Nber Working Paper Series the Rise of Income And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compendium of Federal Estate Tax and Personal W Ealth Studies

A Comparison of Wealth Estimates for America’s Wealthiest Decedents Using Tax Data and Data from the Forbes 400 Brian Raub, Barry Johnson, and Joseph Newcomb, Statistics of Income, IRS1 Presented in “New Research on Wealth and Estate Taxation” Introduction Measuring the wealth of the Nation’s citizens has long been a topic of interest among researchers and policy planners. Unfortunately, such measurements are difficult to make because there are few sources of data on the wealth holdings of the general population, and most especially of the very rich. Two of the better-known sources of wealth statistics are the household estimates derived from the Federal Reserve Board of Governor’s Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) (Kenneckell, 2009) and estimates of personal wealth derived from estate tax Chapter 7 — Studies Linking Income & Wealth returns, produced by the Statistics of Income Division (SOI) of the Internal Revenue Service (Raub, 2007). In addition, Forbes magazine annually has produced a list, known as the Forbes 400, that includes wealth estimates for the 400 wealthiest individuals in the U.S. While those included on the annual Forbes 400 list represent less than .0002 percent of the U.S. population, this group holds a relatively large share of the Nation’s wealth. For example, in 2007, the almost $1.6 trillion in estimated collective net worth owned by the Forbes 400 accounted for about 2.3 percent of total U.S. household net worth (Kopczuk and Saez, 2004). This article focuses on the estimates of wealth produced for the Forbes 400 and their relationship to data collected by SOI (see McCubbin, 1994, for results of an earlier pilot of this study). -

Warren Wealth Tax Would Have Raised $114 Billion in 2020 from Nation’S 650 Billionaires Alone

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: MARCH 1, 2021 WARREN WEALTH TAX WOULD HAVE RAISED $114 BILLION IN 2020 FROM NATION’S 650 BILLIONAIRES ALONE Ten-Year Revenue Total Would Be $1.4 Trillion Even as Billionaire Wealth Continued to Grow WASHINGTON, D.C. – America’s billionaires would owe a total of about $114 billion in wealth tax for 2020 if the Ultra-Millionaire Tax Act introduced today by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) and Rep. Brendan Boyle (D-PA) had been in effect last year, based on Forbes billionaire wealth data analyzed by Americans for Tax Fairness (ATF) and the Institute for Policy Studies Project on Inequality (IPS). The ten-year revenue total would be about $1.4 trillion, and yet U.S. billionaire wealth would continue to grow. (The 10-year revenue estimate is explained below.) Billionaire wealth is top-heavy, so just the richest 15 own one-third of all the wealth and would thus be liable for about a third of the wealth tax (see table below). Under the Ultra-Millionaire Tax Act, those 15 richest billionaires would have paid a total of $40 billion in wealth tax for the 2020 tax year, but their projected collective wealth would have still increased by more than half (53%), only slightly lower than their actual 58% increase in wealth without the wealth tax, since March 18, 2020, the rough beginning of the pandemic and the start date for this analysis. Full billionaire data is here. Some examples from the top of the list: Jeff Bezos would pay $5.7 billion in wealth taxes for 2020, lowering the size of his fortune from $191.2 billion to $185.5 billion, or 5%, but it still would have increased by two-thirds from March 18 to the end of the year. -

This Year's Edition

CO-AUTHORS: Chuck Collins directs the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies, where he also co-edits Inequality.org. His most recent book is Is Inequality in America Irreversible? from Polity Press and in 2016 he published Born on Third Base. Other reports and books by Collins include Reversing Inequality: Unleashing the Transformative Potential of An More Equal Economy and 99 to 1: How Wealth Inequality is Wrecking the World and What We Can Do About It. His 2004 book Wealth and Our Commonwealth, written with Bill Gates Sr., makes the case for taxing inherited fortunes. Josh Hoxie directs the Project on Opportunity and Taxation at the Institute for Policy Studies and co- edits Inequality.org. He co-authored a number of reports on topics ranging from economic inequality, to the racial wealth divide, to philanthropy. Hoxie has written widely on income and wealth maldistribution for Inequality.org and other media outlets. He worked previously as a legislative aide for U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders. Acknowledgements: We received significant assistance in the production of this report. We would like to thank our colleagues at IPS who helped us throughout the report. The Institute for Policy Studies (www.IPS-dc.org) is a multi-issue research center founded in 1963. The Program on Inequality and the Common Good was founded in 2006 to draw attention to the growing dangers of concentrated wealth and power, and to advocate policies and practices to reverse extreme inequalities in income, wealth, and opportunity. The Inequality.org website (http://inequality.org/) provides an online portal into all things related to the income and wealth gaps that so divide us. -

