Singer-Songwriter Jesse Winchester Here Friday

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RON SEXSMITH TILBAKE MED NYTT ALBUM "CAROUSEL ONE" Slippes Via Cooking Vinyl 30 Mars 2015

04-02-2015 13:00 CET RON SEXSMITH TILBAKE MED NYTT ALBUM "CAROUSEL ONE" Slippes via Cooking Vinyl 30 mars 2015 Den kanadiske singer-songwriteren Ron Sexsmith annonserer i dag sitt nye album, Carousel One, slippes mandag 30 mars 2015. Carousel On er produsert av Jim Scott og har en imponerende liste av studiomusikere, blant andre Bob Glaub (John Lennon), Jon Graboff (John Lee Hooker, Dr. John), Don Heffington (Bob Dylan) och John McGinty (Dixie Chicks). Carousel One har fått sitt navn fra bagasjebandet på Los Angeles flyplass der innkommende fly fra Toronto ruller rundt. I fjor fikk Ron Sexsmith for tredje gang ta imot en Juno Award (Canadas største musikkpris), denna gangen ”Best Adult Alternative Album” for plata Forever Endeavour. Om arbeidet med Carousel One sier Ron; “I didn’t realize until we were putting the songs together for Carousel One that this would be more outgoing, there's a lot more humour, I mean, there’s even a smiling picture on the cover, which I’ve never had before. I just hope it doesn’t scare the children.” Tracklist: 1. Sure As The Sky 2. Saint Bernard 3. Loving You 4. Before The Night Is Gone 5. Lucky Penny 6. Getaway Car 7. Nothing Feels The Same Anymore 8. Sun’s Coming Out 9. Lord Knows 10. All Our Tomorrows 11. No One 12. Can’t Get My Act Together 13. Tumbling Sky 14. Many Times Hi-res pressebilde HER FROM THE DESK OF HENRIK HAAGENSEN Promotion PLAYGROUND MUSIC NORWAY TEL: +47 458 11 727 MAIL: [email protected] REPRESENTING:4AD - BAD TASTE - CITY SLANG - DOMINO - DRAMATICO - EAGLE vision/Rock - EAR MUSIC/EDEL - EPITAPH/ANTI - FRONTIERS - GRANDMONO - KOBALT - MATADOR - NAIVE - NETTWERK - NINJA TUNE - ONE LITTLE INDIAN - RELAPSE - ROUGH TRADE - SECRETLY CANADIAN - SUBPOP - XL RECORDINGS Kontaktpersoner Magni Sørløkk Pressekontakt Promotion Manager [email protected] +4748092018. -

Carefully Pieced Together Around Feist

FEIST ‘Let It Die’ is very much a voice album in close up, “eye to eye and ear to ear”. Carefully pieced together around Feist’s seductive and jhai* voice, the album forms the missing link between ye old folk (storytelling), the Brill building era (the quest for the hook), doo-wop (melody and mood) and minimal modern pop arrangements. Like line drawings as opposed to detailed paintings, these songs leave you space to fill in the emotional blanks. Its lack of complication makes ‘Let It Die’ standout from much of today’s musical offerings; put simply, a beautiful slice of sonic escapism to illustrate and interrupt the little moments that together tell us stories. A history not lacking in variety, the Canadian born singer has accomplished much in her few tender years, so for those inquisitive journo types, here are the last few years in a nut shell… “My first proper gig was supporting the Ramones at an outdoor festival when my high school punk band won a battle of the bands contest. We played together for about 5 years. I moved to Toronto from Calgary to see a musical injuries doctor, after losing my voice on my first cross-Canadian tour when I was 19. Not knowing a soul in Toronto I spent 6 months in a dark basement apartment with a 4 track and having been told not to sing I got a guitar to do it for me. A couple of years later I was playing guitar in By Divine Right and toured for 6 months opening for the Tragically Hip, mostly in front of stadium crowds of around 40,000. -

