Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waste Water Transformed Into Heat Energy Abstract 1. Introduction

Waste water transformed into heat energy Authors: Konstantinos Ninikas 1, Nicholas Hytiris 1, Rohinton Emmanuel 1, Bjorn Aaen 1, Paul L. Younger 2 1 Glasgow Caledonian University, UK. – 2 University of Glasgow, UK. Abstract This study investigates the feasibility of utilising ground water ingress into the Glasgow Subway system. At present this unused excess water is being discharged into the city’s drainage system as waste. This valuable resource could be channelled through a Water Source Heat Pump (WSHP) to produce heat energy for domestic or public use (heating and domestic hot water). A study has been carried out in order to calculate the heat contained in the water. Water flow and water temperature have been recorded over a ten month period (since May 2014) at fifteen different points within the network of underground tunnels. Water sampling has also been undertaken at all of these points, with chemical analysis results for six of them already obtained. The measurements will continue for at least seven more months to have readings for an 18 months period. A feasibility study to review the number of support factors (i.e. Renewable Heat Incentive) that could profit the subway system has been undertaken as well. Options have been discussed and a selection of a site inside the tunnels for a pilot system has been decided and is due to be installed in June 2015. The findings of this study are expected to develop an appropriate renewable solution through a cost effective heat pump system design. This waste water will be collected and used as renewable energy. -

Proposal for the Future of Bridgeton, Castlemilk and Maryhill Jobcentres

Response to the proposal for the future of Bridgeton, Castlemilk and Maryhill jobcentres Response to Consultation July 2017 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 Background ................................................................................................................ 1 DWP’s estates strategy ........................................................................................... 2 What does this mean for the City of Glasgow? ....................................................... 2 Consultation ................................................................................................................ 3 Management Summary .............................................................................................. 3 Summary of responses ............................................................................................... 3 Response themes ....................................................................................................... 4 Travel time .............................................................................................................. 4 Travel cost .............................................................................................................. 5 Access to services .................................................................................................. 6 Sanctions ............................................................................................................... -

Glasgow City Community Health Partnership Service Directory 2014 Content Page

Glasgow City Community Health Partnership Service Directory 2014 Content Page About the CHP 1 Glasgow City CHP Headquarters 2 North East Sector 3 North West Sector 4 South Sector 5 Adult Protection 6 Child Protection 6 Emergency and Out-of-Hours care 6 Addictions 7 - 9 Asylum Seekers 9 Breast Screening 9 Breastfeeding 9 Carers 10 - 12 Children and Families 13 - 14 Dental and Oral Health 15 Diabetes 16 Dietetics 17 Domestic Abuse / Violence 18 Employability 19 - 20 Equality 20 Healthy Living 21 Health Centres 22 - 23 Hospitals 24 - 25 Housing and Homelessness 26 - 27 Learning Disabilities 28 - 29 Mental Health 30 - 40 Money Advice 41 Nursing 41 Physiotherapy 42 Podiatry 42 Respiratory 42 Rehabilitation Services 43 Sexual Health 44 Rape and Sexual Assault 45 Stop Smoking 45 Transport 46 Volunteering 46 Young People 47-49 Public Partnership Forum 50 Comments and Complaints 51-21 About Glasgow City Community Health Partnership Glasgow City Community Health Partnership (GCCHP) was established in November 2010 and provides a wide range of community based health services delivered in homes, health centres, clinics and schools. These include health visiting, health improvement, district nursing, speech and language therapy, physiotherapy, podiatry, nutrition and dietetic services, mental health, addictions and learning disability services. As well as this, we host a range of specialist services including: Specialist Children’s Services, Homeless Services and The Sandyford. We are part of NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde and provide services for 584,000 people - the entire population living within the area defined by the LocalAuthority boundary of Glasgow City Council. Within our boundary, we have: 154 GP practices 136 dental practices 186 pharmacies 85 optometry practices (opticians) The CHP has more than 3,000 staff working for it and is split into three sectors which are aligned to local social work and community planning boundaries. -

