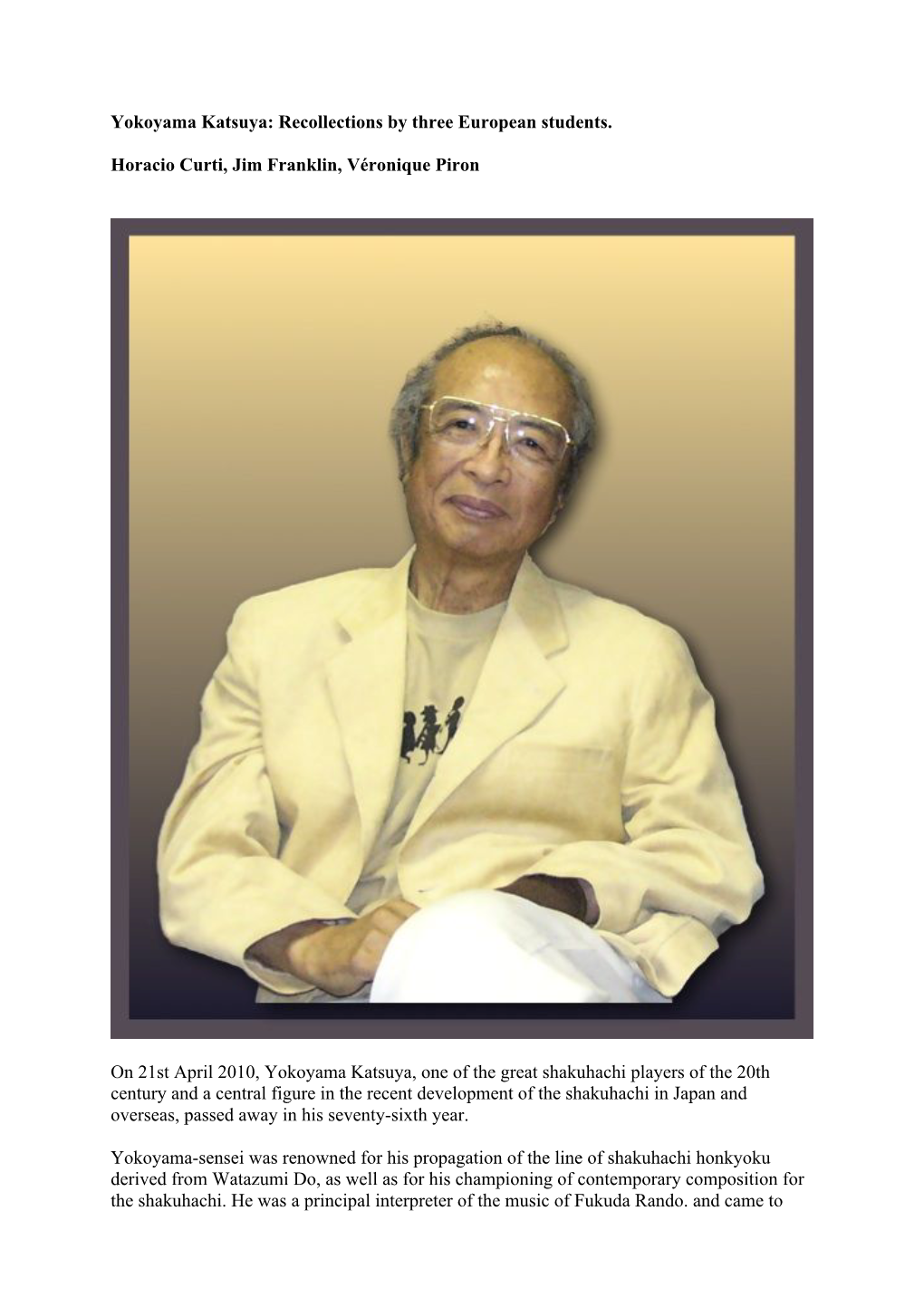

Yokoyama Katsuya: Recollections by Three European Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 89, 1969-1970

