IN the ANTIPODES Rotary in Australia and New Zealand 1921

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 1 Comprehensive International Points List

Table 1 Comprehensive International Points List FCC ITU-T Country Region Dialing FIPS Comments, including other 1 Code Plan Code names commonly used Abu Dhabi 5 971 TC include with United Arab Emirates Aden 5 967 YE include with Yemen Admiralty Islands 7 675 PP include with Papua New Guinea (Bismarck Arch'p'go.) Afars and Assas 1 253 DJ Report as 'Djibouti' Afghanistan 2 93 AF Ajman 5 971 TC include with United Arab Emirates Akrotiri Sovereign Base Area 9 44 AX include with United Kingdom Al Fujayrah 5 971 TC include with United Arab Emirates Aland 9 358 FI Report as 'Finland' Albania 4 355 AL Alderney 9 44 GK Guernsey (Channel Islands) Algeria 1 213 AG Almahrah 5 967 YE include with Yemen Andaman Islands 2 91 IN include with India Andorra 9 376 AN Anegada Islands 3 1 VI include with Virgin Islands, British Angola 1 244 AO Anguilla 3 1 AV Dependent territory of United Kingdom Antarctica 10 672 AY Includes Scott & Casey U.S. bases Antigua 3 1 AC Report as 'Antigua and Barbuda' Antigua and Barbuda 3 1 AC Antipodes Islands 7 64 NZ include with New Zealand Argentina 8 54 AR Armenia 4 374 AM Aruba 3 297 AA Part of the Netherlands realm Ascension Island 1 247 SH Ashmore and Cartier Islands 7 61 AT include with Australia Atafu Atoll 7 690 TL include with New Zealand (Tokelau) Auckland Islands 7 64 NZ include with New Zealand Australia 7 61 AS Australian External Territories 7 672 AS include with Australia Austria 9 43 AU Azerbaijan 4 994 AJ Azores 9 351 PO include with Portugal Bahamas, The 3 1 BF Bahrain 5 973 BA Balearic Islands 9 34 SP include -

ISO Country Codes

COUNTRY SHORT NAME DESCRIPTION CODE AD Andorra Principality of Andorra AE United Arab Emirates United Arab Emirates AF Afghanistan The Transitional Islamic State of Afghanistan AG Antigua and Barbuda Antigua and Barbuda (includes Redonda Island) AI Anguilla Anguilla AL Albania Republic of Albania AM Armenia Republic of Armenia Netherlands Antilles (includes Bonaire, Curacao, AN Netherlands Antilles Saba, St. Eustatius, and Southern St. Martin) AO Angola Republic of Angola (includes Cabinda) AQ Antarctica Territory south of 60 degrees south latitude AR Argentina Argentine Republic America Samoa (principal island Tutuila and AS American Samoa includes Swain's Island) AT Austria Republic of Austria Australia (includes Lord Howe Island, Macquarie Islands, Ashmore Islands and Cartier Island, and Coral Sea Islands are Australian external AU Australia territories) AW Aruba Aruba AX Aland Islands Aland Islands AZ Azerbaijan Republic of Azerbaijan BA Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina BB Barbados Barbados BD Bangladesh People's Republic of Bangladesh BE Belgium Kingdom of Belgium BF Burkina Faso Burkina Faso BG Bulgaria Republic of Bulgaria BH Bahrain Kingdom of Bahrain BI Burundi Republic of Burundi BJ Benin Republic of Benin BL Saint Barthelemy Saint Barthelemy BM Bermuda Bermuda BN Brunei Darussalam Brunei Darussalam BO Bolivia Republic of Bolivia Federative Republic of Brazil (includes Fernando de Noronha Island, Martim Vaz Islands, and BR Brazil Trindade Island) BS Bahamas Commonwealth of the Bahamas BT Bhutan Kingdom of Bhutan -

Political Agency and Youth Subjectivities in Tactic, Guatemala

Enacting Youth: political agency and youth subjectivities in Tactic, Guatemala By Lillian Tatiana Paz Lemus Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Anthropology August, 9th, 2019 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Edward F. Fischer, Ph.D. Lesley Gill, Ph.D. Arthur Demarest, Ph.D. Debra Rodman, Ph.D. DEDICATION To the loving memory of my grandmother, Marta Guzmán de Lemus, who I miss daily. Tactic will always be our home because she made sure we were always loved and fed under her roof. I am very proud to be introduced as her granddaughter whenever I meet new people in town. To Edelberto Torres-Rivas. He wanted to hear about young people’s engagement in our political life, but I was never able to show him the final text. We would have discussed so much over this. I will forever miss our banter and those long meals along our friends. To the many young Guatemalans who strive to make our country a better place for all. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Through the long journey of the doctoral studies, I have had the great fortune of being surrounded by wonderful people who provided the needed support and help to see this project to fruition. Dissertations are never an individual accomplishment, and while the mistakes are entirely my own, there is much credit to give the many people who interacted with me through the years and made this possible First, I would like to express my gratitude to my advisor, Professor Edward F. -