Springburn House Care Home Service Adults 62 Broomfield Rd Glasgow G21 3UB Telephone: 0141 2761810

Springburn House Care Home Service Adults 62 Broomfield Rd Glasgow G21 3UB Telephone: 0141 2761810 Inspected by: Kathy Godfrey Marjorie Bain Type of inspection: Unannounced Inspection completed on: 31 October 2013 Inspection report continued Contents Page No Summary 3 1 About the service we inspected 6 2 How we inspected this service 7 3 The inspection 11 4 Other information 29 5 Summary of grades 30 6 Inspection and grading history 30 Service provided by: Glasgow City Council Service provider number: SP2003003390 Care service number: CS2003001040 Contact details for the inspector who inspected this service: Kathy Godfrey Telephone 0141 843 6840 Email [email protected] Springburn House, page 2 of 32 Inspection report continued Summary This report and grades represent our assessment of the quality of the areas of performance which were examined during this inspection. Grades for this care service may change after this inspection following other regulatory activity. For example, if we have to take enforcement action to make the service improve, or if we investigate and agree with a complaint someone makes about the service. We gave the service these grades Quality of Care and Support 4 Good Quality of Environment 4 Good Quality of Staffing 4 Good Quality of Management and Leadership 4 Good What the service does well Personal plans have good information including a detailed life history. There are detailed routines for getting up in the morning and personal care. Residents have lots of opportunities to participate in the home such as six monthly reviews of their service, residents meetings and questionnaires. They were encouraged to choose colours for a recent refurbishment. -

Glasgow City Health and Social Care Partnership Health Contacts

Glasgow City Health and Social Care Partnership Health Contacts January 2017 Contents Glasgow City Community Health and Care Centre page 1 North East Locality 2 North West Locality 3 South Locality 4 Adult Protection 5 Child Protection 5 Emergency and Out-of-Hours care 5 Addictions 6 Asylum Seekers 9 Breast Screening 9 Breastfeeding 9 Carers 10 Children and Families 12 Continence Services 15 Dental and Oral Health 16 Dementia 18 Diabetes 19 Dietetics 20 Domestic Abuse 21 Employability 22 Equality 23 Health Improvement 23 Health Centres 25 Hospitals 29 Housing and Homelessness 33 Learning Disabilities 36 Maternity - Family Nurse Partnership 38 Mental Health 39 Psychotherapy 47 NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Psychological Trauma Service 47 Money Advice 49 Nursing 50 Older People 52 Occupational Therapy 52 Physiotherapy 53 Podiatry 54 Rehabilitation Services 54 Respiratory Team 55 Sexual Health 56 Rape and Sexual Assault 56 Stop Smoking 57 Volunteering 57 Young People 58 Public Partnership Forum 60 Comments and Complaints 61 Glasgow City Community Health & Care Partnership Glasgow Health and Social Care Partnership (GCHSCP), Commonwealth House, 32 Albion St, Glasgow G1 1LH. Tel: 0141 287 0499 The Management Team Chief Officer David Williams Chief Officer Finances and Resources Sharon Wearing Chief Officer Planning & Strategy & Chief Social Work Officer Susanne Miller Chief Officer Operations Alex MacKenzie Clincial Director Dr Richard Groden Nurse Director Mari Brannigan Lead Associate Medical Director (Mental Health Services) Dr Michael Smith -