THE SOLOISTS KINSHI TSURUTA, born in Ebeotsu Asahi- kawa in the Hokkaido Prefecture, is a player of the traditional Japanese instru- ment, the biwa. In November 1961 she appeared on stage for the first time since World War II in a joint recital. On film she has been heard in the music of Takemitsu for Kwaidan. She and Katsuya Yokoyama created the music for a series of television dramas, Yoshitsune, broadcast by NHK. photo by Dick Loek Takemitsu wrote a new work for Kinshi Tsuruta and Mr Yokoyama called Eclipse, played at the Nissei Theater in May 1966. KATSUYA YOKOYAMA, a leading player of the shakuhachi, was born in Kohnuki Numazu, Shizuoka Prefecture. He is known for his interpretation of almost all the new music written for his instrument in Japan. He is also a member of 'Sanbonkai', a trio of Japanese instrumentalists. His playing has been heard in the film scores by Take- mitsu for Seppuku and Kwaidan as well as in the television series Yoshitsune. His tra- SM^^^^M^^^^*. JJ. photo by Dick Loek ditional instrument is a bamboo flute, and his technique has been inherited from his teacher, Watazumi. Both Kinshi Tsuruta and Katsuya Yokoyama have taken part in the recording of November steps no. 1 with the Toronto Symphony, conducted by Seiji Ozawa, for RCA. EVELYN MANDAC, born in the Philippines, took her degree in music at the University of the Philippines. She then studied for several years at Oberlin College and the Juilliard School of Music. Last season she appeared with the Orchestras of Honolulu and Phoenix, with the Oratorio Society of New York and the Dallas and San Antonio Symphonies. -

Issue 15 ESS Newsletter 2010 02.Pdf

1 Index Letter from the editor Philip Horan 3 European Shakuhachi Festival 2010 Marek Matvija 4 The Swiss Shakuhachi Society Madeleine Zeller 6 The Shakuhachi in Germany Albert G. Helm 9 Shin-Tozan Ryû France Jean-François Lagrost 11 La Voie du Bambou Daniel Lifermann 13 The Shakuhachi in Italy Fiore De Mattia 15 The Shakuhachi in Ireland Philip Horan 17 The Kyotaku Tradition in Europe Hans van Loon 18 Playing Shakuhachi in the Netherlands Joke Verdoold 20 The Shakuhachi in Spain Jose Vargas- Zuñiga 22 The Shakuhachi in Sweden/Finland Niklas Natt och Dag 24 The Shakuhachi Scene in the UK Kiku Day/Michael Coxall 26 The Shakuhachi in Denmark Kiku Day 31 Membership page 34 Cover-work by Dominique Houlet [email protected] What I could say is when I was 20, I spent some time in India with a wonderfull side-blown flute made of madake bamboo. I had great experiences playing for people. I met my actual teacher/master in a temple after a memorable improvisation. I’m still translating his speeches into French today. My job is in the graphic arts, as I was a prolific artist when a teenager. I create websites, logos, illustrations and lay-outs for communication as an independant designer. I discovered synthesizers some time ago, computers from their begining and digital arts/photography. I plunged into macro photos of flowers and realised a concert/show with a film made of flower pictures, called “Listening to the Flowers” where I played shakuhachi live. So I choose to learn shakuhachi for the occasion, and had around 6 months to get ready for the concert. -

Celebrating Beate Sirota Gordon

Asia Society and Japan Society present Celebrating Beate Sirota Gordon Photo by Mark Stern Sunday, April 28, 2013 5:00 pm Followed by a reception Asia Society 725 Park Avenue New York, NY Program Welcome Rachel Cooper Director, Global Performing Arts and Special Cultural Initiatives, Asia Society Performance Yoko Takebe Gilbert Violinist, New York Philharmonic J.S. Bach, Adagio from a Sonata for Unaccompanied Violin Video “I am Beate Gordon” Video Tribute Honorable Sonia Sotomayor Associate Justice, United States Supreme Court Remarks Robert Oxnam Vishakha N. Desai Presidents Emeriti, Asia Society Remarks Honorable Shigeyuki Hiroki Ambassador and Consul General of Japan in New York Video Tribute SamulNori “ssit-gim gut” Kim Duk-soo, Korean traditional percussion master, and his troupe members perform a shaman ceremony to guide the departed’s soul to heaven and console those who are left behind. Remarks Honorable Motoatsu Sakurai President, Japan Society Former Ambassador and Consul General of Japan in New York Kathak Dance Parul Shah “Radha-Naval” Radha-Naval is based on the 'nritya' of Kathak, the narrative elements of dance, and involves 'abhinaya', facial expressions and gestures. Remarks Honorable Carolyn B. Maloney U.S. Representative, 12th Congressional District, New York Video Tribute Yoko Ono Artist Remarks Dick Cavett Television host Video Tribute Robert Wilson Theater artist Performance Margaret Leng Tan Lee Hye Kyung, “Dream Play” (2000, revised 2011) Raphael Mostel, “Star-Spangled Etude No. 3” (“Furling Banner,” 1996) Video Tribute Yoshito Ohno Dancer Remarks Richard Lanier President of the Board of Trustees, Asian Cultural Council Performance Eiko & Koma “Duet” Remarks Theodore Levin Arthur R. -