Billionaire Bonanza 2017: the Forbes 400 and the Rest of Us

CO-AUTHORS: Chuck Collins directs the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies, where he also co-edits Inequality.org. His most recent book: Born on Third Base: A One Percenter Makes the Case for Tackling Inequality, Bringing Wealth Home, and Committing to the Common Good. Other reports and books by Collins include Reversing Inequality: Unleashing the Transformative Potential of An More Equal Economy and 99 to 1: How Wealth Inequality is Wrecking the World and What We Can Do About It. His 2004 book Wealth and Our Commonwealth, written with Bill Gates Sr., makes the case for taxing inherited fortunes, and his The Moral Measure of the Economy, written with Mary Wright, explores Christian ethics and economic life. Collins co-founded the Patriotic Millionaires and United for a Fair Economy. Josh Hoxie directs the Project on Opportunity and Taxation at the Institute for Policy Studies and co- edits Inequality.org. He co-authored a number of reports on topics ranging from economic inequality, to the racial wealth divide, to philanthropy. Hoxie has written widely on income and wealth maldistribution for Inequality.org and other media outlets. He worked previously as a legislative aide for U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders. Graphic Design: Kenneth Worles, Jr. Data Analyst: Amanda Page-Hoongrajok, University of Massachusetts Amherst. Acknowledgements: We received significant assistance in the production of this report. We would like to thank our colleagues at IPS who helped us throughout the report development process, especially Jessicah Pierre, Sam Pizzigati, and Sarah Anderson. The Institute for Policy Studies (www.IPS-dc.org) is a multi-issue research center that has been conducting path-breaking research on inequality for more than 20 years. -

Current Affairs Capsule for SBI/IBPS/RRB PO Mains Exam 2021 – Part 2

Current Affairs Capsule for SBI/IBPS/RRB PO Mains Exam 2021 – Part 2 Important Awards and Honours Winner Prize Awarded By/Theme/Purpose Hyderabad International CII - GBC 'National Energy Carbon Neutral Airport having Level Airport Leader' and 'Excellent Energy 3 + "Neutrality" Accreditation from Efficient Unit' award Airports Council International Roohi Sultana National Teachers Award ‘Play way method’ to teach her 2020 students Air Force Sports Control Rashtriya Khel Protsahan Air Marshal MSG Menon received Board Puruskar 2020 the award NTPC Vallur from Tamil Nadu AIMA Chanakya (Business Simulation Game)National Management Games(NMG)2020 IIT Madras-incubated Agnikul TiE50 award Cosmos Manmohan Singh Indira Gandhi Peace Prize On British broadcaster David Attenborough Chaitanya Tamhane’s The Best Screenplay award at Earlier, it was honoured with the Disciple Venice International Film International Critics’ Prize awarded Festival by FIPRESCI. Chloe Zhao’s Nomadland Golden Lion award at Venice International Film Festival Aditya Puri (MD, HDFC Bank) Lifetime Achievement Award Euromoney Awards of Excellence 2020. Margaret Atwood (Canadian Dayton Literary Peace Prize’s writer) lifetime achievement award 2020 Click Here for High Quality Mock Test Series for IBPS RRB PO Mains 2020 Click Here for High Quality Mock Test Series for IBPS RRB Clerk Mains 2020 Follow us: Telegram , Facebook , Twitter , Instagram 1 Current Affairs Capsule for SBI/IBPS/RRB PO Mains Exam 2021 – Part 2 Rome's Fiumicino Airport First airport in the world to Skytrax (Leonardo -

Silver Spoon Oligarchs

CO-AUTHORS Chuck Collins is director of the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies where he coedits Inequality.org. He is author of the new book The Wealth Hoarders: How Billionaires Pay Millions to Hide Trillions. Joe Fitzgerald is a research associate with the IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good. Helen Flannery is director of research for the IPS Charity Reform Initiative, a project of the IPS Program on Inequality. She is co-author of a number of IPS reports including Gilded Giving 2020. Omar Ocampo is researcher at the IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good and co-author of a number of reports, including Billionaire Bonanza 2020. Sophia Paslaski is a researcher and communications specialist at the IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good. Kalena Thomhave is a researcher with the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors wish to thank Sarah Gertler for her cover design and graphics. Thanks to the Forbes Wealth Research Team, led by Kerry Dolan, for their foundational wealth research. And thanks to Jason Cluggish for using his programming skills to help us retrieve private foundation tax data from the IRS. THE INSTITUTE FOR POLICY STUDIES The Institute for Policy Studies (www.ips-dc.org) is a multi-issue research center that has been conducting path-breaking research on inequality for more than 20 years. The IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good was founded in 2006 to draw attention to the growing dangers of concentrated wealth and power, and to advocate policies and practices to reverse extreme inequalities in income, wealth, and opportunity. -

