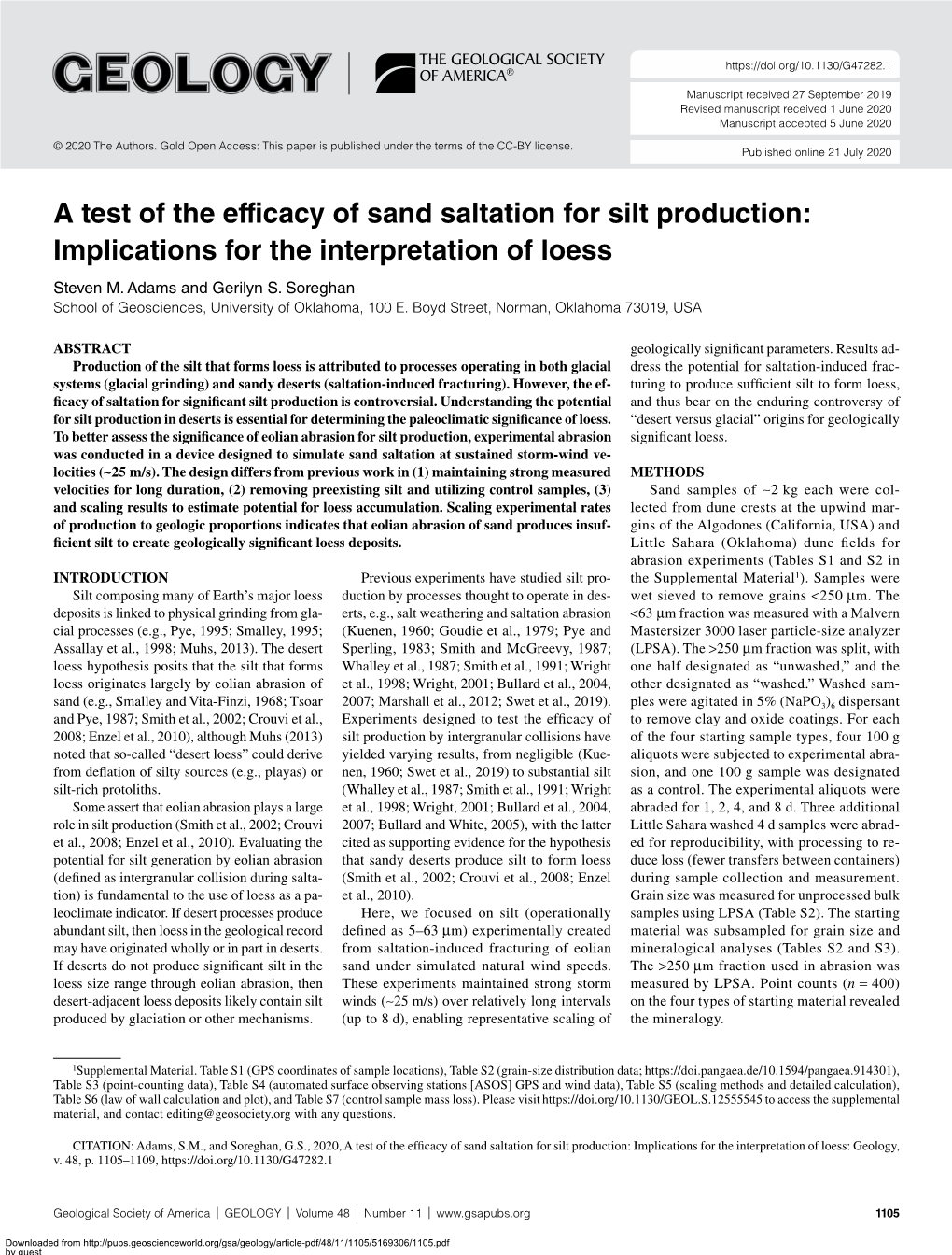

A Test of the Efficacy of Sand Saltation for Silt Production: Implications for the Interpretation of Loess Steven M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Measurement of Bedload Transport in Sand-Bed Rivers: a Look at Two Indirect Sampling Methods