From Podes to Antipodes: New Dimensions in Mapping Global Time, Cost, and Distance

From Podes to Antipodes: New Dimensions in Mapping Global Time, Cost, and Distance by Matthew A. Zook* and Stanley D. Brunn** Department of Geography University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40506-0027 *[email protected] **[email protected] Paper prepared for Specialist Workshop on Globalization in the World-System: Mapping Change over Time University of California, Riverside February 7-8, 2004 DRAFT – DRAFT - DRAFT – DRAFT - DRAFT - DRAFT Do not distribute or reproduce DRAFT – DRAFT - DRAFT – DRAFT - DRAFT - DRAFT Table of Contents Thinking about Time, Space and Distance ................................................................................. 2 Representations of Time, Space and Distance............................................................................ 3 Thinking about and Representing Global Air Travel............................................................... 5 Description of the Data and its Generation................................................................................ 6 Data Analysis................................................................................................................................. 8 Summation of Physical, Cost and Time Distance....................................................................... 9 Explaining Cost and Time Distance ......................................................................................... 10 Representing Physical, Cost and Time Distance ...................................................................... 11 Conclusions and Future Directions .......................................................................................... -

Floating on a Malayan Breeze : Travels in Malaysia and Singapore Pdf, Epub, Ebook

FLOATING ON A MALAYAN BREEZE : TRAVELS IN MALAYSIA AND SINGAPORE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sudhir Thomas Vadaketh | 324 pages | 18 Dec 2012 | Hong Kong University Press | 9789888139316 | English | Hong Kong, Hong Kong Floating on a Malayan Breeze : Travels in Malaysia and Singapore PDF Book This is probably because of my race and character. A must read for anyone now working in this part of the world for a good appreciation of the peculiarities and achievements of the two countries. Bucking this economic pragmatism is ridiculously difficult. Index pp. The only North Indian group that is widely accepted and instantly recognisable—because of its critical mass and distinctive dress—is the Sikh Punjabis. Forty-five years ago Singapore separated from Malaysia. Terence Loading In Floating , there is also a chapter dedicated to discussing the effects Mainland Chinese workers are having on the Singaporean society and labour force. She is a first-generation Singaporean Marwari, people who hail from Rajasthan in North-west India, about as far as you can get geographically and culturally from Kerala. Malaysia has given preference to the majority Malay Muslims — the bumiputera , or sons of the soil. Bounced around a bit too much for me as well, but it was my first good entre into that part of the world. He writes that "since , Malaysia and Singapore have tried hard to create distinct nation states. Immigration, meanwhile, is a complex issue that deserves its own piece. Since then, a combination of forces--including policy missteps by the ruling parties, the emergence of more credible opposition candidates, and the widening of political space through the internet--has blown the lid off our hitherto politically apathetic countries" p. -

Level of Youth Voice in the Decision-Making Process Within the 4-H Youth Development Program As Perceived by State 4-H Program L

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Level of youth voice in the decision-making process within the 4-H youth development program as perceived by State 4-H Program Leaders, State 4-H Youth Development Specialists, and 4-H Agents/ Educators Todd Anthony Tarifa Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Human Resources Management Commons Recommended Citation Tarifa, Todd Anthony, "Level of youth voice in the decision-making process within the 4-H youth development program as perceived by State 4-H Program Leaders, State 4-H Youth Development Specialists, and 4-H Agents/Educators" (2006). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3484. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3484 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. LEVEL OF YOUTH VOICE IN THE DECISION-MAKING PROCESS WITHIN THE 4-H YOUTH DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM AS PERCEIVED BY STATE 4-H PROGRAM LEADERS, STATE 4-H YOUTH DEVELOPMENT SPECIALISTS, AND 4-H AGENTS/EDUCATORS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Human Resource Education and Workforce Development by Todd A. Tarifa B. S., Louisiana State University, 1996 M. -

