Alternative Fuel Vehicle Acrobat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Gas Vehicles Myth Vs. Reality

INNOVATION | NGV NATURAL GAS VEHICLES MYTH VS. REALITY Transitioning your fleet to alternative fuels is a major decision, and there are several factors to consider. Unfortunately, not all of the information in the market related to heavy-duty natural gas vehicles (NGVs) is 100 percent accurate. The information below aims to dispel some of these myths while providing valuable insights about NGVs. MYTH REALITY When specifying a vehicle, it’s important to select engine power that matches the given load and duty cycle. Earlier 8.9 liter natural gas engines were limited to 320 horsepower. They were not always used in their ideal applications and often pulled loads that were heavier than intended. As a result, there were some early reliability challenges. NGVs don’t have Fortunately, reliability has improved and the Cummins Westport near-zero 11.9 liter engine enough power, offers up to 400 horsepower and 1,450 lb-ft torque to pull full 80,000 pound GVWR aren’t reliable. loads.1 In a study conducted by the American Gas Association (AGA) NGVs were found to be as safe or safer than vehicles powered by liquid fuels. NGVs require Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) fuel tanks, or “cylinders.” They need to be inspected every three years or 36,000 miles. The AGA study goes on to state that the NGV fleet vehicle injury rate was 37 CNG is not safe. percent lower than the gasoline fleet vehicle rate and there were no fuel related fatalities compared with 1.28 deaths per 100 million miles for gasoline fleet vehicles.2 Improvements in CNG cylinder storage design have led to fuel systems that provide E F range that matches the range of a typical diesel-powered truck. -

Electric Vehicles Electric Vehicle Expansion Liquefied Natural Gas

The Road to 1 Billion Miles in UPS’s Alternative Fuel and Advanced Technology Vehicles UPS is committed to better fuel alternatives, now and for the future. That’s why we recently announced a new goal –– to drive 1 billion miles in our alternative fuel and advanced technology vehicles by 2017. With nearly 3,000 vehicles currently in our “rolling laboratory,” we’re creating sustainable connections and delivering innovative, new technologies on the road and around the globe. 1 000 000 00 0 miles by 2017 1 Billion Miles Our goal is to drive 1 billion miles in alternative fuel and advanced technology vehicles by the end of 2017 — more than double our previous goal to drive 400 million miles. 295 Million Miles 212 Million Miles Base Year 100 Million Miles 2000 2005 2010 2012 2017 Electric Vehicle Liquefied Natural Gas Expansion Announcement x20 100x 2013 2013 Earlier this year we deployed 100 fully electric UPS announced the purchase of 700 LNG tractors in commercial vehicles throughout California. These 2013 and plan to ultimately have more than 1,000 in additions to our electric vehicle fleet will help our fleet. These tractors will operate from LNG fueling offset the consumption of conventional motor fuel stations in Las Vegas, Nev.; Phoenix, Ariz., and Beaver by an estimated 126,000 gallons per year. and Salt Lake City, Utah among other locations. Electric Vehicles Diesel Hybrid Hydraulic 2001 First tested in New York City in the 1930s, we 2006 took a second look in Santiago, Chile, in 2001. Harnessing hydraulic power sharply increases fuel Today, we have more than 100 worldwide. -

Morgan Ellis Climate Policy Analyst and Clean Cities Coordinator DNREC [email protected] 302.739.9053

CLEAN TRANSPORTATION IN DELAWARE WILMAPCO’S OUR TOWN CONFERENCE THE PRESENTATION 1) What are alterative fuels? 2) The Fuels 3) What’s Delaware Doing? WHAT ARE ALTERNATIVE FUELED VEHICLES? • “Vehicles that run on a fuel other than traditional petroleum fuels (i.e. gas and diesel)” • Propane • Natural Gas • Electricity • Biodiesel • Ethanol • Hydrogen THERE’S A FUEL FOR EVERY FLEET! DELAWARE’S ALTERNATIVE FUELS • “Vehicles that run on a fuel other than traditional petroleum fuels (i.e. gas and diesel)” • Propane • Natural Gas • Electricity • Biodiesel • Ethanol • Hydrogen THE FUELS PROPANE • By-Product of Natural Gas • Compressed at high pressure to liquefy • Domestic Fuel Source • Great for: • School Busses • Step Vans • Larger Vans • Mid-Sized Vehicles COMPRESSED NATURAL GAS (CNG) • Predominately Methane • Uses existing pipeline distribution system to deliver gas • Good for: • Heavy-Duty Trucks • Passenger cars • School Buses • Waste Management Trucks • DNREC trucks PROPANE AND CNG INFRASTRUCTURE • 8 Propane Autogas Stations • 1 CNG Station • Fleet and Public Access with accounts ELECTRIC VEHICLES • Electricity is considered an alternative fuel • Uses electricity from a power source and stores it in batteries • Two types: • Battery Electric • Plug-in Hybrid • Great for: • Passenger Vehicles EV INFRASTRUCTURE • 61 charging stations in Delaware • At 26 locations • 37,000 Charging Stations in the United States • Three types: • Level 1 • Level 2 • D.C. Fast Charging TYPES OF CHARGING STATIONS Charger Current Type Voltage (V) Charging Primary Use Time Level 1 Alternating 120 V 2 to 5 miles Current (AC) per hour of Residential charge Level 2 AC 240 V 10 to 20 miles Residential per hour of and charge Commercial DC Fast Direct Current 480 V 60 to 80 miles (DC) per 20 min. -