Works Commissioned by Or Written for the New York Philharmonic (Including the New York Symphony Society)

Works Commissioned by or Written for the New York Philharmonic (Including the New York Symphony Society). Updated: August 31, 2011 Date Composer Work Conductor Soloists Premiere Funding Source Notes Nov. 14, 1925 Taylor, Symphonic Poem, “Jurgen” W. Damrosch World Commissioned by Damrosch for the Deems Premiere Symphony Society Dec 3, 1925 Gershwin Concerto for Piano in F W. Damrosch George Gershwin World Commissioned by Damrosch for the Premiere Symphony Society Dec 26, 1926 Sibelius Symphonic Poem Tapiola , W. Damrosch World Commisioned by The Symphony Op. 112 Premiere Society Feb 12, 1928 Holst Tone Poem Egdon Heath W. Damrosch World Commissioned by the Symphony Premiere Society Dec 20, 1936 James Overture, Bret Harte Barbirolli World American Composers Award Premiere Nov 4, 1937 Read Symphony No. 1 Barbirolli World American Composers Award Premiere Apr 2, 1938 Porter Symphony No. 1 Porter World American Composers Award Premiere Dec 18, 1938 Haubiel Passacaglia in A minor Haubiel World American Composers Award Premiere Jan 19, 1939 Van Vactor Symphony in D Van Vactor World American Composers Award Premiere Feb 26, 1939 Sanders Little Symphony in G Sanders World American Composers Award Premiere Jan 24, 1946 Stravinsky Symphony in Three Stravinsky World Movements Premiere Nov 16, 1948 Gould Philharmonic Waltzes Mitropoulos World Premiere Jan 14, 1960 Schuller Spectra Mitropoulos World In honor of Dimitri Mitropoulos Premiere Sep 23, 1962 Copland Connotations for Orchestra Bernstein World Celebrating the opening season of Premiere Philharmonic -

Sacred Abjection in Zen Shakuhachi Published on Ethnomusicology Review (

Sacred Abjection in Zen Shakuhachi Published on Ethnomusicology Review (https://ethnomusicologyreview.ucla.edu) Sacred Abjection in Zen Shakuhachi Zachary Wallmark In a manuscript from the 1820s, Japanese shakuhachi player Hisamatsu Fuyo proclaims it is “despicable, if someone loves to produce a splendid tone” on the instrument (an end-blown bamboo flute) (Gutzwiller 1984:61).1 This strongly worded condemnation expresses an often overlooked aesthetic—and ethical—orientation within the shakuhachi tradition, one still active among certain practitioners: to play beautifully is something loathsome, expressive not just of poor musical judgment, but of bad character. “Splendid tone” is a mark, indeed, of the abject.2 As formulated by literary theorist Julia Kristeva (1982), abjection is a virulent species of exclusion and division, a strategy for demarcating the bounded self in relationship to the exterior, dangerous other. Kristeva puts it succinctly when she defines the abject as that which is “opposed to I” (1).3 In this terse formulation, the abject is not simply a neutral counterpart to the subject; it is radically, unforgivably separate. By definition, then, abjection relies on a strictly policed binary logic founded on the fundamental duality between “I” and “not-I.” This basic division spawns still other dualities tinged with the dynamics of abjection, including good and bad, clean and dirty, and beautiful and ugly. These conceptual distinctions, so key to the workings of culture, also play a major role in the creation, consumption, and evaluation of music. Because music is one of the most powerful means of symbolically ordering reality, this should come as no surprise: the binary essence of abjection maps onto music in diverse and fascinating ways, expressing itself in a range of culturally- and historically-specific manifestations. -