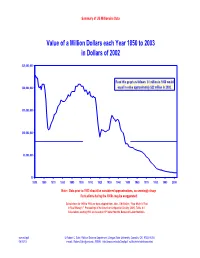

Summary of Millionaire Materials

Summary of US Millionaire Data Value of a Million Dollars each Year 1850 to 2003 in Dollars of 2002 $25,000,000 Read this graph as follows: $1 million in 1850 would $20,000,000 equal in value approximately $22 million in 2002. $15,000,000 $10,000,000 $5,000,000 $0 1850 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Note: Data prior to 1913 should be considered approximations, so seemingly sharp fluctuations during the 1800s may be exaggerated. Calculations for 1850 to 1912 use data adapted from John J. McCusker, "How Much Is That in Real Money?," Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society (2001), Table A-1. Calculations starting 1913 are based on CPI data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. summill.pdf © Robert C. Sahr, Political Science Department, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331-6206 06/10/03 e-mail: [email protected]; WWW: http://www.orst.edu/Dept/pol_sci/fac/sahr/sahrhome.html Summary of US Millionaire Data, page 2 Dollars Needed to Equal in Value $1 Million in the Year 2002 for each Year 1850 to 2003 $1,100,000 $1,000,000 $900,000 $800,000 $700,000 Read this graph as follows: To equal the $600,000 value of $1 million in dollars of the year 2002 would have required about $45,000 in 1850. $500,000 $400,000 $300,000 $200,000 $100,000 $0 1850 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Note: Data prior to 1913 should be considered approximations, so seemingly sharp fluctuations during the 1800s may be exaggerated. -

The Forbes 400 and the Gates-Buffett Giving Pledge

ACRN Journal of Finance and Risk Perspectives Vol. 4, Issue 1, February 2015, p. 82-101 ISSN 2305-7394 THE FORBES 400 AND THE GATES-BUFFETT GIVING PLEDGE 1 2 4 Kent Hickman , Mark Shrader , Danielle Xu3, Dan Lawson 1,2,3 School of Business Administration, Gonzaga University 4Department of Finance, Indiana University of Pennsylvania Abstract. Large disparities in the distribution of wealth across the world’s population may contribute to political and societal instability. While public policy decisions regarding taxes and transfer payments could lead to more equal wealth distribution, they are controversial. This paper examines a voluntary initiative aimed at wealth redistribution, the Giving Pledge, developed by Warren Buffet and Bill and Melinda Gates. High wealth individuals signing the pledge commit to give at least half of their wealth to charity either over their lifetime or in their will. We attempt to identify personal characteristics of America’s billionaires that influence their decision to sign the pledge. We find several factors that are related to the likelihood of giving, including the individual’s net worth, the source of their wealth, their level of education, their notoriety and their political affiliation. Keywords: Philanthropy, Giving Pledge, Forbes 400, wealth redistribution Introduction The Giving Pledge is an effort to help address society’s most pressing problems by inviting the world’s wealthiest individuals and families to commit to giving more than half of their wealth to philanthropy or charitable causes either during their lifetime or in their will. (The Giving Pledge, 2013). The extremely rich are known to purchase islands, yachts, sports teams and collect art in their pursuit of happiness. -

Billionaire Bonanza Reports in 2015 and 2017

CO-AUTHORS: Chuck Collins directs the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies, where he also co-edits Inequality.org. His most recent book is Is Inequality in America Irreversible? from Polity Press and in 2016 he published Born on Third Base. Other reports and books by Collins include Reversing Inequality: Unleashing the Transformative Potential of An More Equal Economy and 99 to 1: How Wealth Inequality is Wrecking the World and What We Can Do About It. His 2004 book Wealth and Our Commonwealth, written with Bill Gates Sr., makes the case for taxing inherited fortunes. Josh Hoxie directs the Project on Opportunity and Taxation at the Institute for Policy Studies and co- edits Inequality.org. He co-authored a number of reports on topics ranging from economic inequality, to the racial wealth divide, to philanthropy. Hoxie has written widely on income and wealth maldistribution for Inequality.org and other media outlets. He worked previously as a legislative aide for U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders. Acknowledgements: We received significant assistance in the production of this report. We would like to thank our colleagues at IPS who helped us throughout the report. The Institute for Policy Studies (www.IPS-dc.org) is a multi-issue research center founded in 1963. The Program on Inequality and the Common Good was founded in 2006 to draw attention to the growing dangers of concentrated wealth and power, and to advocate policies and practices to reverse extreme inequalities in income, wealth, and opportunity. The Inequality.org website (http://inequality.org/) provides an online portal into all things related to the income and wealth gaps that so divide us. -