CASE Studies

THE STATE OF ASIAN CITIES 2010/11 CASE STUDIES TRANSPORTATION POSITIVE CHANGE IS WITHIN REACH Transportation generates at least one third of greenhouse gas emissions in urban areas, but positive change is within reach, and much more easily than some policymakers might think. Cycle rickshaws remain a policy blind spot The cycle rickshaw remains widely popular in Asian cities and is a sustainable urban transport for short- distance trips (1-5 km). It can also complement and integrate very effectively as a low-cost feeder service to public transport systems, providing point-to-point service (i.e., from home to a bus stop). According to estimates, over seven million passenger/goods cycle rickshaws are in operation in various Indian cities (including some 600,000 in India’s National Capital Region) where they are used by substantial numbers of low- and middle-income commuters as well as tourists, and even goods or materials. Still, for all its popularity and benefits, this non-polluting type of transport is largely ignored by policymakers and transport planners. Recently in Delhi, a ban on cycle rickshaws resulted in additional traffic problems as people turned to ‘auto’ (i.e., motorized) rickshaws instead. The ban met with public outcry and opposition from many civil society groups. In a landmark decision in February 2010, the Delhi High Court ruled that the Municipal Corporation’s ban on cycle rickshaws was unconstitutional. State of Asian Cities Report 2010/11, Ch. 4, Box 4.17 Delhi’s conversion to natural gas and solar power In 1998 and at the request of India’s non-governmental Centre for Science and Environment, the country’s Supreme Court directed the Delhi Government to convert all public transport and para-transit vehicles from diesel or petrol engines to compressed natural gas (CNG). -

Fuel Properties Comparison

Alternative Fuels Data Center Fuel Properties Comparison Compressed Liquefied Low Sulfur Gasoline/E10 Biodiesel Propane (LPG) Natural Gas Natural Gas Ethanol/E100 Methanol Hydrogen Electricity Diesel (CNG) (LNG) Chemical C4 to C12 and C8 to C25 Methyl esters of C3H8 (majority) CH4 (majority), CH4 same as CNG CH3CH2OH CH3OH H2 N/A Structure [1] Ethanol ≤ to C12 to C22 fatty acids and C4H10 C2H6 and inert with inert gasses 10% (minority) gases <0.5% (a) Fuel Material Crude Oil Crude Oil Fats and oils from A by-product of Underground Underground Corn, grains, or Natural gas, coal, Natural gas, Natural gas, coal, (feedstocks) sources such as petroleum reserves and reserves and agricultural waste or woody biomass methanol, and nuclear, wind, soybeans, waste refining or renewable renewable (cellulose) electrolysis of hydro, solar, and cooking oil, animal natural gas biogas biogas water small percentages fats, and rapeseed processing of geothermal and biomass Gasoline or 1 gal = 1.00 1 gal = 1.12 B100 1 gal = 0.74 GGE 1 lb. = 0.18 GGE 1 lb. = 0.19 GGE 1 gal = 0.67 GGE 1 gal = 0.50 GGE 1 lb. = 0.45 1 kWh = 0.030 Diesel Gallon GGE GGE 1 gal = 1.05 GGE 1 gal = 0.66 DGE 1 lb. = 0.16 DGE 1 lb. = 0.17 DGE 1 gal = 0.59 DGE 1 gal = 0.45 DGE GGE GGE Equivalent 1 gal = 0.88 1 gal = 1.00 1 gal = 0.93 DGE 1 lb. = 0.40 1 kWh = 0.027 (GGE or DGE) DGE DGE B20 DGE DGE 1 gal = 1.11 GGE 1 kg = 1 GGE 1 gal = 0.99 DGE 1 kg = 0.9 DGE Energy 1 gallon of 1 gallon of 1 gallon of B100 1 gallon of 5.66 lb., or 5.37 lb. -

