Sedimentation and Shoaling Work Unit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Measurement of Bedload Transport in Sand-Bed Rivers: a Look at Two Indirect Sampling Methods

Published online in 2010 as part of U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2010-5091. Measurement of Bedload Transport in Sand-Bed Rivers: A Look at Two Indirect Sampling Methods Robert R. Holmes, Jr. U.S. Geological Survey, Rolla, Missouri, United States. Abstract Sand-bed rivers present unique challenges to accurate measurement of the bedload transport rate using the traditional direct sampling methods of direct traps (for example the Helley-Smith bedload sampler). The two major issues are: 1) over sampling of sand transport caused by “mining” of sand due to the flow disturbance induced by the presence of the sampler and 2) clogging of the mesh bag with sand particles reducing the hydraulic efficiency of the sampler. Indirect measurement methods hold promise in that unlike direct methods, no transport-altering flow disturbance near the bed occurs. The bedform velocimetry method utilizes a measure of the bedform geometry and the speed of bedform translation to estimate the bedload transport through mass balance. The bedform velocimetry method is readily applied for the estimation of bedload transport in large sand-bed rivers so long as prominent bedforms are present and the streamflow discharge is steady for long enough to provide sufficient bedform translation between the successive bathymetric data sets. Bedform velocimetry in small sand- bed rivers is often problematic due to rapid variation within the hydrograph. The bottom-track bias feature of the acoustic Doppler current profiler (ADCP) has been utilized to accurately estimate the virtual velocities of sand-bed rivers. Coupling measurement of the virtual velocity with an accurate determination of the active depth of the streambed sediment movement is another method to measure bedload transport, which will be termed the “virtual velocity” method. -

Geomorphic Classification of Rivers

9.36 Geomorphic Classification of Rivers JM Buffington, U.S. Forest Service, Boise, ID, USA DR Montgomery, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA Published by Elsevier Inc. 9.36.1 Introduction 730 9.36.2 Purpose of Classification 730 9.36.3 Types of Channel Classification 731 9.36.3.1 Stream Order 731 9.36.3.2 Process Domains 732 9.36.3.3 Channel Pattern 732 9.36.3.4 Channel–Floodplain Interactions 735 9.36.3.5 Bed Material and Mobility 737 9.36.3.6 Channel Units 739 9.36.3.7 Hierarchical Classifications 739 9.36.3.8 Statistical Classifications 745 9.36.4 Use and Compatibility of Channel Classifications 745 9.36.5 The Rise and Fall of Classifications: Why Are Some Channel Classifications More Used Than Others? 747 9.36.6 Future Needs and Directions 753 9.36.6.1 Standardization and Sample Size 753 9.36.6.2 Remote Sensing 754 9.36.7 Conclusion 755 Acknowledgements 756 References 756 Appendix 762 9.36.1 Introduction 9.36.2 Purpose of Classification Over the last several decades, environmental legislation and a A basic tenet in geomorphology is that ‘form implies process.’As growing awareness of historical human disturbance to rivers such, numerous geomorphic classifications have been de- worldwide (Schumm, 1977; Collins et al., 2003; Surian and veloped for landscapes (Davis, 1899), hillslopes (Varnes, 1958), Rinaldi, 2003; Nilsson et al., 2005; Chin, 2006; Walter and and rivers (Section 9.36.3). The form–process paradigm is a Merritts, 2008) have fostered unprecedented collaboration potentially powerful tool for conducting quantitative geo- among scientists, land managers, and stakeholders to better morphic investigations. -

Bed-Load Transport Equation for Sheet Flow

TECHNICAL NOTES Bed-Load Transport Equation for Sheet Flow Athol D. Abrahams1 Abstract: When open-channel flows become sufficiently powerful, the mode of bed-load transport changes from saltation to sheet flow. Where there is no suspended sediment, sheet flow consists of a layer of colliding grains whose basal concentration approaches that of the stationary bed. These collisions give rise to a dispersive stress that acts normal to the bed and supports the bed load. An equation for predicting the rate of bed-load transport in sheet flow is developed from an analysis of 55 flume and closed conduit experiments. The ϭ ϭ ϭ ϭ ϭ ␣ϭ equation is ib where ib immersed bed-load transport rate; and flow power. That ib implies that eb tan ub /u, where eb ϭ ϭ ␣ϭ Bagnold’s bed-load transport efficiency; ub mean grain velocity in the sheet-flow layer; and tan dynamic internal friction coeffi- ␣Ϸ Ϸ Ϸ cient. Given that tan 0.6 for natural sand, ub 0.6u, and eb 0.6. This finding is confirmed by an independent analysis of the experimental data. The value of 0.60 for eb is much larger than the value of 0.12 calculated by Bagnold, indicating that sheet flow is a much more efficient mode of bed-load transport than previously thought. DOI: 10.1061/͑ASCE͒0733-9429͑2003͒129:2͑159͒ CE Database keywords: Sediment transport; Bed loads; Geomorphology. Introduction transport process. In contrast, the bed-load transport equation pro- When open-channel flows transporting noncohesive sediments posed here is extremely simple and entirely empirical. -