Messiaen Turangalila Symphony / November Steps Mp3, Flac, Wma

Messiaen Turangalila Symphony / November Steps mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Turangalila Symphony / November Steps Country: France Style: Contemporary MP3 version RAR size: 1595 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1128 mb WMA version RAR size: 1256 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 256 Other Formats: VQF VOX DTS MOD AC3 MP3 MP2 Tracklist Hide Credits –Olivier Turangalîla Messiaen Symphony A1 – Introduction 6:30 A2 – Chant D'Amour 1 8:12 A3 – Turangalîla 1 5:05 B1 – Chant D'Amour 2 11:10 B2 – Joie Du Sang Des Étoiles 6:18 B3 – Jardin Du Sommeil D'Amour 11:40 C1 – Turangalîla 2 3:57 C2 – Développement De L'Amout 11:20 C3 – Turangalîla 3 4:33 C4 – Finale 7:00 November Steps D –Toru Takemitsu Biwa – Kinshi TsurutaComposed By – Toru 20:23 TakemitsuShakuhachi – Katsuya Yokoyama Credits Composed By – Olivier Messiaen (tracks: A1 to C4) Conductor – Seiji Ozawa Engineer [Recording] – Bernard Keville Liner Notes – Olivier Messiaen, Toru Takemitsu Ondes Martenot – Jeanne Loriod (tracks: A1 to C4) Orchestra – Toronto Symphony* Photography By – Dick Loek Piano – Yvonne Loriod (tracks: A1 to C4) Producer – Peter Dellheim Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: B.I.E.M Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Olivier Messiaen / Toru Olivier Messiaen / Takemitsu - Seiji Ozawa, RCA Toru Takemitsu - Toronto Symphony* - Victor LSC-7051 LSC-7051 US 1968 Seiji Ozawa, Turangalîla Symphony / Red Toronto Symphony* November Steps (2xLP, Seal Gat) Olivier Messiaen / Toru Olivier Messiaen / Takemitsu - Seiji Ozawa, -

022510 EE Program Notes

ENSEMBLE EAST Thursday, February 25, 2010 8:00 p.m. About the Music SUE NO CHIGIRI ("Vow of Eternal Love") Matsuura Kengyô (d.1822) Koto part by Yaezaki Kengyô (d. 1848) or Urazaki Kengyô This piece is written in the traditional three-part tegotomono form (two vocal sections flank an elaborate and often lengthy instrumental interlude). However, instead of dividing one poem into two parts, the first and last vocal sections in this case consist of two separate but related poems. The title comes from the last line. Both poems concern the torments and uncertainties of love. In the first, the lover feels lost and unsure, and the lonely cry of the stork along the windy shore is used to symbolize her agitated state of mind; in the second, the lover, though separated from her beloved, fervently hopes that he will remain faithful to their vow, if not for the sake of this life, then for the next. The Japanese traditionally believed that true love could be strong enough to last through three incarnations, so that the separated lovers, if they remained true, might meet again in the next life. MAEUTA (Opening Song) The white-capped waves rush headlong by, knowing nothing of my misery, or do they...? I spy some seaweed, symbol of love in the old poems, yet my love for you brings no joy! It's as if I were in a small fishing boat [the fishing boat symbolizes the lover whose life is governed by the whims of the sea, itself a symbol of destiny], rocking in the surf near the shore.. -