Campus Travel Guide Final 08092016 PRINT READY

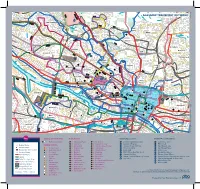

Lochfauld V Farm ersion 1.1 27 Forth and 44 Switchback Road Maryhill F C Road 6 Clyde Canal Road Balmore 1 0 GLASGOW TRANSPORT NETWORK 5 , 6 F 61 Acre0 A d Old Blairdardie oa R Drumchapel Summerston ch lo 20 til 23 High Knightswood B irkin e K F 6 a /6A r s de F 15 n R F 8 o Netherton a High d 39 43 Dawsholm 31 Possil Forth and Clyde Canal Milton Cadder Temple Gilshochill a 38 Maryhill 4 / 4 n F e d a s d /4 r a 4 a o F e River Lambhill R B d Kelvin F a Anniesland o 18 F 9 0 R 6 n /6A 1 40 r 6 u F M 30 a b g Springburn ry n h 20 i ill r R Ruchill p Kelvindale S Scotstounhill o a Balornock 41 d Possil G Jordanhill re Park C at 19 15 W es 14 te rn R 17 37 oa Old Balornock 2 d Forth and D um Kelvinside 16 Clyde b North art 11 Canal on Kelvin t Ro Firhill ad 36 ee 5 tr 1 42 Scotstoun Hamiltonhill S Cowlairs Hyndland 0 F F n e 9 Broomhill 6 F ac 0 r Maryhill Road V , a ic 6 S Pa tor Dowanhill d r ia a k D 0 F o S riv A 8 21 Petershill o e R uth 8 F 6 n F /6 G r A a u C 15 rs b R g c o u n Whiteinch a i b r 7 d e Partickhill F 4 p /4 S F a River Kelvin F 9 7 Hillhead 9 0 7 River 18 Craighall Road Port Sighthill Clyde Partick Woodside Forth and F 15 Dundas Clyde 7 Germiston 7 Woodlands Renfrew Road 10 Dob Canal F bie' 1 14 s Loa 16 n 5 River Kelvin 17 1 5 F H il 7 Pointhouse Road li 18 5 R n 1 o g 25A a t o Shieldhall F 77 Garnethill d M 15 n 1 14 M 21, 23 10 M 17 9 6 F 90 15 13 Alexandra Parade 12 0 26 Townhead 9 8 Linthouse 6 3 F Govan 33 16 29 Blyt3hswood New Town F 34, 34a Anderston © The University of Glasgo North Stobcross Street Cardonald -

Student / Living

1 STUDENT / LIVING 3 INVESTMENT CONSIDERATIONS • Prime student accommodation opportunity in • Commonwealth Games in Glasgow in 2014 core city centre location, fully let for 2013/14 will help bolster the city’s international reputation • Additional income from Sainsbury’s and Ask Restaurants • Potential to increase future income by continuing to move all student • 133 bedroom studio accommodation (140 accommodation contract lengths to 51 weeks beds), providing an average bedroom size of 27.14 sq m and excellent common facilities • Savills are instructed to seek offers in excess of £16,500,000 (sixteen million five • Highest specified scheme in Glasgow. The hundred thousand pounds) for the heritable property is a former lifestyle boutique hotel, title of the property, which reflects a net initial extensively refurbished and converted to yield of 6.40% on the student income, 6.00% student use in 2011 for the Sainsbury’s and 6.75% on the Ask unit, assuming purchaser’s costs of 5.80%. • Glasgow is a renowned and established The asset is for sale inclusive or exclusive of centre for higher education, boasting three the retail element. The SPV is also available main universities and a full time student to purchase and details can be provided on population of 50,450 request. • Excellent location within the heart of the city in close proximity to university campuses including Glasgow Caledonian and Strathclyde universities 4 S A R LOCATION A C E N S T A81 Glasgow is Scotland’s largest city and one of A879 the largest in the United Kingdom boasting G five recognised higher education institutions. -