Chapter 14. Streams and Floods

Physical Geology, First University of Saskatchewan Edition is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 International License Read this book online at http://openpress.usask.ca/physicalgeology/ Chapter 14. Streams and Floods Adapted by Joyce M. McBeth, University of Saskatchewan from Physical Geology by Steven Earle Learning Objectives After carefully reading this chapter, completing the exercises within it, and answering the questions at the end, you should be able to: • Explain the hydrological cycle, its relevance to streams, and describe the residence time of water in these systems • Describe what a drainage basin is, and explain the origins of the different types of drainage patterns • Explain how streams become graded, and how certain geological and anthropogenic changes can result in a stream becoming ungraded • Describe the formation of stream terraces • Describe the processes that move sediments in streams, and how changes in stream velocity affect the types of sediments that are moved by the stream • Explain the origin of natural stream levees • Describe the process of stream evolution and the types of environments where one would expect to find straight-channel, braided, and meandering streams • Describe the annual flow characteristics of typical streams in Canada and the processes that lead to flooding • Describe some of the important historical floods in Canada • Determine the probability of floods of various magnitudes, based on the flood history of a stream • Explain some of the steps that we can take to limit damage from flooding Why Study Streams? Figure 14.1 A small waterfall on Johnston Creek in Johnston Canyon, Banff National Park, AB Source: Steven Earle (2015) CC BY 4.0 view source https://opentextbc.ca/geology/ Chapter 14. -

Classifying Rivers - Three Stages of River Development

Classifying Rivers - Three Stages of River Development River Characteristics - Sediment Transport - River Velocity - Terminology The illustrations below represent the 3 general classifications into which rivers are placed according to specific characteristics. These categories are: Youthful, Mature and Old Age. A Rejuvenated River, one with a gradient that is raised by the earth's movement, can be an old age river that returns to a Youthful State, and which repeats the cycle of stages once again. A brief overview of each stage of river development begins after the images. A list of pertinent vocabulary appears at the bottom of this document. You may wish to consult it so that you will be aware of terminology used in the descriptive text that follows. Characteristics found in the 3 Stages of River Development: L. Immoor 2006 Geoteach.com 1 Youthful River: Perhaps the most dynamic of all rivers is a Youthful River. Rafters seeking an exciting ride will surely gravitate towards a young river for their recreational thrills. Characteristically youthful rivers are found at higher elevations, in mountainous areas, where the slope of the land is steeper. Water that flows over such a landscape will flow very fast. Youthful rivers can be a tributary of a larger and older river, hundreds of miles away and, in fact, they may be close to the headwaters (the beginning) of that larger river. Upon observation of a Youthful River, here is what one might see: 1. The river flowing down a steep gradient (slope). 2. The channel is deeper than it is wide and V-shaped due to downcutting rather than lateral (side-to-side) erosion. -

River Processes- Erosion, Transportation and Deposition Task 1: for Each of the Processes of Erosion and Transportation Draw a Diagram Show the Process at Work

River Processes- Erosion, Transportation and Deposition Task 1: For each of the processes of erosion and transportation draw a diagram show the process at work In the upper course of the main process is Erosion. This is where the bed and banks of the river are worn away. A river can erode in one of four ways: Process Definition Diagram Hydraulic the sheer force of water hitting the action banks of the river: Abrasion fine material rubs against the riverbank The bank is worn away by a sand- papering action called abrasion, and collapses. This occurs on the outside of meanders. Attrition material is moved along the bed of a river, collides with other material, and breaks up into smaller pieces. Corrosion rocks forming the banks and bed of a river are dissolved by acids in the water. Once the material is eroded it can then be transported by one of four ways, which will depend upon the energy of the river: Process Definition Diagram Traction large rocks and boulders are rolled along the bed of the river. Saltation smaller stones are bounced along the bed of the river Suspension fine material which is carried by the water and which gives the river its 'muddy' colour. Solution dissolved material transported by the river. In the middle and lower course, the land is much flatter, this means that the river is flowing more slowly and has much less energy. The river starts to deposit (drop) the material that it has been carry Deposition Challenge: Add labels onto the diagram to show where all of the processes could be happening in the river channel. -