A Concert Review by Christof Graf

Leonard Cohen`s Tower Of Song: A Grand Gala Of Excellence Without Compromise by Christof Graf A Memorial Tribute To Leonard Cohen Bell Centre, Montreal/ Canada, 6th November 2017 A concert review by Christof Graf Photos by: Christof Graf “The Leonard Cohen Memorial Tribute ‘began in a grand fashion,” wrote the MONTREAL GAZETTE. “One Year After His Death, the Legendary Singer-Songwriter is Remembered, Spectacularly, in Montral,” headlined the US-Edition of NEWSWEEK. The media spoke of a “Star-studded Montreal memorial concert which celebrated life and work of Leonard Cohen.” –“Cohen fans sing, shout Halleluja in tribute to poet, songwriter Leonard,” was the title chosen by THE STAR. The NATIONAL POST said: “Sting and other stars shine in fast-paced, touching Leonard Cohen tribute in Montreal.” Everyone present shared this opinion. It was a moving and fascinating event of the highest quality. The first visitors had already begun their pilgrimage to the Hockey Arena of the Bell Centre at noon. The organizers reported around 20.000 visitors in the evening. Some media outlets estimated 16.000, others 22.000. Many visitors came dressed in dark suits and fedora hats, an homage to Cohen’s “work attire.” Cohen last sported his signature wardrobe during his over three hour long concerts from 2008 to 2013. How many visitors were really there was irrelevant; the Bell Centre was filled to the rim. The “Tower Of Song- A Memorial Tribute To Leonard Cohen” was sold out. Expectations were high as fans of the Canadian Singer/Songwriter pilgrimmed from all over the world to Montreal to pay tribute to their deceased idol. -

November/December 2005 Issue 277 Free Now in Our 31St Year

jazz &blues report november/december 2005 issue 277 free now in our 31st year www.jazz-blues.com Sam Cooke American Music Masters Series Rock & Roll Hall of Fame & Museum 31st Annual Holiday Gift Guide November/December 2005 • Issue 277 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum’s 10th Annual American Music Masters Series “A Change Is Gonna Come: Published by Martin Wahl The Life and Music of Sam Cooke” Communications Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Inductees Aretha Franklin Editor & Founder Bill Wahl and Elvis Costello Headline Main Tribute Concert Layout & Design Bill Wahl The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and sic for a socially conscientious cause. He recognized both the growing popularity of Operations Jim Martin Museum and Case Western Reserve University will celebrate the legacy of the early folk-rock balladeers and the Pilar Martin Sam Cooke during the Tenth Annual changing political climate in America, us- Contributors American Music Masters Series this ing his own popularity and marketing Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, November. Sam Cooke, considered by savvy to raise the conscience of his lis- Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, many to be the definitive soul singer and teners with such classics as “Chain Gang” Peanuts, Mark Smith, Duane crossover artist, a model for African- and “A Change is Gonna Come.” In point Verh and Ron Weinstock. American entrepreneurship and one of of fact, the use of “A Change is Gonna Distribution Jason Devine the first performers to use music as a Come” was granted to the Southern Chris- tian Leadership Conference for ICON Distribution tool for social change, was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in the fundraising by Cooke and his manager, Check out our new, updated web inaugural class of 1986. -

Approximately 286 Reasons Why You Should Listen to Jesse Winchester

December 1974 Approximately 286 reasons why you should listen to Jesse Winchester By Giovanni Daddomo If you’ve been a reader of Zigzag for as long as I have, i.e., since very early on, you’ll recall how at the start there weren’t too many interviews, most of the features being of the type now more often found in the younger fan magazines such as Fat Angel, Omaha Rainbow, Hot Wacks et al, that is, extended eulogies of a band/singer garnished with whatever biographical information the authors were/are able to glean from their subjects’ press offices. I’d like to revert to that praiseworthy (if wanting) form in the case of Jesse Winchester because (a) I doubt if enough people are familiar enough with Jesse’s work for an extended interview to be warranted at this time, and (b) because he wasn’t in when I phoned him. Anyway, that’s the waffle taken care of, so let’s progress without further ado to…. The Skimpy Biography Jesse was born in Shreveport, Louisiana in 1945. He was a musical infant, playing piano by the time he was six and organ in the local church by the time he was twelve. In 1959 Jesse discovered rock’n’roll, got himself a cheap guitar and joined a group on the strength of the three chords he learned the same day he bought the guitar. His heroes at this time were Ray Charles and Jerry Lee Lewis. Jesse played the local clubs, bars, dancehalls and college circuits with various bands and eventually (1967) ended up in Hamburg with a now forgotten band. -