Published online in 2010 as part of U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2010-5091. Measurement of Bedload Transport in Sand-Bed Rivers: A Look at Two Indirect Sampling Methods Robert R. Holmes, Jr. U.S. Geological Survey, Rolla, Missouri, United States. Abstract Sand-bed rivers present unique challenges to accurate measurement of the bedload transport rate using the traditional direct sampling methods of direct traps (for example the Helley-Smith bedload sampler). The two major issues are: 1) over sampling of sand transport caused by “mining” of sand due to the flow disturbance induced by the presence of the sampler and 2) clogging of the mesh bag with sand particles reducing the hydraulic efficiency of the sampler. Indirect measurement methods hold promise in that unlike direct methods, no transport-altering flow disturbance near the bed occurs. The bedform velocimetry method utilizes a measure of the bedform geometry and the speed of bedform translation to estimate the bedload transport through mass balance. The bedform velocimetry method is readily applied for the estimation of bedload transport in large sand-bed rivers so long as prominent bedforms are present and the streamflow discharge is steady for long enough to provide sufficient bedform translation between the successive bathymetric data sets. Bedform velocimetry in small sand- bed rivers is often problematic due to rapid variation within the hydrograph. The bottom-track bias feature of the acoustic Doppler current profiler (ADCP) has been utilized to accurately estimate the virtual velocities of sand-bed rivers. Coupling measurement of the virtual velocity with an accurate determination of the active depth of the streambed sediment movement is another method to measure bedload transport, which will be termed the “virtual velocity” method. -

Sedimentation and Shoaling Work Unit

1 SEDIMENTARY PROCESSES lAND ENVIRONMENTS IIN THE COLUMBIA RIVER ESTUARY l_~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~7 I .a-.. .(.;,, . I _e .- :.;. .. =*I Final Report on the Sedimentation and Shoaling Work Unit of the Columbia River Estuary Data Development Program SEDIMENTARY PROCESSES AND ENVIRONMENTS IN THE COLUMBIA RIVER ESTUARY Contractor: School of Oceanography University of Washington Seattle, Washington 98195 Principal Investigator: Dr. Joe S. Creager School of Oceanography, WB-10 University of Washington Seattle, Washington 98195 (206) 543-5099 June 1984 I I I I Authors Christopher R. Sherwood I Joe S. Creager Edward H. Roy I Guy Gelfenbaum I Thomas Dempsey I I I I I I I - I I I I I I~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ PREFACE The Columbia River Estuary Data Development Program This document is one of a set of publications and other materials produced by the Columbia River Estuary Data Development Program (CREDDP). CREDDP has two purposes: to increase understanding of the ecology of the Columbia River Estuary and to provide information useful in making land and water use decisions. The program was initiated by local governments and citizens who saw a need for a better information base for use in managing natural resources and in planning for development. In response to these concerns, the Governors of the states of Oregon and Washington requested in 1974 that the Pacific Northwest River Basins Commission (PNRBC) undertake an interdisciplinary ecological study of the estuary. At approximately the same time, local governments and port districts formed the Columbia River Estuary Study Taskforce (CREST) to develop a regional management plan for the estuary. PNRBC produced a Plan of Study for a six-year, $6.2 million program which was authorized by the U.S. -

A Study of Unstable Slopes in Permafrost Areas: Alaskan Case Studies Used As a Training Tool

A Study of Unstable Slopes in Permafrost Areas: Alaskan Case Studies Used as a Training Tool Item Type Report Authors Darrow, Margaret M.; Huang, Scott L.; Obermiller, Kyle Publisher Alaska University Transportation Center Download date 26/09/2021 04:55:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/7546 A Study of Unstable Slopes in Permafrost Areas: Alaskan Case Studies Used as a Training Tool Final Report December 2011 Prepared by PI: Margaret M. Darrow, Ph.D. Co-PI: Scott L. Huang, Ph.D. Co-author: Kyle Obermiller Institute of Northern Engineering for Alaska University Transportation Center REPORT CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 REVIEW OF UNSTABLE SOIL SLOPES IN PERMAFROST AREAS ............................... 1 3.0 THE NELCHINA SLIDE ..................................................................................................... 2 4.0 THE RICH113 SLIDE ......................................................................................................... 5 5.0 THE CHITINA DUMP SLIDE .............................................................................................. 6 6.0 SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 9 7.0 REFERENCES ................................................................................................................. 10 i A STUDY OF UNSTABLE SLOPES IN PERMAFROST AREAS 1.0 INTRODUCTION -

