Approximately 286 Reasons Why You Should Listen to Jesse Winchester

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inventory of Presidential Gifts at NARA (Ie, Gifts from Foreign Nations An

Description of document: National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) inventory of Presidential Gifts at NARA (i.e., gifts from foreign nations and others to Presidents that were transferred to NARA by law and stored by NARA, 2016 Requested date: 15-August-2017 Released date: 18-September-2017 Posted date: 11-June-2018 Note: Material released appears to only be part of the complete inventory. See note on page 578. Source of document: FOIA Request National Archives and Records Administration General Counsel 8601 Adelphi Road, Room 3110 College Park, MD 20740-6001 Fax: 301-837-0293 Email: [email protected] The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

1Guitar PDF Songs Index

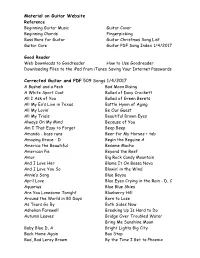

Material on Guitar Website Reference Beginning Guitar Music Guitar Cover Beginning Chords Fingerpicking Bass Runs for Guitar Guitar Christmas Song List Guitar Care Guitar PDF Song Index 1/4/2017 Good Reader Web Downloads to Goodreader How to Use Goodreader Downloading Files to the iPad from iTunes Saving Your Internet Passwords Corrected Guitar and PDF 509 Songs 1/4/2017 A Bushel and a Peck Bad Moon Rising A White Sport Coat Ballad of Davy Crockett All I Ask of You Ballad of Green Berets All My Ex’s Live in Texas Battle Hymn of Aging All My Lovin’ Be Our Guest All My Trials Beautiful Brown Eyes Always On My Mind Because of You Am I That Easy to Forget Beep Beep Amanda - bass runs Beer for My Horses + tab Amazing Grace - D Begin the Beguine A America the Beautiful Besame Mucho American Pie Beyond the Reef Amor Big Rock Candy Mountain And I Love Her Blame It On Bossa Nova And I Love You So Blowin’ in the Wind Annie’s Song Blue Bayou April Love Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain - D, C Aquarius Blue Blue Skies Are You Lonesome Tonight Blueberry Hill Around the World in 80 Days Born to Lose As Tears Go By Both Sides Now Ashokan Farewell Breaking Up Is Hard to Do Autumn Leaves Bridge Over Troubled Water Bring Me Sunshine Moon Baby Blue D, A Bright Lights Big City Back Home Again Bus Stop Bad, Bad Leroy Brown By the Time I Get to Phoenix Bye Bye Love Dream A Little Dream of Me Edelweiss Cab Driver Eight Days A Week Can’t Help Falling El Condor Pasa + tab Can’t Smile Without You Elvira D, C, A Careless Love Enjoy Yourself Charade Eres Tu Chinese Happy -

Singer-Songwriter Jesse Winchester Here Friday

Singer-songwriter Jesse Winchester here Friday BY GEORGE VARGA SEPTEMBER 8, 2010 JESSE WINCHESTER Not many musicians can simultaneously make Elvis Costello choke up and bring Neko Case to tears with an unadorned solo acoustic performance of a single song. But that’s exactly what veteran troubadour Jesse Winchester did last fall in New York when he sang his wonderfully poignant ballad about two teenagers in love, “Sham-A-Ling-Dong-Ding,” a standout number from his enchanting 2009 album, “Love Filling Station.” You can watch it here: http:/www.youtube.com/watch?v=5uKGWpqnS8E%20 The setting was Harlem’s famed Apollo Theater, where Costello’s Sundance TV music series, “Spectacle,” filmed its first two seasons in front of loudly appreciative audiences. Louisiana native Winchester — who appeared on an episode alongside Costello, Case, Sheryl Crow and Ron Sexsmith — quietly stole the show with that song and an equally spare but stunning version of “The Brand New Tennessee Waltz,” an understated classic from his 1970 debut album. “Doing ‘Spectacle’ has been a big boost for my career,” said Winchester, who kicks off a five- city California tour here Friday night at the all-ages AMSD Concerts (formerly Acoustic Music San Diego) in Normal Heights. “I’m working at least twice as much as I used to. But I’m not really well known, so ‘twice as much’ for me is still not the same as for a really popular act.” In 2007, Winchester received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Society of Composers, Artists and Publishers. That he is not a household name stems from a simple twist of fate. -