88-Page Mega Version 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010

The Gift Guide YEAR-LONG, ALL OCCCASION GIFT IDEAS! 88-PAGE MEGA VERSION 2017 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010 COMBINED jazz & blues report jazz-blues.com The Gift Guide YEAR-LONG, ALL OCCCASION GIFT IDEAS! INDEX 2017 Gift Guide •••••• 3 2016 Gift Guide •••••• 9 2015 Gift Guide •••••• 25 2014 Gift Guide •••••• 44 2013 Gift Guide •••••• 54 2012 Gift Guide •••••• 60 2011 Gift Guide •••••• 68 2010 Gift Guide •••••• 83 jazz &blues report jazz & blues report jazz-blues.com 2017 Gift Guide While our annual Gift Guide appears every year at this time, the gift ideas covered are in no way just to be thought of as holiday gifts only. Obviously, these items would be a good gift idea for any occasion year-round, as well as a gift for yourself! We do not include many, if any at all, single CDs in the guide. Most everything contained will be multiple CD sets, DVDs, CD/DVD sets, books and the like. Of course, you can always look though our back issues to see what came out in 2017 (and prior years), but none of us would want to attempt to decide which CDs would be a fitting ad- dition to this guide. As with 2016, the year 2017 was a bit on the lean side as far as reviews go of box sets, books and DVDs - it appears tht the days of mass quantities of boxed sets are over - but we do have some to check out. These are in no particular order in terms of importance or release dates. -

RAR Newsletter 130220.Indd

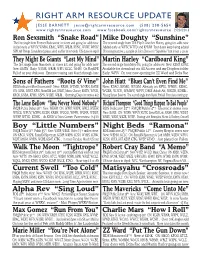

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 2/20/2013 Ron Sexsmith “Snake Road” Mike Doughty “Sunshine” The first single from Forever Endeavour, in stores and going for adds now The second single from The Flip Is Another Honey, going for adds now Added early at WFUV, WNRN, KBAC, WFIV, WBJB, KUNC, WUKY, WHRV Added early at WFIV, WTYD and KHUM Tour dates keep being added NPR All Things Considered piece aired earlier this month US dates in April This song features a sample of John Denver’s “Sunshine” but is not a cover They Might Be Giants “Lost My Mind” Martin Harley “Cardboard King” The first single from Nanobots, in stores 3/5 and going for adds now The second single from Mojo Fix, going for adds now New: KSMT, KUNC New: KMTN Early: WYMS, WBJB, WFIV, KCLC, WHRV On PlayMPE Available for download via All Access and my Dropbox folder Full cd on your desk soon Extensive touring runs March through June Early: WFIV On tour now opening for ZZ Ward and Delta Rae Sons of Fathers “Roots & Vine” John Hiatt “Blues Can’t Even Find Me” BDS Indicator Most Increased! New: KRSH, WTMD, WNRN, KAXE New: KTAO, KFMG, WUSM Already on: KPIG, WNKU, KBAC, ON: KINK, WEXT, KPIG, SiriusXM Loft, KSMT, Music Choice, KMTN, WYCE, WCBE, WJCU, WMWV, WFIV, DMX Adult Alt, WKZE, KDBB... KROK, KNBA, KFMU, KSPN, WCBE, WBJB... Burning Days in stores 4/2 Playing Sunset Sessions The second single from Mystic Pinball Tour dates coming up The Lone Bellow “You Never Need Nobody” Richard Thompson “Good Things Happen To Bad People” FMQB Public Debut 46*! New: WEHM ON: WXRT, WXPK, WRLT, WZEW, BDS Indicator 25*! FMQB Public 4*! Electric in stores now WNCS, WFUV, WXPN, KCSN, KRSH, WCOO, WFPK, WCNR, WDST, New: KAXE ON: WXPN, WFUV, KUTX, SiriusXM Loft, KRSH, KPIG, WDST, WYEP, WTYD, KDHX.. -

