Planning 1 Has ‘Gang Aft A-Gley’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

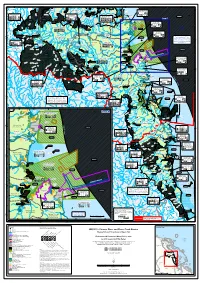

WQ1251 - Pioneer River and Plane Creek Basins Downs Mine Dam K ! R E Em E ! ! E T

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! %2 ! ! ! ! ! 148°30'E 148°40'E 148°50'E 149°E 149°10'E 149°20'E 149°30'E ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! S ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ° k k 1 e ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! re C 2 se C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! as y ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! M y k S ! C a ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ° r ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! r Mackay City estuarine 1 %2 Proserpine River Sunset 2 a u ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! g ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! e M waters (outside port land) ! m ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bay O k Basin ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! F C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! i ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! n Bucasia ! Upper Cattle Creek c Dalr -

ARI Magazine Issue 3 | 1 NEWS

ARI Australian Rivers Institute MAGAZINE Issue 3 SPECIAL FEATURES IN THIS ISSUE: Grand Challenges Feature Articless – The Murray Darling Basin Report – Waterways pollution – Biodiversity decline – Balancing water needs – Catchment resilience to climate change ARI Director Stuart Bunn appointed Earth Commissioner Great Barrier Reef recovery interventions—are we on target? ARI partnering to restore global wetlands Restoring fish habitat means enhanced fisheries Industry CONTENTS Director’s perspective 1 News 2 Grand challenges 4 Opinion, people and perspective 19 Life as a scientist 20 ECR spotlight 22 New staff 23 DIRECTOR’S WELCOME Professor Stuart Bunn We welcome you back to another edition of the Australian Rivers We explore the ‘grand challenge’ of balancing water needs Institute (ARI) Magazine. Over the past few months our staff for humans and nature. Our work in the Northern Australia have been active in strengthening research partnerships and Environmental Research Hub is featured, highlighting the establishing new connections across the globe. The importance important linkages between river flows, estuaries and the of connections, not only with fellow researchers, industry and fisheries and birdlife they sustain, and the implications of water government but also across ecosystems, forms a central theme resource development for agriculture. Professors Fran Sheldon of this edition of the Magazine. and David Hamilton discuss the recent review of the water sharing plan for the Barwon-Darling River system and Fran Associate Professor Anik Bhaduri has recently returned from further explores the broader issues of large-scale water India, where the Sustainable Water Future Programme hosted its diversion schemes in an opinion piece on the ‘Bradfield Scheme’. -

Report Template

2021-22 Budget Estimates – Appropriation Bill 2021 Report No. 13, 57th Parliament Economics and Governance Committee August 2021 Economics and Governance Committee Chair Mr Linus Power MP, Member for Logan Deputy Chair Mr Ray Stevens MP, Member for Mermaid Beach Members Mr Michael Crandon MP, Member for Coomera Mrs Melissa McMahon MP, Member for Macalister* Mr Daniel Purdie MP, Member for Ninderry Mr Adrian Tantari MP, Member for Hervey Bay *Mr Chris Whiting MP, Member for Bancroft, and Mr Don Brown MP, Member for Capalaba, participated as substitute members for Mrs Melissa McMahon MP, Member for Macalister, for the committee’s public hearing for the consideration of the 2021-22 portfolio budget estimates. Committee Secretariat Telephone +61 7 3553 6637 Fax +61 7 3553 6699 Email [email protected] Technical Scrutiny +61 7 3553 6601 Secretariat Committee webpage www.parliament.qld.gov.au/EGC Acknowledgements The committee thanks the Premier and Minister for Trade; Treasurer and Minister for Investment; Minister for Tourism Industry Development and Innovation and Minister for Sport; and portfolio statutory entities for their assistance. The committee also acknowledges the assistance provided by the departmental officers and other officials who contributed to the work of the committee during the estimates process. All web address references were correct as at 18 August 2021. 2021–22 Budget Estimates Contents Chair’s foreword ii Abbreviations iii 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Role of the committee 1 1.2 Inquiry process 1 1.3 Aim of this report -

