUROPEAN YEAR and the digital environment. enjoy articles written by our members Lidia Varbanova, Claire Giraud-Labalte OF CULTURAL 14 So what is the next stage for ENCATC and Savina Tarsitano and from the HERITAGE 2018 News? Many said they were plagued network Future for Religious Heritage. by information overload and felt pressure to have updates quickly and Finally, to mark the European Year of ENCATC IN only a click away. -

Comparing the Basque Diaspora

COMPARING THE BASQUE DIASPORA: Ethnonationalism, transnationalism and identity maintenance in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Peru, the United States of America, and Uruguay by Gloria Pilar Totoricagiiena Thesis submitted in partial requirement for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2000 1 UMI Number: U145019 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U145019 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Theses, F 7877 7S/^S| Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully acknowledge the supervision of Professor Brendan O’Leary, whose expertise in ethnonationalism attracted me to the LSE and whose careful comments guided me through the writing of this thesis; advising by Dr. Erik Ringmar at the LSE, and my indebtedness to mentor, Professor Gregory A. Raymond, specialist in international relations and conflict resolution at Boise State University, and his nearly twenty years of inspiration and faith in my academic abilities. Fellowships from the American Association of University Women, Euskal Fundazioa, and Eusko Jaurlaritza contributed to the financial requirements of this international travel. -

The Basque Refugee Children of the Spanish Civil War in the Uk 177

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF LAW, ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES THE BASQUE REFUGEE CHILDREN OF THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR IN THE UK: MEMORY AND MEMORIALISATION by Susana Sabín-Fernández Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2010 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF LAW, ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES Doctor of Philosophy THE BASQUE REFUGEE CHILDREN OF THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR IN THE UK: MEMORY AND MEMORIALISATION By Susana Sabín-Fernández A vast body of knowledge has been produced in the field of war remembrance, particularly concerning the Spanish Civil War. However, the representation and interpretation of that conflictual past have been increasingly contested within the wider context of ‘recuperation of historical memory’ which is taking place both in Spain and elsewhere. -

Basques in the Americas from 1492 To1892: a Chronology

Basques in the Americas From 1492 to1892: A Chronology “Spanish Conquistador” by Frederic Remington Stephen T. Bass Most Recent Addendum: May 2010 FOREWORD The Basques have been a successful minority for centuries, keeping their unique culture, physiology and language alive and distinct longer than any other Western European population. In addition, outside of the Basque homeland, their efforts in the development of the New World were instrumental in helping make the U.S., Mexico, Central and South America what they are today. Most history books, however, have generally referred to these early Basque adventurers either as Spanish or French. Rarely was the term “Basque” used to identify these pioneers. Recently, interested scholars have been much more definitive in their descriptions of the origins of these Argonauts. They have identified Basque fishermen, sailors, explorers, soldiers of fortune, settlers, clergymen, frontiersmen and politicians who were involved in the discovery and development of the Americas from before Columbus’ first voyage through colonization and beyond. This also includes generations of men and women of Basque descent born in these new lands. As examples, we now know that the first map to ever show the Americas was drawn by a Basque and that the first Thanksgiving meal shared in what was to become the United States was actually done so by Basques 25 years before the Pilgrims. We also now recognize that many familiar cities and features in the New World were named by early Basques. These facts and others are shared on the following pages in a chronological review of some, but by no means all, of the involvement and accomplishments of Basques in the exploration, development and settlement of the Americas. -

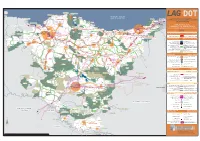

Laburpen Mapa (PDF, 3

Biotopo Gaztelugatxe Ruta del Vino y del Pescado - Senda del Mar BERMEO BAKIO GORLIZ LEMOIZ MUNDAKA KA N TA U R I I T S A S O A LAG BARRIKPALENTZIA DOT ELANTXOBE CASTRO URDIALES M A R C A N T Á B R IC O Euskal Autonomia Erkidegoko SUKARRIETA Senda del Mar MUNGIALDEA IBARRANGELU F R A N C I A SOPELANA BUSTURIA LURRALDE ANTOLAMENDUAREN MARURI-JATABE HONDARRIBIA URDULIZ MUNGIA EA LEKEITIO GIDALERROAK MURUETA Camino de Santiago (Costa) BERANGO ISPASTER EREÑO LAUKIZ GAUTEGIZ ARTEAGA BAYONNE ZIERBENA MENDEXA DIRECTRICES DE GETXO ARRIETA KORTEZUBI TXINGUDI - BIDASOA C A N TA B R IA PASAIA LEZO-GAINTZURIZKETA GERNIKA-LUMO GIZABURUAGA SANTURTZI LEZO ORDENACIÓN TERRITORIAL LEIOA FRUIZ GAMIZ-FIKA Reserva de la Biosfera de Urdaibai AMOROTO MUSKIZ NABARNIZ IRUN ABANTO Y CIERVANA/ABANTO-ZIERBANA ERRIGOITIA de la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco LOIU MUTRIKU ORTUELLA PORTUGALETE BUSTURIALDEA-ARTIBAI BERRIATUA ONDARROA Camino de Santiago (Interior) VALLE DE TRAPAGA-TRAPAGARAN SESTAO OIARTZUN ERANDIO ZUMAIA ZARAUTZ ERRENTERIA MORGA DEBA BARAKALDO ZAMUDIO AULESTI MIRAMÓN SONDIKA Biotopo Deba-Zumaia MUXIKA GETARIA Biotopo Inurritza 2019 DERIO ZAMUDIO BILBAO MENDATA MARKINA-XEMEIN P.N. Armañon USURBIL EREMU FUNTZIONALAK ÁREAS FUNCIONALES TRUCIOS-TURTZIOZ METROPOLITANO LASARTE-ORIA HERNANI BILBAO METROPOLITANO MUNITIBAR-ARBATZEGI GERRIKAITZ ORIO SOPUERTA LARRABETZU ITZIAR ÁREA DONOSTIA-SAN SEBASTIAN AIZARNAZABAL P.N. Aiako Harria Biotopo Zona Minera ETXEBARRIA MENDARO EREMU FUNTZIONALEN MUGAK DELIMITACIÓN DE AREAS FUNCIONALES ARTZENTALES ZIORTZA-BOLIBAR