Table: Names and Addresses for Glasgow Allotments the North Western Area

Table: Names and Addresses for Glasgow Allotments The North Western Area Balornock Allotments Beechwood Garscube Germiston Allotments Drumbottie Road Allotments Allotments,P Royston Road Balornock Beechwood Drive Maryhill Road Germiston G21 4JE G11 7EY Maryhill G21 2DJ Contact: Contact: beechwood- G20 0JU [email protected] balornockallotmentsassoci allotment- No contact details [email protected] [email protected] Website Hamiltonhill Kelvinside/julian Lambhill Allotments P Petershill Allotments P Allotments Avenue Allotments 11 Canal Bank North, Southloch Street Ellesmere Street 8 Cleveden Drive Lane G22 6RD Springburn G22 6SR G12 0RX Contact: admin@ G21 4AR Contact: Contact:kelvinside.allotme lambhillstables.org Contact: hamiltonhillallotment [email protected] Website petershilallotment@gmail. @googlemail.com Website facebook com facebook Trinley Brae Victoria Park Yoker Allotments Springburn Gardens P Allotments Allotments Yoker Linear Park Allotments Knightswood Road Northland Drive Greenlaw Road Springburn Road G13 2EY Scotstoun G14 0HF G21 1UX Contact: tbasecretary@ho G14 9HD Contact: Contact: offtheplot@btinte tmail.co.uk Contact: [email protected] rnet.com Website [email protected] o.uk facebook Website The North Eastern Area Budhill & Springboig Craigpark/ Dennistoun High Carntyne Kennyhill Community Allotments Allotments P Allotments Allotments Gartocher Road Craigpark Drive Duchray Street Dinart Street/Duchray Springboig Dennistoun G33 2DD Street Riddrie G32 0HE Contact: G31 2PD Contact: G33 [email protected] Contact: highcarntyneallotmentsa Contact: om [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Website k Website facebook facebook Shettleston Tollcross Park Wellhouse Allotments Westthorn Allotments P Community Growing Allotments P 1524 London Road (The Project Tollcross Park Wellhouse Crescent lane next to Celtic Club) Eckford Street Nr Muiryfauld Drive G33 4LA G31 4QA G32 7SA G31 5LN Contact: Contact: Contact: Contact: [email protected] [email protected]. -

New Stobhill Hospital the New Stobhill Ambulatory Care Hospital Belmont (ACH) Is Set in the Stobhill Campus

To Bishopbriggs FIF New Stobhill station E WAY New Stobhill Hospital The New Stobhill Ambulatory Care Hospital Belmont (ACH) is set in the Stobhill campus. The campus Hospital D Centre A O houses the hospital, a minor injuries unit, a R L L Marie Curie number of general and specialist mental health Walking and cycling guide 2021 HI Hospice Y facilities, and a brand new purpose-built Marie RA G Curie Cancer Care hospice. L BA A LORNOCK ROAD B The ACH provides outpatient clinics, day surgery and diagnostic services. There are hospital beds available to medics to extend the range of short B ALORNOCK ROAD stay surgical procedures offered to patients. B A L Skye House O At the main entrance there is a staffed help desk R N O and patient information points which provide C K R travel information, health promotion and other O A D advice. BELMONT ROAD Stobhill Hospital 2 new mental health wards are now on the campus. The two wards – Elgin and Appin – have space for up to 40 inpatients, with Elgin To Springburn dedicated to adult acute mental health inpatient station care and Appin focusing on older adults with functional mental health issues. Cycle Parking Entrance Rowanbank Bus stop Clinic BALORNOCK ROAD Active Travel Cycling to Work NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde recognise that New Stobhill Hospital is well served by public transport The Cycle to Work scheme is a salary sacrifice scheme physical activity is essential for good health covering bus travel within the immediate area and available to NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde staff*. -

Glasgow Life Venue Reopenings

GLASGOW LIFE VENUE REOPENINGS UPDATED WEDNESDAY 14 APRIL 2021 Glasgow Life expects to reopen the following venues. All information is based on Scottish Government guidance. It is indicative and subject to change. SERVICE AREA VENUE TO NOTE Anniesland Library Reopens on Tue 27 April Baillieston Library Reopens end August Currently open for PC access only Bridgeton Library Will reopen more fully on Tue 27 April Cardonald Library Reopens on Tue 27 April Castlemilk Library Reopens on Tue 27 April Dennistoun Library Reopens on Tue 27 April Currently open for PC access only Drumchapel Library Will reopen more fully on Tue 27 April LIBRARIES Currently open for PC access only Easterhouse Library Will reopen more fully on Tue 27 April Will reopen in 2022 due to ongoing Elder Park Library refurbishment Currently open for PC access only Gorbals Library Will reopen more fully on Tue 27 April Govanhill Library Reopens on Tue 27 April Hillhead Library Reopens on Fri 30 April Currently open for PC access only Ibrox Library Will reopen more fully on Tue 27 April Knightswood Library Reopens on Tue 27 April Langside Library Reopens end August Milton Library Reopens week of 14 June Parkhead Library Reopens end June Currently open for PC access only Partick Library Will reopen more fully on Tue 27 April Pollok Library Reopens week of 14 June Currently open for PC access only Pollokshaws Library Will reopen more fully on Tue 27 April LIBRARIES cont. Pollokshields Library Reopens end August Currently open for PC access only Possilpark Library Will reopen more -