Sediment Bed-Load Transport: a Standardized Notation

geosciences Article Sediment Bed-Load Transport: A Standardized Notation Ulrich Zanke 1,2,* and Aron Roland 3 1 TU, Darmstadt, Inst. für Wasserbau und Hydraulik, 64287 Darmstadt, Germany 2 Z & P—Prof. Zanke & Partner, Ackerstr. 21, D-30826 Garbsen-Hannover, Germany 3 CEO BGS-ITE, Pfungstaedter Straße 20, D-64297 Darmstadt, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 7 August 2020; Accepted: 1 September 2020; Published: 16 September 2020 Abstract: Morphodynamic processes on Earth are a result of sediment displacements by the flow of water or the action of wind. An essential part of sediment transport takes place with permanent or intermittent contact with the bed. In the past, numerous approaches for bed-load transport rates have been developed, based on various fundamental ideas. For the user, the question arises which transport function to choose and why just that one. Different transport approaches can be compared based on measured transport rates. However, this method has the disadvantage that any measured data contains inaccuracies that correlate in different ways with the transport functions under comparison. Unequal conditions also exist if the factors of transport functions under test are fitted to parts of the test data set during the development of the function, but others are not. Therefore, a structural formula comparison is made by transferring altogether 13 transport functions into a standardized notation. Although these formulas were developed from different perspectives and with different approaches, it is shown that these approaches lead to essentially the same basic formula for the main variables. These are shear stress and critical shear stress. -

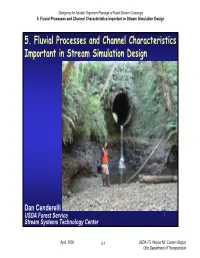

5. Fluvial Processes and Channel Characteristics Important in Stream Simulation Design

Designing for Aquatic Organism Passage at Road-Stream Crossings 5. Fluvial Processes and Channel Characteristics Important in Stream Simulation Design 5. Fluvial Processes and Channel Characteristics Important in Stream Simulation Design Dan Cenderelli USDA Forest Service 1 Stream Systems Technology Center April 2009 5-1 USDA-FS: Wayne NF, Eastern Region Ohio Department of Transportation Designing for Aquatic Organism Passage at Road-Stream Crossings 5. Fluvial Processes and Channel Characteristics Important in Stream Simulation Design Acknowledgements Traci Sylte, P.E. Bob Gubernick, P.E. Hydrologist, Engineering Geologist, Lolo NF, Montana Tongass NF, Alaska 2 April 2009 5-2 USDA-FS: Wayne NF, Eastern Region Ohio Department of Transportation Designing for Aquatic Organism Passage at Road-Stream Crossings 5. Fluvial Processes and Channel Characteristics Important in Stream Simulation Design Presentation Outline • Watershed Context • Discharge and Channel Characteristics • Channel Characteristics and Fluvial Processes • Channel slope • Channel shape, confinement, entrenchment • Channel planform • Channel slope, shape, and planform • Channel-bed material • Channel bedforms • Channel Classifications • Understanding and Predicting Channel Adjustments/Responses 3 April 2009 5-3 USDA-FS: Wayne NF, Eastern Region Ohio Department of Transportation Designing for Aquatic Organism Passage at Road-Stream Crossings 5. Fluvial Processes and Channel Characteristics Important in Stream Simulation Design Feb 2003 Presentation Objectives • A better understanding and appreciation of channel features, fluvial processes, and channel dynamics at a Culvert Characteristics road-stream crossing. • built in late 1950’s • diameter 1.83 m • length 27 m • gradient 2.1 percent June 2007 • Understand the importance of integrating fluvial geomorphology with engineering principles to design a road-stream crossing that contains a Replacement Culvert Characteristics •Bottomless Structure natural and dynamic channel •Span: 5.49 m; Height: 2.25 m through the structure. -

Multiple Working Hypotheses at Perseverance Valley: Fracture and Aeolian Abrasion

49th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2018 (LPI Contrib. No. 2083) 2516.pdf MULTIPLE WORKING HYPOTHESES AT PERSEVERANCE VALLEY: FRACTURE AND AEOLIAN ABRASION. R. Sullivan1, M. Golombek2, K. Herkenhoff3, and the Athena Science Team, 1CCAPS, Cornell Uni- versity, Ithaca, NY 14853 ([email protected]), 2Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, CA, 3USGS, Flagstaff, AZ. Introduction: Understanding the role of water in At Meridiani Planum, aeolian abrasion is recognized past Martian environments is the overarching goal of the when a rock surface is exposed to a dominant sand-driv- Mars Exploration Rover (MER) mission. To this end, ing wind direction and includes components of con- the rover Opportunity has been exploring the vicinity of trasting hardness, so that positive relief "rock tails" or Perseverance Valley, a system of troughs extending 190 stalks in weaker material extend downwind, protected m down the steep (~15°) interior rim of 22 km diameter behind more resistant materials as the rock surface Endeavour crater. From orbit, Perseverance Valley is erodes. Rocks with more uniform hardness can develop an array of shallow, interleaved troughs reminiscent of classic ventifact shapes, as well as textures such as elon- anastomosing fluvial systems on Earth. However, no gation of surface pits. The aeolian abrasion and reduc- basal deposits are apparent subjacent to the trough sys- tion of ejecta blocks at relatively recent impact sites tem, indicating either post-depositional erosion of ma- across the Meridiani plains indicates aeolian abrasion terials carried through the troughs, or the trough system has effectively reduced surface relief at Meridiani never functioned as a conduit for fluid-borne materials. -