China at the Crossroads

SPECIAL REPORT China at the Crossroads Energy, Transportation, and the 21st Century James S. Cannon June 1998 INFORM, Inc. 120 Wall Street New York, NY 10005-4001 Tel (212) 361-2400 Fax (212) 361-2412 Site www.informinc.org Gina Goldstein, Editor Emily Robbins, Production Editor © 1998 by INFORM, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISSN# 1050-8953 Volume 5, Number 2 Acknowledgments INFORM is grateful to all those who contributed their time, knowledge, and perspectives to the preparation of this report. We also wish to thank ARIA Foundation, The Compton Foundation, The Overbrook Foundation, and The Helen Sperry Lea Foundation, without whose generous support this work would not have been possible. Table of Contents Preface Introduction: A Moment of Choice for China. ........................................................................1 Motor Vehicles in China: Oil and Other Options...................................................................3 Motor Vehicle Manufacturing........................................................................................................3 Oil: Supply and Demand...............................................................................................................5 Alternative Vehicles and Fuels........................................................................................................8 Natural Gas Vehicles.....................................................................................................8 Liquefied Petroleum Gas ..............................................................................................10 -

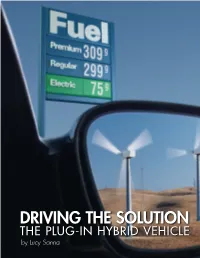

EPRI Journal--Driving the Solution: the Plug-In Hybrid Vehicle

DRIVING THE SOLUTION THE PLUG-IN HYBRID VEHICLE by Lucy Sanna The Story in Brief As automakers gear up to satisfy a growing market for fuel-efficient hybrid electric vehicles, the next- generation hybrid is already cruis- ing city streets, and it can literally run on empty. The plug-in hybrid charges directly from the electricity grid, but unlike its electric vehicle brethren, it sports a liquid fuel tank for unlimited driving range. The technology is here, the electricity infrastructure is in place, and the plug-in hybrid offers a key to replacing foreign oil with domestic resources for energy indepen- dence, reduced CO2 emissions, and lower fuel costs. DRIVING THE SOLUTION THE PLUG-IN HYBRID VEHICLE by Lucy Sanna n November 2005, the first few proto vide a variety of battery options tailored 2004, more than half of which came from Itype plugin hybrid electric vehicles to specific applications—vehicles that can imports. (PHEVs) will roll onto the streets of New run 20, 30, or even more electric miles.” With growing global demand, particu York City, Kansas City, and Los Angeles Until recently, however, even those larly from China and India, the price of a to demonstrate plugin hybrid technology automakers engaged in conventional barrel of oil is climbing at an unprece in varied environments. Like hybrid vehi hybrid technology have been reluctant to dented rate. The added cost and vulnera cles on the market today, the plugin embrace the PHEV, despite growing rec bility of relying on a strategic energy hybrid uses battery power to supplement ognition of the vehicle’s potential. -

Leak Detection in Natural Gas and Propane Commercial Motor Vehicles Course

Leak Detection in Natural Gas and Propane Commercial Motor Vehicles Course July 2015 Table of Contents 1. Leak Detection in Natural Gas and Propane Commercial Motor Vehicles Course ............................................... 1 1.1 Introduction and Overview ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Welcome ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.3 Course Goal .................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.4 Training Outcomes ......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.5 Training Outcomes (Continued) ..................................................................................................................... 2 1.6 Course Objectives .......................................................................................................................................... 2 1.7 Course Topic Areas ........................................................................................................................................ 2 1.8 Course Overview ............................................................................................................................................ 2 1.9 Module One: Overview of CNG, LNG, -

Gasoline-Electric Hybrid Synergy Drive

Gasoline-Electric Hybrid Synergy Drive AHV40 Series Foreword In March 2006, Toyota released the Toyota CAMRY gasoline-electric hybrid vehicle in North America. Except where noted in this guide, basic vehicle systems and features for the CAMRY hybrid are the same as those on the conventional, non-hybrid, Toyota CAMRY. To educate and assist emergency responders in the safe handling of the CAMRY hybrid technology, Toyota published this CAMRY hybrid Emergency Response Guide. High voltage electricity powers the electric motor, generator, A/C compressor, and inverter/converter. All other automotive electrical devices such as the headlights, power steering, horn, radio, and gauges are powered from a separate 12 Volts battery. Numerous safeguards have been designed into the CAMRY to help ensure the high voltage, approximately 245 Volts, Nickel Metal Hydride (NiMH) Hybrid Vehicle (HV) battery pack is kept safe and secure in an accident. Additional topics contained in the guide include: N Toyota CAMRY identification. N Major hybrid component locations and descriptions. By following the information in this guide, dismantlers will be able to handle the CAMRY hybrid-electric vehicle as safely as the dismantling of a conventional gasoline engine automobile. ¤ 2006 Toyota Motor Corporation All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced or copied, in whole or in part, without the written permission of Toyota Motor Corporation ii Table of Contents About the CAMRY.........................................................................................................................1 -