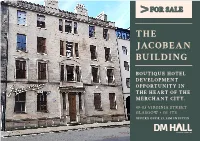

The Jacobean Building

FOR SALE THE JACOBEAN BUILDING BOUTIQUE HOTEL DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY IN THE HEART OF THE MERCHANT CITY. 49-53 VIRGINIA STREET GLASGOW • G1 1TS OFFERS OVER £1.33M INVITED THE JACOBEAN BUILDING This Grade A listed building dates back to as far as • Rare hotel development 1760 in the times of wealthy merchants in Glasgow opportunity. such as Speirs, Buchanan and Bowmen. Whilst in more recent times it has been used for traditional • Full planning consent commercial purposes these have included yoga granted. studios, offices and for a cookery school. • Within the chic The accommodation is arranged over basement, Merchant City. ground and three upper floors and benefits from a very attractive courtyard to the rear. Within • Offers over £1.33M its current ownership, the building has been invited for the freehold consistently maintained and upgraded since the interest. early 1990s. The main entrance is taken from Virginia Street. The property is on the fringe of the vibrant Merchant City area, with its diverse mix of retailing, pubs, restaurant and residential accommodation much of which has been developed over recent years to include flats for purchase and letting plus serviced apartments. DEVELOPER’S PLANNING PACK The subjects are Category A listed. Full planning permission has been granted for bar and restaurant Our client has provided us with an extensive uses for the ground and basement as well for 18 information pack on the history of the building boutique style hotel rooms to be developed above as well as the planning consents now in place. The on the upper floors. Full information and plans are following documents are available, available on Glasgow City Council’s Planning Portal with particular reference to application numbers - Package of the planning permissions 18/01725/FUL and 18/01726/LBA. -

7A Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

7A bus time schedule & line map 7A Westburn - Summerston via Rutherglen, Kings Park View In Website Mode and Glasgow City Centre The 7A bus line (Westburn - Summerston via Rutherglen, Kings Park and Glasgow City Centre) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Cambuslang: 6:30 PM (2) Glasgow: 6:48 AM - 10:29 PM (3) Rutherglen: 4:58 PM - 11:00 PM (4) Summerston: 6:27 AM - 5:07 PM (5) Westburn: 6:42 AM - 4:38 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 7A bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 7A bus arriving. Direction: Cambuslang 7A bus Time Schedule 6 stops Cambuslang Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 6:30 PM Dunlop Street, Westburn 205 Westburn Road, Glasgow Tuesday 6:30 PM Northbank Street, Westburn Wednesday 6:30 PM Newton Road, Westburn Thursday 6:30 PM Friday 6:30 PM Old Mill Road, Cambuslang Saturday Not Operational Kings Crescent, Cambuslang Christie Place, Cambuslang 7A bus Info Direction: Cambuslang Stops: 6 Trip Duration: 6 min Line Summary: Dunlop Street, Westburn, Northbank Street, Westburn, Newton Road, Westburn, Old Mill Road, Cambuslang, Kings Crescent, Cambuslang, Christie Place, Cambuslang Direction: Glasgow 7A bus Time Schedule 57 stops Glasgow Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 7:30 AM - 10:29 PM Monday 6:48 AM - 10:29 PM Dunlop Street, Westburn 205 Westburn Road, Glasgow Tuesday 6:48 AM - 10:29 PM Northbank Street, Westburn Wednesday 6:48 AM - 10:29 PM Newton Road, Westburn Thursday 6:48 AM - 10:29 PM Friday 6:48 AM - 10:29 PM Old Mill Road,