The Distribution of Silty Soils in the Grayling Fingers Region of Michigan: Evidence for Loess Deposition Onto Frozen Ground

Geomorphology 102 (2008) 287–296 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Geomorphology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/geomorph The distribution of silty soils in the Grayling Fingers region of Michigan: Evidence for loess deposition onto frozen ground Randall J. Schaetzl ⁎ Department of Geography, 128 Geography Building, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, 48824-1117, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: This paper presents textural, geochemical, mineralogical, soils, and geomorphic data on the sediments of the Received 12 September 2007 Grayling Fingers region of northern Lower Michigan. The Fingers are mainly comprised of glaciofluvial Received in revised form 25 March 2008 sediment, capped by sandy till. The focus of this research is a thin silty cap that overlies the till and outwash; Accepted 26 March 2008 data presented here suggest that it is local-source loess, derived from the Port Huron outwash plain and its Available online 10 April 2008 down-river extension, the Mainstee River valley. The silt is geochemically and texturally unlike the glacial fl Keywords: sediments that underlie it and is located only on the attest parts of the Finger uplands and in the bottoms of Glacial geomorphology upland, dry kettles. On sloping sites, the silty cap is absent. The silt was probably deposited on the Fingers Loess during the Port Huron meltwater event; a loess deposit roughly 90 km down the Manistee River valley has a Permafrost comparable origin. Data suggest that the loess was only able to persist on upland surfaces that were either Kettles closed depressions (currently, dry kettles) or flat because of erosion during and after loess deposition. -

Sand Dunes Computer Animations and Paper Models by Tau Rho Alpha*, John P

Go Home U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Sand Dunes Computer animations and paper models By Tau Rho Alpha*, John P. Galloway*, and Scott W. Starratt* Open-file Report 98-131-A - This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this program has been used by the U.S. Geological Survey, no warranty, expressed or implied, is made by the USGS as to the accuracy and functioning of the program and related program material, nor shall the fact of distribution constitute any such warranty, and no responsibility is assumed by the USGS in connection therewith. * U.S. Geological Survey Menlo Park, CA 94025 Comments encouraged tralpha @ omega? .wr.usgs .gov [email protected] [email protected] (gobackward) <j (goforward) Description of Report This report illustrates, through computer animations and paper models, why sand dunes can develop different forms. By studying the animations and the paper models, students will better understand the evolution of sand dunes, Included in the paper and diskette versions of this report are templates for making a paper models, instructions for there assembly, and a discussion of development of different forms of sand dunes. In addition, the diskette version includes animations of how different sand dunes develop. Many people provided help and encouragement in the development of this HyperCard stack, particularly David M. Rubin, Maura Hogan and Sue Priest. -

Bed-Load Transport Equation for Sheet Flow

TECHNICAL NOTES Bed-Load Transport Equation for Sheet Flow Athol D. Abrahams1 Abstract: When open-channel flows become sufficiently powerful, the mode of bed-load transport changes from saltation to sheet flow. Where there is no suspended sediment, sheet flow consists of a layer of colliding grains whose basal concentration approaches that of the stationary bed. These collisions give rise to a dispersive stress that acts normal to the bed and supports the bed load. An equation for predicting the rate of bed-load transport in sheet flow is developed from an analysis of 55 flume and closed conduit experiments. The ϭ ϭ ϭ ϭ ϭ ␣ϭ equation is ib where ib immersed bed-load transport rate; and flow power. That ib implies that eb tan ub /u, where eb ϭ ϭ ␣ϭ Bagnold’s bed-load transport efficiency; ub mean grain velocity in the sheet-flow layer; and tan dynamic internal friction coeffi- ␣Ϸ Ϸ Ϸ cient. Given that tan 0.6 for natural sand, ub 0.6u, and eb 0.6. This finding is confirmed by an independent analysis of the experimental data. The value of 0.60 for eb is much larger than the value of 0.12 calculated by Bagnold, indicating that sheet flow is a much more efficient mode of bed-load transport than previously thought. DOI: 10.1061/͑ASCE͒0733-9429͑2003͒129:2͑159͒ CE Database keywords: Sediment transport; Bed loads; Geomorphology. Introduction transport process. In contrast, the bed-load transport equation pro- When open-channel flows transporting noncohesive sediments posed here is extremely simple and entirely empirical. -