Antipodes Global Fund

Antipodes Asia Fund ARSN 096 451 393 APIR IOF0203AU MONTHLY REPORT | 30 April 2021 Commentary Global equity strength continued in April as a further supportive US fiscal Key contributors included: backdrop boosted sentiment (+2.9). Investors exhibited a preference for • Consumer Defensive cluster, notably sportswear name Li Ning amidst momentum and growth over low multiple - or value - stocks with an ongoing consumer backlash against foreign competitors boycotting Communication Services and Information Technology outperforming. Cyclical the use of cotton from the Xinjiang region, and Wuliangye which reported sectors such as Materials, Financials and Consumer Discretionary were also strong revenues amidst supply constraints from a key competitor. strong while Energy was the major laggard. • Industrials, notably LG Chem on strong results across its chemicals, electronics and batteries businesses, and POSCO resulting from US equities (+3.9%) outperformed as US technology giants resumed strength in the price of steel. leadership, helped by stabilising yields. President Biden's speech to congress • Hardware cluster, notably MediaTek which reported strong first quarter signalled further fiscal spending plans funded by new tax proposals. Europe growth in revenues, primarily in 5G handset chip sales, while also lifting (+3.1%) marginally outperformed as the trajectory for COVID-19 vaccinations near term guidance, and TSMC which also lifted 2021 revenue guidance. improved. Alchip was a notable exception following a US decision to add Chinese supercomputing entities with links to the Chinese military, which included Asia (-0.4%) underperformed as Japan (-2.9%) weighed due to rising COVID- Alchip clients, to its economic blacklist. 19 infections, a slow vaccine rollout, and a new state of emergency. -

Youth Empowerment for Sustainable Development: the Role of Entrepreneurship Education for Out-Of-School Youth

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Poverty, Investment and Development - An Open Access International Journal Vol.5 2014 Youth Empowerment for Sustainable Development: The Role of Entrepreneurship Education for Out-of-School Youth Kolade T. T., Towobola W. L., Oresanya T. O., Ayeni J. O., Omodewu O. S. Yaba College of Technology, Yaba, Lagos. [email protected] Abstract Nigeria has one of the poorest sets of national development indices in the world and it is widely believed that the underdevelopment of human capacity is a major factor contributing to Nigeria’s underdevelopment. Demographic segregation of the Nigerian population indicates that youths form the largest segment of the population. Hence, developmental efforts must target and/or capture the youthful population to have tangible and meaningful impact. The term youth empowerment is broadly employed to explain efforts aimed at providing coping skills and an enabling environment for youths to lead decent lives and contribute meaningfully to national development. An emerging trend in youth empowerment in Nigeria is entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship education assumed importance against the background of poverty, widespread unemployment and the need to shift the attention of the citizenry away from white collar jobs and government patronage. This study highlights the importance of youth empowerment towards attaining sustainable development of the Nigerian nation. It examines the place of entrepreneurship education in the empowerment of youths, and attempts to identify missing links in the execution of entrepreneurship education initiatives in Nigeria. -

Growing to Greatness 2008 the State of Service-Learning

Growing to Greatness 2008 THE STATE OF SERVICE-LEARNING A report from the National Youth Leadership Council WITH FUNDING PROVIDED BY Service-Learning by the Numbers 299.4 Estimated U.S. population in millions.1 4.7 Estimated millions of U.S. K-12 students 54 Percentage of national 2006 General engaged in service-learning.2 Election turnout of voters age 30 and older.1 53.3 Estimated U.S. population in millions of youth (ages 5-17).1 1.3 Number in millions of 2005-2006 25 Percentage of national 2006 K-12 students supported by Federal General Election turnout of voters 17.8 Percentage of youth in the Learn and Serve America grants.3 under the age of 30.1 total U.S. population.1 43 Investment in 2005-2006 Learn and 41 Percentage of former service-learning Serve programs in millions of dollars.3 youths (ages 18-29) who voted in a local, state, or national election.7 Campus Compact member colleges 1,045 4:1 Monetary value of service provided by Learn 5 or universities. and Serve participants to their communities, 57 Percentage of former service-learning compared to Learn and Serve money spent.4 youths (ages 18-29) who report that voting Service hours in millions logged by 2005-2006 377 7 5 in elections is important. Campus Compact participants. 86 Percentage of U.S. principals who reported that service-learning has a positive impact 92 Percentage of principals from U.S. schools 7.1 Monetary value in billions of dollars on the larger community’s view of youths with service-learning programs who reported of service performed annually by as resources.2 that service-learning has a positive impact Campus Compact participants.5 on students’ civic engagement.2 83 Percentage of U.S. -