Fuchigami Rafaelhirochi M.Pdf

RAFAEL HIROCHI FUCHIGAMI ASPECTOS CULTURAIS E MUSICOLÓGICOS DO SHAKUHACHI NO BRASIL Campinas 2014 II UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS INSTITUTO DE ARTES RAFAEL HIROCHI FUCHIGAMI ASPECTOS CULTURAIS E MUSICOLÓGICOS DO SHAKUHACHI NO BRASIL Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Música do Instituto de Artes da Universidade Estadual de Campinas para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Música, na Área de Concentração: Fundamentos Teóricos. Orientador: EDUARDO AUGUSTO OSTERGREN Este exemplar corresponde à versão final da Dissertação defendida pelo aluno Rafael Hirochi Fuchigami, e orientada pelo Prof. Dr. Eduardo Augusto Ostergren. Campinas 2014 III IV Instituto de Artes Comissão de Pós-Graduação Defesa de Dissertação de Mestrado em Música, apresentada pelo mestrando Rafael Hirochi Fuchigami – RA 08 2552 – como parte dos requisitos para a obtenção do título de Mestre, perante a Banca Examinadora: V VI Dedico o presente trabalho à minha amada família e àqueles que sopram este bambu ao longo das gerações. VII VIII Agradecimentos Àqueles que sempre estiveram comigo, ensinando-me sobre a vida e apoiando-me irrestritamente, minha família Yochio, Lourdes, Hélio e minha amiga Mônica. Ao orientador Eduardo Ostergren, à UNICAMP, à FAPESP que nos concedeu a bolsa de estudos, à FAEPEX e ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Música do Instituto de Artes, que apoiou a participação em eventos, congressos e trabalho de campo. À professora Alice Satomi, que ofereceu apoio e sugeriu o título desta dissertação. Aos meus professores de shakuhachi Sugawara Sensei e Kakizakai Sensei, pelo apoio, incentivo e pelo aprendizado durante as aulas no Japão. Ao Yamaoka Sensei, Douglas Okura e Henrique Elias; a Matheus Ferreira e aos amigos do Suizen Dōjō, pela colaboração. -

Glories of the Japanese Music Heritage ANCIENT SOUNDSCAPES REBORN Japanese Sacred Gagaku Court Music and Secular Art Music

The Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies ~ Japanese Cultural Heritage Initiatives ~ and the Columbia Music Performance Program present Our 9th Season Concert Glories of the Japanese Music Heritage ANCIENT SOUNDSCAPES REBORN Japanese Sacred Gagaku Court Music and Secular Art Music featuring renowned Japanese Gagaku musicians and New York-based Hōgaku artists with the Columbia Gagaku and Hōgaku Instrumental Ensembles of New York and newly commissioned works Sunday March 30, 2014 at 4:00PM Miller Theatre, Columbia University (116th Street & Broadway) 2 PROGRAM OUTLINE PART I: SACRED GAGAKU AND CLASSICAL SECULAR COURT MUSIC Hyōjō no netori (Prelude Mode Centering on the note of E) Etenraku (Music of the Divine Heavens) Kashin (Glorious Days) Sōjō no netori (Prelude Mode Centering on the note of G) Konju no ha (Ah! Cheers) Hyōjō no chōshi (Prelude Mode Centering on the note of E) Kanshū (The Tune from Kanshū That Vitiates Vipers) ***** Intermission (10 minutes) ***** PART II: EARLY MODERN WINDS AND STRINGS (HŌGAKU) MEDITATIVE ZEN MUSIC FOR SHAKUHACHI & KOTO SALON MUSIC Kyorei (Bell of Emptiness) Tadao Sawai, Datura (The Datura Flower) Tadao Sawai, Jōgen no kyoku (The Waxing Moon) ***** Intermission (10 minutes) ***** PART III: CONTEMPORARY MUSIC FOR JAPANESE HERITAGE INSTRUMENTS & COMPUTER Brad Garton, … desu.(2014) for shō, koto, biwa and computer (new commission) Akira Takaoka, Five Movements on Modulations (2014) for shō, hichiriki, ryūteki and computer (new commission) * Full details from p. 8 3 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY MUSIC PERFORMANCE PROGRAM The Music Performance Program (MPP) of Columbia University seeks to enable students to develop as musicians within the academic setting of Columbia, by providing and facilitating opportunities for musical instruction, participation, and performance. -