2002-00201-01-E.Pdf (Pdf)

report no. 2/95 alternative fuels in the automotive market Prepared for the CONCAWE Automotive Emissions Management Group by its Technical Coordinator, R.C. Hutcheson Reproduction permitted with due acknowledgement Ó CONCAWE Brussels October 1995 I report no. 2/95 ABSTRACT A review of the advantages and disadvantages of alternative fuels for road transport has been conducted. Based on numerous literature sources and in-house data, CONCAWE concludes that: · Alternatives to conventional automotive transport fuels are unlikely to make a significant impact in the foreseeable future for either economic or environmental reasons. · Gaseous fuels have some advantages and some growth can be expected. More specifically, compressed natural gas (CNG) and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) may be employed as an alternative to diesel fuel in urban fleet applications. · Bio-fuels remain marginal products and their use can only be justified if societal and/or agricultural policy outweigh market forces. · Methanol has a number of disadvantages in terms of its acute toxicity and the emissions of “air toxics”, notably formaldehyde. In addition, recent estimates suggest that methanol will remain uneconomic when compared with conventional fuels. KEYWORDS Gasoline, diesel fuel, natural gas, liquefied petroleum gas, CNG, LNG, Methanol, LPG, bio-fuels, ethanol, rape seed methyl ester, RSME, carbon dioxide, CO2, emissions. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This literature review is fully referenced (see Section 12). However, CONCAWE is grateful to the following for their permission to quote in detail from their publications: · SAE Paper No. 932778 ã1993 - reprinted with permission from the Society of Automotive Engineers, Inc. (15) · “Road vehicles - Efficiency and emissions” - Dr. Walter Ospelt, AVL LIST GmbH. -

General Tax Information Bulletin #300 Page 2

INFORMATION BULLETIN #300 GENERAL TAX JUNE 2021 (Replaces Bulletin #300 dated June 2020) Effective Date: July 1, 2021 SUBJECT: Sales of Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) and Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) REFERENCES: IC 6-2.5-5-51; IC 6-6-2.5-1; IC 6-6-2.5-16.5; IC 6-6-2.5-22; IC 6-6-2.5- 22.5; IC 6-6-2.5-28; IC 6-6-4.1-1; IC 6-6-4.1-4; IC 6-6-4.1-4.5. DISCLAIMER: Commissioner’s directives are intended to provide nontechnical assistance to the general public. Every attempt is made to provide information that is consistent with the appropriate statutes, rules, and court decisions. Any information that is not consistent with the law, regulations, or court decisions is not binding on either the department or the taxpayer. Therefore, the information provided herein should serve only as a foundation for further investigation and study of the current law and procedures related to the subject matter covered herein. SUMMARY OF CHANGES The bulletin was updated to provide the new special fuel tax rate effective July 1, 2021. I. DEFINITIONS “Natural gas” means compressed or liquid natural gas. “Natural gas product” means: (1) A liquid natural gas (LNG) or compressed natural gas (CNG) product; or (2) A combination of liquefied petroleum gas and a compressed natural gas product; used in an internal combustion engine or a motor to propel any form of vehicle, machine, or mechanical contrivance. “Alternative fuel” means a liquefied petroleum gas, not including a biodiesel fuel or biodiesel blend, used in an internal combustion engine or a motor to propel any form of vehicle, machine, or mechanical contrivance. -

Electric Vehicles: a Primer on Technology and Selected Policy Issues

Electric Vehicles: A Primer on Technology and Selected Policy Issues February 14, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46231 SUMMARY R46231 Electric Vehicles: A Primer on Technology and February 14, 2020 Selected Policy Issues Melissa N. Diaz The market for electrified light-duty vehicles (also called passenger vehicles; including passenger Analyst in Energy Policy cars, pickup trucks, SUVs, and minivans) has grown since the 1990s. During this decade, the first contemporary hybrid-electric vehicle debuted on the global market, followed by the introduction of other types of electric vehicles (EVs). By 2018, electric vehicles made up 4.2% of the 16.9 million new light-duty vehicles sold in the United States that year. Meanwhile, charging infrastructure grew in response to rising electric vehicle ownership, increasing from 3,394 charging stations in 2011 to 78,301 in 2019. However, many locations have sparse or no public charging infrastructure. Electric motors and traction battery packs—most commonly made up of lithium-ion battery cells—set EVs apart from internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs). The battery pack provides power to the motor that drives the vehicle. At times, the motor acts as a generator, sending electricity back to the battery. The broad categories of EVs can be identified by whether they have an internal combustion engine (i.e., hybrid vehicles) and whether the battery pack can be charged by external electricity (i.e., plug-in electric vehicles). The numerous vehicle technologies further determine characteristics such as fuel economy rating, driving range, and greenhouse gas emissions. EVs can be separated into three broad categories: Hybrid-electric vehicles (HEVs): The internal combustion engine primarily powers the wheels.