Chapter 14. Streams and Floods

Physical Geology, First University of Saskatchewan Edition is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 International License Read this book online at http://openpress.usask.ca/physicalgeology/ Chapter 14. Streams and Floods Adapted by Joyce M. McBeth, University of Saskatchewan from Physical Geology by Steven Earle Learning Objectives After carefully reading this chapter, completing the exercises within it, and answering the questions at the end, you should be able to: • Explain the hydrological cycle, its relevance to streams, and describe the residence time of water in these systems • Describe what a drainage basin is, and explain the origins of the different types of drainage patterns • Explain how streams become graded, and how certain geological and anthropogenic changes can result in a stream becoming ungraded • Describe the formation of stream terraces • Describe the processes that move sediments in streams, and how changes in stream velocity affect the types of sediments that are moved by the stream • Explain the origin of natural stream levees • Describe the process of stream evolution and the types of environments where one would expect to find straight-channel, braided, and meandering streams • Describe the annual flow characteristics of typical streams in Canada and the processes that lead to flooding • Describe some of the important historical floods in Canada • Determine the probability of floods of various magnitudes, based on the flood history of a stream • Explain some of the steps that we can take to limit damage from flooding Why Study Streams? Figure 14.1 A small waterfall on Johnston Creek in Johnston Canyon, Banff National Park, AB Source: Steven Earle (2015) CC BY 4.0 view source https://opentextbc.ca/geology/ Chapter 14. -

Classifying Rivers - Three Stages of River Development

Classifying Rivers - Three Stages of River Development River Characteristics - Sediment Transport - River Velocity - Terminology The illustrations below represent the 3 general classifications into which rivers are placed according to specific characteristics. These categories are: Youthful, Mature and Old Age. A Rejuvenated River, one with a gradient that is raised by the earth's movement, can be an old age river that returns to a Youthful State, and which repeats the cycle of stages once again. A brief overview of each stage of river development begins after the images. A list of pertinent vocabulary appears at the bottom of this document. You may wish to consult it so that you will be aware of terminology used in the descriptive text that follows. Characteristics found in the 3 Stages of River Development: L. Immoor 2006 Geoteach.com 1 Youthful River: Perhaps the most dynamic of all rivers is a Youthful River. Rafters seeking an exciting ride will surely gravitate towards a young river for their recreational thrills. Characteristically youthful rivers are found at higher elevations, in mountainous areas, where the slope of the land is steeper. Water that flows over such a landscape will flow very fast. Youthful rivers can be a tributary of a larger and older river, hundreds of miles away and, in fact, they may be close to the headwaters (the beginning) of that larger river. Upon observation of a Youthful River, here is what one might see: 1. The river flowing down a steep gradient (slope). 2. The channel is deeper than it is wide and V-shaped due to downcutting rather than lateral (side-to-side) erosion. -

Types of Landslides.Indd

Landslide Types and Processes andslides in the United States occur in all 50 States. The primary regions of landslide occurrence and potential are the coastal and mountainous areas of California, Oregon, Land Washington, the States comprising the intermountain west, and the mountainous and hilly regions of the Eastern United States. Alaska and Hawaii also experience all types of landslides. Landslides in the United States cause approximately $3.5 billion (year 2001 dollars) in dam- age, and kill between 25 and 50 people annually. Casualties in the United States are primar- ily caused by rockfalls, rock slides, and debris flows. Worldwide, landslides occur and cause thousands of casualties and billions in monetary losses annually. The information in this publication provides an introductory primer on understanding basic scientific facts about landslides—the different types of landslides, how they are initiated, and some basic information about how they can begin to be managed as a hazard. TYPES OF LANDSLIDES porate additional variables, such as the rate of movement and the water, air, or ice content of The term “landslide” describes a wide variety the landslide material. of processes that result in the downward and outward movement of slope-forming materials Although landslides are primarily associ- including rock, soil, artificial fill, or a com- ated with mountainous regions, they can bination of these. The materials may move also occur in areas of generally low relief. In by falling, toppling, sliding, spreading, or low-relief areas, landslides occur as cut-and- La Conchita, coastal area of southern Califor- flowing. Figure 1 shows a graphic illustration fill failures (roadway and building excava- nia. -