Preliminary Business Case

HUGHENDEN IRRIGATION PROJECT CORPORATION PTY LTD Preliminary Business Case Hughenden Irrigation Project Volume One – Study Report FEBRUARY 2020 HUGHENDEN IRRIGATION PROJECT CORPORATION PTY LTD PRELIMINARY BUSINESS CASE DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared on behalf of and for the use of Hughenden Irrigation Project Corporation Pty Ltd and the Australian Government and is subject to and issued in accordance with Hughenden Irrigation Project Corporation Pty Ltd instruction to Engeny Water Management (Engeny). Engeny accepts no liability or responsibility for any use of or reliance upon this report by any third party. JOB NO. AND PROJECT NAME: M7220_003 HIP Preliminary Business Case DOC PATH FILE: M:\Projects\M7000_Miscellaneous Clients\M7220_002 HIP Prelim Business Case\07 Deliv\Docs\Report\Revs\Master Report\M7220_003-REP-001-0 Prelim Business Case - Master Report.docx REV DESCRIPTION AUTHOR REVIEWER PROJECT APPROVER / DATE MANAGER PROJECT DIRECTOR Rev 0 Client Issue Jim Pruss Andrew Vitale Andrew Vitale Aaron Hallgath 14 February 2020 Signatures M7220_003-REP-001 Page ii Rev 0 : 14 February 2020 HUGHENDEN IRRIGATION PROJECT CORPORATION PTY LTD PRELIMINARY BUSINESS CASE CONTENTS CONTENTS III APPENDICES XI LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................. XII LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................ XV 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................ -

Published on DNRME Disclosure Log RTI Act 2009

CTS No. 31998/19 DATE DUE TO DLO 18/12/2019 ELECTORATE OFFICE Ipswich Electorate Office NAME OF CONSTITUENT/MEMBER OF PUBLIC Sch 4 - Personal Information If applicable ISSUE Linking dams across Queensland RESPONDING OFFICER Name: Darren Thompson Author Position: Team Leader Business Unit: Water Supply, Natural Resources Division Phone: 3166 0154 FINAL APPROVAL Name: Trevor Dann DG/DDG/ED Position: Acting Executive Director Log Business Unit: Water Supply, Natural Resources Division Phone: 3137 4285 PLEASE NOTE: This advice is provided for the information of the Office of the Minister for Natural Resources, Mines and Energy to assist in preparing a response to the Electorate Office SUGGESTED RESPONSE TO ELECTORATE OFFICE Linking Dams Disclosure • Though the concept of large scale systems similar to those of the Bradfield Scheme have significant challenges, there may be an opportunity to undertake targeted improvements to regional connectivity where demand and supply characteristics are right. • There are already examples of this type of connectivity2009 that exist across the state where dams and pipelines provide water to where a demonstrated demand for water exists including Burdekin Haughton Water Supply scheme to Ross River Dam, the Burdekin to Moranbah pipeline and the North West pipeline near Mount Isa. DNRMEAct • The Queensland Government is ready to have a conversation with the Australian Government and its new National Water Grid Authorityon on a range of water infrastructure proposals including the opportunity for further increasing regional connectivityRTI where it makes sense (e.g. available supply within responsible limits commensurate with Queensland Water Plans and demonstrated demand for the water). • This could include identifying opportunities to explore the concept of connecting bulk water storages to where there is a clear demand for water at a price commensurate with the costs providing the water. -

Sunwater 2019-20 Annual Report

Annual Report 2019-20 ISSN 2652-6492 © The State of Queensland (Sunwater Ltd) 2020. Published by Sunwater Ltd, September 2020. Green Square North, Level 9, 515 St Pauls Terrace, Fortitude Valley, Queensland 4006. 2. Highlights | Page 2 About this report We are pleased to present this annual report to provide an overview of Sunwater Limited’s (Sunwater) financial and non-financial performance for the 12 months to 30 June 2020. This report includes a summary of the activities carried out to meet the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) set out in Sunwater’s 2019–20 Statement of Corporate Intent (SCI 2019—20), which is our performance agreement with our shareholding Ministers. This report aims to provide information to meet the needs of Sunwater’s broad range of stakeholders, including our customers, state and local government partners, delivery partners, current and future employees and other commercial stakeholders. An electronic version is available on the Sunwater website at www.sunwater.com.au/about/publications. We invite your feedback on this report. If you wish to comment, please contact our Customer Support team by calling 13 15 89 or emailing [email protected]. Scope This report covers all Sunwater operations in Queensland and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) in Australia, including dams, weirs, barrages, water channels, pumping stations, pipelines, water treatment plants and our physical hydraulic modelling laboratory at Rocklea in Brisbane. We acknowledge the traditional owners We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land on which we operate and recognise their continuing connection to land, waters and community. We pay our respects to them and their cultures, and to elders both past and present. -