Has Recorded Over 80 Albums and Has Received Seven Gold Records and Three Grammy Awards in His Storied Career

has recorded over 80 albums and has received seven gold records and three Grammy Awards in his storied career. In the mid 60’s, Lewis was the nation’s most successful jazz pianist, topping the charts with "The 'In' Crowd" and "Hang On Sloopy". Both singles each sold over one million copies, and were awarded gold discs. Now Ramsey is revisiting these classic records with a very special night. The 'In' Crowd “The In Crowd” provided Ramsey Lewis with his biggest hit reaching the top position on 1. The 'In' Crowd (Billy Page) - 5:50 the Billboard R&B Chart and No. 2 on their 2. Since I Fell for You (Buddy Johnson) - 4:06 top 200 albums chart in 1965 and the single, 3. Tennessee Waltz (Pee Wee King, Redd Stewart) - 5:02 4. You Been Talkin' 'Bout Me Baby “The ‘In’ Crowd” reaching No. 2 on the R&B (Gale Garnett, Ray Rivers) - 3:01 Chart and No. 5 on the Hot 100 singles chart 5. Spartacus (Love Theme from) (Alex North) - 7:17 in the same year. The album also received 6. Felicidade (Happiness) (Antônio Carlos Jobim, a Grammy Award in 1966 for Best Instru- Vinicius de Moraes) - 3:29 mental Jazz Performance by an Individual 7. Come Sunday (Duke Ellington) - 4:50 or Group and the single was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame Award in 2009. Hang On Ramsey! 1. A Hard Day's Night (John Lennon, Paul McCartney) - 4:56 “Hang On Ramsey!” reached No. 4 on the 2. All My Love Belongs to You (Sol Winkler, R&B charts and No. -

Travels of a Country Woman

Travels of a Country Woman By Lera Knox Travels of a Country Woman Travels of a Country Woman By Lera Knox Edited by Margaret Knox Morgan and Carol Knox Ball Newfound Press THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE LIBRARIES, KNOXVILLE iii Travels of a Country Woman © 2007 by Newfound Press, University of Tennessee Libraries All rights reserved. Newfound Press is a digital imprint of the University of Tennessee Libraries. Its publications are available for non-commercial and educational uses, such as research, teaching and private study. The author has licensed the work under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/>. For all other uses, contact: Newfound Press University of Tennessee Libraries 1015 Volunteer Boulevard Knoxville, TN 37996-1000 www.newfoundpress.utk.edu ISBN-13: 978-0-9797292-1-8 ISBN-10: 0-9797292-1-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2007934867 Knox, Lera, 1896- Travels of a country woman / by Lera Knox ; edited by Margaret Knox Morgan and Carol Knox Ball. xiv, 558 p. : ill ; 23 cm. 1. Knox, Lera, 1896- —Travel—Anecdotes. 2. Women journalists— Tennessee, Middle—Travel—Anecdotes. 3. Farmers’ spouses—Tennessee, Middle—Travel—Anecdotes. I. Morgan, Margaret Knox. II. Ball, Carol Knox. III. Title. PN4874 .K624 A25 2007 Book design by Martha Rudolph iv Dedicated to the Grandchildren Carol, Nancy, Susy, John Jr. v vi Contents Preface . ix A Note from the Newfound Press . xiii part I: The Chicago World’s Fair. 1 part II: Westward, Ho! . 89 part III: Country Woman Goes to Europe . -

Music Preferences of Geriatric Clients Within Three Sub-Populations Janelle Sikora