Chapter 10 Movement of Sediment by Water Flows

CHAPTER 10 MOVEMENT OF SEDIMENT BY WATER FLOWS INTRODUCTION 1 A simple flume experiment on sediment movement by a unidirectional current of water in a flume serves to introduce the material in this chapter. Place a layer of sediment in the flume, level it to have a planar surface, and establish a uniform flow at a certain depth and velocity. Gradually, in steps, increase the strength of the flow beyond the condition for incipient movement. The magnitude of the flow strength relative to what is required for incipient movement of the bed sediment is conventionally called the flow intensity, and is usually taken to be the ratio τo/τoc (or, what is the same, u*/u*c), where the subscript c denotes the threshold (“critical”) condition. 2 At first the particles move as bed load, by hopping, rolling, and/or sliding. Particle movement is neither continuous nor uniform over the bed: brief gusts or pulses of movement affect groups of particles locally, and seemingly randomly, on the bed. Particles move a short distance, stop, and then move again. Even when they are moving, they are generally not moving as fast as the fluid near the bed surface. 3 As the flow becomes stronger, some of the particles moving near the bed are lifted upward by upward-moving turbulent eddies and travel for more or less long distances downstream as suspended load. The stronger the flow and/or the finer the sediment, the greater is the concentration of suspended sediment, the higher it can travel in the flow, and the longer it moves downstream before returning to the bed. -

A Phenomenological Study of Sediment Transport in Shallow Overland Flow

A PHENOMENOLOGICAL STUDY OF SEDIMENT TRANSPORT IN SHALLOW OVERLAND FLOW M. J. M. Römkens, S. M. Rao, S. N. Prasad ABSTRACT. Soil erosion is a highly complicated phenomenon consisting of many component processes. On upland areas, these processes are usually thought of as detachment and transport of soil particles by rainfall and surface flow. One of the most difficult processes to quantify is sediment transport. This process depends on a host of factors including sediment type, size, size distribution, and concentrations on one hand and the flow regime relative to rates and velocities on the oth- er hand. The effect of all of these factors is influenced by soil surface cover and surface roughness conditions. The Na- tional Sedimentation Laboratory has in recent years conducted a series of basic laboratory studies to better understand sediment movement in shallow overland flow. These experiments involved super-critical flow regimes in a 7 m long and 10 cm wide channel in which sand-size material was seeded at the upstream end at controlled rates in a super-critical flow regime with Froude numbers >1. Particle sizes were coarse sand (1000 to 1400 μm), medium sand (600 to 850 μm), and spherical glass beads (600 to 1000 μm). Measurements included particle velocity and particle concentrations using pho- tonic probes. Three modes of transport were noted: a saltation mode at low concentrations, sediment waves in which sed- iment moved in regularly spaced waves, and a meander mode. The latter two modes were attributed to particle interac- tions. The transported sediment was continuously collected at the downstream end by a rotating sampler. -

Some Characteristics of Fluvial Processes in Rivers

Some Characteristics of Fluvial Processes in Rivers William W. Emmet t*. Luna B. Leopold** and Robert M. Myrick*** Abstract Fluvial processes in rivers have been studied extensively in the United States during the past 20 years. This paper relates some older studies of scour and fill to some new studies for which detailed data on water-surface slopes and bedload-transport rates help to substantiate earlier interpretations. Although discussion is based on data from three small rivers, the principles involved have transfer value to other rivers. Reversal in maximum values of water-surface slope from riffles during low flow to pools during high flow causes a similar reversal in maximum values of stream power; this reversal is reflected in measured values of bedload-transport rate. Both pool and riffle reaches are likely to contribute sediment to bedload, resulting in generalized scour during high flow. However, spatially-variable bedload-transport rates require those reaches with the least available stream power during times of high transport rate to temporarily fill as continuity in the sediment budget is maintained. Similarly, those reaches with the least available stream power during times of receding river stage become sinks for storage of the moving sediment. This process helps explain the sorting mechanism of sediment and the maintenance of pool-riffle sequences in rivers. The volume of scoured material within its annual travel distance is, on average, equal to annual bedload. but this is only an approximation because all bed particles do not move at the same speed or travel the same distance. Scour is associated with dilation of the grain bed through the scour depth, but individual particles move intermittently and at a speed much less than that of the water.