Economic Assessment of Urannah Dam

Photo credit: Photograph: Jeff Tan Economic Assessment of Urannah Dam: An evaluation and reassessment of the preliminary business case and benefit cost analysis Prepared on behalf of the Mackay Conservation Group by Andrew Buckwell, Altus Impact Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................................................. I ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................................. II DEFINITION OF KEY TERMS .................................................................................................................................. III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................................... IV 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Proposal ................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Approach .................................................................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Policy framework for bulk water assets ................................................................................................. 2 1.4 Social benefit cost -

Capital Program 2020 Update Copyright Disclaimer This Publication Is Protected by the Copyright Act 1968

Capital Program 2020 update Copyright Disclaimer This publication is protected by the Copyright Act 1968. While every care has been taken in preparing this publication, to the extent permitted by law, the State of Queensland accepts Licence no responsibility and disclaims all liability (including without limitation, liability in negligence) for all expenses, losses This work, except as identified below, is (including direct and indirect loss), damages and costs incurred licensed by Queensland Treasury under a as a result of decisions or actions taken as a result of any data, Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative information, statement or advice, expressed or implied, contained Works (CC BY-ND) 4.0 Australia licence. To view a copy of this within. To the best of our knowledge, the content was correct at the licence, visit: http://creativecommons.org.au/ time of publishing. You are free to copy and communicate this publication, Copies of this publication are available on our website at as long as you attribute it as follows: www.treasury.qld.gov.au and further copies are available © State of Queensland, Queensland Treasury, August 2020 upon request to: Third party material that is not licensed under a Creative Commons Queensland Treasury licence is referenced within this publication. All content not PO Box 15009, City East, QLD 4000 licensed under a Creative Commons licence is all rights reserved. Please contact Queensland Treasury / the copyright owner if you Phone: 13 QGOV (13 7468) wish to use this material. Email: [email protected] Web: www.treasury.qld.gov.au The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders of all cultural and linguistic backgrounds. -

Adelaide Public Hearing Transcript

SPARK AND CANNON Telephone: Adelaide (08) 8110 8999 TRANSCRIPT Hobart (03) 6220 3000 Melbourne (03) 9248 5678 OF PROCEEDINGS Perth (08) 6210 9999 Sydney (02) 9217 0999 _______________________________________________________________ PRODUCTIVITY COMMISSION INQUIRY INTO AUSTRALIA'S URBAN WATER SECTOR DR W. CRAIK, Presiding Commissioner DR W. MUNDY, Associate Commissioner TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS AT ADELAIDE ON TUESDAY, 7 DECEMBER 2010, AT 9 AM Continued from 30/11/10 in Melbourne Urban 243 ur071210.doc INDEX Page CITY OF SALISBURY: COLIN PITMAN 244-258 AUSTRALIAN ACADEMY OF TECHNOLOGICAL SCIENCES AND ENGINEERING: JOHN RADCLIFFE 259-270 WATER QUALITY RESEARCH AUSTRALIA: JODIEANN DAWE 271-281 DEPARTMENT FOR WATER: JULIA GRANT STEVEN MORTON 282-305 CSIRO LAND AND WATER: PETER DILLON 306-313 7/12/10 Urban (i) DR CRAIK: Good morning. Welcome to the public hearings for the Productivity Commission inquiry into Australia's urban water sector following the release of the issues paper in late September. My name is Wendy Craik and I'm the presiding commissioner on this inquiry. The other commissioner on this inquiry is Associate Commissioner Warren Mundy. The purpose of this round of hearings is to get comment and feedback on the issues paper and facilitate public participation in the inquiry process more generally. Prior to these hearings in Adelaide we have met with interested parties and individuals throughout Australia and during October and last week we held roundtables in Perth, Sydney and Melbourne. Our public hearings commenced in Sydney on 9 November, followed by Canberra on 29 November and Melbourne on 30 November. Following today's proceedings, hearings will also be held in Perth and Hobart and we'll then be working towards completing a draft report for publication sometime in March 2011, having considered all of the evidence presented at the hearings and in submissions as well as other informal discussions. -