SINGER-SONGWRITER RON SEXSMITH at Whistling Gardens

For Immediate Release SINGER-SONGWRITER RON SEXSMITH at Whistling Gardens Amphitheatre Presented by The Waterford Old Town Hall “2nd Annual Off-site Concert June 24, 2017 - An Artistic Match Made In Juno Award Winning Heaven” (Wilsonville, Norfolk County Ontario Canada – May 23, 2017) After presenting Sarah Harmer to a sold out crowd in the stunning Whistling Gardens (WG) Amphitheatre in July 2016, The Waterford Old Town Hall (OTH) is delighted to present internationally acclaimed singer- songwriter and three-time Juno award winner RON SEXSMITH June 24, 2017. “We have struck creative gold with this partnership,” says Wanda Heimbecker, Co-owner of WG. “After the brilliant success we had working with the production team at the OTH to bring Sarah Harmer to our garden amphitheatre last summer, we instantly realized the peak potential of our annual collaboration, which mirrors the caliber and diversification of other iconic Canadian botanical gardens.” Canadian Folk/ Pop Icon Ron Sexsmith released his new album, The Last Rider April 21, 2017, immediately followed by a live tour. This, Ron’s thirteenth studio recording was co-produced at The Bathouse Studios in Kingston, Ontario by longtime drummer and collaborator Don Kerr and Sexsmith. The album is his first self-produced album and the first to include Ron’s touring band which will appear with him onstage at WG. “At this point, it’s just second nature for me to write short, melodic songs that say everything I want to say,” muses Sexsmith. “But having my band totally involved on this album maybe brought out more in the songs than on other recent albums. -

ADAM HAY – BIO and TESTIMONIALS

ADAM HAY – BIO and TESTIMONIALS "Adam Hay is awesome! PASSION and KNOWLEDGE! If I could take lessons from him I would." Paul Bostaph (SLAYER) Born in 1976, Adam Hay is a freelance drummer/drum teacher living in Canada, having played well over 2,000 dates since the early 1990s all over the US and Canada with Quintuple Platinum selling artist Chantal Kreviazuk (Sony/2x Juno Winner/3x Nominee), multiple Diamond (million) selling artistRaine Maida (Sony/Our Lady Peace/4x Juno Winner), Sarah Slean (Warner/Juno Nominee), Justin Rutledge (Six Shooter, Juno Nominee), Martina Sorbara (Mercury/Dragonette, Juno Nominee and Winner), Royal Wood (Dead Daisy/Six Shooter/ Juno Nominee), Patricia O'Callaghan (EMI), John Barrowman (Sony UK), Sharon Cuneta (Sony Philippines), KC Concepcion (Sony Philippines), Jeff Healey (George Harrison/multiple award winner), Dr. Draw, Luisito Orbegoso (Montreal Jazzfest Grand Prix winner), Cindy Gomez, George Koeller (Peter Gabriel/Bruce Cockburn/Dizzy Gillespie), Alexis Baro (David Foster/Paul Schaffer/Tom Jones/Cubanismo) Lesley Barber (composer for Film/TV/’Manchester by the Sea’), Jay Danley (award winner), Sonia Lee (first violinist with Toronto Symphony Orchestra for 6 years/Detroit Symphony Orchestra), Kevin Fox (Celine Dion, Justin Bieber), The Mercenaries, MOKOMOKAI, Leahy, Eric Schenkman (The Spin Doctors) and hundreds more. He has also recorded with producer David Bottrill (Peter Gabriel, Tool, Smashing Pumpkins, Rush). Adam has appeared live on national TV in front of millions of people (MTV, CTV's Canada AM, City TV's Breakfast Television, CBC, Rogers TV, Mike Bullard on CTV) and live radio shows, award ceremonies, TV and Radio commercials as a jingle artist, sold out theaters and festivals, music videos, national TV Season launch parties, many full length albums, record company showcases in the USA and Canada, minuscule cafeterias, to downtown sidewalks as a busker earlier on. -