Billionaire Bonanza, the Forbes 400 and the Rest of Us

billionaire bonanza report: the forbes 4...and the rest of us december 2015 chuck collins josh hoxie CO-AUTHORS: Chuck Collins is a senior scholar at the Institute for Policy Studies and directs the Institute’s Program on Inequality and the Common Good. An expert on U.S. inequality, Collins has authored several books, including 99 to 1: How Wealth Inequality is Wrecking the World and What We Can Do About It. His book Wealth and Our Commonwealth, written with Bill Gates Sr., makes the case for taxing inherited fortunes, and his The Moral Measure of the Economy, written with Mary Wright, explores Christian ethics and economic life. Collins co-founded the Patriotic Millionaires Josh Hoxie joined the Institute for Policy Studies in August 2014 and currently heads up the IPS Project on Opportunity and Taxation. He worked previously as a legislative aide for U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, both in his office in Washington, D.C. and in Burlington. Josh attained a BA in political science and economics from St. Michael’s College in Colchester, Vermont. He has written widely on income and wealth maldistribution for Inequality.org and other media outlets. Graphic Design: Eric VanDreason. Acknowledgements: We received significant assistance in the production of this report. We would like to thank our colleagues at IPS who helped us throughout the report-development process: Sarah Anderson, Sam Pizzigati, Bob Lord, John Cavanagh, and Elaine de Leon. A special thanks to IPS associate fellow Salvatore Babones at the University of Sydney for his help on quantitative calculations. We also received guidance from Tom Shapiro and Tatjana Meschede at the Institute on Assets on Social Policy and insights on quantitative methods from Kaiti Tuthill, Kevin Baier, and Melissa Sands. -

Seven Greek-Americans on Forbes' 400 Richest List

S O C V st ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ W ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ E 101 ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 The National Herald anniversa ry N www.thenationalherald.com A wEEkly GrEEk-AmEriCAN PuBliCATiON 1915-2016 VOL. 19, ISSUE 991 October 8-14 , 2016 c v $1.50 Maillis, a Seven Greek-Americans On Forbes’ 400 Richest List 9-Year-Old New Balance’s Jim Davis, a philanthropist Enrolled and son of Greek immigrants, is #94 Forbes Magazine’s annual list crosoft’s Bill Gates at number of the 400 richest Americans in - one and Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, in College cludes seven Greek-Americans, who moved into second place with New Balance running ahead of investor Warren Buffet, shoe’s Jim Davis leading his have fortunes totaling $814 bil - Budding Physicist peers at number 94 with an es - lion. timated fortune of $5.1 billion, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg Plans to Prove tied with seven others. is fourth, former New York Davis, 73, the son of Greek Mayor Michael Bloomberg, that God Exists immigrants, lives in Newton, sixth, and Larry Page and Sergey Massachusetts, and oversees Brin of Google at 9 and 10, with TNH Staff one of the top running shoe Brin the richest immigrant on companies in the world. the list, 14 of whom have more William Maillis is a 9-year- He has donated to many money than New York business - old with a lot more on his plate causes, including financing stat - man and Presidential candidate than most kids his age. Most are ues of 1946 Boston Marathon Donald Trump, whose fortune in the fourth grade, tackling winner Stylianos Kyriakides, fell $800 million very fast. -

Inside the 2016 Forbes 400: Facts and Figures About America's Richest People

Inside The 2016 Forbes 400: Facts And Figures About America's Richest People forbes.com/sites/kerryadolan/2016/10/04/inside-the-2016-forbes-400-facts-and-figures-about-americas-richest-people/print/ Kerry A. Dolan 10/3/2016 By Kerry A. Dolan and Luisa Kroll Soaring stock prices at the hottest tech firms shook up the top of The FORBES 400 this year. Amazon.com CEO Jeff Bezos gained $20 billion, more than anyone else in America. That was enough to boost his net worth to $67 billion, making him the second-richest person in the country, even wealthier than Warren Buffett, who finished in third place for the first time in 15 years. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, who is now worth $55.5 billion, moved into fourth place, his highest rank ever, while Oracle founder Larry Ellison fell to No. 5 for the first time since 2007. The country’s 400 richest are wealthier than ever, with a combined net worth of $2.4 trillion and an average net worth of $6 billion, both record highs. The minimum net worth for entry was $1.7 billion, the same as it was a year ago. A record 153 billionaires were too poor to make the exclusive club. Bill Gates is No. 1 for the 23rd year running, with a net worth of $81 billion. His stake in Microsoft, which he cofounded in 1975 and where he still serves as a board member, accounts for about 13% of his fortune. Gates also owns stakes in tractor maker Deere & Co., Canadian National Railway, car dealer AutoNation and many other companies.