Sunwater Irrigation Price Review: 2012-17 Volume 2 Pioneer River Water Supply Scheme

Draft Report SunWater Irrigation Price Review: 2012-17 Volume 2 Pioneer River Water Supply Scheme November 2011 Level 19, 12 Creek Street Brisbane Queensland 4000 GPO Box 2257 Brisbane Qld 4001 Telephone (07) 3222 0555 Facsimile (07) 3222 0599 [email protected] www.qca.org.au © Queensland Competition Authority 2011 The Queensland Competition Authority supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of information. However, copyright protects this document. The Queensland Competition Authority has no objection to this material being reproduced, made available online or electronically but only if it is recognised as the owner of the copyright and this material remains unaltered. Queensland Competition Authority Submissions SUBMISSIONS This report is a draft only and is subject to revision. Public involvement is an important element of the decision-making processes of the Queensland Competition Authority (the Authority). Therefore submissions are invited from interested parties. The Authority will take account of all submissions received. Written submissions should be sent to the address below. While the Authority does not necessarily require submissions in any particular format, it would be appreciated if two printed copies are provided together with an electronic version on disk (Microsoft Word format) or by e-mail. Submissions, comments or inquiries regarding this paper should be directed to: Queensland Competition Authority GPO Box 2257 Brisbane QLD 4001 Telephone: (07) 3222 0557 Fax: (07) 3222 0599 Email: [email protected] The closing date for submissions is 23 December 2011. Confidentiality In the interests of transparency and to promote informed discussion, the Authority would prefer submissions to be made publicly available wherever this is reasonable. -

Water Services Monthly Review December 2018 – January 2019 Engineering & Commercial Infrastructure Monthly Review > December 2018 and January 2019

Engineering and Commercial Infrastructure - Water Services Monthly Review December 2018 – January 2019 Engineering & Commercial Infrastructure Monthly Review > December 2018 and January 2019 OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................................. 3 SAFETY ................................................................................................................................ 4 1.1. Incident Statistics ........................................................................................................ 4 1.2. Lost Time Injuries ........................................................................................................ 4 FINANCE .............................................................................................................................. 6 2.1. Water and Wastewater Financial Fund Report ........................................................... 6 2.2. Operating Result for Water and Sewerage Fund ........................................................ 7 CUSTOMER SERVICES ................................................................................................... 7 3.1. Requests ..................................................................................................................... 7 3.2. Request Types ............................................................................................................ 8 3.3. Plumbing Applications ................................................................................................ -

Inquiry Into Additional Water Supplies for South East Queensland

16 Varley Rd, south. Glenwood. Queensland. 4570 telephone (07) 54857324 E-Mail [email protected] 2nd April 2007. Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport E-mail www.aph.gov.au/senate_rrat Re – WATER SUPPLIES FOR SOUTHEAST QUEENSLAND- TRAVESTON DAM. To whom it may concern. I live in the Tiaro Shire, downstream from the proposed Traveston Dam site. Much thought has gone into my proposal, as more dams in Southeast Queensland will not alleviate the current water crisis. There are sufficient dams in Southeast Queensland to service the population, all that is necessary is the water! Therefore, a variation of the Bradfield Scheme is envisaged, to alleviate not only future water crises in Southeast Queensland, but to assist in the regeneration of the Murray-Darling river system. It is a huge undertaking, but viable. A pipeline down the Queensland coast was considered but the obstacles that would be encountered viz; population density and deep and wide rivers to cross, tended to negate that proposal. Whereas an inland pipeline would not cause a great deal of disruption to the general population and is a more direct route, and will be there for many generations to come. Also as our population increases and spreads north and west from Southeast Queensland, as it must, the future water supply for those people will be assured. SUMMARY INTRODUCTION – The history of the Bradfield Scheme. PLANNED PROPOSAL- Description of the variation of the Bradfield Scheme envisaged in this proposal to supplement the water in the dams of SE Queensland. FURTHER BENEFITS OF THE PROPOSAL- including the regeneration of the Murray-Darling rivers system.