River Processes- Erosion, Transportation and Deposition Task 1: for Each of the Processes of Erosion and Transportation Draw a Diagram Show the Process at Work

River Processes- Erosion, Transportation and Deposition Task 1: For each of the processes of erosion and transportation draw a diagram show the process at work In the upper course of the main process is Erosion. This is where the bed and banks of the river are worn away. A river can erode in one of four ways: Process Definition Diagram Hydraulic the sheer force of water hitting the action banks of the river: Abrasion fine material rubs against the riverbank The bank is worn away by a sand- papering action called abrasion, and collapses. This occurs on the outside of meanders. Attrition material is moved along the bed of a river, collides with other material, and breaks up into smaller pieces. Corrosion rocks forming the banks and bed of a river are dissolved by acids in the water. Once the material is eroded it can then be transported by one of four ways, which will depend upon the energy of the river: Process Definition Diagram Traction large rocks and boulders are rolled along the bed of the river. Saltation smaller stones are bounced along the bed of the river Suspension fine material which is carried by the water and which gives the river its 'muddy' colour. Solution dissolved material transported by the river. In the middle and lower course, the land is much flatter, this means that the river is flowing more slowly and has much less energy. The river starts to deposit (drop) the material that it has been carry Deposition Challenge: Add labels onto the diagram to show where all of the processes could be happening in the river channel. -

Gabion Retaining Walls with Alternate Fill Materials

Gabion Retaining Walls with Alternate Fill Materials IGC 2009, Guntur, INDIA GABION RETAINING WALLS WITH ALTERNATE FILL MATERIALS K.S. Beena Reader, School of Engineering, Cochin University of Science and Technology, Cochin–682022, India. E-mail: [email protected] P.K. Jayasree Lecturer in Civil Engineering, College of Engineering, Trivandrum–695 016, India. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Although gabions have been used from ancient times, it is only in the last few decades that their wide spread use has lead them to become an accepted construction material in Civil Engineering. Gabion retaining walls are mass gravity structure made up of strong mesh containers known as gabion boxes, filled with quarry stone. Considering the cost and scarcity of quarry stones, the replacement of it with some other cheaper material will make the construction more economical. This aspect is studied here. Considering the specific gravity, friction, cost and availability, quarry dust and red soil was selected as the fill material. Model gabion retaining walls were constructed for the purpose in which, different combinations of quarry dust, red soil and coarse aggregate were taken as the filling material. Analyzing the lateral deformations of various cases, it can be concluded that a 50%–50% combination of alternative material and aggregate will perform better than the coarse aggregate alone, considering the cost of construction. 1. INTRODUCTION dry stone gravity mass wall made of gabion boxes. They are cost effective, environmental friendly and durable structures. Retaining walls, one of the major geotechnical applications, Because of these reasons gabions are widely used now days are mainly used in the case of highways and railways to all over the world. -

Sediment Bed-Load Transport: a Standardized Notation

geosciences Article Sediment Bed-Load Transport: A Standardized Notation Ulrich Zanke 1,2,* and Aron Roland 3 1 TU, Darmstadt, Inst. für Wasserbau und Hydraulik, 64287 Darmstadt, Germany 2 Z & P—Prof. Zanke & Partner, Ackerstr. 21, D-30826 Garbsen-Hannover, Germany 3 CEO BGS-ITE, Pfungstaedter Straße 20, D-64297 Darmstadt, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 7 August 2020; Accepted: 1 September 2020; Published: 16 September 2020 Abstract: Morphodynamic processes on Earth are a result of sediment displacements by the flow of water or the action of wind. An essential part of sediment transport takes place with permanent or intermittent contact with the bed. In the past, numerous approaches for bed-load transport rates have been developed, based on various fundamental ideas. For the user, the question arises which transport function to choose and why just that one. Different transport approaches can be compared based on measured transport rates. However, this method has the disadvantage that any measured data contains inaccuracies that correlate in different ways with the transport functions under comparison. Unequal conditions also exist if the factors of transport functions under test are fitted to parts of the test data set during the development of the function, but others are not. Therefore, a structural formula comparison is made by transferring altogether 13 transport functions into a standardized notation. Although these formulas were developed from different perspectives and with different approaches, it is shown that these approaches lead to essentially the same basic formula for the main variables. These are shear stress and critical shear stress.