Download Download

Number 63, Spring 2009 cartographic perspectives 69 its chapters, the text is to be highly recommended as generations, it was gradually supplemented by new encouraging further work in this realm. Because of this knowledge, which led to the need to distinguish book, and other publications by Knowles, Hillier, Bol, ancient from modern knowledge. For Hiatt, there is Gregory, and others, I look forward to future publica- a clear and consistent, if not always smooth, line of tions in the use of GIS for History. thought extending from the ancient period through the early modern. It is characterized by ancient writings being retold and supplemented, not simply to preserve the originals, but to give them prolonged credibility by Terra Incognita: Mapping the Antipodes before 1600 making them appear to foretell subsequent discover- By Alfred Hiatt ies. University of Chicago Press, 2008 The third theme explores periodization, and Hiatt’s 298 pages, 8 color plates, 47 grayscale figures conviction that conceptions of the world do not easily Hardbound (ISBN 13: 978-0-226-33303-8) fit standard period delimiters. He observes that, while change did occur, “[W]hy that change occurred will Reviewed by: Jonathan F. Lewis not be enlightening if it falls back on banalities about Benedictine University inherently “antique,” “medieval,” or “modern” ways of viewing the world” ( 9). For Hiatt, the medieval pe- Terra Incognita examines and explains the initial ap- riod witnessed not the end of a view of the world in- pearance and subsequent evolution of European per- formed by ancient writers, but rather a dialogue with spectives on remote, unvisited portions of the globe. -

Antipodes: in Search of the Southern Continent Is a New History of an Ancient Geography

ANTIPODES In Search of the Southern Continent AVAN JUDD STALLARD Antipodes: In Search of the Southern Continent is a new history of an ancient geography. It reassesses the evidence for why Europeans believed a massive southern continent existed, About the author and why they advocated for its Avan Judd Stallard is an discovery. When ships were equal historian, writer of fiction, and to ambitions, explorers set out to editor based in Wimbledon, find and claim Terra Australis— United Kingdom. As an said to be as large, rich and historian he is concerned with varied as all the northern lands both the messy detail of what combined. happened in the past and with Antipodes charts these how scholars “create” history. voyages—voyages both through Broad interests in philosophy, the imagination and across the psychology, biological sciences, high seas—in pursuit of the and philology are underpinned mythical Terra Australis. In doing by an abiding curiosity about so, the question is asked: how method and epistemology— could so many fail to see the how we get to knowledge and realities they encountered? And what we purport to do with how is it a mythical land held the it. Stallard sees great benefit gaze of an era famed for breaking in big picture history and the free the shackles of superstition? synthesis of existing corpuses of That Terra Australis did knowledge and is a proponent of not exist didn’t stop explorers greater consilience between the pursuing the continent to its sciences and humanities. Antarctic obsolescence, unwilling He lives with his wife, and to abandon the promise of such dog Javier. -

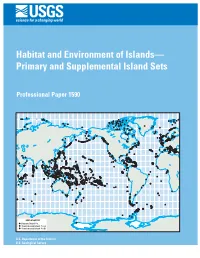

Habitat and Environment of Islands— Primary and Supplemental Island Sets

Habitat and Environment of Islands— Primary and Supplemental Island Sets Professional Paper 1590 EXPLANATION Primary Island Set Supplemental Island Set A Supplemental Island Set B U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey HABITAT AND ENVIRONMENT OF ISLANDS Primary and Supplemental Island Sets By N.C. Matalas and Bernardo F. Grossling U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1590 U.S. Department of the Interior GALE A. NORTON, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Government Reston, Virginia 2002 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Matalas, Nicholas C., 1930– Habitat and environment of islands : primary and supplemental island sets / by N.C. Matalas and Bernardo F. Grossling. p. cm. — (U.S. Geological Survey professional paper ; 1590) Includes bibliographical references (p. ). ISBN 0-607-99508-4 1. Island ecology. 2. Habitat (Ecology) I. Grossling, Bernardo F., 1918– II. Title. III. Series. QH541.5.I8 M27 2002 577.5’2—dc21 2002035440 For sale by the U.S. Geological Survey Information Services Box 25286, Federal Center, Denver, CO 80225 PREFACE The original intent of the study was to develop a first-order synopsis of island hydrology with an inte- grated geologic basis on a global scale. As the study progressed, the aim was broadened to provide a frame- work for subsequent assessments on large regional or global scales of island resources and impacts on