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2013 Music Preferences of Geriatric Clients within Three Sub-Populations Janelle Sikora Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MUSIC PREFERENCES OF GERIATRIC CLIENTS WITHIN THREE SUB-POPULATIONS By JANELLE SIKORA A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2013 Janelle Sikora defended this thesis on July 15, 2013. The members of the supervisory committee were: Kimberly VanWeelden Professor Directing Thesis Jayne Standley Committee Member Dianne Gregory Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii I dedicate this to my loving parents, Victor and Pat Sikora, who have supported me throughout college. They are generous, kind, and always there for me. They are my rock. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Kimberly VanWeelden for her guidance, support, and motivation throughout this process. Dr. VanWeelden’s research is what inspired me to conduct this study and I am grateful to have been fortunate enough to work with her. I thank Dr. Jayne Standley and Professor Dianne Gregory for being on my committee, educating me, and preparing me to be a professional. I thank both Dr. Farbman and Cindy Smith from AMTA for their help and taking the time to locate contacts for this study. -

BOBBY CHARLES LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie Van Varik

BOBBY CHARLES LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie van Varik. Bobby Charles was born Robert Charles Guidry on 21st February 1938 in Abbeville, Louisiana. A native Cajun himself, he recalled that his life “changed for ever” when he re-tuned his parents’ radio set from a local Cajun station to one playing records by Fats Domino. Most successful as a songwriter, he is regarded as one of the founding fathers of swamp pop. His own vocal style was laidback and drawling. His biggest successes were songs other artists covered, such as ‘See You Later Alligator’ by Bill Haley & His Comets; ‘Walking To New Orleans’ by Fats Domino - with whom he recorded a duet of the same song in the 1990s - and ‘(I Don’t Know Why) But I Do’ by Clarence “Frogman” Henry. It allowed him to live off the song-writing royalties for the rest of his life! No albums were by him released in this period. Two other well-known compositions are ‘The Jealous Kind’, recorded by Joe Cocker, and ‘Tennessee Blues’ by Kris. Disenchanted with the music business, Bobby disappeared from the music scene in the mid-1960s but returned in 1972 with a self-titled album on the Bearsville label on which he was accompanied by Rick Danko and several other members of the Band and Dr John. Bobby later made a rare live appearance as a guest singer on stage at The Last Waltz, the 1976 farewell concert of the Band, although his contribution was cut from Martin Scorsese’s film of the event. Bobby Charles returned to the studio in later years, recording a European-only album called Clean Water in 1987. -

November 1976 by Andy Childs “The Next Number Is by a Songwriter Who

November 1976 By Andy Childs “The next number is by a songwriter who we really like … his name’s Jesse Winchester.” (A liberal smattering of applause). “Great … you like him too!” That was Paul Bailey of the late lamented Chilli Willi & The Red Hot Peppers introducing “Midnight Bus” at the Zigzag Fifth Anniversary concert at the Roundhouse one Sunday afternoon in May 1974. Judging by the enthusiastic response which that introduction received, I would have thought that Jesse Winchester’s music would be pretty close to the hearts of a lot of Zigzaggers, but even if nobody who reads the rag nowadays went to that concert, how come the man Winchester didn’t figure at all in either ‘Favorite Lyricists’ or ‘Artiste You’d Most Like To See Featured in Zigzag’ polls recently conducted by Mag? Eh? What’s the matter with you all … been brainwashed by all this punk-rock tripe or something? Don’t you realise that Jesse Winchester is one of the very best songwriters you’ll ever have the privilege of hearing? Whether you give a monkey’s toss or not, I must report that it was my very great honour to meet and interview Jesse Winchester when he made an all-too-brief visit to this country earlier in the year; I also went to see him perform at Dingwalls in London, but due to a high percentage of obnoxious people and various other factors beyond mine or Winchester’s control, I derived precious little enjoyment from the evening. However, my respect and admiration for the man is still considerable, especially now that his immaculate fourth album ‘LET THE ROUGH SIDE DRAG’ is available for the delight of one and all. -