25995 Yamaha

Ray Charles isn’t just a giant of American music. He is American music. ASASinGer , SonGwriTer , keYboArDiST , AnD bAnDleADer , C hArleS has left an indelible stamp on rock, r&b, blues, jazz, and country, often by single-handedly redefining the boundaries between them. born in Albany, Georgia, in 1930, Charles studied music at a florida school for the blind before settling in Seattle in 1947. A MASTERS VOICE There he developed a jazzy style in the mode of nat king Cole. Conversations with Ray Charles he also worked as an arranger, most notably on Guitar Slim’s 1953 classic “The Things That i used to Do,” easily one of the most important blues tracks of all time. but Charles really hit his stride with 1955’s “i’ve Got a woman,” whose raucous, gospel-inflected style was a bold departure from his earlier, smoother style. follow-up hits such as “what’d i Say” and “hallelujah i love her So” cemented Charles’s position as r&b’s most important stylist. James brown is the Godfather of Soul; ray Charles is simply the father. in the early ’60s, Charles launched a second musical revolution: he demolished the wall between r&b and country music with such hits as “i Can’t Stop loving You” and “You Don’t know Me.” Charles is still going strong 50 years after “The Things That i used to Do,” thrilling audiences with one of the world’s most recognizable and beloved voices. he also strives to improve the lives of hearing-impaired children through the ray Charles foundation. -

1 Miles Davis Quintet, Live in Europe 1967: the Bootleg Series, Vol. 1

77TH ANNUAL READERS POLL HISTORICAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR 1 Miles Davis Quintet, Live In Europe 1967: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 1 (COLUMBIA/LEGACY) 2,619 votes The trumpeter and his second great quintet were in their prime while touring with George Wein’s Newport Jazz Festival in October and November 1967. 2 Wes Montgomery, Echoes 5 Stan Getz, Stan Getz 8 Fela Kuti, Vinyl Box Set I Of Indiana Avenue Quintets: The Clef & (KNITTING FACTORY/ (RESONANCE) 1,270 Norgran Studio Albums LABEL MAISON) 465 (HIP-O SELECT) 642 Newly dis- This package of covered live This three-disc remastered Fela recordings made collection, which Kuti albums—the in Indianapolis concentrates on first in a series sometime in Getz’s earliest sin- of vinyl box sets 1957 or ’58 gles and albums covering the shed light on the early work of (1952–1955) for work of the world-renown Afro- one of jazz’s greatest guitarists Norman Granz, elegantly fills a gap beat vocalist—was curated by during a pivotal point in his career. in the saxophonist’s discography. Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson. 3 The Dave Brubeck Quartet, 6 The Dave Brubeck Quartet, 9 Howlin’ Wolf, Smokestack The Columbia Studio Their Last Time Out Lightning:The Complete Albums Collection: 1955– (COLUMBIA/LEGACY) 596 Chess Masters, 1951–1960 (HIP-O SELECT/GEFFEN) 464 1966 (COLUMBIA/LEGACY) 1,001 Brubeck’s quar- tet of 17 years Perhaps the most Containing about with Paul Des- unique and power- 12 hours of mond, Eugene ful performer in music, this box Wright and Joe the history of the set covers all 19 Morello played blues, How- studio albums their last concert lin’ Wolf cre- that Brubeck together in Pittsburgh on Dec. -

BOBBY CHARLES LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie Van Varik

BOBBY CHARLES LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie van Varik. Bobby Charles was born Robert Charles Guidry on 21st February 1938 in Abbeville, Louisiana. A native Cajun himself, he recalled that his life “changed for ever” when he re-tuned his parents’ radio set from a local Cajun station to one playing records by Fats Domino. Most successful as a songwriter, he is regarded as one of the founding fathers of swamp pop. His own vocal style was laidback and drawling. His biggest successes were songs other artists covered, such as ‘See You Later Alligator’ by Bill Haley & His Comets; ‘Walking To New Orleans’ by Fats Domino - with whom he recorded a duet of the same song in the 1990s - and ‘(I Don’t Know Why) But I Do’ by Clarence “Frogman” Henry. It allowed him to live off the song-writing royalties for the rest of his life! No albums were by him released in this period. Two other well-known compositions are ‘The Jealous Kind’, recorded by Joe Cocker, and ‘Tennessee Blues’ by Kris. Disenchanted with the music business, Bobby disappeared from the music scene in the mid-1960s but returned in 1972 with a self-titled album on the Bearsville label on which he was accompanied by Rick Danko and several other members of the Band and Dr John. Bobby later made a rare live appearance as a guest singer on stage at The Last Waltz, the 1976 farewell concert of the Band, although his contribution was cut from Martin Scorsese’s film of the event. Bobby Charles returned to the studio in later years, recording a European-only album called Clean Water in 1987.