Issue 23 ESS Newsletter FEB 2013.Pdf

1 Index Letter from the chairperson 3 Letter from Kakizakai Kaoru 4 Barcelona 2013 (English) 5 Barcelona 2013 (Spanish) 8 Barcelona 2013 (French) 11 Barcelona 2013 (German) 15 Barcelona 2013 (Russian) 19 Barcelona 2013 (Italian) 23 Prague Shakuhachi Festival 2013: New horizons by Marek Matvija 26 Performances by Rodrigo Rodriguez 29 News from Europe 32 Master class with Teruo Furuya 34 Master class de Teruo Furuya (French) 36 Kyoto San 38 Kurahashi Workshop 40 La Voie du Bambou, France 41 Performances by Viz Michael Kremietz 44 Hélène Codjo in the Netherlands 45 News from around the world 46 A Trip to London Marek Matvija 48 CD releases with Kiku Day 51 Two Rivers by Adrian Freedman & Ravi 52 CD Review by Gunnar Jinmei Linder 54 CD Release by Jose Vargas 57 Membership of the European Shakuhachi Society 58 Mitgliedschaft in der European Shakuhachi Society 59 Adhésion à la Fédération Européenne du Shakuhachi 60 Letter from the editor, Welcome to the February 2013 ESS newsletter. This edition contains informaion about many events in the coming months as well as details of summer schools. It is also great to get more notices and reviews of new CDs. Many thanks to the translators who make our newsletter and organisation more inclusive. In many cases, I have presented the information in the format presented to me, so please forgive any inconsistencies. I include some News from around the World that is sent to the ESS. However, I must state that is outside the scope the ESS to feature all world events that come to our attention. -

Glories of the Japanese Traditional Music Heritage “Winds and Strings of Change”

In Partnership with Carnegie Hall JapanNYC Festival Seiji Ozawa, Artistic Director The Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies is honored to present Concert I: Glories of the Japanese Traditional Music Heritage “Winds and Strings of Change” Featuring the master artists Yukio Tanaka – biwa Kifū Mitsuhashi - shakuhachi Yōko Nishi - koto James Nyoraku Schlefer— shakuhachi A concert of traditional and innovative works honoring the memory of Tōru Takemitsu (1930-1996) one of Japan’s greatest composers whose works have transformed the soundscapes of the 20th-century Thursday, December 16, 2010 at 6:00 PM Miller Theatre, Columbia University (116th Street & Broadway) Tōru Takemitsu (1930-1996) Columbia University Honorary Doctorate Recipient, 1996 Tōru Takemitsu is one of the most extraordinary world-class composers of music to emerge in our post world war era. His music speaks across all cultures and is loved and admired both by musicians and non- musicians alike. His long career of creating, and being commissioned to write, major works for orchestras, chamber groups and all manner of individual performers throughout Europe and America, to say nothing of Japan and Asia, has led to his being awarded the 1994 Grawemeyer Award, known as the “Nobel Prize” for music. Takemitsu’s music navigates powerful traditional Japanese and modern Western musical forces toward what he believes to be a common global future for classical music. A profound “philosopher of music” as well, he has written seminal and highly influential essays about his creative process, his understanding of “sound” in human life, and his hopes for the future of world music. ~Quoted from the original Columbia University Honorary Doctorate designation~ 3 Tōru Takemitsu Tōru Takemitsu’s first encounter with Western music was as a boy during the war when a mentor secretly played for him records of French chansons. -

Japanese Traditional Instrumental Music an Overview of Solo and Ensemble Development

Japanese Traditional Instrumental Music An overview of solo and ensemble development Bruno Deschênes http://www.mustrad.org.uk/articles/japan.htm Introduction Although Japan is obviously the most Westernized country in all of Asia, Japanese people are known as being great guardians of tradition. When it comes to music and all other forms of art, traditions are firmly and safely preserved, yet, as in all Asian countries, there is a decline; the youth being more interested in pop and rock music then their own traditions. Modernization is surely a threat; but the sense of tradition in Japan is so strong that their traditional music will continue to thrive and, to a small extent, with the help of the West. Japanese music is extremely diverse: solo music, chamber music, court music, festival and folk music, different types of theatre music, percussion music, epic singing, and many more. This article presents a general overview of Japanese traditional solo and how it evolved into ensemble music. I will start with describing the most important principles in Japanese aesthetic, principles which are used in all forms of art. It will be followed by a section on the traditional teaching of music. I will then move on to music itself; its historical beginnings, its evolution into solo music and then into ensemble music. The conclusion will briefly present today's situation. I also include a list of suggested CDs for those who want to investigate further into Japanese music. Aesthetics Traditional Japanese music is basically meditative in character. Its performance is highly ritualized, as much in the music itself, as in the composure of the musicians when performing it.