For Immediate Release Legendary Artists Gather in Tribute to Songwriter Jesse Winchester the Album, “Quiet About It: a Tribut

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE LEGENDARY ARTISTS GATHER IN TRIBUTE TO SONGWRITER JESSE WINCHESTER THE ALBUM, “QUIET ABOUT IT: A TRIBUTE TO JESSE WINCHESTER” A GIFT FROM GRATEFUL MUSICIANS & SONGWRITERS TO A MASTER AVAILABLE NOW EXCLUSIVELY ON iTunes Aug 14, 2012 – ‘‘Quiet About It: A Tribute To Jesse Winchester’ is now available on iTunes and will make its way to the other digital retailers September 3. The physical album will be available for purchase from the Mailboat Records Store (www.mailboatstore.com) September 25, 2012. The album features contributions from James Taylor, Rosanne Cash, Jimmy Bufett, Allen Toussaint, Vince Gill, Mac McAnally, Lyle Lovett, Lucinda Williams, Rodney Crowell, Little Feat and Elvis Costello. Jesse Winchester, a gifted songwriter and musician, has inspired many iconic artists of our time. When Jesse was diagnosed with esophageal cancer last year, Jimmy Bufett and Elvis Costello immediately agreed it would be a good idea to put together a tribute album as a show of support. As taken from the album liner notes, written by Bill Flanagan: “I don't know anyone who dislikes Jesse Winchester's music. It seems to me that there are only those who love it and those who have never heard it. Jesse is a songwriter's songwriter, praised by every composer from Dylan down and covered by greats from Wilson Pickett to the Everly Brothers. Jesse Winchester's songs are like mirrors in which both performers and listeners can see themselves. At Christmas of 2011 Bufett wrote to Jesse and told him the album was coming, a gift from a whole bunch of grateful musicians and songwriters to a master. -

Bradley Bledsoe, Emma Fiandt

winchester Page 1 of 12 Jesse Winchester, Bradley Bledsoe, Emma Fiandt [00:00:00] Bradley Bledsoe: On behalf of crossroads to freedom and Rhodes College, I would like to thank you for taking the time to share your story with us today. I’m Bradley Bledsoe, a senior at Rhodes College. Emma Fiandt: And I’m Emma Fiandt, a junior at Rhodes College. Bradley Bledsoe: And we are honored to meet you and learn from your inspirational story. Today’s interview will be archived online at the crossroads to freedom website. Emma Fiandt: Okay, let’s get started with some basic biographical information. Can you state your name please? Jesse Winchester: My real name, or legal name, is James Redue Winchester. Jesse, I usually go by Jesse. Emma Fiandt: And if you don’t mind telling us, what year were you born? Jesse Winchester: What year? 1944. Emma Fiandt: And where were you born and raised? Jesse Winchester: I was born in Shreveport, Louisiana, and I was raised – except for the first 12 years of my life in Mississippi, I was raised in Memphis. Emma Fiandt: Can you tell me a little bit about – [00:01:00] the neighborhood that you grew up in here in Memphis? Jesse Winchester: Well, I – kind of all over the place, but we would up in Germantown, and Germantown in those days was a very small farming town. It wasn’t anything like it is now. And that’s where I grew up, I guess. Emma Fiandt: What was it like growing up in Germantown? Jesse Winchester: It was great. -

Everly Brothers Collaborations Discography

CHRONOLOGY (APROX) OF DON & PHIL EVERLY'S COLLABORATIONS - 1954 TO DATE THIS LIST DOES NOT INCLUDE 'COVERS' BY OTHER ARTISTS OF TRACKS PREVIOUSLY RELEASED BY DON AND/OR PHIL UNLESS ALSO INCLUDES VOCAL OR OTHER SIGNIFICANT INPUT (the list would be too long!) BUT FOCUSES ON UNUSUAL OR RARE ASSOCIATIONS WITH OTHER ARTISTS & SPECIAL FILM TRACKS. OMITTED ARE THE VERY NUMEROUS TIMES THAT DON AND/OR PHIL 'DUETTED' THEIR HITS WITH OTHER ARTISTS UNLESS VERY SIGNIFICANT AND ISSUED ON RECORD OR IN SOME CASES VIDEO/DVD. ALL RECORDINGS LISTED ARE OR HAVE BEEN AVAILABLE AS OFFICIAL SNGLE, LP OR CD RELEASES OR AS BOOTLEGS. SHOWS RECORDING DATE (UK STYLE), MASTER NUMBER, FIRST 45 SINGLE, FIRST VINYL ALBUM (VA) & PRINCIPLE CD RELEASES. VINYL RECORD NUMBERS ARE ONES I KNOW OF, US OR UK. DATES, A CLOSE APROXIMATION TO RECORDING AND/OR RELEASE. WHERE POSSIBLE I HAVE INDICATED THE MOST RECENT AND/OR AVAILABLE CD. SOME ARE COMPILATIONS THAT INCLUDE TRACKS FROM EARLIER VINYL ALBUMS (VA) OR CDS. MANY RARE TRACKS NOW ALSO AVAILABLE AS DOWNLOADS. KEY: BLUE: DON; PURPLE: PHIL; GREEN: JOINT; C: COMPOSER(S); V: VOCAL; I: INSTRUMENTAL; P: PRODUCER(S) SCROLL DOWN TO SEE NOTES/ACKNOWELDGEMENTS. REC/REL. MASTER TRACK TITLE/ARTIST DON'S/PHIL'S ROLE 1st 78/45 rpm 1st VA CDs DATE No. (VINYLALBUM (VA)/CD TITLE - if applicable) No. No. ▼1954▼ 1954 THOU SHALT NOT STEAL/Kitty Wells C Decca 9-29313 (VA: KITTY WELLS; CD: THE COLLECTION Vocalion VL 73786 Spectrum 1132112 (a (very fine) re-recording) - and others) ▼1955▼ 1955 F2WW2218 HERE WE ARE AGAIN/Anita Carter C RCA 47-6228 (CD: APPALACHIAN ANGEL) Bear Fm. -

EVERLYPEDIA (Formerly the Everly Brothers Index – TEBI) Coordinated by Robin Dunn & Chrissie Van Varik

EVERLYPEDIA (formerly The Everly Brothers Index – TEBI) Coordinated by Robin Dunn & Chrissie van Varik EVERLYPEDIA PART 2 E to J Contact us re any omissions, corrections, amendments and/or additional information at: [email protected] E______________________________________________ EARL MAY SEED COMPANY - see: MAY SEED COMPANY, EARL and also KMA EASTWOOD, CLINT – Born 31st May 1930. There is a huge quantity of information about Clint Eastwood his life and career on numerous websites, books etc. We focus mainly on his connection to The Everly Brothers and in particular to Phil Everly plus brief overview of his career. American film actor, director, producer, composer and politician. Eastwood first came to prominence as a supporting cast member in the TV series Rawhide (1959–1965). He rose to fame for playing the Man with No Name in Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy of spaghetti westerns (A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More, and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly) during the 1960s, and as San Francisco Police Department Inspector Harry Callahan in the Dirty Harry films (Dirty Harry, Magnum Force, The Enforcer, Sudden Impact and The Dead Pool) during the 1970s and 1980s. These roles, along with several others in which he plays tough-talking no-nonsense police officers, have made him an enduring cultural icon of masculinity. Eastwood won Academy Awards for Best Director and Producer of the Best Picture, as well as receiving nominations for Best Actor, for his work in the films Unforgiven (1992) and Million Dollar Baby (2004). These films in particular, as well as others including Play Misty for Me (1971), The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), Pale Rider (1985), In the Line of Fire (1993), The Bridges of Madison County (1995) and Gran Torino (2008), have all received commercial success and critical acclaim.